101 Meaningful Post Sixteen Special Education Activities for

Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties (IEPMLD)

Sensory AstroPhysics Session

Sensory AstroPhysics Session

This page is dedicated to detailing a range of meaningful activities for young people experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties in a post-school setting. While it is not claimed that every activity on this page will be suitable for all individuals, it is hoped that some may be tailored to the needs of someone in your care. Furthermore, while aiming to be comprehensive, it is not claimed that this page represents a full listings of all the meaningful activities possible for such a group of young people.

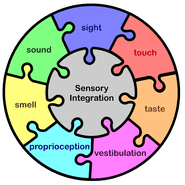

"Sensory cooking, sensory drama, sensory art, sensory garden, sensory room …. What does the word “sensory” written before the activity or place imply?" (Williams, 2010, page 23)

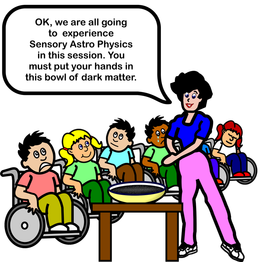

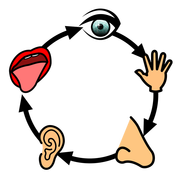

Not all activities are suitable for inclusion in any post-school curriculum on offer for Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties (hereafter the acronym IEPMLD will be used). As the cartoon suggests, simply placing the word 'sensory' in front of any activity does not, in and of itself, make it an appropriate curricula area; Sensory Russian (assuming the Learners are not Russian), Sensory Neurology, Sensory Welding, etc. are such examples. What then is appropriate and what right have others to decide what is or is not correct in this area of education? This page will attempt to address such issues.

Given that post school education for this group of young people is likely to be both short (one to three years) and expensive (running into tens of thousands of pounds), time should not be wasted on meaningless activities. The focus must be on things that will benefit individual future lives, enhance quality, and ensure a best transition route into a new adult world. This has been recognised for many years:

"Given the key characteristics of the students, what do they need to learn? In order to carry out this exercise successfully, you need to have a clear picture of what their lives are like now, and what they will be like in the future. What are the priorities? Remember that, although the students may have numerous gaps in their learning, you will only have them for two or three years. What are the things which will really

make a difference, even if they do not progress in the others?" (Griffiths & Tennyson, 1997, page 4)

Although specifically addressing schools, Richard Aird said the following in 2001:

"A pupil's school life is a brief affair, and the time in the classroom is a precious time that ought to be dedicated to minimising the handicapping affects of a pupil's disability and enabling the pupil to achieve maximum potential in a broad but relevant curriculum that is unique to the SLD sector and does not smack of the tokenism that has marred the history of the implementation of the National Curriculum in the SLD sector thus far." (Aird, 2001, page 14)

If school life is but a 'brief affair' then how many more constraints are placed on staff and student alike by an even shorter period of study in a post-school provision? Therefore, one might reasonably argue that there is an even greater need for this 'precious time' to have a specific focus as aptly indicated by Aird. Should this focus be different and distinct to that provided by an individual's school experience or should it be an allowance of further time (in some form of school extension) for Learners who, by definition, acquire knowledge at a very different rate to that of their peers?

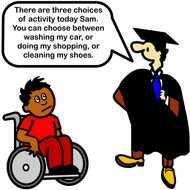

What do IEPMLD at this time in their lives really need to learn? Do they really need to be continuing placing their hands in mixtures of ingredients (for example) in some form of sensory cookery session as they have presumably been doing throughout their school career? How is this assisting a better quality of life in the future? There may well be a really good rationale for so doing. However, it must be made explicit and all staff (inclusive of the supporting team) must be made aware of this rationale. Indeed, one might ask if IEPMLD are ever likely to be cooking for themselves at all? In which case, why is cookery a part of your curriculum? It might be argued that 'cooking for leisure' is something that an IEPMLD might enjoy and thus choose to do for fun. This might be an acceptable rationale for the provision of this area on the curriculum but should it be compulsory for all Learners? Perhaps Learners should be permitted to choose what they wish to undertake acting as agents making decisions about their own future. Can IEPMLD act as agents? If this is believed not to be the case, does it not follow that one possible curriculum option would be the empowerment of young people through the development of 'agentive' awareness and skills? How can one choose if you do not know how to choose? How can you learn how to choose if you are never given choice? If you are never given choice how can you be an agent?

"One of the reasons that students with disabilities have not succeeded once they leave school is that the educational process has not prepared students with special learning needs adequately to become self-determined young people."

(Wehmeyer & Schalock, 2001, page 2)

For activities to be appropriate for Individuals Experiencing PMLD at F.E. level they must fulfill most of the following criteria. They must show how they:

• are age appropriate within the confines of the ‘preference not deference’ rule;

• are delivered in a manner that is commensurate with the Learner’s cognitive ability;

• engage each Learner such that the Learner is active and not passive;

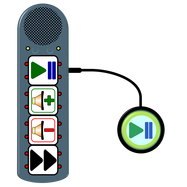

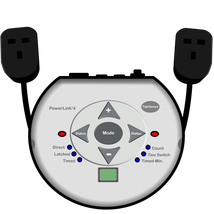

• empower the Learner through improvements in capability/coordination or through the use of available technology;

• empower the Learner through improvements in cognition and communication;

• relate to the possible future experiences and opportunities of the Learner;

• expand possible future experiences and opportunities for the Learner;

• enhance the Learner’s future Quality Of Life;

• are realistic but not pessimistic (self-fulfilling prophecy).

Thus, this page concerns itself with pragmatic and meaningful ideas for use in a post school environment for IEPMLD. You may not agree with all that is suggested but, hopefully, there will be some sections that you will find inspirational. We should look to new possibilities and better futures for this population and not impose unnecesary barriers and limitations and simply because their given 'label' has previously suggested them:

"the existence of learning difficulties so extreme as to present a major obstacle to participation in some of the most basic experiences in life, ought rather to generate educational aims concerned with enabling them to participate in those experiences. An aim which we might express as: 'enabling the child to participate in those experiences which are uniquely human'." (Ware, 1994, page 71)

"It should also become evident that people that may seem to be 'cognitively limited' nevertheless have a great deal of cognitive competence. You will see that without this competence simple things like pointing or eye gaze in a way that is appropriate to the context would not be possible. Such seemingly simple behaviours are still beyond the capabilities of very sophisticated computer simulations and could not occur without considerable knowledge of the world and how to solve problems in that world. (Anderson J. 1990). Hopefully, you will see that even 'cognitively limited' individuals are capable of more than most people think they are (Bray N. & Turner L. 1986, 1987). Facilitators can build on this cognitive base." (Bray N. 1990)

Furthermore, Learners may be better served if the greater part of continuing study had a focus on future activity rather on the development of isolated skills:

"Focusing on activities requires teachers therefore to move from a developmental, skill-based approach, to an ‘activity-based’ intervention approach that considers participation in activities in meaningful contexts as a basis for analysis of educational progress." (Magne Tellevik & Elmerskog, 2009)

"One critical feature of a ‘good’ assessment for this group is that it contributes to improving the individual’s quality of life, by helping teachers

to prioritise learning" (Ware & Donnelly, 2004, page 12).

If the reader feels that aspects of this page are inappropriate or ill-advised or wishes to suggest other areas of development, a contact form is provided at the bottom of the page. Please fell free to use it to contact TalkSense. If any such comment or idea is used on this page then appropriate acknowledgement and credit will be given.

Please Note: This page may be updated from time to time. TalkSense reserves the right to add to, amend or abrogate any section of this page at any time. Should the page change significantly TalkSense will update the 'date counter' such that readers will be alerted. This page was last updated on:

September 28th, 2018

This Page is currently in development. Talksense hopes to have it complete sometime soon. The page will change significantly over time. However you got here, while you are free to browse, please note that some sections are presently missing or incomplete, may alter considerably, and the number order may change. Constructive comments are welcome! (Use form provided at end of page before bibliography)

"Sensory cooking, sensory drama, sensory art, sensory garden, sensory room …. What does the word “sensory” written before the activity or place imply?" (Williams, 2010, page 23)

Not all activities are suitable for inclusion in any post-school curriculum on offer for Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties (hereafter the acronym IEPMLD will be used). As the cartoon suggests, simply placing the word 'sensory' in front of any activity does not, in and of itself, make it an appropriate curricula area; Sensory Russian (assuming the Learners are not Russian), Sensory Neurology, Sensory Welding, etc. are such examples. What then is appropriate and what right have others to decide what is or is not correct in this area of education? This page will attempt to address such issues.

Given that post school education for this group of young people is likely to be both short (one to three years) and expensive (running into tens of thousands of pounds), time should not be wasted on meaningless activities. The focus must be on things that will benefit individual future lives, enhance quality, and ensure a best transition route into a new adult world. This has been recognised for many years:

"Given the key characteristics of the students, what do they need to learn? In order to carry out this exercise successfully, you need to have a clear picture of what their lives are like now, and what they will be like in the future. What are the priorities? Remember that, although the students may have numerous gaps in their learning, you will only have them for two or three years. What are the things which will really

make a difference, even if they do not progress in the others?" (Griffiths & Tennyson, 1997, page 4)

Although specifically addressing schools, Richard Aird said the following in 2001:

"A pupil's school life is a brief affair, and the time in the classroom is a precious time that ought to be dedicated to minimising the handicapping affects of a pupil's disability and enabling the pupil to achieve maximum potential in a broad but relevant curriculum that is unique to the SLD sector and does not smack of the tokenism that has marred the history of the implementation of the National Curriculum in the SLD sector thus far." (Aird, 2001, page 14)

If school life is but a 'brief affair' then how many more constraints are placed on staff and student alike by an even shorter period of study in a post-school provision? Therefore, one might reasonably argue that there is an even greater need for this 'precious time' to have a specific focus as aptly indicated by Aird. Should this focus be different and distinct to that provided by an individual's school experience or should it be an allowance of further time (in some form of school extension) for Learners who, by definition, acquire knowledge at a very different rate to that of their peers?

What do IEPMLD at this time in their lives really need to learn? Do they really need to be continuing placing their hands in mixtures of ingredients (for example) in some form of sensory cookery session as they have presumably been doing throughout their school career? How is this assisting a better quality of life in the future? There may well be a really good rationale for so doing. However, it must be made explicit and all staff (inclusive of the supporting team) must be made aware of this rationale. Indeed, one might ask if IEPMLD are ever likely to be cooking for themselves at all? In which case, why is cookery a part of your curriculum? It might be argued that 'cooking for leisure' is something that an IEPMLD might enjoy and thus choose to do for fun. This might be an acceptable rationale for the provision of this area on the curriculum but should it be compulsory for all Learners? Perhaps Learners should be permitted to choose what they wish to undertake acting as agents making decisions about their own future. Can IEPMLD act as agents? If this is believed not to be the case, does it not follow that one possible curriculum option would be the empowerment of young people through the development of 'agentive' awareness and skills? How can one choose if you do not know how to choose? How can you learn how to choose if you are never given choice? If you are never given choice how can you be an agent?

"One of the reasons that students with disabilities have not succeeded once they leave school is that the educational process has not prepared students with special learning needs adequately to become self-determined young people."

(Wehmeyer & Schalock, 2001, page 2)

For activities to be appropriate for Individuals Experiencing PMLD at F.E. level they must fulfill most of the following criteria. They must show how they:

• are age appropriate within the confines of the ‘preference not deference’ rule;

• are delivered in a manner that is commensurate with the Learner’s cognitive ability;

• engage each Learner such that the Learner is active and not passive;

• empower the Learner through improvements in capability/coordination or through the use of available technology;

• empower the Learner through improvements in cognition and communication;

• relate to the possible future experiences and opportunities of the Learner;

• expand possible future experiences and opportunities for the Learner;

• enhance the Learner’s future Quality Of Life;

• are realistic but not pessimistic (self-fulfilling prophecy).

Thus, this page concerns itself with pragmatic and meaningful ideas for use in a post school environment for IEPMLD. You may not agree with all that is suggested but, hopefully, there will be some sections that you will find inspirational. We should look to new possibilities and better futures for this population and not impose unnecesary barriers and limitations and simply because their given 'label' has previously suggested them:

"the existence of learning difficulties so extreme as to present a major obstacle to participation in some of the most basic experiences in life, ought rather to generate educational aims concerned with enabling them to participate in those experiences. An aim which we might express as: 'enabling the child to participate in those experiences which are uniquely human'." (Ware, 1994, page 71)

"It should also become evident that people that may seem to be 'cognitively limited' nevertheless have a great deal of cognitive competence. You will see that without this competence simple things like pointing or eye gaze in a way that is appropriate to the context would not be possible. Such seemingly simple behaviours are still beyond the capabilities of very sophisticated computer simulations and could not occur without considerable knowledge of the world and how to solve problems in that world. (Anderson J. 1990). Hopefully, you will see that even 'cognitively limited' individuals are capable of more than most people think they are (Bray N. & Turner L. 1986, 1987). Facilitators can build on this cognitive base." (Bray N. 1990)

Furthermore, Learners may be better served if the greater part of continuing study had a focus on future activity rather on the development of isolated skills:

"Focusing on activities requires teachers therefore to move from a developmental, skill-based approach, to an ‘activity-based’ intervention approach that considers participation in activities in meaningful contexts as a basis for analysis of educational progress." (Magne Tellevik & Elmerskog, 2009)

"One critical feature of a ‘good’ assessment for this group is that it contributes to improving the individual’s quality of life, by helping teachers

to prioritise learning" (Ware & Donnelly, 2004, page 12).

If the reader feels that aspects of this page are inappropriate or ill-advised or wishes to suggest other areas of development, a contact form is provided at the bottom of the page. Please fell free to use it to contact TalkSense. If any such comment or idea is used on this page then appropriate acknowledgement and credit will be given.

Please Note: This page may be updated from time to time. TalkSense reserves the right to add to, amend or abrogate any section of this page at any time. Should the page change significantly TalkSense will update the 'date counter' such that readers will be alerted. This page was last updated on:

September 28th, 2018

This Page is currently in development. Talksense hopes to have it complete sometime soon. The page will change significantly over time. However you got here, while you are free to browse, please note that some sections are presently missing or incomplete, may alter considerably, and the number order may change. Constructive comments are welcome! (Use form provided at end of page before bibliography)

IEPMLD

What does IEPMLD stand for and why use this term? IEPMLD is an abbreviated form of either Individual Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties OR for its plural form Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties. The singular or plural form being suggested by context.

I is for Individual ... Everyone is unique. Everyone is an individual. The focus is on the individual, the ability, and not the disability.

E is for Experiencing ... TalkSense chose not to use the word 'with' as this implies some form of unchangeable condition; 'Once PMLD always PMLD'. However, the word 'experiencing' suggests a non-permanent situation and thus, 'Once PMLD but not always'. Experiencing suggests the current situation. However, it also implies a future beyond this state of being. Experiencing also suggests 'experience' in that PMLD is not something that such individuals posses but rather inherit as a result of their experience with the environment. As a parent with a pushchair may become 'handicapped' by a flight of stairs but enabled and included by entrances on one level, the environment in which we might find ourselves defines us. In H.G.Wells' 'The country of the blind' (1911) the sighted man is not king! Indeed, he is the handicapped person as he cannot make his way around in rooms devoid of light which the inhabitants do not require.

P is for Profound ... Profound is the most serious, the most complex, the concerning state of all. Such Individuals can be amongst the most challenging and yet the most rewarding with whom to work.

M is for Multiple... Such Individuals will be experiencing multiple challenges.

L is for Learning... Learning is the question and learning is the answer

D is for Difficulties... The Individual will be experiencing multiple difficulties arising from the present condition. These may include significant sensory impairments as well as additional physical disabilities.

There is no one stereotypical form of an IEPMLD; some are ambulant some are not, some respond readily, some do not, some may experience epilepsy while other may not. Definitions vary:

"Children and adults with profound and multiple learning disabilities have more than one disability, the most significant of which is a profound learning disability. All people who have profound and multiple learning disabilities will have great difficulty communicating. Many people will have additional sensory or physical disabilities, complex health needs or mental health difficulties. The combination of these needs and/or the lack of the right support may also affect behaviour. Some other people, such as those with autism and Down’s syndrome may also have profound and multiple learning disabilities. All children and adults with profound and multiple learning disabilities will need high levels of support with most aspects of daily life." (PMLD Network)

"People with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities are among the most disabled individuals in our community. They have a profound intellectual disability, which means that their intelligence quotient is estimated to be under 20 and therefore that they have severely limited understanding. In addition, they have multiple disabilities, which may include impairments of vision, hearing and movement as well as other problems like epilepsy and autism. Most people in this group are unable to walk unaided and many people have complex health needs requiring extensive help. People with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities have great difficulty communicating; they typically have very limited understanding and express themselves through non-verbal means, or at most through using a few words or symbols. They often show limited evidence of intention. Some people have, in addition, problems of challenging behaviour such as self-injury." (Mansell, 2010)

"People with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities, or profound and multiple learning disabilities (PMLD), can be some of the most

disabled individuals in our communities. They have a profound intellectual disability, which means that their intelligence quotient (IQ) is estimated to be under 20 and therefore they have severely limited understanding. In addition, they may have multiple disabilities, which can include impairments of vision, hearing and movement as well as other challenges such as epilepsy and autism. Most people in this group need support with mobility and many have complex health needs requiring extensive support. People with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities may have considerable difficulty communicating and characteristically have very limited understanding." (BILD 2016)

(Note: For an expanded definition of PMLD see Bellamy et al, 2010)

However PMLD is defined, there are some areas in which all might agree. Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties:

There are however those with dissenting views on such definitions of 'People with PMLD':

"In our view, describing children with PMLD primarily in terms of developmental deficits dehumanises them and potentially leads to their exclusion and degradation." (Simmons & Watson, page 25, 2014)

While taking on board the point being made here, I would doubt that the intention of the majority of individuals attempting a defintion of PMLD was in any way pejorative. Likewise, this section and, indeed, this page is not intended to be viewed in that light. The purpose is to illuminate practices that may deliver an amelioration of the experience (the E in IEPMLD) providing an increased quality of life. Thus, the question is, 'Can PMLD be ameliorated by input from varying professionals (and para-professionals) or is it a permanent unchangeable 'condition' at this moment in time'? In other words, once PMLD always PMLD? Talksense believes that all human beings are capable of learning given an approach adequately tailored to their needs.

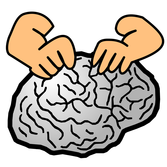

All brains are now understood to be plastic:

"The adult brain, in short, retains much of the plasticity of the developing brain, including the power to repair damaged regions, to grow new neurons, to rezone regions that performed one task and have them assume a new task, to change the circuitry that weaves the neurons into the networks that allows us to remember, feel, suffer, think, imagine, and dream." (Begley, 2009, page 7)

"The effect of brain damage or lack of parts of the brain, by definition, will restrict the number of neurons present from the outset and, of course, also restrict the numbers of synapses that can develop. However, if we remember that synapses are formed throughout our lives (brain plasticity) there are always possibilities that people with PMLD can make new connections and learn new things just like typically developing people. Sensory stimulation, experiences with objects and new activities are just as important whatever the age of the learner." (Lacey, 2015, page 44)

Given advances in the therapies, medicine, care and education, it must be possible to harness the brain's plasticity to take an individual Learner from a state of pre-intentional responses to stimuli to one of intentionality, raising the individual's level of consciousness of the world to a point where the Learner can no longer be classified as having a profound cognitive condition. No claim is being made that any Learner will metamorphose from PLMD to Ph.D. rather that all Learners can continue to make progress given the appropriate environment, tools, and input. Will such progress guarantee each and every Learner a brighter future? That would be a foolhardy claim to make. However, it may be claimed that it increases the possibility of such a position.

In 2006 Ian Lamond said:

"I have where possible tried to avoid referring to anyone as disabled or as having a PMLD. This is at least in part because of my own belief that disability, whether physical disability or learning disability, is not something that a person has. My own view is that disability is something that is experienced or encountered as a result of the environment a person is in, or the people that are around them." (page 7)

Talksense likes to discuss people experiencing severe and profound learning difficulties using the phrase 'Stricken not Stupid' where 'stricken' denotes an impairment in cognitive functioning as a result of an (cerebral) injury or some agency, outside the control of the individual, impairing proper progression.

I is for Individual ... Everyone is unique. Everyone is an individual. The focus is on the individual, the ability, and not the disability.

E is for Experiencing ... TalkSense chose not to use the word 'with' as this implies some form of unchangeable condition; 'Once PMLD always PMLD'. However, the word 'experiencing' suggests a non-permanent situation and thus, 'Once PMLD but not always'. Experiencing suggests the current situation. However, it also implies a future beyond this state of being. Experiencing also suggests 'experience' in that PMLD is not something that such individuals posses but rather inherit as a result of their experience with the environment. As a parent with a pushchair may become 'handicapped' by a flight of stairs but enabled and included by entrances on one level, the environment in which we might find ourselves defines us. In H.G.Wells' 'The country of the blind' (1911) the sighted man is not king! Indeed, he is the handicapped person as he cannot make his way around in rooms devoid of light which the inhabitants do not require.

P is for Profound ... Profound is the most serious, the most complex, the concerning state of all. Such Individuals can be amongst the most challenging and yet the most rewarding with whom to work.

M is for Multiple... Such Individuals will be experiencing multiple challenges.

L is for Learning... Learning is the question and learning is the answer

D is for Difficulties... The Individual will be experiencing multiple difficulties arising from the present condition. These may include significant sensory impairments as well as additional physical disabilities.

There is no one stereotypical form of an IEPMLD; some are ambulant some are not, some respond readily, some do not, some may experience epilepsy while other may not. Definitions vary:

"Children and adults with profound and multiple learning disabilities have more than one disability, the most significant of which is a profound learning disability. All people who have profound and multiple learning disabilities will have great difficulty communicating. Many people will have additional sensory or physical disabilities, complex health needs or mental health difficulties. The combination of these needs and/or the lack of the right support may also affect behaviour. Some other people, such as those with autism and Down’s syndrome may also have profound and multiple learning disabilities. All children and adults with profound and multiple learning disabilities will need high levels of support with most aspects of daily life." (PMLD Network)

"People with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities are among the most disabled individuals in our community. They have a profound intellectual disability, which means that their intelligence quotient is estimated to be under 20 and therefore that they have severely limited understanding. In addition, they have multiple disabilities, which may include impairments of vision, hearing and movement as well as other problems like epilepsy and autism. Most people in this group are unable to walk unaided and many people have complex health needs requiring extensive help. People with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities have great difficulty communicating; they typically have very limited understanding and express themselves through non-verbal means, or at most through using a few words or symbols. They often show limited evidence of intention. Some people have, in addition, problems of challenging behaviour such as self-injury." (Mansell, 2010)

"People with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities, or profound and multiple learning disabilities (PMLD), can be some of the most

disabled individuals in our communities. They have a profound intellectual disability, which means that their intelligence quotient (IQ) is estimated to be under 20 and therefore they have severely limited understanding. In addition, they may have multiple disabilities, which can include impairments of vision, hearing and movement as well as other challenges such as epilepsy and autism. Most people in this group need support with mobility and many have complex health needs requiring extensive support. People with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities may have considerable difficulty communicating and characteristically have very limited understanding." (BILD 2016)

(Note: For an expanded definition of PMLD see Bellamy et al, 2010)

However PMLD is defined, there are some areas in which all might agree. Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties:

- typically have more than one disability;

- have a profound cognitive disability;

- have especial difficulty with communicating;

- require high levels of support with virtually every aspect of daily life;

- may have additional sensory or physical disabilities, complex health needs, or mental health difficulties;

- may exhibit behaviours that others find challenging.

There are however those with dissenting views on such definitions of 'People with PMLD':

"In our view, describing children with PMLD primarily in terms of developmental deficits dehumanises them and potentially leads to their exclusion and degradation." (Simmons & Watson, page 25, 2014)

While taking on board the point being made here, I would doubt that the intention of the majority of individuals attempting a defintion of PMLD was in any way pejorative. Likewise, this section and, indeed, this page is not intended to be viewed in that light. The purpose is to illuminate practices that may deliver an amelioration of the experience (the E in IEPMLD) providing an increased quality of life. Thus, the question is, 'Can PMLD be ameliorated by input from varying professionals (and para-professionals) or is it a permanent unchangeable 'condition' at this moment in time'? In other words, once PMLD always PMLD? Talksense believes that all human beings are capable of learning given an approach adequately tailored to their needs.

All brains are now understood to be plastic:

"The adult brain, in short, retains much of the plasticity of the developing brain, including the power to repair damaged regions, to grow new neurons, to rezone regions that performed one task and have them assume a new task, to change the circuitry that weaves the neurons into the networks that allows us to remember, feel, suffer, think, imagine, and dream." (Begley, 2009, page 7)

"The effect of brain damage or lack of parts of the brain, by definition, will restrict the number of neurons present from the outset and, of course, also restrict the numbers of synapses that can develop. However, if we remember that synapses are formed throughout our lives (brain plasticity) there are always possibilities that people with PMLD can make new connections and learn new things just like typically developing people. Sensory stimulation, experiences with objects and new activities are just as important whatever the age of the learner." (Lacey, 2015, page 44)

Given advances in the therapies, medicine, care and education, it must be possible to harness the brain's plasticity to take an individual Learner from a state of pre-intentional responses to stimuli to one of intentionality, raising the individual's level of consciousness of the world to a point where the Learner can no longer be classified as having a profound cognitive condition. No claim is being made that any Learner will metamorphose from PLMD to Ph.D. rather that all Learners can continue to make progress given the appropriate environment, tools, and input. Will such progress guarantee each and every Learner a brighter future? That would be a foolhardy claim to make. However, it may be claimed that it increases the possibility of such a position.

In 2006 Ian Lamond said:

"I have where possible tried to avoid referring to anyone as disabled or as having a PMLD. This is at least in part because of my own belief that disability, whether physical disability or learning disability, is not something that a person has. My own view is that disability is something that is experienced or encountered as a result of the environment a person is in, or the people that are around them." (page 7)

Talksense likes to discuss people experiencing severe and profound learning difficulties using the phrase 'Stricken not Stupid' where 'stricken' denotes an impairment in cognitive functioning as a result of an (cerebral) injury or some agency, outside the control of the individual, impairing proper progression.

1. School's Out

"School's out forever.

School's been blown to pieces"

The 1972 Alice Cooper hit 'School's Out' might be reinterpreted to infer the message of this section of the webpage, namely that Specialist Further Education in whatever form that takes (unit additional to school, residential college of specialist FE, unit in FE college, ...) is NOT school, should not be seen as school, and should have a very different look and feel to school. Whilst this might be difficult to achieve in an FE unit in actual school building there are certain fundamentals that are highly recommended nevertheless:

School's been blown to pieces"

The 1972 Alice Cooper hit 'School's Out' might be reinterpreted to infer the message of this section of the webpage, namely that Specialist Further Education in whatever form that takes (unit additional to school, residential college of specialist FE, unit in FE college, ...) is NOT school, should not be seen as school, and should have a very different look and feel to school. Whilst this might be difficult to achieve in an FE unit in actual school building there are certain fundamentals that are highly recommended nevertheless:

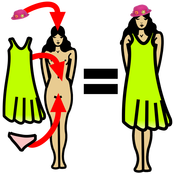

- The Learners have a new status as adults and should be treated as such even though they be operating at a level far below their chronological age;

- The system of time management in the FE setting does not have to follow that of school;

- As the your country's curriculum no longer is likely to apply, you may adopt a curriculum tailored to the specific needs of the Students;

- The dress code should be less formal and more individualistic;

- Age appropriate materials, supplies, and attitudes (see section on age appropriateness later on this page);

- Typically Further Education students do not stay in one classroom all day, they move from seminar room to seminar room;

- Typically Further Education students occupy a separate space to younger Learners;

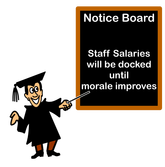

- The language employed by staff should be different. For example, it is not uncommon to hear praise of the form 'Good boy/girl' in a school setting but this is strictly taboo in further education. Whilst you might use 'Good man/woman' in place of the former, 'Good work' might be even more appropriate or 'That's good <Name>' employing the Learner's first name instead or 'boy' or 'girl'. If you phrase all remarks as though you were talking to a (younger) colleague then you'll not go astray. Saying 'good boy' to a younger colleague would seem highly patronising and be totally inappropriate but 'That's brilliant Ben' or 'Fantastic Fiona' would be perfectly acceptable;

- The student body should have a 'voice' with management listening to learners and providing a framework for the students to

inform their own learning and adapt the provision were possible. This is a very challenging aspect of FE management when providing for IEPMLD; - Time in FE is likely to be short and therefore transition to possible appropriate future placements must be high on the agenda.

2. Begin the Begin

In the children's classic 'Alice in Wonderland' (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) during the trial of the Knave of Hearts, the King says to the white rabbit when he asks where he should begin:

“Begin at the beginning," the King said, very gravely, "and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

It may seem obvious that, in teaching Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties (IEPMLD), we need to begin at the beginning, carry on until we get to the place we intended for our session, and then stop but what does that actually mean in practice? Where is the beginning? How should we carry on? How do we know that we have reached 'the end'? How do we know that the IEPMLD have made that journey along with us?

"How to make the process meaningful and accessible to children with PMLD and the practicalities of sharing in a transparent manner is practically challenging." (Goodwin, 2013, page 24)

There will have been times in your life when you have been listening intently to an explanation but, as the explanation proceeded, somewhere along the way you lost the plot and failed to grasp what was being said. For example, when listening to theoretical physics at the quantum level I start out comprehending (at least I think I comprehend) what is being said but, as the explanation moves deeper and deeper, I find myself completely confused and not understanding. Can my understanding be improved? Can the structure of my brain be altered such that my intelligence is developed so that I can understand what is being said? Perhaps there are ways of achieving that but isn't there a much, much simpler solution? Rather than improve understanding why don't we improve the teaching? If the message was conveyed in a way which was commensurate with the level of my understanding then perhaps I might be able to move further along the pathway. It is therefore important that the teaching staff are aware of 'considered best practice' and the course that they should follow:

"A handicapped child represents a qualitatively different, unique type of development.... If a blind or deaf child achieves the same level of development as a normal child, then the child with a defect achieves this in another way, by another course, by other means; and, for the pedagogue, it is particularly important to know the uniqueness of the course along which he must lead the child. This uniqueness transforms the minus of the handicap into the plus of compensation." (Vygotsky, 1993)

In teaching IEPMLD we must obey at least eight fundamental rules:

Take the Trouble to start in the right place; that is with what the Learners already know and understand;

Explain using methodologies and terms that the Learners understand;

Appropriate Amounts: restrict the volume of new information delivered at any one time; single task - don't demand multi-tasking;

Clarity before accuracy:

Hold Heedfulness: ensure attention; show enthusiasm; inhibit interruptions;

Investigate comprehension: check for clues that confirm comprehension; evaluate understanding;

Number of repetitions: Not once but repeated over and over as many times as necessary; Take the Time;

Give Glee: Find Fun; Create Challenge but Suppress Stress; Learn to Love; Embrace the Enjoyable.

The above listing does not address 'what' should be taught but, rather, 'how'. The'what' can be found throughout the varying sections on this webpage and will therefore not be addressed here.

TEACHING requires that staff take the trouble to discover what the Learners already know and understand and build from there.

"When I'm working with people with PMLD, I always remind myself of the adage: 'start where the learners are and not where you think they should be……but you can't leave them there'. I know I must expect people with PMLD to learn how to think but I must also be realistic and build on what I can see is happening. I can't just give sensory experiences and hope that learning will take place. I need to know how many times to repeat the stimulus, what the likely reaction will be, how long it takes for that reaction to occur, where the best reactions take place, who gets the best reactions. It has to be very precise or I may not be 'where the learner is'. Typical learners can learn as long as the input/activity is roughly in the right cognitive area." (Lacey, 2015, page 46)

Too often materials are utilised in classrooms using concepts that are in advance of the current comprehension levels of the Learners: For example, some sensory stories Talksense have witnessed were about space and space flight. While the staff might have argued that the topic was irrelevant because the purchase was to have sensory experiences and to have fun (all well and good), if the topic is irrelevant then why not make it something that the Learners might already comprehend whilst still providing the sensory experiences and the fun (Giving Glee)? Of course, Talksense's view is that topics are not irrelevant and that they should always match the current level and needs of the individual Learners concerned. The question becomes, 'how can we ascertain what the Learners know and understand?'

Assessment of the current understanding of an IEPMLD is not a straightforward nor an easy task:

"Anyone who teaches pupils/ students with PMLD will be aware how difficult it is to assess the learning of the most disabled members of this group in a meaningful and holistic way". (Ware & Donnelly, 2004, page 12)

Routes to Learning (2006) offers a possible strategy for assessing the current level of knowledge of an IEPMLD. It is based on observations of an individuals behaviour when provided with varying forms of stimulation in controlled situations. It also emphasises that the starting point is 'a step you know they can already do':

"In order to use the chart to assess a pupil you start at a step you know they can already do, and work down through the steps until they do not respond. The routemap then shows a number of possible learning pathways to the next major ‘junction’. This encourages the adoption of problem solving approaches, for example when barriers to learning are encountered." (Ware & Donnelly, 2004, page 14)

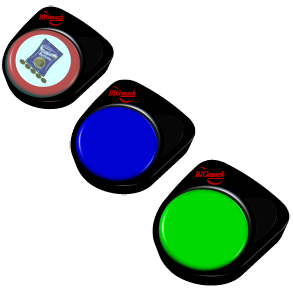

However, even the Route Map has issues (even though Talksense has the greatest respect for the writings and works of Jean Ware)! For example, Route Map step 37 is 'communicates choice to attentive adult' for which its suggestion is to 'offer two items simultaneously. Observe the learner closely for obvious or increased attention to one of the items which communicates his/her preference'. The Route Map provides four observation criteria (smiling, eye pointing, reaching, and turning towards a preferred item) as apparent evidence of ability in this area. We can ask ourselves is 'smiling' in the presence of an object an indication of a preference? While it may be indicative in some circumstances and for some individuals it does not follow that it is necessarily an infallible and objective assessment of ability. Let's suppose that a learner reaches for an object; does this indicate that a choice has been made? Even this action is problematic! To analyse this extensively is beyond the scope of this page (see the choice page this web site for further explanation of this area). However, perhaps the Learner has a right side bias and will always select an item positioned in his/her right sensory field. Perhaps the Learner is attracted to 'light' and the item 'selected' just happened to glint in the sunlight a little more than the alternative. In either of these cases can we claim that the Learner is making a conscious choice? That is NOT to downplay the value of the Route Map nor to suggest it is not a good tool in the special education armoury, rather to challenge your thinking on what constitutes an effective assessment of ability in an IEPMLD.

"Eliminate all other factors, and the one which remains must be the truth" (Sherlock Holmes: The Sign of Four, 1890, Chapter 1, p. 92, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle)

In order to ascertain present understanding, we must scrutinise any response to a stimulus and, as Conan Doyle suggests (see quote above) 'eliminate all other factors' to discover any possible 'truth'. Thus, in reaching for an object, can we state that an individual has made a conscious choice if we have not (i) searched for alternative explanations and (ii) eliminated each in turn? It is when an observable behaviour can be explained by only one rationale (all others [including chance] being dismissed) that we might hypothesise that the behaviour B is as a result of an antecedent ability A of the Learner in question. To assume otherwise is to build castles from sand which might soon be washed away completely.

'Explain using methodologies and terms that the Learners understand' also provides us with a similar problem; that is, how do we know what the Learners understand?! If I am not sure of understanding unless evidenced by factors covered in the previous chapter then why would I utilise language, subject matter (topics), and or methodologies that are obviously beyond a Learners present level of cognition? Yet, I see this quite often in special education classrooms! For example, I hear stories being told of mythical creatures, space travel, even epic sea voyages which are beyond the every experiences of most if not all in the class no matter what sensory stimulation is being utilised to bring the story 'to life'. Why can't the stories concern experiences that the individuals in the group are likely to have encountered? Why not utilise everyday events using simple everyday language to provide the basis for learning and sensory stimulation?

Teachers tend to explain using the medium of language; there is a lot of it in any classroom that you visit. However, for IEPMLD language alone may not always be the best medium for information exchange. Indeed, language may have to be ruled out sometimes:

"It wasn't that I could not think anymore. I just didn't think in the same way. Communication with the external world was out. Language with linear processing was out. But thinking in pictures was in. Gathering glimpses of information, moment by moment, and then taking time to ponder the experience, was in." (Bolte Taylor, 2008, page 75)

Appropriate Amounts: restrict the volume of new information delivered at any one time; single task - don't demand multi-tasking

"Some may find difficulty in responding to stimuli through competing sensory channels, e.g. a learner may be unable to carry out a tactile search while listening to the teacher talking. In the early stages of development it may be appropriate to limit input to one sense only." (Northern Ireland Curriculum 2012)

"When it comes to information, it turns our that one can have too much of a good thing.,At a certain level of input, the law of diminishing returns takes effect; the glut of information no longer adds to our quality of life, but instead begins to cultivate stress, confusion, and even ignorance. Information overload threatens our ability to educate ourselves and leaves us more vulnerable as consumers and less cohesive as a society. For most of us, it actually diminishes our control over our own lives." (Shenk, 2003, page 395)

"The need to avoid an overload of sensory information has always been foremost in planning, and in some instances, it is the contrast between one section and the next which provides the stimulus to which pupils respond." (Henderson, 205, page 19)

"The trouble was that she (the teacher) gave me too many instructions. By the time I got to where I needed to be I had forgotten all but the last one and that didn’t make any sense on its own. So I hid." (Emma quoted in 'A Guide to Specific Learning Difficulties', 2017, page 4)

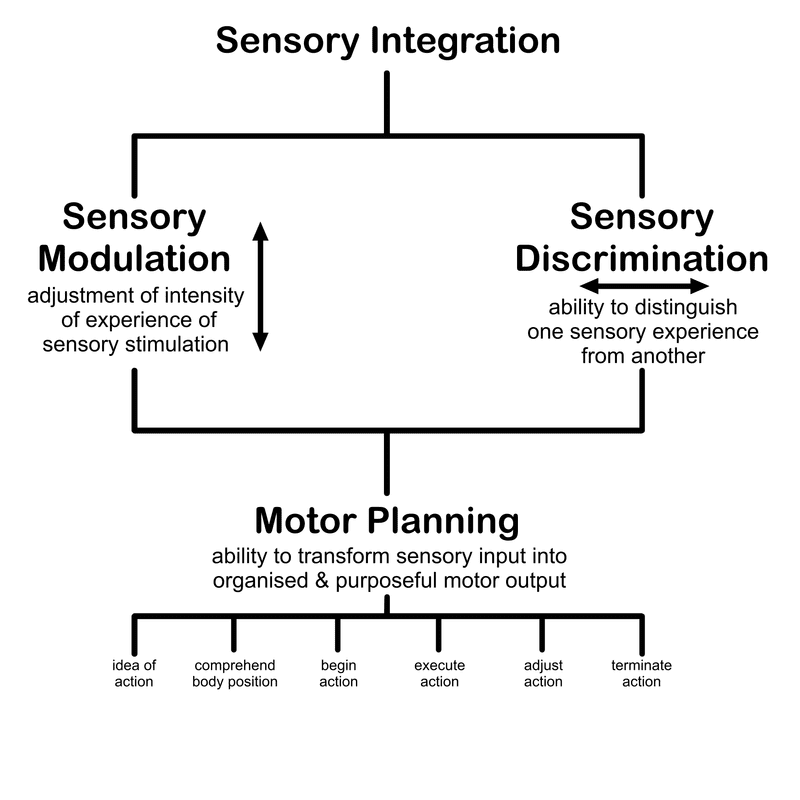

Almost everyone has heard the term 'information overload' which, in essence, means difficulty in (or a total lack of) comprehension as a result of too much information being provided at any one time. Information overload takes on more significance when the individual Learner concerned has a sensory processing disorder (see, for example, Koziol, Ely Budding, & Chidekel, 2011; May-Benson, 2011; Thye, Bednarz, Herringshaw, Sartin, & Kana, 2017). A sensory processing disorder may be defined as a failure to respond appropriately to the requirements of an environment as a result of inadequate processing and or integration (see the work of Jean Ayres, 1970, 1972, 1973, 1974 and see section on 'Sensory Integration' lower down on this webpage) of incoming sensory data (for a useful Sensory Processing Disorder checklist go here). In some cases, the Learner may be unable to screen out background sensory input from one or more of the sense organs such that the input becomes overwhelming:

"One of my sensory problems was hearing sensitivity, where certain loud noises, such as a school bell, hurt my ears. It sounded like a dentist drill going through my ears." (Grandin,1992)

"Some children with more severe sensory problems may withdraw further because the intrusion completely overloads their immature nervous system. They will often respond best to gentler teaching methods such as whispering softly to the child in a room free of florescent lights and visual distractions. Donna Williams (explained that forced eye contact caused her brain to shut down. She states when people spoke to her, their words become a mumble jumble, their voices a pattern of sounds. She can use only one sensory channel at a time. If Donna is listening to somebody talk, she is unable to perceive a cat jumping up on her lap. If she attends to the cat, then speech perception is blocked. She realized a black thing was on her lap, but she did not recognize it as a cat until she stopped listening to her friend talk." (Grandin,1996)

"Imagine driving a car that isn't working well. When you step on the gas the car sometimes lurches forward and sometimes doesn't respond. When you blow the horn it sounds blaring. The brakes sometimes slow the car, but not always. The blinkers work occasionally, the steering is erratic, and the speedometer is inaccurate. You are engaged in a constant struggle to keep the car on the road, and it is difficult to concentrate on anything else." (Greenspan, 1996)

"It was obvious that I perceived incoming stimulation as painful. Sound streaming in through my ears blasted my brain senseless so that when people spoke, I could not distinguish their voices from the underlying clatter of the environment." (Bolte Taylor, 2008, Page 72)

"At the most elementary level of information processing, stimulation is energy, and my brain needed to be protected, and isolated from obnoxious sensory stimulation, which it perceived as noise." (Bolte Taylor, 2008, Page 112)

"When people experience sensory overload or anxiety their behaviour may seem a little different to others, they aren't having a tantrum or being uncooperative they are simply overwhelmed and trying to cope best they can." ('A Guide to Specific Learning Difficulties', 2017, page 23)

In other cases, the information simply does not get through or gets scrambled along the way:

"The next thing you need to do is to control the rate and complexity of your communications with a child who has receptive language problems. A barrage of auditory input that overloads his 'wires' will result in lost bits of data. The child may remember some of it, but not all. What he does remember may be scrambled. Slow down your pace and give him a chance to absorb one thing before piling another on top of it." (Utley Adelizzi & Goss, 2001, page 111)

Thus, everything staff do together with IEPMLD should be simple. This includes the language used to convey information to Learners; it should be simple. The acronym ‘KISS’ (Keep It Short & Simple) should become a byword with staff avoiding ambiguity at all costs. Learners would be much better served if staff were to use the skills used by teachers of the deaf (Quigley S. & Kretchmer R. 1982, Wood D., Wood H. H., Griffiths A., & Howarth A. 1986):

Of course, the understanding of language itself may be problematic for many if not all of our Learners. However, ‘What is being said’, is far more than speech: It includes the staff member’s tone, facial expressions, gestures, and body language, as well as cues given from contextual information. Indeed, it has been demonstrated (Mehrabian & Ferris 1967) that, in presentations before groups of people, 55% of the impact is determined by body language, 38% by tone, and only 7% by the actual content of the presentation. As early as 1958, Bruce (Bruce D. 1958) showed that words used in a meaningful context is better understood than language used out of context. 'A meaningful context' can occur naturally (as in a park or a supermarket) or be 'engineered' by staff and both can be augmented with the addition of other sensory cues to aid comprehension:

"Children who are presented with information in a verbal medium (that is, the spoken or written word) frequently have greater difficulty in understanding or decoding the verbal input than they would have in understanding a nonverbal input(that is, a nonverbal event that is perceived visually or tactually)." (Milgram, N. 1973 page 167)

'Total communication' is a philosophy stressing the importance of multimodal forms of communication (which had its roots in the 1960s). Those supporting such an approach advocated the use of all appropriate means of input and output (for example, objects, pictures, symbols and signs in addition to speech) to facilitate communication and comprehension (see, for example, Denton,1970; Vernon,1972; Garretson,1976; Evans, 1982; Zangari, Lloyd, & Vicker, 1994). However, even here, there can be sensory overload!

Clarity before accuracy

While something can be completely accurate it can, at one and the same time, not be clear. An accurate depiction might involve too much information which, as the section above highlights, can be confusing while a simpler and shorter explanation might be better understood. Clarity is more likely to equate with understanding. If we teach clearly, our Learners are more likely to understand. This takes a great deal of effort, but when we speak in a 'language' that our Learners have a chance of understanding then there is hope of meaningful progression. It is important not to confuse the use of linguistic forms that are in advance of Learner's level of understanding with accuracy when their use will simply confuse the Learners. Translating and transforming more advanced terminology into simpler, comprehensible methodological approaches will help provide clarity.

"Sometimes in this sea of information we lose sight of the fact that there is another way to sharpen teaching and strengthen the educational impact of our institutions—improving the clarity and organization of our classes. Although this may not sound as transformative or exciting as some of the pedagogies and high-impact practices described above, it turns out to be very important for student learning, and it can pay dividends regardless of whether it is applied with these innovative pedagogies and practices or used on its own." (Blaich, Wise, Pascarella, & Roksa, 2016, page 6)

"Because it was very difficult for my ears to distinguish a single voice from background noise, I needed the question to be repeated slowly and enunciated clearly. I needed calm , clear communication. I may have had a dense expression on my face and appeared ignorant, but my mind was very busy concentrating on the acquisition of new information. My responses came slowly. Much too slowly for the real world ." (Bolte Taylor, 2008, page 76)

Hold Heedfulness

"Considerable evidence gathered over several decades highlights the importance of maximising the arousal and connectivity of individuals in this group, who are typically affected by a myriad of intrapersonal complications including sensory, intellectual and physical challenges." (Arthur-Kelly, Foreman, Bennett & Pascoe, 2008, page 162)

"An important focus of attention in the learning process is the alertness and attention of people with PMD. In research, these characteristics

are put forward as an essential basis for learning and developing (Arthur, 2003, 2004; Foreman, Arthur-Kelly, Pascoe, & King, 2004; Guess, Roberts, & Rues, 2002)." (Petry et al, 2007c, page 133)

To hold heedfulness is to assure attention. How do we hold heedfulness by assuring attention? There are a number of factors that can affect the attentiveness of an individual Learner in any group: Specific 'aspects' that can creep into any session have the ability to affect desirable outcomes. There may be several such 'aspects' but, here, we will deal with just two: waiting and distractions. It should be noted that it is common to find occurrences of self stimulatory behaviour amongst the population of Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties. The aetiology of such behaviours is complex but one causal factor is a lack of extrinsic stimulation. As such, Individuals who are sitting idle and spending periods waiting will tend to self stimulate. We should seek to extinguish Self Stimulatory Behaviours (See, for example, Rincover, A. 1978).

"when engaged in these behaviors, the children were particularly hard to 'reach' socially and difficult to teach.Their attention seemed to focus exclusively on their own behaviors, making them oblivious to all but the strongest external stimuli." (Lovaas, Newsom, & Hickman 1987 page 46)

While some Learners may self stimulate, others may fall asleep and some may even resort to behaviours that others may find challenging perhaps in an attempt to gain attention. None of these are desirable and, thus, periods of idleness need to be reduced to a minimum. Behaviours that others may find challenging may also act as a distraction from the goals of any particular session. If Learners are focused elsewhere, they are unlikely to be attending to a specific aspect of the session as well. As such staff should plan to try to reduce all external distractions: for example, you might put a 'do not disturb' sign on the door handle outside the room to notify others that, unless it is an emergency, they should not enter. As any aspect of a session is likely to be illustrated through the differing senses, all competing sensory input from other sources needs to be attenuated: you will want a quiet place to work in which you can control the ambiance as much as is possible: can you control the light, the sound, and the smells? It might be unwise therefore to consider delivering a Sensory Story (for example) in the classroom next to the dining hall in the period before lunch when the kitchen noises and smells are still pervasive even with a closed door.

Investigate comprehension

"Much of the checking for understanding done in schools is ineffective." (Fisher & Frey, 2014, page 1)

Investigating comprehension is not quite the same thing as an assessment of present understanding and, thus, starting in the right place. It involves means of checking as to whether what is currently being taught is making sense to the Learner, is understood and, thus, the Learner is making progress. Indeed, there is little point in preparing the most fantastic all singing and dancing sessions if the Learner is sitting there oblivious to it all throughout, and the session would have had as much impact if one staff member had just sat with the Learner and watched a recording of a documentary on quantum physics with very little interaction!

As any session proceeds, it is important that we investigate the comprehension of the Learner(s). The question now becomes just exactly how do we do that?

"Checking for understanding is an important step in the teaching and learning process. The background knowledge that students bring into the classroom influences how they understand the material you share and the lessons or learning opportunities you provide. Unless you check for understanding, it is difficult to know exactly what students are getting out of the lesson. In fact, checking for understanding is part of a formative assessment system in which teachers identify learning goals, provide students feedback, and then plan instruction based on students’ errors and misconceptions." (Fisher & Frey, 2014, page 2)

Controlling comprehension will involve 'holding heedfulness' as highlighted in the prior section as, if the Learner is not attending, it is very unlikely s/he is comprehending the purpose of the session at that point in time. However, attention, although very important, does not in and of itself, guarantee comprehension; we can attend very careful to a lecture on a difficult subject and yet leave the lecture hall completely confused! That then brings us full circle back to some of the other other issues detailed in the sections of 'TEACHING' detailed both above and below such as ensuring we are providing just the right amount of information, at the right level for the Learners, and making it fun and memorable. Even then, given the aforementioned items, how do we know if an individual has 'taken in' the purpose (objectives) of the session?

The use of a 'Total Communication' approach may be enlisted better to improve Learner comprehension:

"Consultation approaches with children with learning disabilities increasingly use total communication methods in order to ensure as

far as possible that meaning is understood by the child and the caregiver. However, many PMLD children who communicate pre-intentionally

may not have been listened to due to perceived issues of their capacity and the validity and ethicality of such approaches." (Goodwin, 2013, page 21)

However, while such an approach makes significant use of multiple modalities in conveying information with the aim of improving comprehension, it does not guarantee it nor does it check for it. While interpretations of Learner behaviours by Significant Others during sessions utilising Total Communication may suggest understanding, it is easier to assume a positive when you have a significant emotional investment in the outcome:

"Those who are most familiar with an individual and most likely to interpret their reactions appropriately are also likely to be those with the highest degree of emotional involvement." (Ware, 2004, page 32)

While it does not follow that Significant Others are always wrong in their 'assumptions of understanding' of Learners in their charge, their assumptions are still assumptions and not objectively verifiable facts. Is it possible to acquire objectively verifiable facts in the teaching and learning process with IEPMLD? While not as straightforward a process as with the assessment more able peers, there are some things which might indicate understanding in IEPMLD:

In the example above (a real life case) what can we claim about 'A's comprehension? Can we claim cause and effect skills (contingency awareness)? If so, why? As quoted earlier, Sherlock Homes said:

"Eliminate all other factors, and the one which remains must be the truth" (Sherlock Holmes: The Sign of Four, 1890, Chapter 1, p. 92, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle)

As we are claiming that the use of the switch to activate the video is evidence of contingency awareness comprehension in student 'A' what other possible explanations for the behaviour exist and can these be eliminated?

Number of repetitions

In the USA there is hardly a house to be found that doesn’t have a basketball hoop fixed to its wall and a child practising the necessary skills to become proficient at the game. The same is true of soccer in the U.K. We think nothing of a child spending hundreds of hours in such practice. Touch typists require approximately 200 hours of practice. Practice requires a number of repetitions; repetitions that provide an opportunity for the Individual to grasp the essence of that which is being conveyed or to begin to master a skill. Remember, IEPMLD require repetitions really regularly!

"Constant repetition and a great deal of support will be needed to generalise learning into new situations." (MENCAP, 2008, Page 4)

" Essentially, I had to completely inhabit the level of ability that I could achieve before it was time to take the next step. In order to atain a new ability, I had to be able to repeat that effort with grace and control before taking the next step." (Bolte Taylor, 2008, page 90)

"I needed my caregivers to teach me with patience. Sometimes I needed them to show me something over and over again., until my body and brain could figure out what I was learning" (Bolte Taylor, 2008, page 119)

"Repetition provides rehearsal and consolidation of known games and activities, and a continuous secure base and reference points. Through repetition variations occur, leading to new games and activities." (Quest For Learning, 2009, page 41)

"In order to meet their specific learning needs, a curriculum designed for pupils with MSI must provide frequent repetition and redundancy of information" (Murdoch et al, 2009, page 12)

"Remember that short, daily repetition is more valuable than longer, weekly sessions" (Association of Teachers and Lecturers, 2013, page 4)

"Focused on repeating sequences of sensory storytelling with the same three stories told every week for six weeks and then another three stories. The would allow for,the development of a pattern of sensory experiences using voice and body, and words and multi sensory objects." (Dowling, 2011, page 29)

"The student that I had the most progress with, was the student that I had every day, was seeing the symbols every day, over and over and over again." (Bruce, Trief, and Cascella, 2011)

"The more you bring a memory back to mind, the stronger it becomes. Boring but true. At the neural level, with each repetition you are strengthening the synaptic connections underlying the memory, allowing it to resist interference from other memories or general degradation. Repetition engages the neural networks related to our attention system; in other words, we tend to remember what we pay attention to." (Suzuki, 2015, page 75)

"So if people with PMLD have such difficulties with memory, how can they learn? As was suggested earlier in this article, sheer repetition is likely to be the answer. If John can learn to open his mouth to anticipate food on the spoon, then he can learn to anticipate other things,

but not without a tremendous amount of repetition. In my experience we do not repeat activities sufficiently. We want to give learners with PMLD an interesting life with lots of different sensory experiences, where perhaps we should be concentrating on a few that are repeated

many times." (Lacey, 2015, page 44)

The Murdoch et al quote (2009) above notes that IEPMLD curricula should contain 'redundancy'. Redundancy implies that the teaching should contain restatements of bits of information in slightly varying form so that each statement builds slowly on the preceding one (The orange needs to be cut; a knife is good for cutting an orange; let's get a knife to cut the orange; cut the orange with the knife)(see Blank and Marquis 1987). This leads to a re-formulation of the point made earlier on this page recommending the use of short sentences: it now becomes 'use short sentences but build in considerable redundancy such that each sentence builds into the next and helps to ease Learner comprehension':

"The alteration in the teacher's pattern of language has definite advantages for language disabled children. As noted above, the expanded verbalization is largely redundant. As a result, if children attend, they have the opportunity to have the information reinforced. By contrast, if their attention wavers, they still have the opportunity to hear the message that might have been missed. In addition, the expanded messages provide children with more time between questions, thereby meeting their needs to have longer periods in which to process information. Finally, in making the implicit explicit, the demands for inferential reasoning on the children's part are reduced, thereby bringing the conversation within manageable proportions." (Blank and Marquis. 1987)

Redundancy aids interaction between the Staff and the Learner. It eases the mental effort required by the Learner to comprehend the narrative. Consider the following two texts:

The second text example holds considerable redundancy but only increases the text by about 10 words. No assumption is made of 'carry-over' and intra-phrasal comprehension. The concepts are made explicit in each phrase. Each phrase builds on the next. By building redundancy into communication interactions with Learners in any presentation, staff assist comprehension, which should never be taken for granted.

Give Glee; Suppress Stress, Learn to Love and Find the Fun

"One of Sue’s most fundamental signals, and the basis of her style of celebrating his behaviour, is that she is really having a good time. She is not pretending to have fun for his sake, she isn’t shaping and styling her behaviour purely for his benefit, she is literally, unequivocally, unashamedly having a great time and indulging her own needs for enjoyment." (Nind, & Hewett, 1994 page 49)

If it is not fun for you or it is not fun for the user or for both of you, then:

Long term stress is toxic to the developing brain and, indeed, to all brains (Gunnar & Vazquez, 2006; Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007; Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar, & Heim 2009, Shonkoff, 2011; McEwen, 2012; Eiland & Romeo 2013; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2014). Schools and Colleges should not be stressful environments: not for staff and not for students. We should do everything in our power to suppress the stress, find the fun and give glee. While short term stress (such as the school inspectors coming in?!) might be, on limited occasions, beneficial these should not be turned into long term stressors:

"Studies indicate that toxic stress can have an adverse impact on brain architecture. In the extreme, such as in cases of severe, chronic

abuse, especially during early, sensitive periods of brain development, the regions of the brain involved in fear, anxiety, and impulsive responses may overproduce neural connections while those regions dedicated to reasoning, planning, and behavioral control may produce fewer neural connections. Extreme exposure to toxic stress can change the stress system so that it responds at lower thresholds to events that might not be stressful to others, and, therefore, the stress response system activates more frequently and for longer periods than is necessary, like revving a car engine for hours every day. This wear and tear increases the risk of stress-related physical and mental illness later in life." (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2005/2014)

"Although they are necessary for survival, frequent neurobiological stress responses increase the risk of physical and mental health problems, perhaps particularly when experienced during periods of rapid brain development." (Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007)

"Based on these bourgeoning lines of research, it appears that many factors converge during adolescence that may make this stage of development a particularly sensitive period to stressors, particularly in regard to neurobiological processes." (Eiland & Romeo 2013)

Finally, in this section, is the notion 'learning to love'; not just learning to love what you do although that plays a big part in achieving much of the above but, also, adding love and care to your interactions with others:

"I realised that morning that a hospital's number one responsibility should be protecting its patients' energy levels. This young girl was an energy vampire. She wanted to take something from me despite my fragile condition, and she had nothing to give me in return, She was rushing against a clock and obviously losing the race. In her haste, she was rough in the way she handled me and I felt like a detail that had fallen through someone's crack. She spoke a million miles a minute and hollered at me as if I were deaf. I sat and observed her absurdity and ignorance. She was I a hurry and I was a stroke survivor - not a natural match! She might have gotten something more from me had she come to me gently with patience and kindness, but because she insisted that I come to her in her time and at her pace, it was not satisfying for either of us. Her demands were annoying and I felt weary from the encounter." (Bolte Taylor, 2008, page 81)

In the 24th Annual Benjamin Ide Wheeler Society Lecture (2011), Professor Marian Diamond list five factors that her research highlighted as important for the enrichment of brains, one of which was 'love' (the other four will be covered elsewhere on this webpage. However, if you cannot wait to discover what they are watch the lecture yourself on YouTube by following the link above). Diamonds research showed that the love care and attention she payed to the research animals in her care the greater their cerebral cortex:

"She said she stumbled upon the fifth factor while performing her experiments with lab rats, which weren’t living long enough for her to study their brains in old age. Although the cages were well cleaned, many of the rats were dying after about 600 days, or roughly 60 years in a human time span. But some were living much longer. The difference, she found, was touch. By holding the lab rats against her lab coat and petting them each day, she found that she could increase their life span — and found that these rats generally had thicker cerebral cortices."

(Harrison Smith, 2016, The Washington Post, Obituary of Marian Diamond)

In other words, those animals who had more loving care had better developed brains and, thus, she added 'love' as a factor to her talks on the enrichment of the neural structure of the cerebrum.

“Begin at the beginning," the King said, very gravely, "and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

It may seem obvious that, in teaching Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties (IEPMLD), we need to begin at the beginning, carry on until we get to the place we intended for our session, and then stop but what does that actually mean in practice? Where is the beginning? How should we carry on? How do we know that we have reached 'the end'? How do we know that the IEPMLD have made that journey along with us?

"How to make the process meaningful and accessible to children with PMLD and the practicalities of sharing in a transparent manner is practically challenging." (Goodwin, 2013, page 24)

There will have been times in your life when you have been listening intently to an explanation but, as the explanation proceeded, somewhere along the way you lost the plot and failed to grasp what was being said. For example, when listening to theoretical physics at the quantum level I start out comprehending (at least I think I comprehend) what is being said but, as the explanation moves deeper and deeper, I find myself completely confused and not understanding. Can my understanding be improved? Can the structure of my brain be altered such that my intelligence is developed so that I can understand what is being said? Perhaps there are ways of achieving that but isn't there a much, much simpler solution? Rather than improve understanding why don't we improve the teaching? If the message was conveyed in a way which was commensurate with the level of my understanding then perhaps I might be able to move further along the pathway. It is therefore important that the teaching staff are aware of 'considered best practice' and the course that they should follow:

"A handicapped child represents a qualitatively different, unique type of development.... If a blind or deaf child achieves the same level of development as a normal child, then the child with a defect achieves this in another way, by another course, by other means; and, for the pedagogue, it is particularly important to know the uniqueness of the course along which he must lead the child. This uniqueness transforms the minus of the handicap into the plus of compensation." (Vygotsky, 1993)

In teaching IEPMLD we must obey at least eight fundamental rules:

Take the Trouble to start in the right place; that is with what the Learners already know and understand;