Choice Pickings

The Development of Choice Making Skills in

Individuals Experiencing Significant Learning Difficulties:

Theory and Practice

"When you have to make a choice and don't make it, that is in itself a choice."

William James

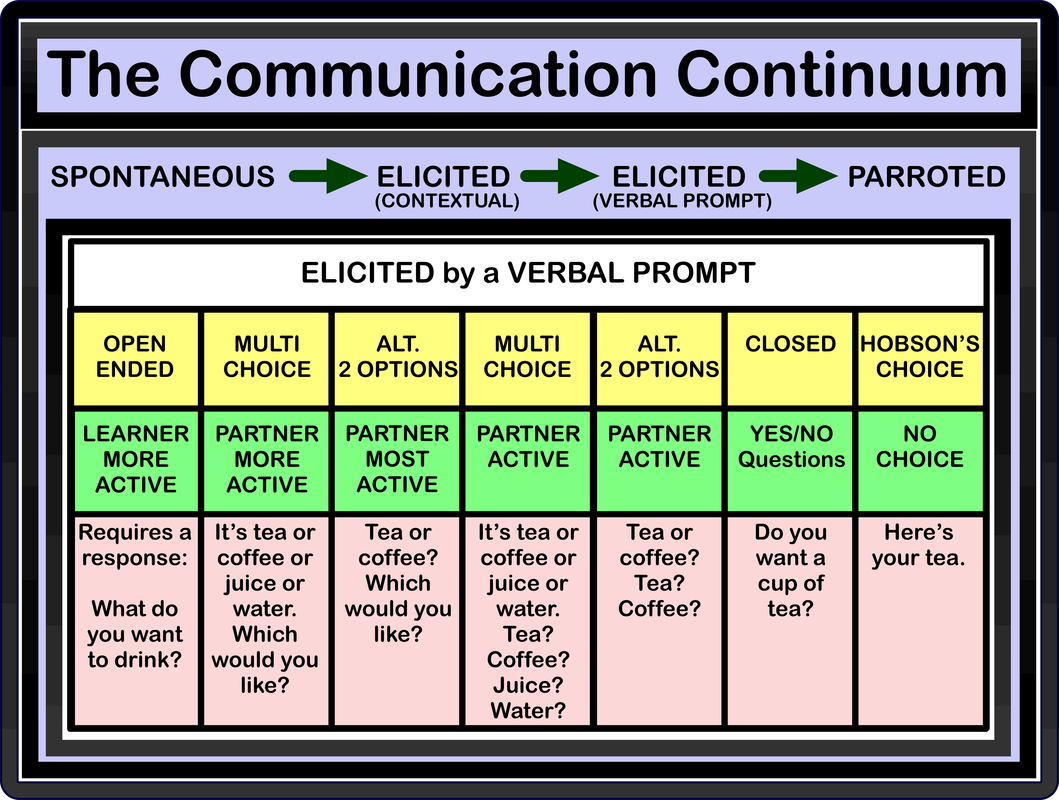

"No previous research has looked specifically at how best to offer choices to people with mental handicaps but several studies have addressed the issue of how to ask questions of people with mental handicaps. the findings suggest that their responses to questions are often restrained by the structure of the question rather than the content. for example, in response to questions requiring a yes/no answer people with a mental handicap tend to respond with a yes (Gerjuoy and Winters 1966; Rosen et al 1974; Sigelman et al 1981)"

(March 1992 page 122)

"People with learning difficulties should be enabled to make informed choices and take reasonable risks."

(Sutcliffe 1990 page 3)

"Self advocacy should be a key component of learning, underpinning the development of a curriculum built on student choice, decision-making and empowerment." (Sutcliffe 1990 page 19)

"Learning should offer maximum opportunities for students to plan for themselves and to make choices and decisions."

(Sutcliffe 1990 page 21)

"It was a common experience for people living in hospital to suffer physical and verbal abuse, be denied choices and rights, and have few educational, social or employment opportunities. Those people who lived in the community fared little better. They too had restricted choices, went to institutionalised day centres and had limited opportunities for employment and education"

(Virginia Moffat 1996 page 13)

"Even in supposedly enlightened community care settings, I have often seen situations where supporters control, intimidate and restrict choices" (Virginia Moffat 1996 page 14)

"The communication needs of children and adults with PMLD are complex. Many children and adults with PMLD have no formal means of communication, such as speech, signs or symbols. They may use a range of non-verbal means such as facial expression and body language, to communicate and be highly reliant on others to interpret these and enable them to be involved in choices and decisions. Because of this, they are often excluded."

PMLD Network Valuing people with Profound and Multiple Learning Disabilities (PMLD) Page 9

"Developing the pupils ability to make choices is an important extension of the capacity for enjoyment. It is a vital achievement on the pathway of achieving autonomy."

(Coupe-O'Kane, Porter & Taylor 1994)

"However, choice making – an important skill for all developing youngsters is even more important for those with PMLD. Error free choices may support the development of understanding. It is only by being offered choices on a very regular basis that the usefulness of being able to make choices will become apparent. Choices can vary between real object, picture or symbol depending on pupil’s need. If objects are used consideration for accompanying the object with a picture and/or symbol is needed in order for the pupil to get the connection and be prepared for moving on."

SCOPE: Supporting Communication through AAC, Module 9

"People with intellectual disability, however, attached greater importance to all aspects of their lives than did people without a disability. This may be linked to their aspirations, preferences, and opportunities for choice, which may, therefore, be a more meaningful way of considering their life quality." (Hensel 2000 page 35)

"We believe that everyone should be able to make choices. This includes people with severe and profound learning disabilities who, with the right help and support, can make important choices and express preferences about their day to day lives."

(Valuing people, Department of Health 2001, Page 24)

"One of the most important things that practitioners can do in their work is to respect the choices that people with disabilities make from the options that are available to them." (Brown and Brown 2003 Page 222)

"Many people assume that the presence of an intellectual disability precludes a person from becoming self-determined. Recent research, however, has suggested that the environments in which people live, learn, work or play may play a more important role in promoting self-determination then do personal characteristics of the person, including level of intelligence."

(Wehmeyer & Garner 2003)

"Choice continues to be a major concern for those responsible for service provision to people with learning disabilities and it is one of the cornerstones of Valuing People (Department of Health, 2001). While initial assumptions and instincts might lead one to think otherwise, a substantial body of research suggests that many people with PMLD are able to make choices reliably."

(Carnaby 2004 page 8)

"The main findings in these studies were that choice interventions led to decreases in inappropriate behavior and increases in appropriate behavior, and that various preference assessments could be used to identify reinforcing stimuli."

Cannella, O’Reilly, & Lancioni (2005)

"Choice is often restricted for people with learning difficulties. Food choice is an integral part of our life – it is often an unconscious process that is taken for granted. However, people with intellectual difficulties are often prevented from making choices about food because they do not have the means to do so."

Goodman & Keeton (2005)

"Over the last two decades, an increasing number of authors have advocated for providing individuals with disabilities the right to make choices. The majority of discussions focused on the importance of choice-making opportunities to the overall quality of life for persons with disabilities (see Bannerman, Sheldon, Sherman, & Harchik, 1990, for a discussion). For example, choice can be seen as a means of incorporating the preferences of individuals into their daily home, school, and work environments. Choice also allows clinicians to identify and use the most potent reinforcers, thus enhancing learning and performance. Research has demonstrated that choice may be associated with increases in appropriate behavior, improvements in task performance, and decreases in problem behavior (see Kern et al., 1998, for a review). Furthermore, the right to make choices allows for a more normalized lifestyle and thus should be a goal of all who serve individuals with disabilities."

Vorndran (2005)

"One of the most basic building blocks leading to enhanced self-determination is the ability to make informed choices for opportunities within one’s daily life. Considering the skills involved in becoming self-determined, choice making is one of the first and most basic skills to develop and build upon."

Wolf, J., & Joannou, K. (2012)

"Training and education must be provided to persons with ID in order to help them develop better decision-making skills."

Werner, S. (2012 Page 23)

"Best and recommended practices now highlight the importance of providing students with disabilities with meaningful opportunities to develop the skills, attitudes, and behaviors that can enhance their self-determination."

Lane, Carter, & Sisco (2012 page 238)

"Choice constitutes a core element of the human experience. To deny this right can be seen as a denial of basic human rights and yet for people with learning disabilities this has often been a reality. Some argue that choice is different for people with learning disabilities for a variety of intellectually based reasons. The effect of choice on people with learning disabilities therefore is an important area of concern for researchers to establish the underlying meaning and drivers for increasing choice for this group of people." (Bradley 2012)

"The choices we make define who we are. People with learning disabilities have often had been denied a diverse range of choices, from small day-to-day to significant health care decisions. Empowering people contributes to an enhanced dignified experience of health care."

Royal College of Nursing (2013 Page 12)

"Research supports the idea that almost all people are capable of purposeful choice making if they are provided with a functional way of doing so that accurately interprets their behavior (Agran et al., 2010; Lancioni et al, 1996; Snell & Brown, 2011)."

( Littrell S. 2013 page 3)

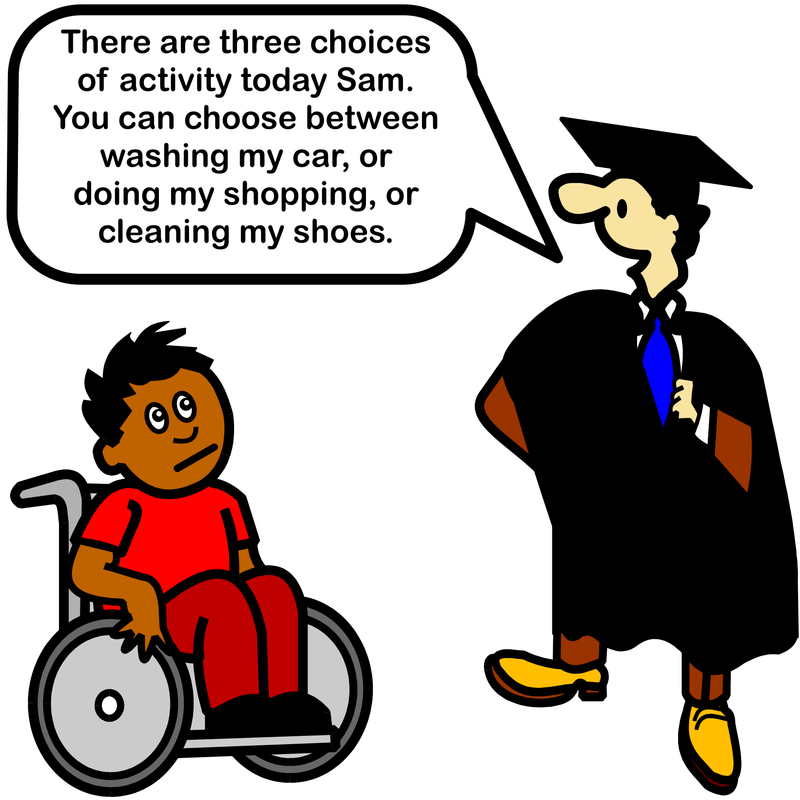

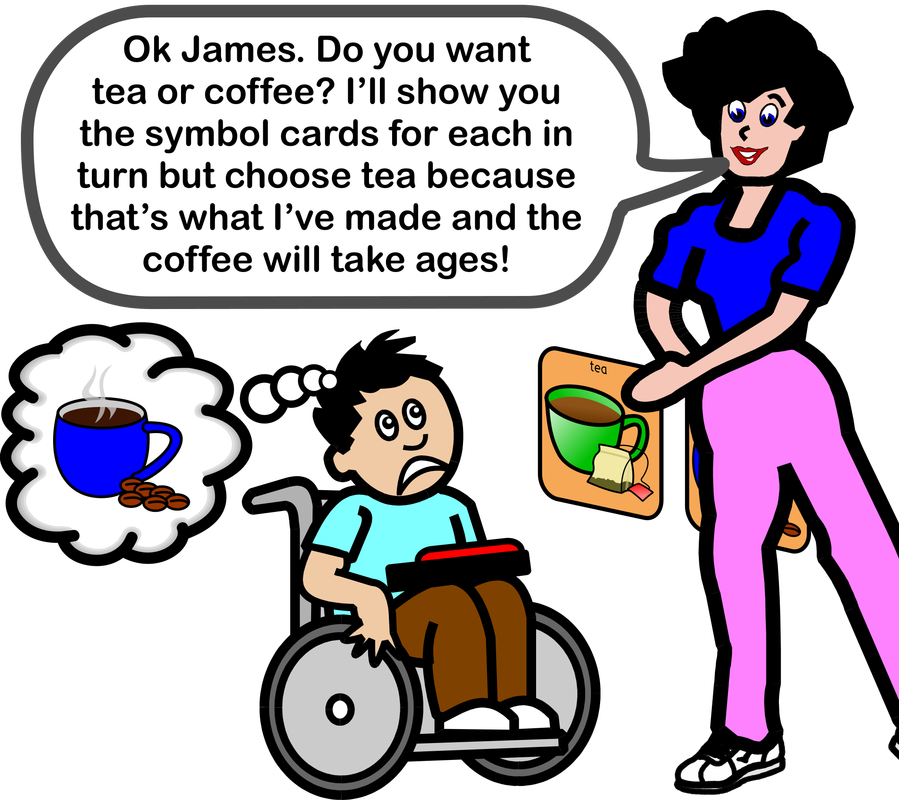

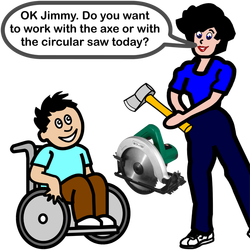

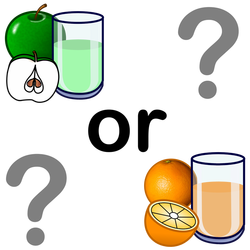

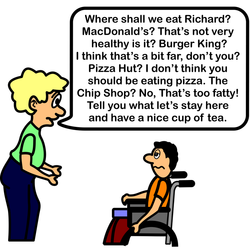

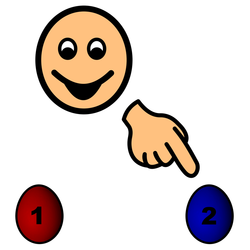

The 'provision of an opportunity to make an uncoerced selection from two or more alternatives' is perhaps how people might define the delivery of choice to individual Learners within Special Education. This web page is devoted to an exploration of the concept of the provision of choice for Individuals Experiencing Learning Difficulties (IELD). While few would argue that the notion of giving IELD as much choice in (and, thus, more control over) their life is a bad thing, every form of practice in this area cannot be considered as good. Indeed, as this page will attempt to show, some of what is proffered as choice making activity in our educational establishments (and beyond) might be considered questionable practice.

Although we all make hundreds of basic choices every day (from what to eat, and drink, to what to do, wear and watch), in the past, Individuals Experiencing Learning Difficulties were provided with almost no opportunities to make choices (See Bambara & Koger, 1996; Kearney, Bergan, & McKnight, 1998; Stancliffe & Abery, 1997; Stancliffe & Wehmeyer, 1995). While it might be argued that this issue is a problem that was related to the past, a recent report (Bradshaw, J. Beadle-Brown, J., Beecham J., Mansell, J., Baumker, T., Leigh, J., Whelton, R., & Richardson, L. 2013) showed that (page 25) on average people with an Intellectual Disability:

Lancioni, O’Reilly, & Emerson, (1996) showed that individuals with profound developmental disabilities can make choices and Browder, Cooper, & Lim (1998) showed that supporting staff are able to learn to provide more choice within the daily routine. The benefits of such increase in the level of choice provision include:

specific, objectively measured problem behaviors." (Dyer, Dunlap, & Winterling, 1990 page 519)

Thus, the provision of choice for IELD is, in theory at least, as evidenced by the research, a very good thing to do. However, how we choose to provide choice and what we assume in response to the choices seemingly made by individual Learners can be problematic. What exactly is choice? Is choice a good thing? Can there be too much choice? How should choice be provided? How can you be certain that an Individual has made a choice? These and other questions are addressed on this page.

As with many other pages on this web site, a contact form is provided at the bottom of the this page such that you can make comments, give your opinions, agree or disagree, ask questions, seek further information, point out errors, and the like. If you disagree with some of the items on this page, I hope, at the very least, they will make you reflect on your current practice...

This webpage was last updated on:

26th February 2015.

As the page is updated further, I will update this counter such that you will be aware if any further information has been added.

William James

"No previous research has looked specifically at how best to offer choices to people with mental handicaps but several studies have addressed the issue of how to ask questions of people with mental handicaps. the findings suggest that their responses to questions are often restrained by the structure of the question rather than the content. for example, in response to questions requiring a yes/no answer people with a mental handicap tend to respond with a yes (Gerjuoy and Winters 1966; Rosen et al 1974; Sigelman et al 1981)"

(March 1992 page 122)

"People with learning difficulties should be enabled to make informed choices and take reasonable risks."

(Sutcliffe 1990 page 3)

"Self advocacy should be a key component of learning, underpinning the development of a curriculum built on student choice, decision-making and empowerment." (Sutcliffe 1990 page 19)

"Learning should offer maximum opportunities for students to plan for themselves and to make choices and decisions."

(Sutcliffe 1990 page 21)

"It was a common experience for people living in hospital to suffer physical and verbal abuse, be denied choices and rights, and have few educational, social or employment opportunities. Those people who lived in the community fared little better. They too had restricted choices, went to institutionalised day centres and had limited opportunities for employment and education"

(Virginia Moffat 1996 page 13)

"Even in supposedly enlightened community care settings, I have often seen situations where supporters control, intimidate and restrict choices" (Virginia Moffat 1996 page 14)

"The communication needs of children and adults with PMLD are complex. Many children and adults with PMLD have no formal means of communication, such as speech, signs or symbols. They may use a range of non-verbal means such as facial expression and body language, to communicate and be highly reliant on others to interpret these and enable them to be involved in choices and decisions. Because of this, they are often excluded."

PMLD Network Valuing people with Profound and Multiple Learning Disabilities (PMLD) Page 9

"Developing the pupils ability to make choices is an important extension of the capacity for enjoyment. It is a vital achievement on the pathway of achieving autonomy."

(Coupe-O'Kane, Porter & Taylor 1994)

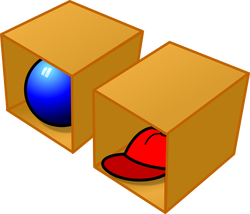

"However, choice making – an important skill for all developing youngsters is even more important for those with PMLD. Error free choices may support the development of understanding. It is only by being offered choices on a very regular basis that the usefulness of being able to make choices will become apparent. Choices can vary between real object, picture or symbol depending on pupil’s need. If objects are used consideration for accompanying the object with a picture and/or symbol is needed in order for the pupil to get the connection and be prepared for moving on."

SCOPE: Supporting Communication through AAC, Module 9

"People with intellectual disability, however, attached greater importance to all aspects of their lives than did people without a disability. This may be linked to their aspirations, preferences, and opportunities for choice, which may, therefore, be a more meaningful way of considering their life quality." (Hensel 2000 page 35)

"We believe that everyone should be able to make choices. This includes people with severe and profound learning disabilities who, with the right help and support, can make important choices and express preferences about their day to day lives."

(Valuing people, Department of Health 2001, Page 24)

"One of the most important things that practitioners can do in their work is to respect the choices that people with disabilities make from the options that are available to them." (Brown and Brown 2003 Page 222)

"Many people assume that the presence of an intellectual disability precludes a person from becoming self-determined. Recent research, however, has suggested that the environments in which people live, learn, work or play may play a more important role in promoting self-determination then do personal characteristics of the person, including level of intelligence."

(Wehmeyer & Garner 2003)

"Choice continues to be a major concern for those responsible for service provision to people with learning disabilities and it is one of the cornerstones of Valuing People (Department of Health, 2001). While initial assumptions and instincts might lead one to think otherwise, a substantial body of research suggests that many people with PMLD are able to make choices reliably."

(Carnaby 2004 page 8)

"The main findings in these studies were that choice interventions led to decreases in inappropriate behavior and increases in appropriate behavior, and that various preference assessments could be used to identify reinforcing stimuli."

Cannella, O’Reilly, & Lancioni (2005)

"Choice is often restricted for people with learning difficulties. Food choice is an integral part of our life – it is often an unconscious process that is taken for granted. However, people with intellectual difficulties are often prevented from making choices about food because they do not have the means to do so."

Goodman & Keeton (2005)

"Over the last two decades, an increasing number of authors have advocated for providing individuals with disabilities the right to make choices. The majority of discussions focused on the importance of choice-making opportunities to the overall quality of life for persons with disabilities (see Bannerman, Sheldon, Sherman, & Harchik, 1990, for a discussion). For example, choice can be seen as a means of incorporating the preferences of individuals into their daily home, school, and work environments. Choice also allows clinicians to identify and use the most potent reinforcers, thus enhancing learning and performance. Research has demonstrated that choice may be associated with increases in appropriate behavior, improvements in task performance, and decreases in problem behavior (see Kern et al., 1998, for a review). Furthermore, the right to make choices allows for a more normalized lifestyle and thus should be a goal of all who serve individuals with disabilities."

Vorndran (2005)

"One of the most basic building blocks leading to enhanced self-determination is the ability to make informed choices for opportunities within one’s daily life. Considering the skills involved in becoming self-determined, choice making is one of the first and most basic skills to develop and build upon."

Wolf, J., & Joannou, K. (2012)

"Training and education must be provided to persons with ID in order to help them develop better decision-making skills."

Werner, S. (2012 Page 23)

"Best and recommended practices now highlight the importance of providing students with disabilities with meaningful opportunities to develop the skills, attitudes, and behaviors that can enhance their self-determination."

Lane, Carter, & Sisco (2012 page 238)

"Choice constitutes a core element of the human experience. To deny this right can be seen as a denial of basic human rights and yet for people with learning disabilities this has often been a reality. Some argue that choice is different for people with learning disabilities for a variety of intellectually based reasons. The effect of choice on people with learning disabilities therefore is an important area of concern for researchers to establish the underlying meaning and drivers for increasing choice for this group of people." (Bradley 2012)

"The choices we make define who we are. People with learning disabilities have often had been denied a diverse range of choices, from small day-to-day to significant health care decisions. Empowering people contributes to an enhanced dignified experience of health care."

Royal College of Nursing (2013 Page 12)

"Research supports the idea that almost all people are capable of purposeful choice making if they are provided with a functional way of doing so that accurately interprets their behavior (Agran et al., 2010; Lancioni et al, 1996; Snell & Brown, 2011)."

( Littrell S. 2013 page 3)

The 'provision of an opportunity to make an uncoerced selection from two or more alternatives' is perhaps how people might define the delivery of choice to individual Learners within Special Education. This web page is devoted to an exploration of the concept of the provision of choice for Individuals Experiencing Learning Difficulties (IELD). While few would argue that the notion of giving IELD as much choice in (and, thus, more control over) their life is a bad thing, every form of practice in this area cannot be considered as good. Indeed, as this page will attempt to show, some of what is proffered as choice making activity in our educational establishments (and beyond) might be considered questionable practice.

Although we all make hundreds of basic choices every day (from what to eat, and drink, to what to do, wear and watch), in the past, Individuals Experiencing Learning Difficulties were provided with almost no opportunities to make choices (See Bambara & Koger, 1996; Kearney, Bergan, & McKnight, 1998; Stancliffe & Abery, 1997; Stancliffe & Wehmeyer, 1995). While it might be argued that this issue is a problem that was related to the past, a recent report (Bradshaw, J. Beadle-Brown, J., Beecham J., Mansell, J., Baumker, T., Leigh, J., Whelton, R., & Richardson, L. 2013) showed that (page 25) on average people with an Intellectual Disability:

- were engaged in activity for less than half the time (44%);

- had little contact from staff for around 75% of the time;

- received direct assistance to partake in activities for only 6% of the time;

- typically had little support for choice with 22% getting what they considered to be good support in this area.

Lancioni, O’Reilly, & Emerson, (1996) showed that individuals with profound developmental disabilities can make choices and Browder, Cooper, & Lim (1998) showed that supporting staff are able to learn to provide more choice within the daily routine. The benefits of such increase in the level of choice provision include:

- an increase in the dignity of the individual Learner (Perske 1972);

- a reduction in behaviours that staff may find challenging (Dyer, Dunlap, & Winterling, 1990; Carr & Carlson, 1993; Lindauer, Deleon, & Fisher 1999, Lohrmann-O’Rourke & Yurman, 2001);

specific, objectively measured problem behaviors." (Dyer, Dunlap, & Winterling, 1990 page 519)

- an improved staff awareness of preferences of individual Learners (Browder et al; 1998);

- a continuing increase in number of choice opportunities offered by staff (Cooper and Browder (2001);

- an increase in the the engagement of the Learner in the task (Dunlap et al., 1994, Cole & Levinson, 2002);

- the development of early communication skills (Stephenson & Linfoot, 1995);

- an increase in spontaneous speech production where physically possible (Dyer, 1987);

- an improvement in student performance on curricular materials and interventions (Cole & Levinson, 2002)

- a higher quality of life outcomes (Willis, Grace, & Roy, 2008, Stancliffe et al., 2011);

- a higher scores on quality of life indicators (Neely-Barnes, Marcenko, & Weber, 2008);

- an increase in social interaction with general education peers (Kennedy & Haring, 1993).

Thus, the provision of choice for IELD is, in theory at least, as evidenced by the research, a very good thing to do. However, how we choose to provide choice and what we assume in response to the choices seemingly made by individual Learners can be problematic. What exactly is choice? Is choice a good thing? Can there be too much choice? How should choice be provided? How can you be certain that an Individual has made a choice? These and other questions are addressed on this page.

As with many other pages on this web site, a contact form is provided at the bottom of the this page such that you can make comments, give your opinions, agree or disagree, ask questions, seek further information, point out errors, and the like. If you disagree with some of the items on this page, I hope, at the very least, they will make you reflect on your current practice...

This webpage was last updated on:

26th February 2015.

As the page is updated further, I will update this counter such that you will be aware if any further information has been added.

Too much of a good thing?

"Sometimes too much choice can be confusing." (Jackson & Jackson 1999 page 81)

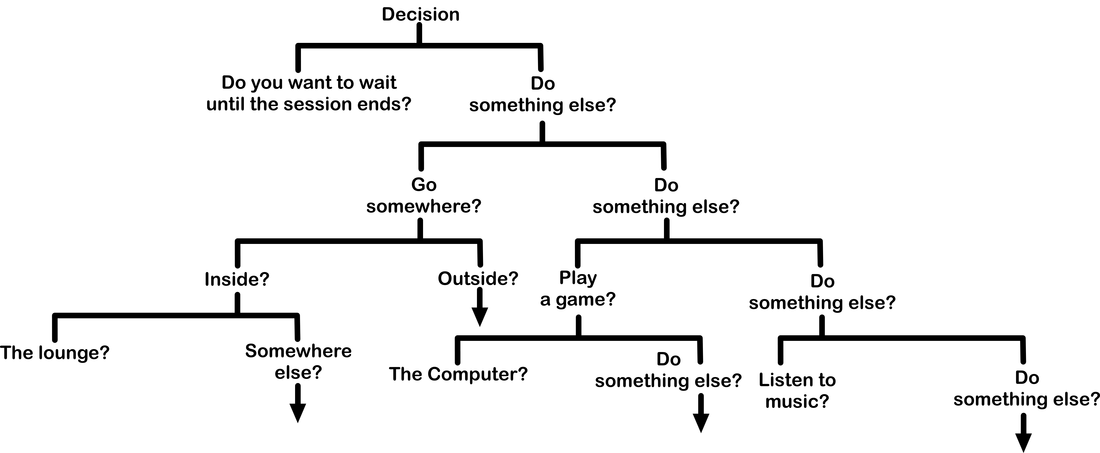

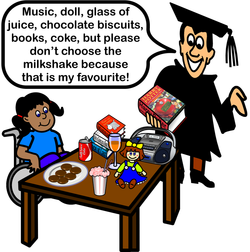

While the provision of choice throughout the day is undoubtedly a good thing, too much of anything may itself be problematic. Learners (indeed, any of us) may become overwhelmed or stressed if presented with too much choice at any one time (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven, & Tice1998; Iyengar & Lepper, 2000; Schwartz, 2000).

While the provision of choice throughout the day is undoubtedly a good thing, too much of anything may itself be problematic. Learners (indeed, any of us) may become overwhelmed or stressed if presented with too much choice at any one time (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven, & Tice1998; Iyengar & Lepper, 2000; Schwartz, 2000).

Thus, while the ability to make choices during the day should not be restricted, it might be wise not to overburden the Learner with too much choice at any one time. Of course, that assertion itself is problematic! If choice is to be limited at any one time:

- who is decide on what options are to be made available?

- why did they decide on these?

- how are they to decide?

- are these decisions, once made, fixed?

- what if the Learner does not want any of them?

The Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities 2008

United Nations

United Nations

"The basic human right to choice is mandatory according to the CRPD which was adopted by the United Nations in 2006 and came into force internationally in 2008. To date, 153 nations have signed the Convention and 119 have ratified it. Ratifying nations commit themselves to implement all obligations of the Convention. The CRPD is the first disability-specific international treaty and the first treaty to adopt the human rights approach to disability. Specifically, the CRPD promotes freedom of choice and autonomy, non-discrimination, full participation and inclusiveness in society, respect for the differences evident in persons with disabilities, equality of opportunity, accessibility to core social goods and services, and the identification and removal of barriers."

(Werner, S. 2012. Page 3)

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities came into force in 2008. It has been signed and ratified by 119 nations including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom but, although signed, it has still not been ratified by the USA or Ireland.

(Werner, S. 2012. Page 3)

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities came into force in 2008. It has been signed and ratified by 119 nations including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom but, although signed, it has still not been ratified by the USA or Ireland.

|

In the UK, the CRPD builds further on the MCA (Mental Capacity Act 2005) which came into force in 2007:

"The Mental Capacity Act 2005 is the first piece of legislation to clearly state that people can no longer make decisions on behalf of others without following a process." (Fulton, Woodley, & Sanderson 2008 page 5) Many other countries have similar legislation. This means that choice is not just a right, it is the law and we all need to understand what is considered best practice in this area. The MCA is governed by five core principles:

|

- Right to make unwise decisions. Learners have a right to make decisions others may think are not wise. Just because others may think a decision is unwise does not mean that the Learner is incapable of making a decision

- Best interests. Any act of substituted decision-making must be in the best interest of the Learner. That is, if someone other than the Learner makes a decision on his or her part, it must be in their best interest.

- Least restrictive option. Any substituted decision made should be the least restrictive option possible for the Learner..

The SEN Code Of Practice 2014 came into force in September 2014. It made several changes to structure including continuing to put the Learner at the centre of planning and provision. Among a whole raft of recommendations and requirements it states:

1.2 These principles are designed to support:

- the participation of children, their parents and young people in decision- making;

- greater choice and control for young people and parents over support.

1.3 Local authorities must ensure that children, their parents and young people are involved in discussions and decisions about their individual support and about local provision.

1.6 Children have a right to receive and impart information, to express an opinion and to have that opinion taken into account in any matters affecting them from the early years.

1.39 Independent living – enabling people to have choice and control over their lives and the support they receive, their accommodation and living arrangements, including supported living

1.40 All professionals working with families should look to enable children and young people to make choices for themselves from an early age and support them in making friends and staying safe and healthy.

8.15 As young people develop, and increasingly form their own views, they should be involved more and more closely in decisions about their own future.

The Code also makes specific reference to the Mental Capacity Act 2005 in dealing with advocacy issues. As you can see, Learner choice and control are among the fundamental features of the code.

1.2 These principles are designed to support:

- the participation of children, their parents and young people in decision- making;

- greater choice and control for young people and parents over support.

1.3 Local authorities must ensure that children, their parents and young people are involved in discussions and decisions about their individual support and about local provision.

1.6 Children have a right to receive and impart information, to express an opinion and to have that opinion taken into account in any matters affecting them from the early years.

1.39 Independent living – enabling people to have choice and control over their lives and the support they receive, their accommodation and living arrangements, including supported living

1.40 All professionals working with families should look to enable children and young people to make choices for themselves from an early age and support them in making friends and staying safe and healthy.

8.15 As young people develop, and increasingly form their own views, they should be involved more and more closely in decisions about their own future.

The Code also makes specific reference to the Mental Capacity Act 2005 in dealing with advocacy issues. As you can see, Learner choice and control are among the fundamental features of the code.

What is choice?

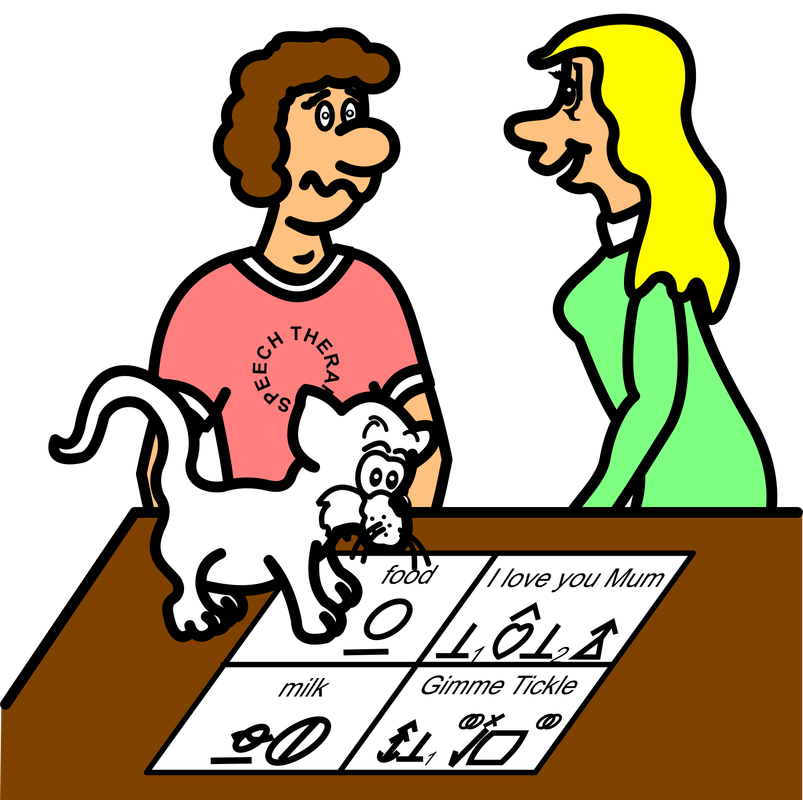

While this might, at first glance, seem like a rather strange question to ask at this point on this webpage, it is more difficult to answer than one might expect. Try to define the word choice without using either any form of the the word 'choice' itself (choose, chosen, choosing, choices ...) or any synonym for the word 'choice' (for example without using word such as: decide, determine which, elect, opt, pick, prefer, select, …). It's not so easy is it? Look up choice or choose within the available web dictionaries and they all fall into this trap of stating that Choice is 'choosing between alternatives', 'the selection between two or more options', 'deciding between presented alternatives'. What we thus have is something of a tautology - choice is choosing!

Did you manage to define choice without using a synonym for choice in the definition? It's not easy! It's perhaps even more complex when we consider what choice means for those Individuals Experiencing PMLD.

For the present, Talksense will define choice as:

"The independent knowledge (understanding, consciousness) that a particular behaviour (action, vocalisation, physical movement, indicating strategy) will lead to (result in, be commensurate with) a specific (desired) result (goal, need fulfillment, attainment) when presented with a set of recognised (known, comprehended), whole (not selecting for a part of or an attribute of), alternatives at a particular point in time."

Here choice is regarded as a specific observable independent behaviour which has a particular consequence in response to a given range of currently available alternate stimuli. The notion of individual consciousness of the behaviour plays an important role in all aspects of this. The Learner has to be conscious of the:

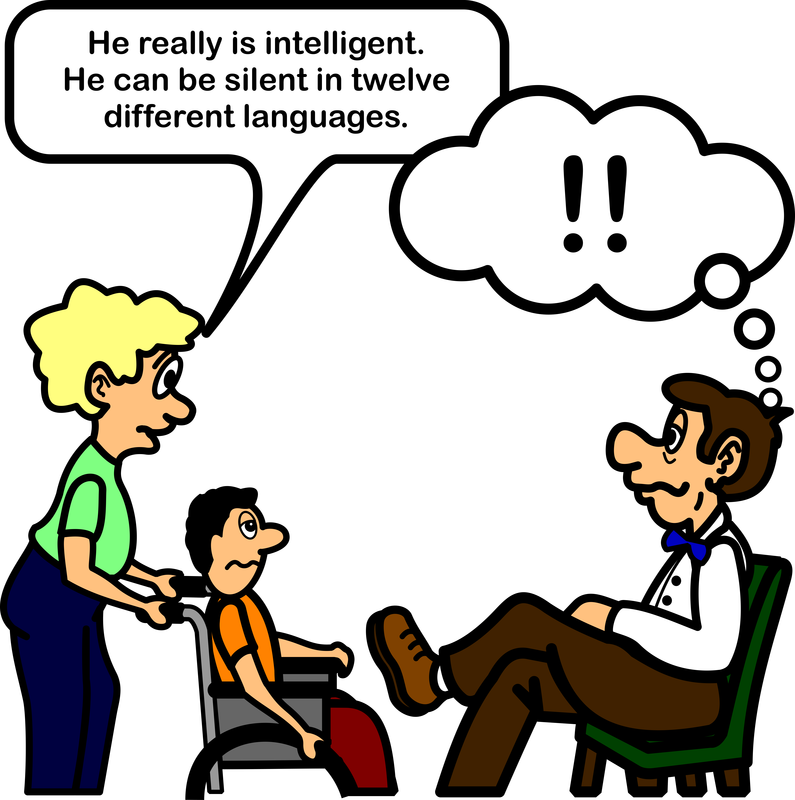

All of this from an individual whose understanding of the world is limited as a result of his/her condition. The Learner therefore has to be conscious of the situation, each of the alternatives, what is being (t)asked of him/her, his/her response strategy, others understanding of his/her response strategy (theory of mind). Is this really feasible from an Individual Experiencing PMLD?

When a staff member states that a particular individual has 'made a choice' are they really implying all of the above? Are they aware of all of the above and does anyone ever ask them to qualify their statement? What they are likely to be stating is that a Learner appeared to indicate (in some manner appropriate to the Learner's physical abilities) an item from a range of other items. However, is this a choice?

Note that the definition makes reference to 'whole' as opposed to 'part of' or 'attribute of'. Imagine a choice of two items being present to a Learner. the Learner s attracted to an attribute of one of the items (colour, luminosity, shape, ...) and therefore looks at it (even Learners registered as 'blind' may be able to 'see' an item if it is illuminated more than another by sunlight for example) and then staff taken this (assuming it) to be a conscious choice made by said individual. Is it a choice? No! The individual has just responded to a feature of an item in a particular manner (exhibiting a specific behaviour) and the response has been read as a choice by others.

Knowing what choice means (having a definition) is a way of deciding what issues need to be addressed in teaching Learners to make choices. The clearer the definition the clearer the pathway to the goal.

Did you manage to define choice without using a synonym for choice in the definition? It's not easy! It's perhaps even more complex when we consider what choice means for those Individuals Experiencing PMLD.

For the present, Talksense will define choice as:

"The independent knowledge (understanding, consciousness) that a particular behaviour (action, vocalisation, physical movement, indicating strategy) will lead to (result in, be commensurate with) a specific (desired) result (goal, need fulfillment, attainment) when presented with a set of recognised (known, comprehended), whole (not selecting for a part of or an attribute of), alternatives at a particular point in time."

Here choice is regarded as a specific observable independent behaviour which has a particular consequence in response to a given range of currently available alternate stimuli. The notion of individual consciousness of the behaviour plays an important role in all aspects of this. The Learner has to be conscious of the:

- stimuli (alternatives);

- the situation (that a specific action on his/her part will result in one particular response. The other alternative will no longer be available);

- his/her behaviour and how it will effect an outcome.

All of this from an individual whose understanding of the world is limited as a result of his/her condition. The Learner therefore has to be conscious of the situation, each of the alternatives, what is being (t)asked of him/her, his/her response strategy, others understanding of his/her response strategy (theory of mind). Is this really feasible from an Individual Experiencing PMLD?

When a staff member states that a particular individual has 'made a choice' are they really implying all of the above? Are they aware of all of the above and does anyone ever ask them to qualify their statement? What they are likely to be stating is that a Learner appeared to indicate (in some manner appropriate to the Learner's physical abilities) an item from a range of other items. However, is this a choice?

Note that the definition makes reference to 'whole' as opposed to 'part of' or 'attribute of'. Imagine a choice of two items being present to a Learner. the Learner s attracted to an attribute of one of the items (colour, luminosity, shape, ...) and therefore looks at it (even Learners registered as 'blind' may be able to 'see' an item if it is illuminated more than another by sunlight for example) and then staff taken this (assuming it) to be a conscious choice made by said individual. Is it a choice? No! The individual has just responded to a feature of an item in a particular manner (exhibiting a specific behaviour) and the response has been read as a choice by others.

Knowing what choice means (having a definition) is a way of deciding what issues need to be addressed in teaching Learners to make choices. The clearer the definition the clearer the pathway to the goal.

The Goal is Control

"There is a real danger that any sense of the identity of a person with learning difficulties is subsumed beneath a prevailing desire to label, to pigeon-hole, to file and thereby to control."

(Gray and Ridden 1999)

"People with disabilities are more visible and more vocal than ever before, and they are increasingly demanding more control and choice in their lives."

(Field, Martin, Miller, Ward, & Wehmeyer 1998 page 11)

"Students become empowered by taking control of their own learning." (Sutcliffe 1990 page 13)

"Good quality support is to do with giving people power."

(Virginia Moffat 1996 page 37)

"a high quality of life is one in which people receive individually tailored support to become full participants in the life of the community, develop skills and independence, be given appropriate choice and control over their lives, be treated with respect in a safe and secure environment”. (Emerson et al 1996)

"Empowerment occurs when control, or power, is passed to an individual or group. In rehabilitation, medicine, social work, psychology, education, and many allied disciplines, it is gradually becoming recognized that the healthiest and most effective individuals have personal control and make decisions for themselves with advice and input from others. The belief here is that, for best results overall, final decisions should be made by the individuals who are most closely affected by the decisions." (Brown and Brown 2003 page 227)

"Choice can be viewed as a key component of empowerment where individuals maintain control over their own lives and as such increase their ability to influence their future goals and ideals." (Bradley 2012)

Generally speaking, the more independent people are and the less external control they receive from others, the more satisfied they are (higher quality of life) (See Legault 1992).Thus, a fundamental goal of all special education should be equipping Learners to live as independent a life as possible. This has long been recognised:

"... citizens with a mental retardation have a right to receive such individual habilitation as will give each of them a realistic opportunity to lead a more useful and meaningful life and to return to society." (Bannerman, Sheldon, Sherman, & Harchik 1990)

"even children with profound learning difficulties , given suitable conditions provided by modern technology, can make choices; in this case between sounds, voices, and rhymes provided on speakers. Moreover, they show enjoyment while so occupied and are motivated to further choice making. At the beginning of this chapter, the opinion was expressed that every step on the way to having more control over our lives is worth taking. In the case of these children, opportunity to exert control, however limited, appears to be leading to increased motivation and increasing self-regulation." (Beryl Smith 1994)(Page 5)

In order to meet this goal, staff within special education should be developing ways in which more and more control can be passed to Learners. Staff should rarely ever be doing it 'for' (there are some exceptions to this rule) and should hardly ever be doing it 'with' (again with some exceptions) but, rather, be facilitating individuals to do it for themselves. The goal of control therefore is one in which choice is not just permitted at certain points at the dictate of others but one which is a fundamental and integral part of the day:

"Our profession has focused on choice-making as a permissible activity, rather than as a teaching target" (Shevin and Klein 1984, page 60)

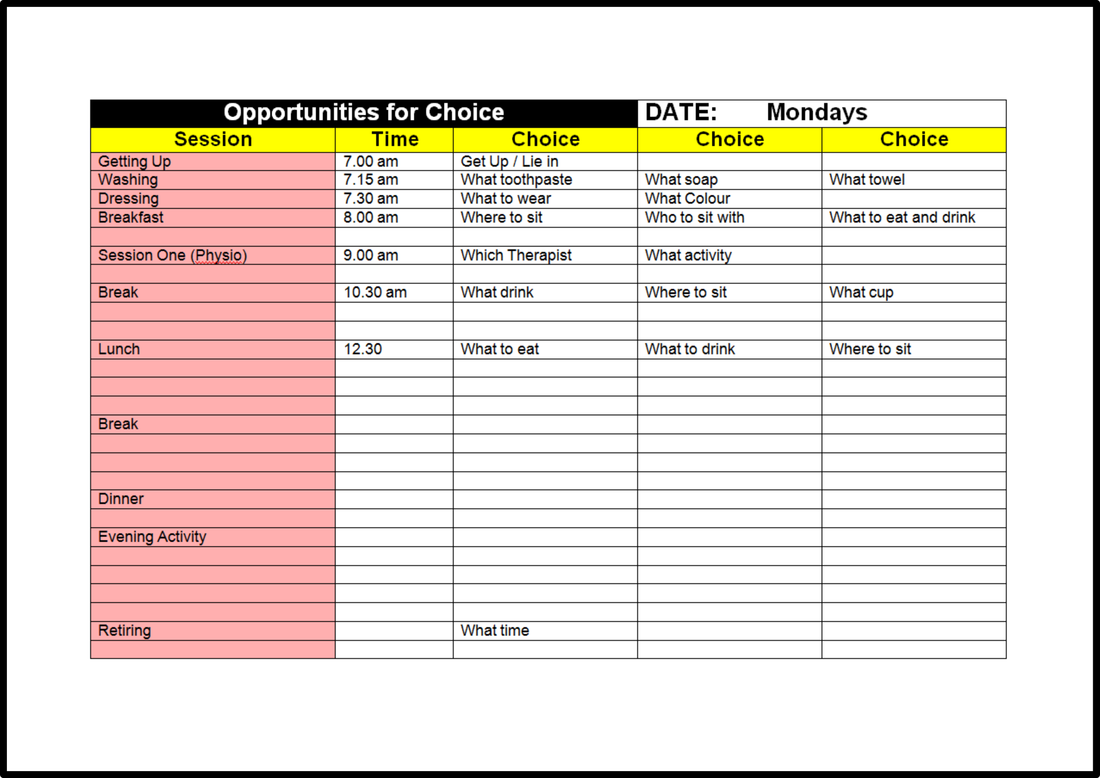

However, while we may find a philosophical commitment to a particular idea or an approach fairly easy, often it is much more difficult to make that approach a reality. For example, to make any establishment (which caters for people with cognitive and physical disabilities) run smoothly, there has to be some sort of ordering and scheduling to accommodate staff coming and going. Such scheduling may impact on the ability to offer free choice at all times of the day to every member of that community: Johnny cannot simply go swimming when he wants to because the pragmatics of the situation do not allow it, any more than they allow me to do anything I want when I want to do it (although it would be nice!). The logical outcome of this apparent dichotomy might be a balance between the demands of the establishment and the needs of the individual for freedom of choice and control. Inflexibility in timetabling and structures lead to a reduction in the opportunities for real choice:

"Inflexible scheduling often precludes opportunities for choice. For instance, clients may not be allowed to choose the order or timing of activities. They may be discouraged from taking breaks or from choosing activities that are not scheduled." (Bannerman, Sheldon, Sherman, & Harchik 1990)

and, at the same time, complete freedom of choice at all times of the day and night would pose insurmountable problems for those with the duty of care. While a balance must be struck, we must keep in mind that the 'goal is control': not the institutional control of the Learners (leading to passivity and learned helplessness) but the Learners control of their lives and their destinies.

Passivity is commonplace amongst people with a severe communication impairment. In a study by Sweeney (Sweeney L. 1991) 42 out of 50 users of AAC showed some level of learned helplessness when interacting with one or more Significant Others. The more severe the communication impairment the greater the degree of helplessness. It would appear that, the development of an individual’s ability to communicate also effects an improvement in an individual’s desire to act independently. The factors that are involved in creating an atmosphere that is supportive of communication are also the factors that tend to demand more interactive skills of an individual. The relationship is reciprocal: greater communicative ability may lead to greater independence and greater independence may lead to greater communicative ability. Prevention is better than cure: the role of communication in the avoidance of personal passivity should be stressed:

"Without an effective means of communication during childhood development of autonomy, exploratory/experiential opportunity, and relative strength of self-image/esteem will be compromised" (Sweeney L. 1993)

While it has been shown that the act of providing real time choices helps with the development of early communication skills (Stephenson & Linfoot, 1995), I want to go further and state that 'choice is a voice'. This notion will be developed further in one of the sections to follow. Of course, offering a choice to a Learner does not mean that they are in control:

"Offering someone a choice does not mean that you are relinquishing control to that person. You are teaching independence."

(Rowland and Schweigert 2000 Page 15)

Indeed, the majority of choices offered in educational establishments are 'contained' (see next section below); that is the choices offered are decided by another (staff member) and not by the Learner her/himself. However, for me, the goal is eventually to hand over control to the Learner (with staff acting as facilitators) with the provisoes that:

(Gray and Ridden 1999)

"People with disabilities are more visible and more vocal than ever before, and they are increasingly demanding more control and choice in their lives."

(Field, Martin, Miller, Ward, & Wehmeyer 1998 page 11)

"Students become empowered by taking control of their own learning." (Sutcliffe 1990 page 13)

"Good quality support is to do with giving people power."

(Virginia Moffat 1996 page 37)

"a high quality of life is one in which people receive individually tailored support to become full participants in the life of the community, develop skills and independence, be given appropriate choice and control over their lives, be treated with respect in a safe and secure environment”. (Emerson et al 1996)

"Empowerment occurs when control, or power, is passed to an individual or group. In rehabilitation, medicine, social work, psychology, education, and many allied disciplines, it is gradually becoming recognized that the healthiest and most effective individuals have personal control and make decisions for themselves with advice and input from others. The belief here is that, for best results overall, final decisions should be made by the individuals who are most closely affected by the decisions." (Brown and Brown 2003 page 227)

"Choice can be viewed as a key component of empowerment where individuals maintain control over their own lives and as such increase their ability to influence their future goals and ideals." (Bradley 2012)

Generally speaking, the more independent people are and the less external control they receive from others, the more satisfied they are (higher quality of life) (See Legault 1992).Thus, a fundamental goal of all special education should be equipping Learners to live as independent a life as possible. This has long been recognised:

"... citizens with a mental retardation have a right to receive such individual habilitation as will give each of them a realistic opportunity to lead a more useful and meaningful life and to return to society." (Bannerman, Sheldon, Sherman, & Harchik 1990)

"even children with profound learning difficulties , given suitable conditions provided by modern technology, can make choices; in this case between sounds, voices, and rhymes provided on speakers. Moreover, they show enjoyment while so occupied and are motivated to further choice making. At the beginning of this chapter, the opinion was expressed that every step on the way to having more control over our lives is worth taking. In the case of these children, opportunity to exert control, however limited, appears to be leading to increased motivation and increasing self-regulation." (Beryl Smith 1994)(Page 5)

In order to meet this goal, staff within special education should be developing ways in which more and more control can be passed to Learners. Staff should rarely ever be doing it 'for' (there are some exceptions to this rule) and should hardly ever be doing it 'with' (again with some exceptions) but, rather, be facilitating individuals to do it for themselves. The goal of control therefore is one in which choice is not just permitted at certain points at the dictate of others but one which is a fundamental and integral part of the day:

"Our profession has focused on choice-making as a permissible activity, rather than as a teaching target" (Shevin and Klein 1984, page 60)

However, while we may find a philosophical commitment to a particular idea or an approach fairly easy, often it is much more difficult to make that approach a reality. For example, to make any establishment (which caters for people with cognitive and physical disabilities) run smoothly, there has to be some sort of ordering and scheduling to accommodate staff coming and going. Such scheduling may impact on the ability to offer free choice at all times of the day to every member of that community: Johnny cannot simply go swimming when he wants to because the pragmatics of the situation do not allow it, any more than they allow me to do anything I want when I want to do it (although it would be nice!). The logical outcome of this apparent dichotomy might be a balance between the demands of the establishment and the needs of the individual for freedom of choice and control. Inflexibility in timetabling and structures lead to a reduction in the opportunities for real choice:

"Inflexible scheduling often precludes opportunities for choice. For instance, clients may not be allowed to choose the order or timing of activities. They may be discouraged from taking breaks or from choosing activities that are not scheduled." (Bannerman, Sheldon, Sherman, & Harchik 1990)

and, at the same time, complete freedom of choice at all times of the day and night would pose insurmountable problems for those with the duty of care. While a balance must be struck, we must keep in mind that the 'goal is control': not the institutional control of the Learners (leading to passivity and learned helplessness) but the Learners control of their lives and their destinies.

Passivity is commonplace amongst people with a severe communication impairment. In a study by Sweeney (Sweeney L. 1991) 42 out of 50 users of AAC showed some level of learned helplessness when interacting with one or more Significant Others. The more severe the communication impairment the greater the degree of helplessness. It would appear that, the development of an individual’s ability to communicate also effects an improvement in an individual’s desire to act independently. The factors that are involved in creating an atmosphere that is supportive of communication are also the factors that tend to demand more interactive skills of an individual. The relationship is reciprocal: greater communicative ability may lead to greater independence and greater independence may lead to greater communicative ability. Prevention is better than cure: the role of communication in the avoidance of personal passivity should be stressed:

"Without an effective means of communication during childhood development of autonomy, exploratory/experiential opportunity, and relative strength of self-image/esteem will be compromised" (Sweeney L. 1993)

While it has been shown that the act of providing real time choices helps with the development of early communication skills (Stephenson & Linfoot, 1995), I want to go further and state that 'choice is a voice'. This notion will be developed further in one of the sections to follow. Of course, offering a choice to a Learner does not mean that they are in control:

"Offering someone a choice does not mean that you are relinquishing control to that person. You are teaching independence."

(Rowland and Schweigert 2000 Page 15)

Indeed, the majority of choices offered in educational establishments are 'contained' (see next section below); that is the choices offered are decided by another (staff member) and not by the Learner her/himself. However, for me, the goal is eventually to hand over control to the Learner (with staff acting as facilitators) with the provisoes that:

- the Learner comprehends the consequences of control and can take responsibility for it;

- the choice is safe.

Prerequisite Factors

click to enlarge

click to enlarge

It is always concerning when I read articles on Significant Learning Difficulties that state prerequisite factors. Of course, there are certain things that require physical abilities; riding a push bike typically requires the ability to control and to move your legs, for example. Thus, I do accept that for some things there are some prerequisites. However, for Individuals experiencing PMLD, prerequisites are a barrier to entry to almost every skill; if these Learners have to meet pre-requisites before being taught to make a choice for example, they may never be taught! Staff may just assume that John is not capable because he lacks the necessary prerequisite skills and just choose for him.

"Having a self-concept or a self picture is a pre-requisite for making a choice" (Jackson and Jackson 1999)

While I do not want to devalue the works of the Jacksons and understand the point they are making, I would want to state, once again, that prerequisites can be a barrier to learning: it may only through being given a choice (for example) that a Learner begins to understand what s/he likes. That is, the practice itself may be a tool (indeed, in some cases, the best tool) by which certain pre-requisite factors can be addressed.

Having made that point, the Jacksons quote above should not be simply dismissed: if the Learner understands his/her needs s/he will be better able to make an informed choice. In their story (see Jackson and Jackson 1999), Danny (one of the characters) knows that he has lots of possessions (they are moving into a new home and deciding who should get each of the rooms) and therefore needs to choose the bigger room to get everything in. However, isn't the way we sometimes learn in life through making ill-informed choices? Had Danny chosen a smaller room because he was attracted to its colour, for example, he would have come to understand the consequences of his decision and learned a lesson. If we try to eliminate every risk then progression may not be possible (see the section on risk on this webpage) although, undoubtedly, there may be some risks that are too big.

"Having a self-concept or a self picture is a pre-requisite for making a choice" (Jackson and Jackson 1999)

While I do not want to devalue the works of the Jacksons and understand the point they are making, I would want to state, once again, that prerequisites can be a barrier to learning: it may only through being given a choice (for example) that a Learner begins to understand what s/he likes. That is, the practice itself may be a tool (indeed, in some cases, the best tool) by which certain pre-requisite factors can be addressed.

Having made that point, the Jacksons quote above should not be simply dismissed: if the Learner understands his/her needs s/he will be better able to make an informed choice. In their story (see Jackson and Jackson 1999), Danny (one of the characters) knows that he has lots of possessions (they are moving into a new home and deciding who should get each of the rooms) and therefore needs to choose the bigger room to get everything in. However, isn't the way we sometimes learn in life through making ill-informed choices? Had Danny chosen a smaller room because he was attracted to its colour, for example, he would have come to understand the consequences of his decision and learned a lesson. If we try to eliminate every risk then progression may not be possible (see the section on risk on this webpage) although, undoubtedly, there may be some risks that are too big.

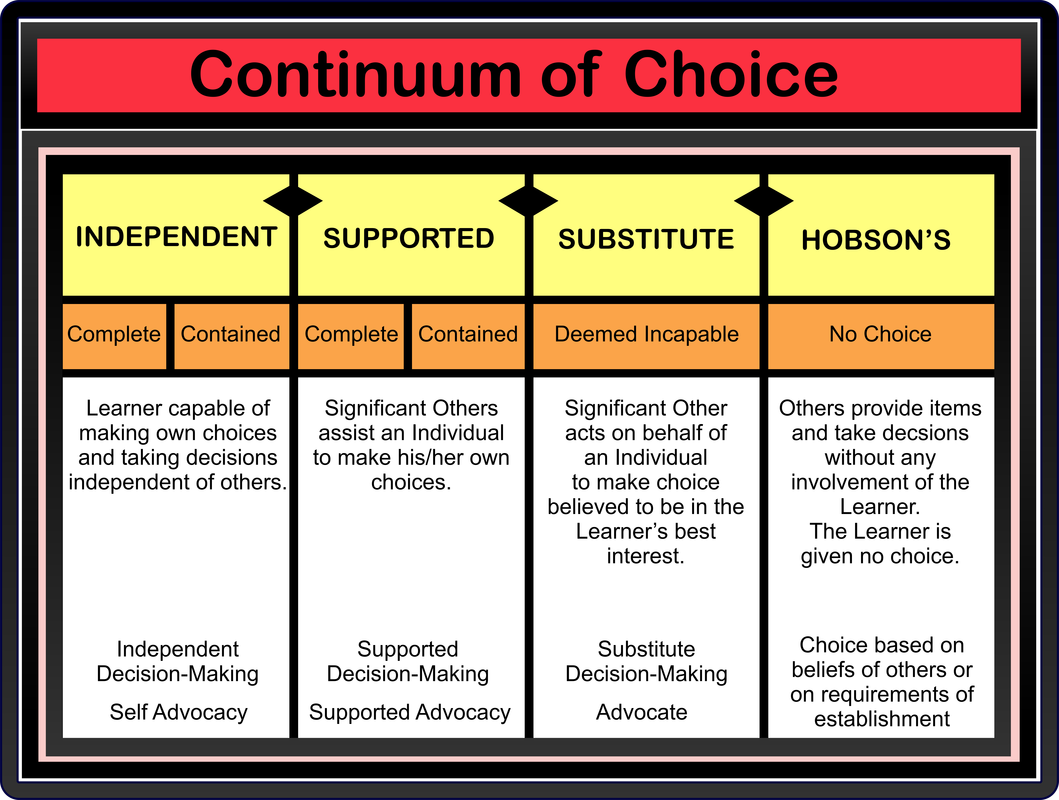

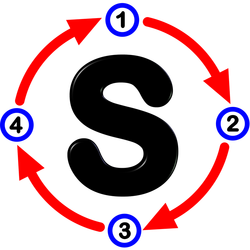

A Continuum of Choice

"The starting point is not a test of capacity, but the presumption that every human being is communicating all the time and that this communication will include preferences. Preferences can be built up into expressions of choice and these into formal decisions. From this perspective, where someone lands on a continuum of capacity is not half as important as the amount and type of support they get to build preferences into choices."

Beamer and Brookes (2001, page 4)

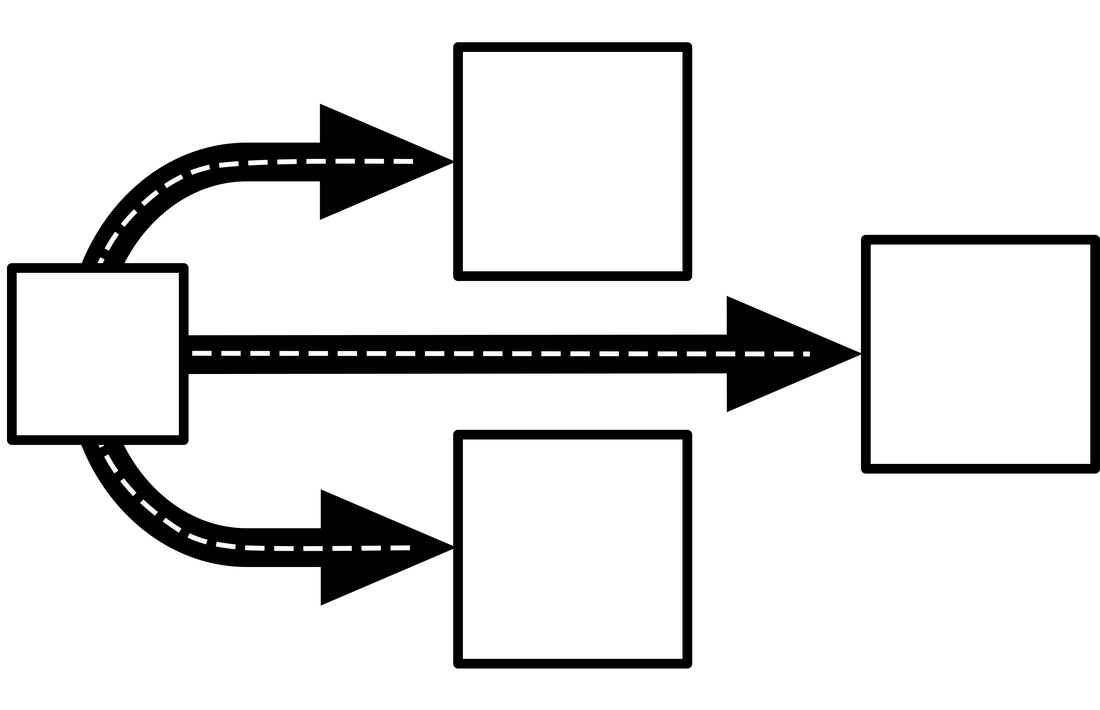

Making a decision involves having a choice. However, having a choice and decision-making cannot be viewed simply in one way; there is in fact a 'Continuum of Choice'.

The continuum may be split into four areas:

- Independent Choice (Contained and Complete);

- Supported Choice;

- Substitute Choice;

- Hobson's Choice (No Choice);

Independent decision-making involves the Learner deciding for himself without the assistance of any outside person. Even if the Learner were to ask another's opinion, any decision reached would still be considered as independent.

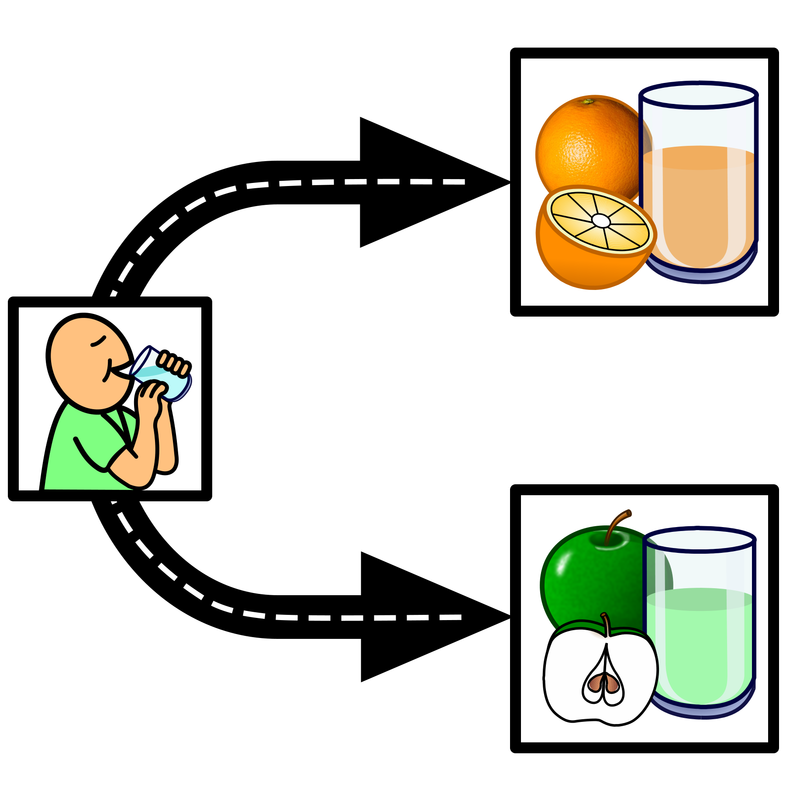

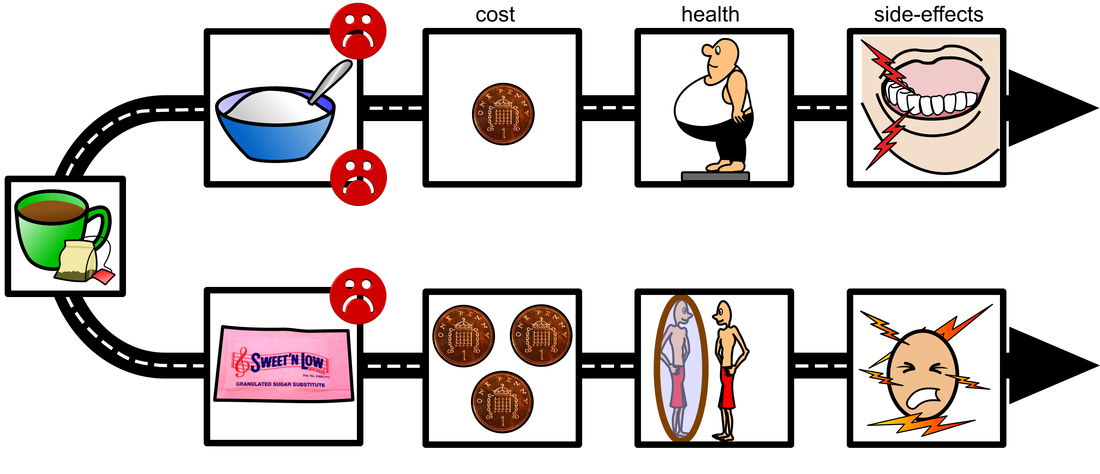

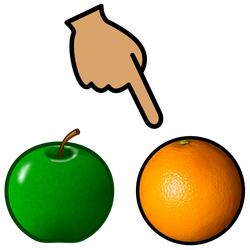

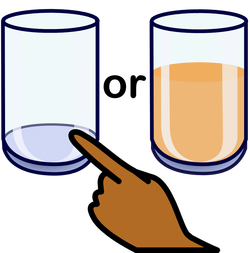

- Contained Choice is defined as a choice that is governed by some external limiting factor imposed by another. Examples of Contained Choice include the provision (by an another) of an array of items from which a Learner may select: for example, apple juice or orange juice at break time. The choice is 'contained', decided and thus constrained by another person.

- Complete Choice is defined as a complete freedom of choice. Although circumstances themselves may act to constrain the choice. While many would consider this notion chimeric, an important factor in reports on quality of life issues is the amount of control an individual is able to exert over daily events and his/her ability to makes choices.

One may argue that the notion of Complete Choice is an illusion and that all choice involves some aspect of constraint:

" Human beings are essentially social creatures. What they are and what they might be depends both on themselves and upon the societies in which they grow up and make their choices. Choices, however, are always made within some framework of constraint." (Twine 1994)

but, as choice becomes increasingly controlled by outside agencies so quality of life is reduced to the point where the individual becomes a puppet or a slave acting only on the permissions of another.

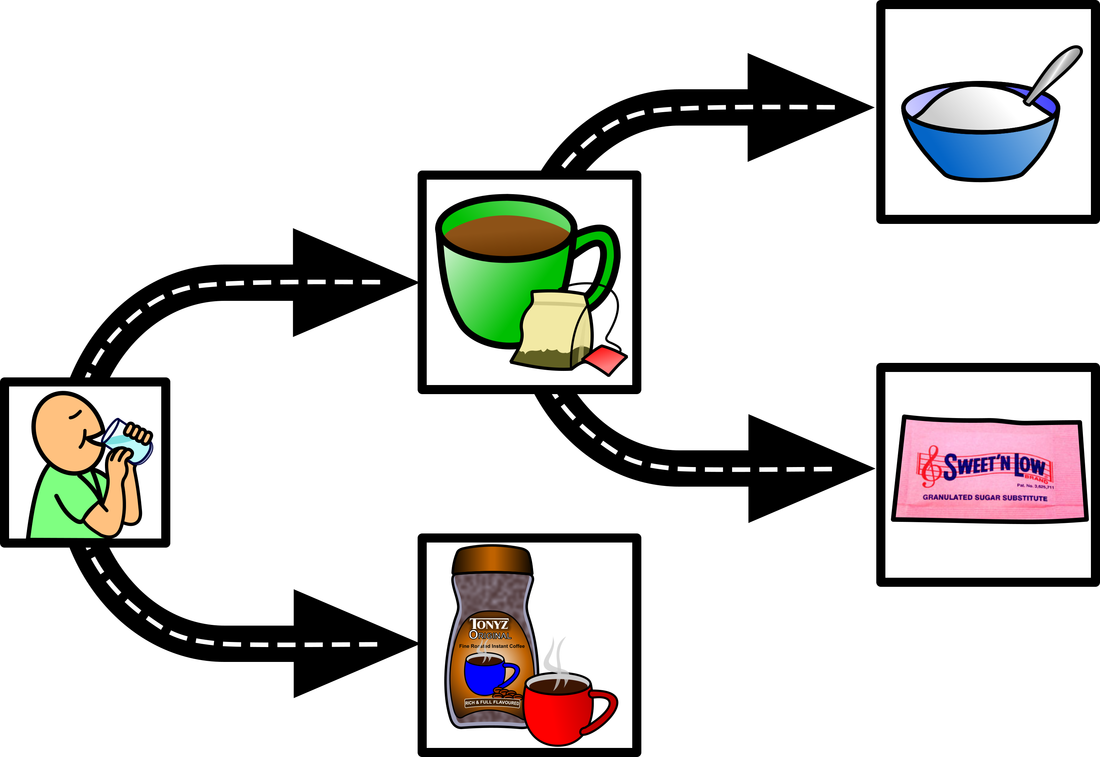

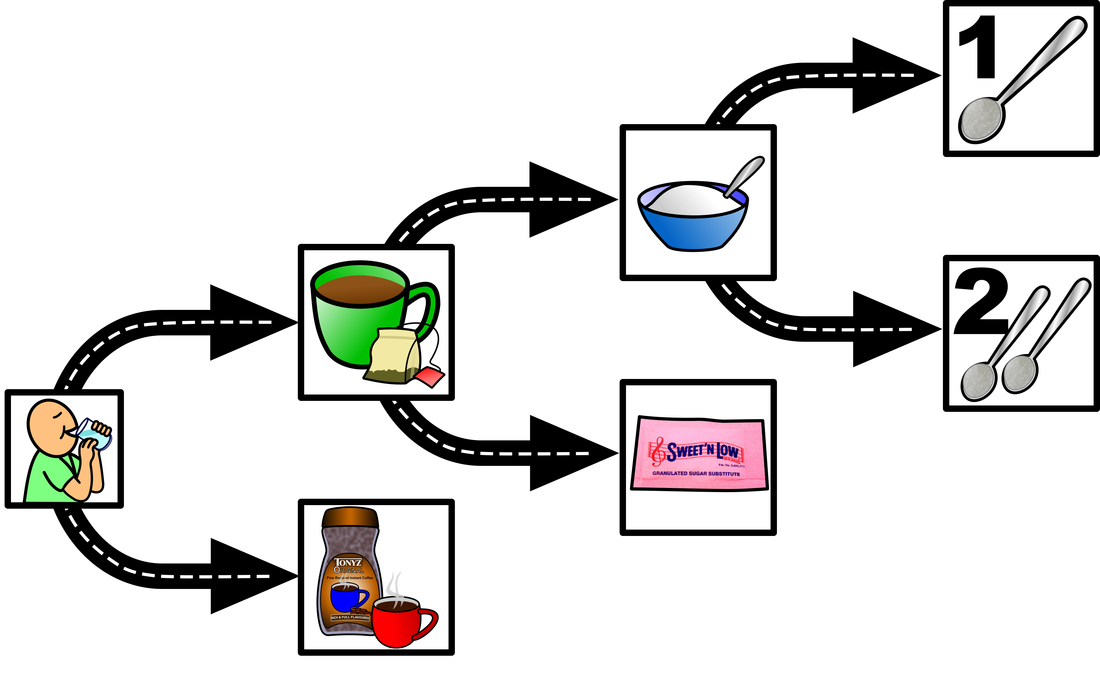

While both contained and complete choices may have consequences, typically, Significant Others support contained choices by removing those that may have detrimental long term effects. Although some individuals may be able to make an everyday contained choice independently (tea or coffee?), they might need significant assistance with complete choices that have far longer term consequences (Live at home or live in sheltered provision in the community?).

It should be noted that, at different times and in different situations, Learners may be independent in one area of choice and supported in another and 'experience' (in a sense the Learner does not experience as another makes the choice on his/her behalf) substituted choice at others.

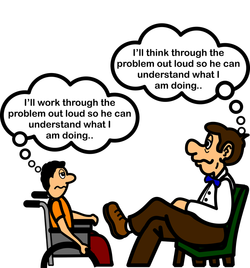

Supported decision-making is an approach for assisting Individuals Experiencing Learning Difficulties to make choices. The Learner is assisted to make important decisions either by a particular group of Significant Others or a Specific Other ( perhaps a parent or other relative, carer or teacher). The role of those supporting is NOT to make the decision on behalf of the Learner but to help him/her to:

- gather information;

- evaluate the options;

- consider the consequences of each choice.

Substitute decision-making involves an advocate acting on behalf of a Learner in his or her 'best interest'. If the Learner was believed to be incapable of understand the varying aspects of the choice or was so ill as to be temporarily incapacitated, a Significant Other (or Others) might be asked to make a decision on the person's behalf.

Hobson's Choice refers to the 1915 play by Harold Brighouse and four subsequent films of the same. However, it's origins date back to the mid to late 16th century to Thomas Hobson, a livery stable owner, who was reputed to have given his customers 'no choice': they could either take a specific horse from a specific place or leave with nothing at all. Hobson's choice is therefore no choice at all (Here's some tea) perhaps made on a belief that this is what the Learner wants (without any real evidence) but, more likely, at the whim of another or to meet the needs of the establishment itself (We got a bulk order of tea cheaply and so everyone will have tea!).

At different times of the day, and faced with different types of decisions, an individual Learner may encounter every type of choice on the continuum:

- at morning break, s/he may make an independent choice of a contained set of drinks;

- at a meeting in the morning, s/he may make a supported choice on some aspect of future curriculum choice;

- during a hospital visit a parent may decide on the best course of action regarding a particular medical issue;

- a trip out with the family in the evening may be to see a film decided by another member of the family with no reference to the Learner.

Click on the above image to download it.

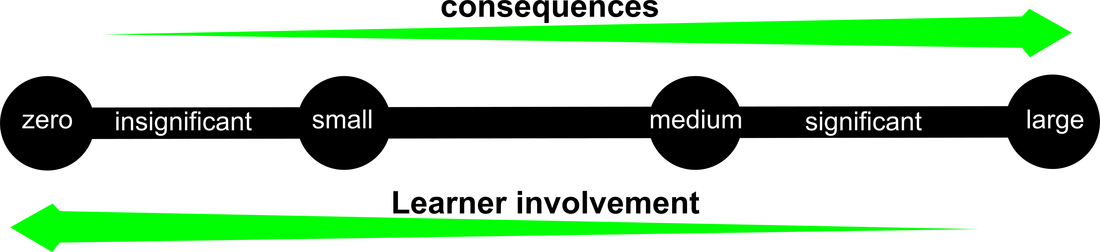

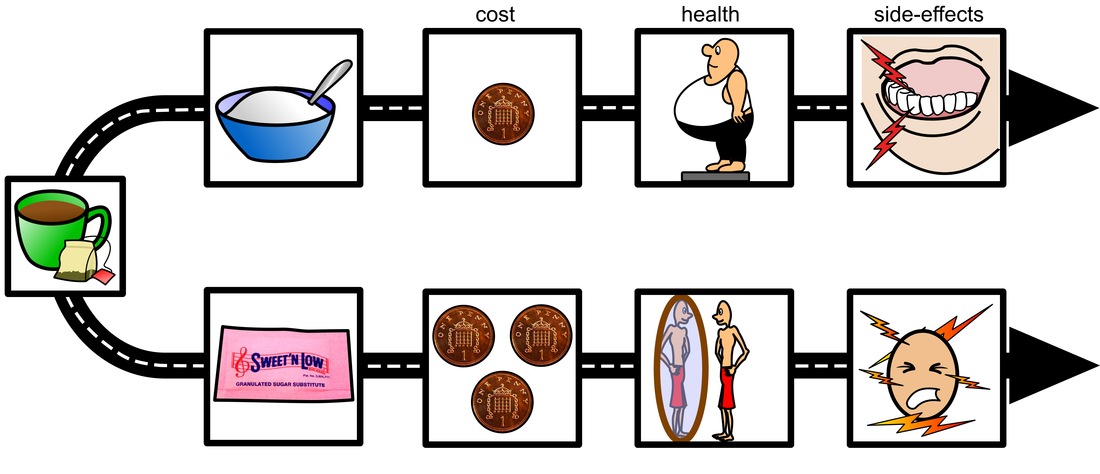

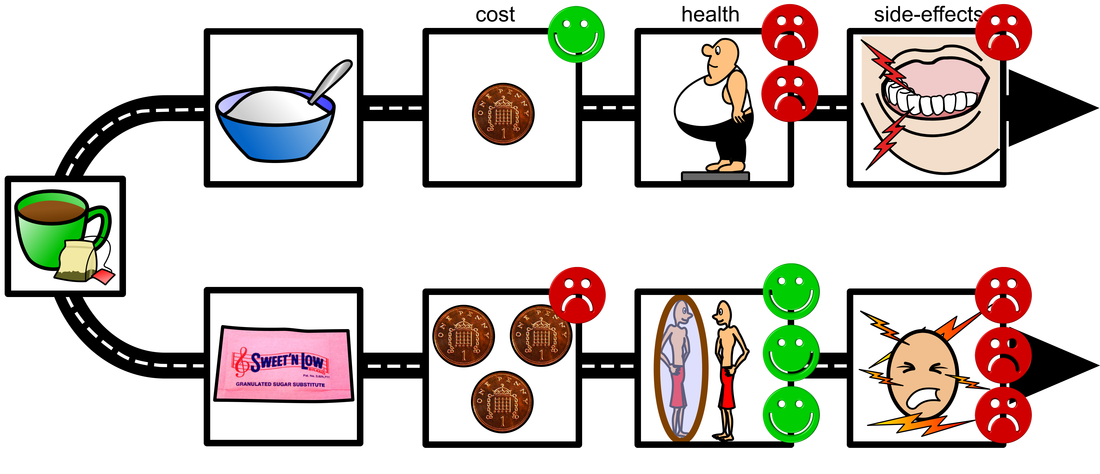

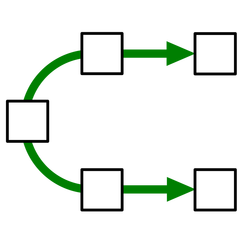

A Preference for Choice: A Continuum of Consequence

"An important distinction needs to be made between ‘expressing a preference’ and ‘making a choice’. Preferences are presented as expressing a subjective like/dislike of a particular thing which the individual already has some prior experience (for example, preferred foods, activities, people). In contrast, choice making is a process in which options or alternatives are identified, weighed up and a selection made (Kearney & McKnight, 1997; Ware, 2004; Smyth & Bell, 2006). Choice-making is therefore a cognitively more complex and demanding activity. At the same time, choices vary from simple to complex according to the demand made on an individual’s cognitive processing skills and abilities. For example, making choices about the future requires the ability to anticipate events and weigh-up potential consequences (Ware, 2004)."

Mitchell W. (2012) page 7

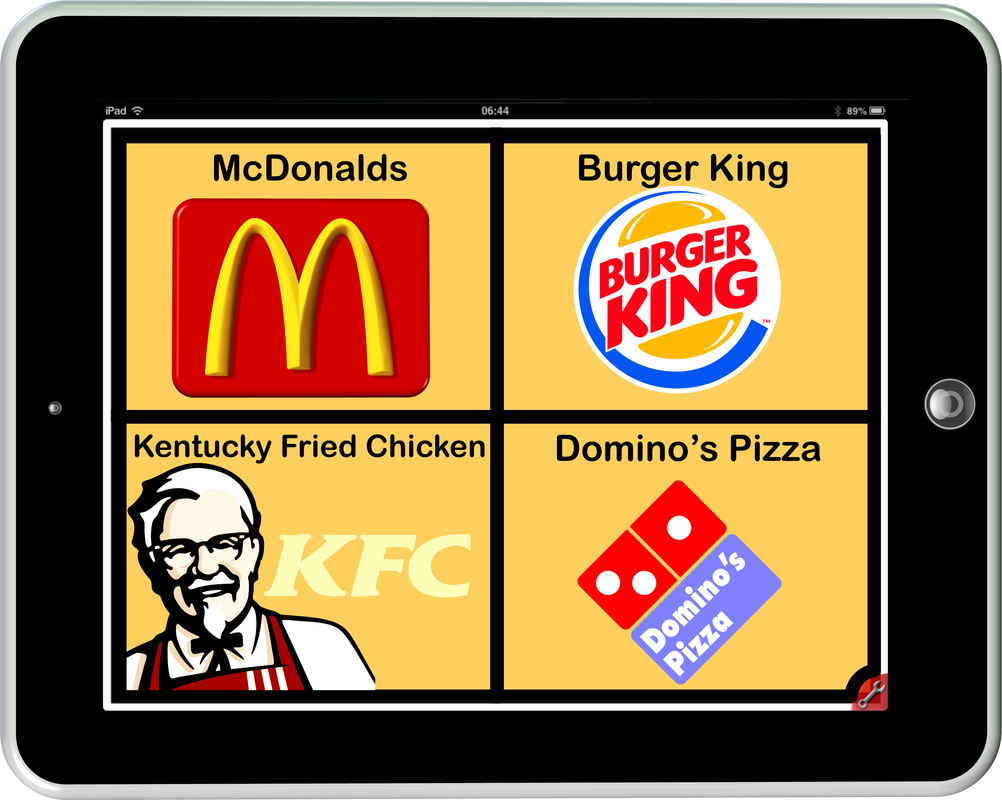

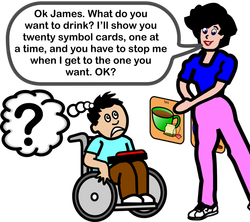

I am not sure that I agree that a preference is not a choice although it is but a matter of semantics. If an individual is stating a preference, s/he is indicating a choice (I prefer Heinz soup) even though another option is what has been actually provided (the Learner was given another brand of soup and communicated a preference for Heinz while consuming the soup provided). If a Learner was in a conversation with others and someone stated they loved Campbell's soup, the Learner might also indicate his/her preference for Heinz: while nothing is given and, thus, no soup is actually consumed here, there is still some form of choice in the Learner's consciousness - Heinz over Campbell's. However, Ms. Mitchell is pointing out that there is a continuum concerning the importance of specific choices with some having significantly more impact on the future quality of life of an individual than others ( a choice of future placement vs a choice of what to drink today for example). While agreeing on that issue, it would be wrong to somehow devalue the notion of 'choosing' what to drink as a mere 'preference' and therefore unimportant (I am certain that this is not what Mitchell is saying: she is simply pointing out some choices have longer term impact and consequences); Learners have to learn to choose and this should begin with arrays of items from the far left of this 'continuum of consequence' (see diagram below); that is, for example, with choosing a drink rather than choosing where to live. Indeed, for some Learners, quality of life may be determined, in part, by being able to express such simple choices. Furthermore, skills developed in making choices at this level will make it more likely that choice from other parts of the continuum are made with more comprehension. It is also likely if choice is routine at this 'lower' level, it is less likely to be overlooked when it comes to items from the far right of the continuum, However, Significant Others may adopt a varying stance on the involvement of the individual in choices as they move to the right portion of the continuum, assuming a Learner inability to comprehend the complexity, the consequence, or the risk:

"Complexity was also spoken about in terms of its ‘significance’, and this meant the potential consequences or impact of a decision on future well-being. The importance of their child being able to comprehend consequences and, more importantly, being able to understand possible future outcomes was noted by parents of young people with different levels of learning disabilities (both moderate and severe). When parents felt their child did not have the cognitive ability to comprehend the ‘significance’ of a choice, the level of the young people’s involvement in the choice-making process was reduced." Mitchell (2012) Page 17

While some choices are obviously more complex, more risky, and have longer term consequences, it should be possible to involve the Learner in the process by making the necessary information available to him/her at an appropriate level:

"Other parents recognised and valued their son/daughter developing choice-making skills. Parents described supporting the acquisition of these skills by, for example (as noted above), simplifying choices and, where possible, providing direct experience of choice options. Parents also acted as information providers, seeking out information and/or interpreting complex information into a more understandable format for their child. Information filtering was here used in a facilitative rather than protective manner." Mitchell (2012) Page 21

Mitchell W. (2012) page 7

I am not sure that I agree that a preference is not a choice although it is but a matter of semantics. If an individual is stating a preference, s/he is indicating a choice (I prefer Heinz soup) even though another option is what has been actually provided (the Learner was given another brand of soup and communicated a preference for Heinz while consuming the soup provided). If a Learner was in a conversation with others and someone stated they loved Campbell's soup, the Learner might also indicate his/her preference for Heinz: while nothing is given and, thus, no soup is actually consumed here, there is still some form of choice in the Learner's consciousness - Heinz over Campbell's. However, Ms. Mitchell is pointing out that there is a continuum concerning the importance of specific choices with some having significantly more impact on the future quality of life of an individual than others ( a choice of future placement vs a choice of what to drink today for example). While agreeing on that issue, it would be wrong to somehow devalue the notion of 'choosing' what to drink as a mere 'preference' and therefore unimportant (I am certain that this is not what Mitchell is saying: she is simply pointing out some choices have longer term impact and consequences); Learners have to learn to choose and this should begin with arrays of items from the far left of this 'continuum of consequence' (see diagram below); that is, for example, with choosing a drink rather than choosing where to live. Indeed, for some Learners, quality of life may be determined, in part, by being able to express such simple choices. Furthermore, skills developed in making choices at this level will make it more likely that choice from other parts of the continuum are made with more comprehension. It is also likely if choice is routine at this 'lower' level, it is less likely to be overlooked when it comes to items from the far right of the continuum, However, Significant Others may adopt a varying stance on the involvement of the individual in choices as they move to the right portion of the continuum, assuming a Learner inability to comprehend the complexity, the consequence, or the risk:

"Complexity was also spoken about in terms of its ‘significance’, and this meant the potential consequences or impact of a decision on future well-being. The importance of their child being able to comprehend consequences and, more importantly, being able to understand possible future outcomes was noted by parents of young people with different levels of learning disabilities (both moderate and severe). When parents felt their child did not have the cognitive ability to comprehend the ‘significance’ of a choice, the level of the young people’s involvement in the choice-making process was reduced." Mitchell (2012) Page 17

While some choices are obviously more complex, more risky, and have longer term consequences, it should be possible to involve the Learner in the process by making the necessary information available to him/her at an appropriate level:

"Other parents recognised and valued their son/daughter developing choice-making skills. Parents described supporting the acquisition of these skills by, for example (as noted above), simplifying choices and, where possible, providing direct experience of choice options. Parents also acted as information providers, seeking out information and/or interpreting complex information into a more understandable format for their child. Information filtering was here used in a facilitative rather than protective manner." Mitchell (2012) Page 21

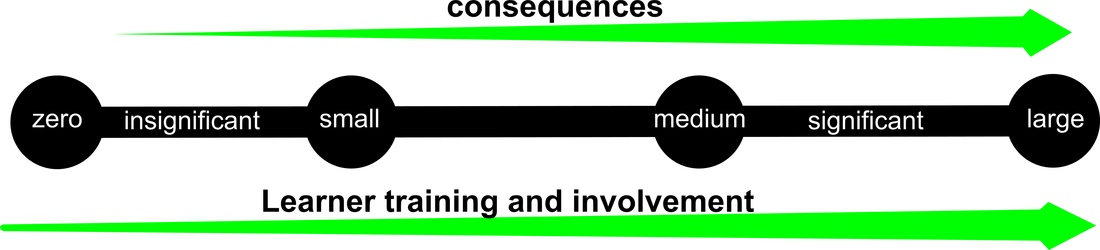

Typically the continuum of consequence is thus painted as depicted above with an inverse relationship between the significance (and risk) and any Learner involvement (as the significance of the consequences increases so Learner involvement in the choice decreases).

"Too often, families, teachers and other well-intentioned people protect youth with disabilities from making mistakes and avoid discussing the details and potential ramifications of the youth’s disability. Instead, they focus on the positive and steer the youth away from many experiences where there is a potential for failure."

(Bremer, Kachgal, & Schoeller 2003)

This is not an ideal state of affairs although it is understandable. However, as has already been shown, it need not be one of selecting different approaches to the involvement of an individual Learner in the choice making process at different points in the continuum but, rather, one of making information and experiences available at an appropriate level so as to:

"Respecting and understanding choice plays an important role in safeguarding adults. Listening to individuals’ preferences about issues such as where they wish to live and with whom, can help ensure that people with learning disabilities are able to live alongside others with whom they feel comfortable and safe. Thinking carefully and wisely about how individuals make choices and any limitations they may have with regard to choice making and consent, can enable their supporters to ensure that choices are respected, while still taking steps to protect individuals from risks or dangers which they have not appreciated or anticipated."

Department of Social Work, University of Hull 2009

Thus, a 'better practice' Continuum of Consequence might be more akin the diagram below where Learner training prepares for future need such that the individual may be empowered to take more control over his or her life choices.

"Too often, families, teachers and other well-intentioned people protect youth with disabilities from making mistakes and avoid discussing the details and potential ramifications of the youth’s disability. Instead, they focus on the positive and steer the youth away from many experiences where there is a potential for failure."

(Bremer, Kachgal, & Schoeller 2003)

This is not an ideal state of affairs although it is understandable. However, as has already been shown, it need not be one of selecting different approaches to the involvement of an individual Learner in the choice making process at different points in the continuum but, rather, one of making information and experiences available at an appropriate level so as to:

- be inclusive;

- teach and develop Learner choice making abilities.

"Respecting and understanding choice plays an important role in safeguarding adults. Listening to individuals’ preferences about issues such as where they wish to live and with whom, can help ensure that people with learning disabilities are able to live alongside others with whom they feel comfortable and safe. Thinking carefully and wisely about how individuals make choices and any limitations they may have with regard to choice making and consent, can enable their supporters to ensure that choices are respected, while still taking steps to protect individuals from risks or dangers which they have not appreciated or anticipated."

Department of Social Work, University of Hull 2009

Thus, a 'better practice' Continuum of Consequence might be more akin the diagram below where Learner training prepares for future need such that the individual may be empowered to take more control over his or her life choices.

It is important that Significant Others:

Example: 'Good . . . that's a good choice." (Jackson and Jackson 1999 page 78)

Always give time appropriate to the persons's abilities." (Jackson and Jackson 1999 page 78)

- praise the Learner for making a choice (even if they disagree with it);

- give positive feedback on good choice ("That's a great choice John because it will ... well done!")

Example: 'Good . . . that's a good choice." (Jackson and Jackson 1999 page 78)

- provide non-coercive consequential feedback on poor choices ("If that is what you want John OK. If you choose that though it will mean ... It's OK to choose something else if you want to but its also OK to keep that choice. What do you want to do?"). The point here is not to make the Learner change his/her mind and go with what you want but rather to help them think about the consequences of their actions. Sometimes it is only through making a bad choice that we learn what a good choice looks like and thus we should not try to prevent all choices we consider to be poor unless it is threatening to the Learner.

Always give time appropriate to the persons's abilities." (Jackson and Jackson 1999 page 78)

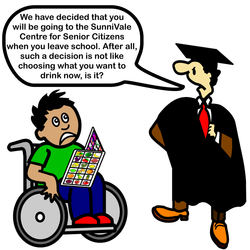

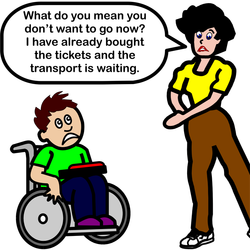

- allow Learners the option to change their minds. A change of mind is not unusual, it is something that we all do and therefore should be as acceptable, without criticism, in Learner s too. Of course, it is an undesirable state of affairs, if you have already purchased tickets and booked a journey as a result of a choice made and the Learner then changes his/her mind at the very last minute.

No Choice

While choice is generally a good thing for staff to be providing for those they facilitate there will inevitably be occasions when they have to say 'no'. This is likely to be experienced by the Significant Others involved with a sense of guilt and or frustration:

"Although most participants felt that choices were on the whole never impossible there were clearly times when they had to say ‘no’. Being unable to provide choices in these instances often left participants feeling both guilty and frustrated." (Bradley 2012)

Unless you are a person with unlimited resources there will be times in your life when you are unable to do something that you desire to do. This probably applies to 99.9 percent of the population. Some will go into debt and cause themselves additional problems in response to such a situation, some will attempt to put off the desire until some future time and work towards making it a reality, and some will understand that this particular desire is but a pipe-dream and get on with their day to day existence. Learning to live with the practicalities of timetables and resources is a necessary facet of everyone's existence: you cannot simply elect not to turn up for work or for school without some consequence and you cannot simply go out and spend a few million on a country estate if your income does not support such an expenditure. We all have to learn to live with 'no'. However, we have the benefit of understanding the reasons why 'no' is the outcome, how much more problematic would it be for an individual without the mental capacity to understand such closure of a desired path? As we have seen, it is also problematic for the majority of Significant Others who have to communicate that a particular desire is currently or permanently unavailable.

Why do we have to say no? There are a number of reasons why a Significant Other may have to say no to a person in their care:

Strategies

"Although most participants felt that choices were on the whole never impossible there were clearly times when they had to say ‘no’. Being unable to provide choices in these instances often left participants feeling both guilty and frustrated." (Bradley 2012)

Unless you are a person with unlimited resources there will be times in your life when you are unable to do something that you desire to do. This probably applies to 99.9 percent of the population. Some will go into debt and cause themselves additional problems in response to such a situation, some will attempt to put off the desire until some future time and work towards making it a reality, and some will understand that this particular desire is but a pipe-dream and get on with their day to day existence. Learning to live with the practicalities of timetables and resources is a necessary facet of everyone's existence: you cannot simply elect not to turn up for work or for school without some consequence and you cannot simply go out and spend a few million on a country estate if your income does not support such an expenditure. We all have to learn to live with 'no'. However, we have the benefit of understanding the reasons why 'no' is the outcome, how much more problematic would it be for an individual without the mental capacity to understand such closure of a desired path? As we have seen, it is also problematic for the majority of Significant Others who have to communicate that a particular desire is currently or permanently unavailable.

Why do we have to say no? There are a number of reasons why a Significant Other may have to say no to a person in their care:

- lack of resources (availability of necessary staffing, finance, equipment or venue);

- too great a risk;

- too much of a good thing is likely to be bad for the Learner;

- dictate from a superior;

- environmental or occupational dictate (for example: timetable states that Learner is required to go to physiotherapy at this time);

- against the law;

- against the rules of the establishment;

- infringes another's rights;

- harms another;

- not in the individual's best interest;

- other pressures.

Strategies

- Avoidance: Do not provide options within choice arrays when they cannot be immediately provided (because staff are not available for example) if selected;

- Bypass: offer up a choice that brings the Learner back on track. For example, if the Learner is due in Physiotherapy and wants to go out to the park (and this cannot be provided) you might offer a choice of routes to get to Physio: Do you want me to come with you and we'll go by the tuck-shop or do you want Doreen to go with you? Bypass can also mean the provision of hopefully attractive alternative options that can be provided at that moment; "We can't do that just now but we can do this or this, which would you like to do?"