Fundamentals of AAC

Fifteen Fundamentals of AAC

“Nothing is so simple that it cannot be misunderstood.” Freeman Teague Jr.

This page covers fundamental issues in AAC and Special Education of which Talksense believes that you should be aware, You might believe that there are other fundamentals or that some of these are not fundamental at all; if so, why not contact us and tell us what you think - if we agree then your suggestion(s) will be added to this page for the benefit of all.

Please note that:

- some of the cartoon images on this webpage will expand to a larger size if you click them. If you wish to use any of them in another presentation, please contact Talksense for permission.

- while this page is basically complete, it may be updated from time to time.

- The Videos may be found on YouTube unless otherwise stated.

References and a Bibliography are provided at the end of each section, as appropriate, in the 'See Also' section. The bibliographies do not claim to be comprehensive. If you know of additional material which would be of benefit to other readers of this webpage why not contact Talksense and let us know using the form provided at the bottom of the page.

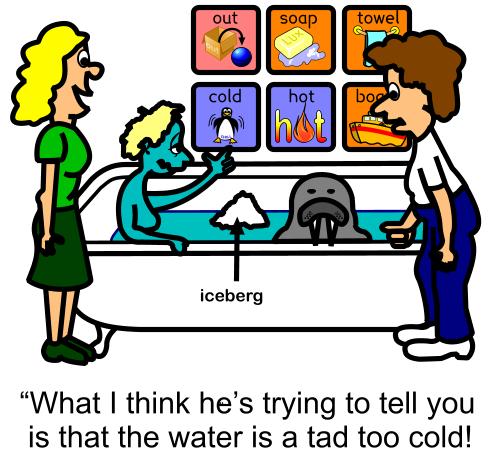

One: Communication Problems May Create Communication Problems

“Two monologues do not make a dialogue.” Jeff Daly

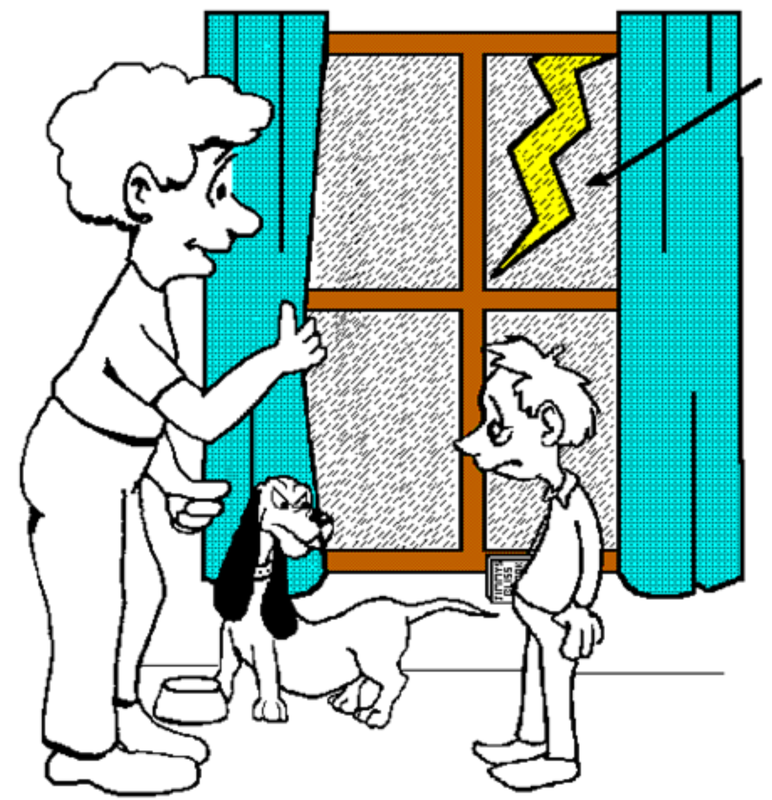

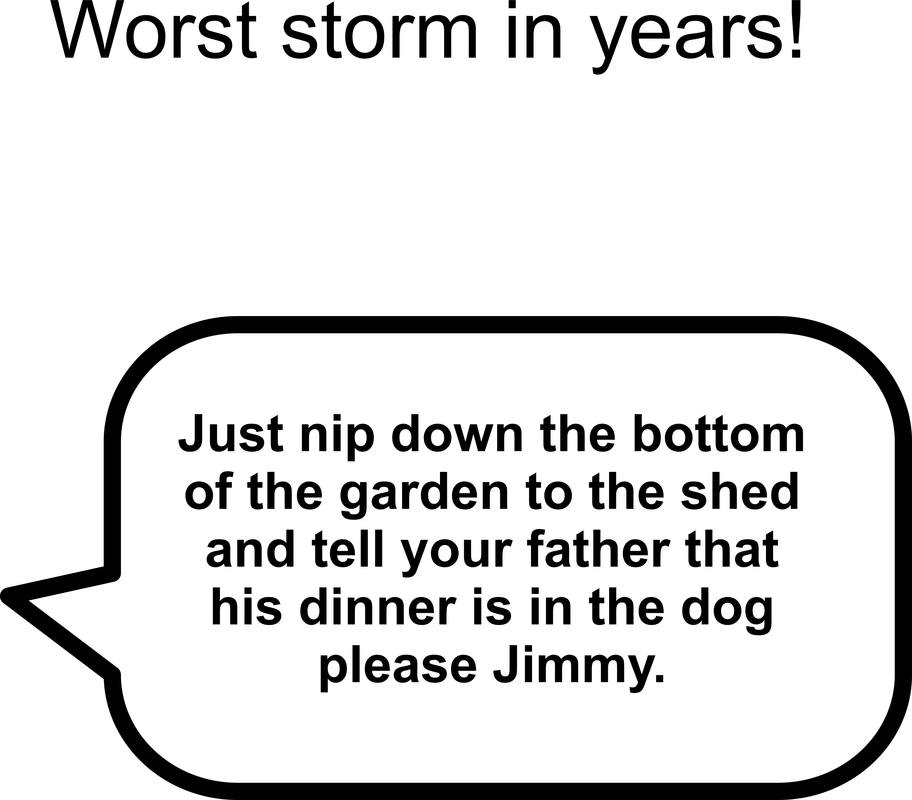

The problem with a communication problem is that it can be self fulfilling. That is, the very nature of the problem can cause others (we will refer to the 'others' as 'Communication Partners') to alter their standard communicative behaviour. This alteration of behaviour by the Learner's Communication Partners can itself reinforce the problem. For example, communication may be so slow that it is seen as painful by some potential partners and they seek to avoid the situation altogether. With a lack of Communication Partners, the Learner has no-one with whom to practice skills in the real world and, as such, a failure to make significant progress is possible. The Learner may thus reject the augmentative communication methodology altogether believing it to be of no use.

Typically, communication rates in everyday conversation vary between 140 to 180 words per minute (wpm)(Wingfield, A. & Grossman, M. 2006. Language and the Aging Brain: Patterns of Neural Compensation Revealed by Functional Brain Imaging, Journal Of Neuro-Physiology, Volume 96(6), pp. 2830 - 2839 ) (see also Dlugan). However, when one partner's rate falls to less than 50% of the lower level then the other partner's communicative behaviour may alter significantly. As Learners of AAC normally operate at much lower levels than this (See for example: University of Washington, Rate Enhancement. Augmentative and Alternative Communication at the University of Washington, Seattle.) there can be problems in the communicative behaviour of both others and Significant Others.

The short video excerpt below, from the American Comedians Bob Elliot and Ray Goulding entitled 'The Slow Talkers of America' , is a great example of the things that might happen if one communication partner's rate falls much below that which is the expected norm. While you are watching it, try to list all the ways that you believe a communication partner's behaviour may be altered by another's slow rate of speech.

The problem with a communication problem is that it can be self fulfilling. That is, the very nature of the problem can cause others (we will refer to the 'others' as 'Communication Partners') to alter their standard communicative behaviour. This alteration of behaviour by the Learner's Communication Partners can itself reinforce the problem. For example, communication may be so slow that it is seen as painful by some potential partners and they seek to avoid the situation altogether. With a lack of Communication Partners, the Learner has no-one with whom to practice skills in the real world and, as such, a failure to make significant progress is possible. The Learner may thus reject the augmentative communication methodology altogether believing it to be of no use.

Typically, communication rates in everyday conversation vary between 140 to 180 words per minute (wpm)(Wingfield, A. & Grossman, M. 2006. Language and the Aging Brain: Patterns of Neural Compensation Revealed by Functional Brain Imaging, Journal Of Neuro-Physiology, Volume 96(6), pp. 2830 - 2839 ) (see also Dlugan). However, when one partner's rate falls to less than 50% of the lower level then the other partner's communicative behaviour may alter significantly. As Learners of AAC normally operate at much lower levels than this (See for example: University of Washington, Rate Enhancement. Augmentative and Alternative Communication at the University of Washington, Seattle.) there can be problems in the communicative behaviour of both others and Significant Others.

The short video excerpt below, from the American Comedians Bob Elliot and Ray Goulding entitled 'The Slow Talkers of America' , is a great example of the things that might happen if one communication partner's rate falls much below that which is the expected norm. While you are watching it, try to list all the ways that you believe a communication partner's behaviour may be altered by another's slow rate of speech.

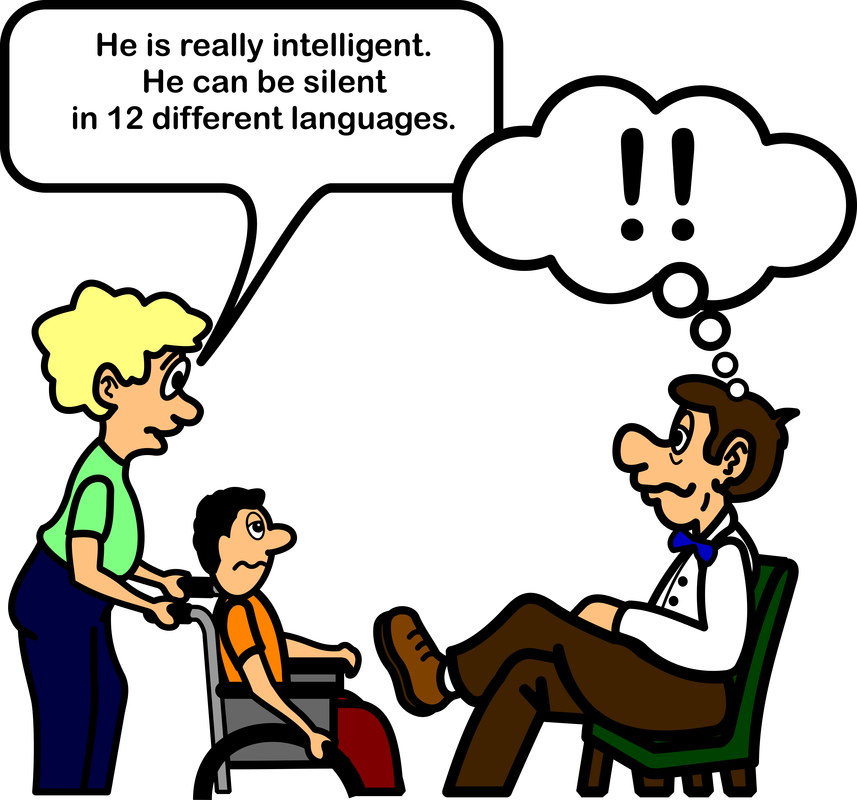

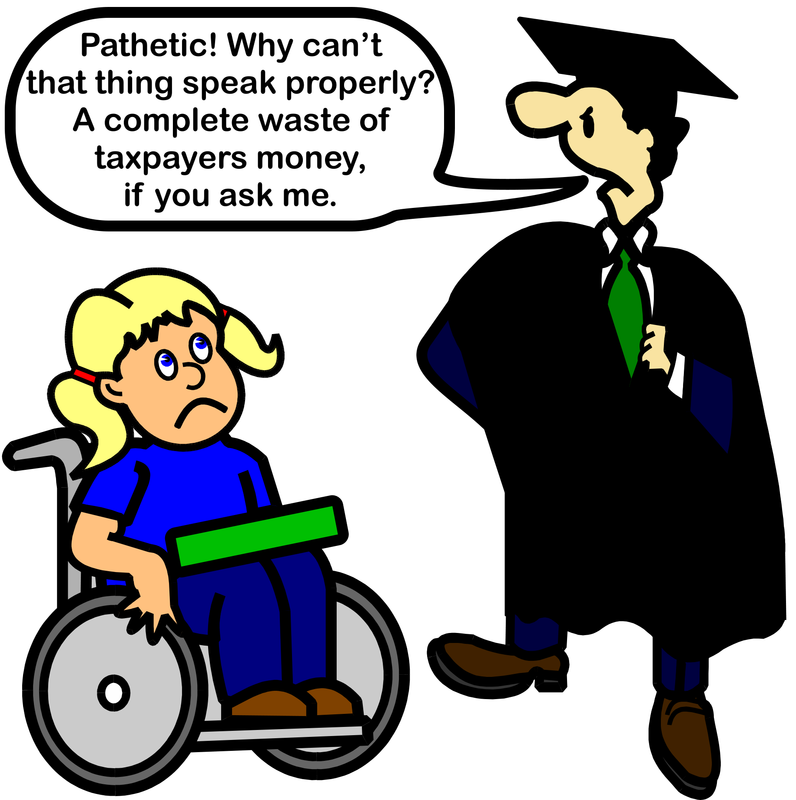

Slow speech is typically viewed as a lack of command of a language or of intellect:

"And Moses said unto the LORD, O my Lord, I am not eloquent, neither heretofore, nor since thou hast spoken unto thy servant: but I am slow of speech, and of a slow tongue." (King James Bible, Exodus 4:10)

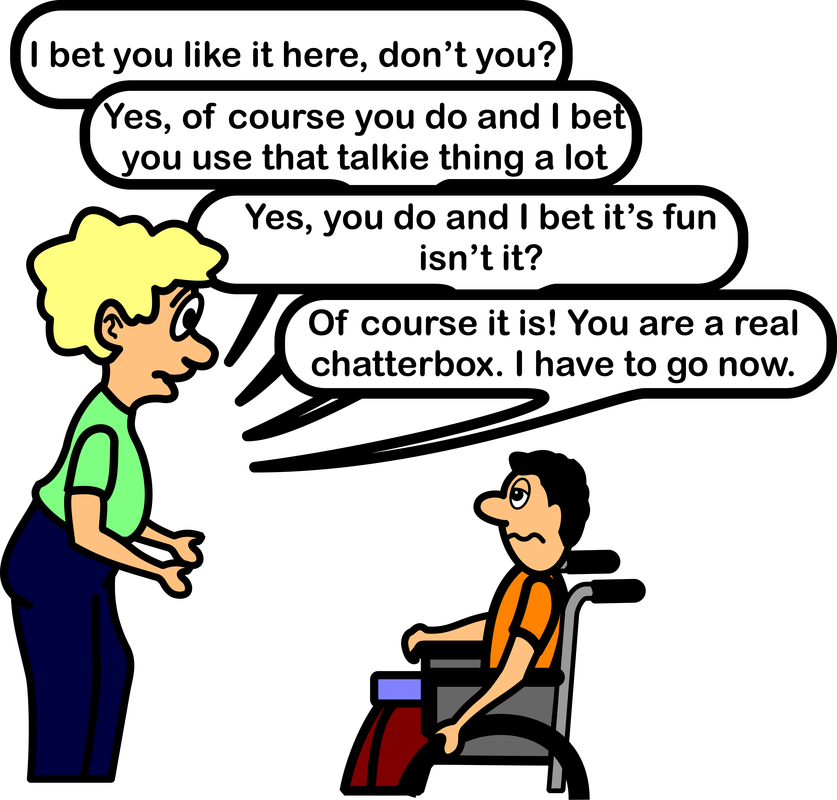

As communication rates tend towards zero so communication partner behaviours deviate from the norm. We can see this depicted in an amusing way in the video clip above: As communication rates tend towards zero, the potential Communication Partner may:

This list does not claim to be exhaustive; you may have thought of or experienced other behaviours that are seemingly consequential of slow rates of Learner communication. While some of these behaviours may be expected of the 'uninitiated other' (person in the street), they should not be present in educational establishments that seek to support and progress Learners requiring the use of an AAC system.

"And Moses said unto the LORD, O my Lord, I am not eloquent, neither heretofore, nor since thou hast spoken unto thy servant: but I am slow of speech, and of a slow tongue." (King James Bible, Exodus 4:10)

As communication rates tend towards zero so communication partner behaviours deviate from the norm. We can see this depicted in an amusing way in the video clip above: As communication rates tend towards zero, the potential Communication Partner may:

- adjust his/her behaviour to compensate for the slower rates of interchange;

- begin to fidget and show signs of impatience;

- make predictions of words or remaining sections of sentences in order to speed the communicative flow;

- make an excuse to cut short the conversation;

- cut short the conversation (no excuse);

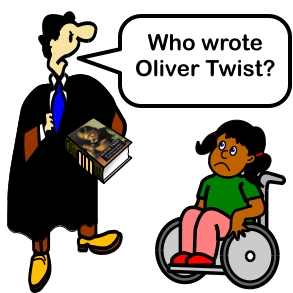

- take greater control of the communication by speaking more and allowing the Learner to speak less;

- ask and then answer his/her own questions;

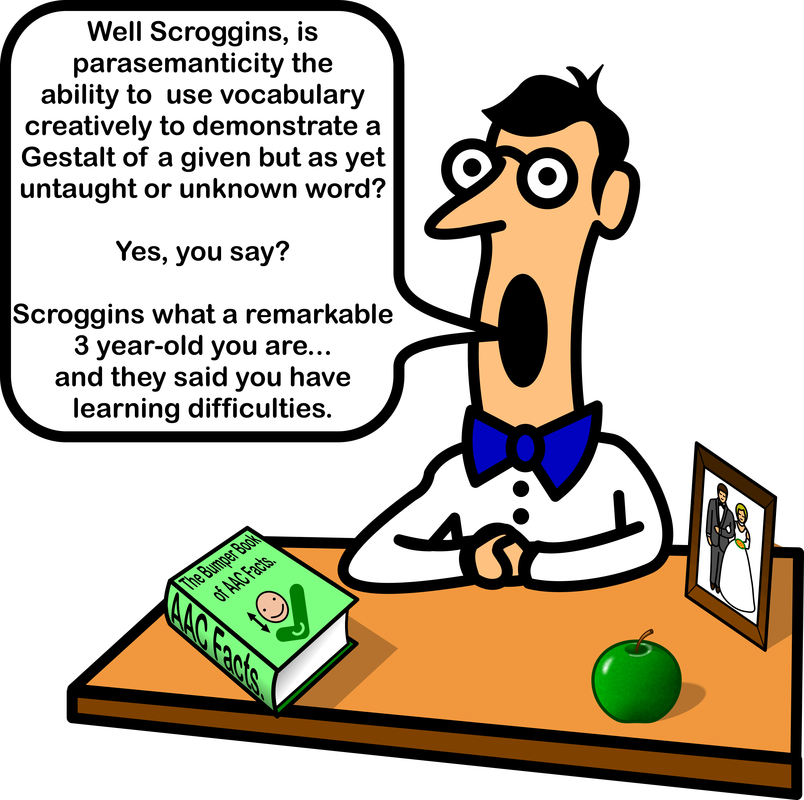

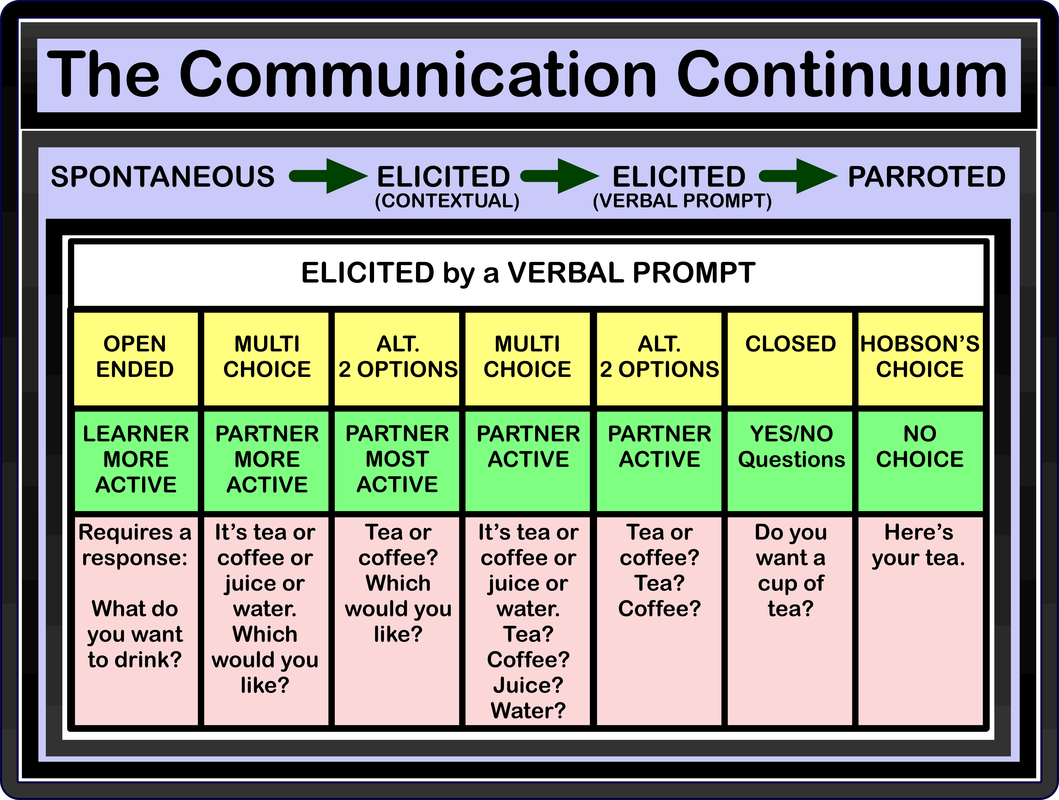

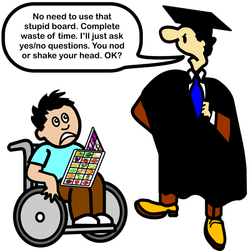

- move to a closed (yes/no) question format with the Learner;

- adopt a compensatory communicative strategy (for example, asking the Learner to build a sentence while s/he does something else);

- avoid initiating any further conversation so as to keep the interchange as short as possible;

- limit the conversation to social greetings only;

- begin to play with the learner's communication system without permission;

- adopt a non-communication-friendly position (for example towering over the Learner or moving to rear of the Learner to 'watch what they are doing')

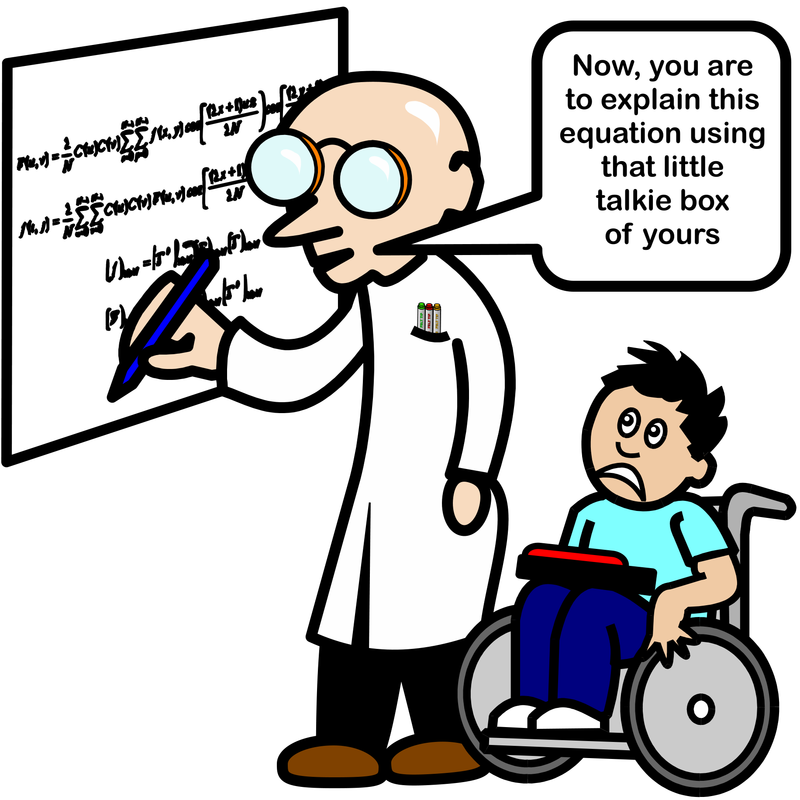

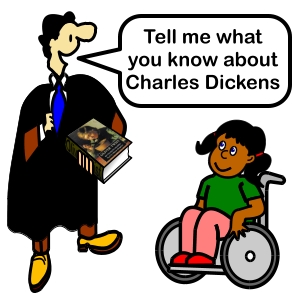

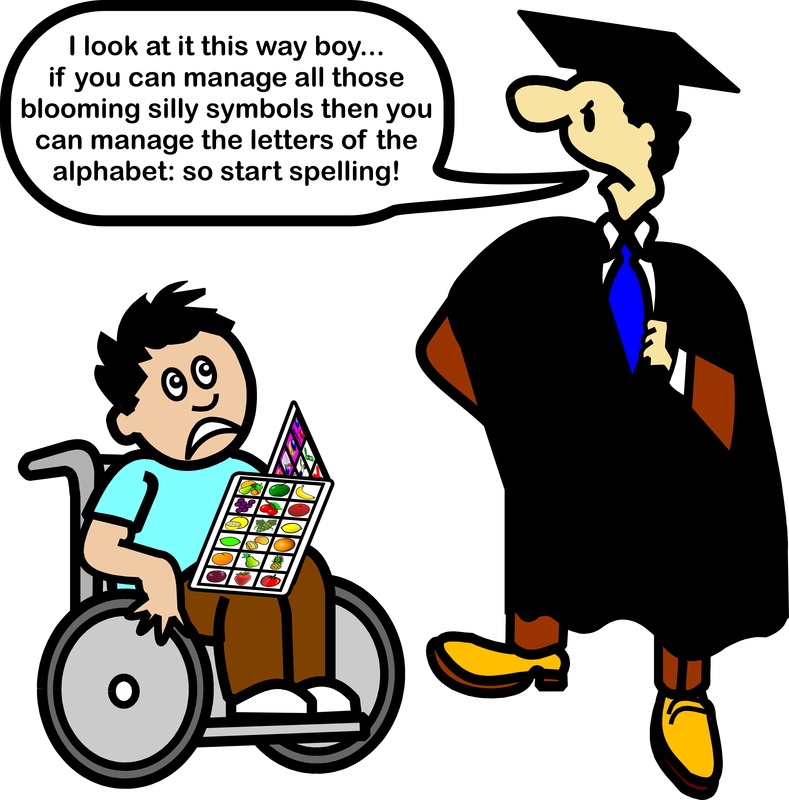

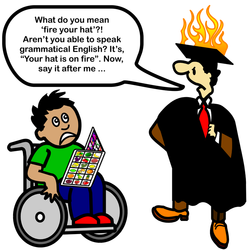

- move into 'didactic mode' - start to teach the learner how to say x and y (if they know);

- begin to talk to the Learner as though s/he was at an earlier stage of development;

- begin to patronize the Learner;

- belittle the Learner's communication system (especially if older partner to younger Learner);

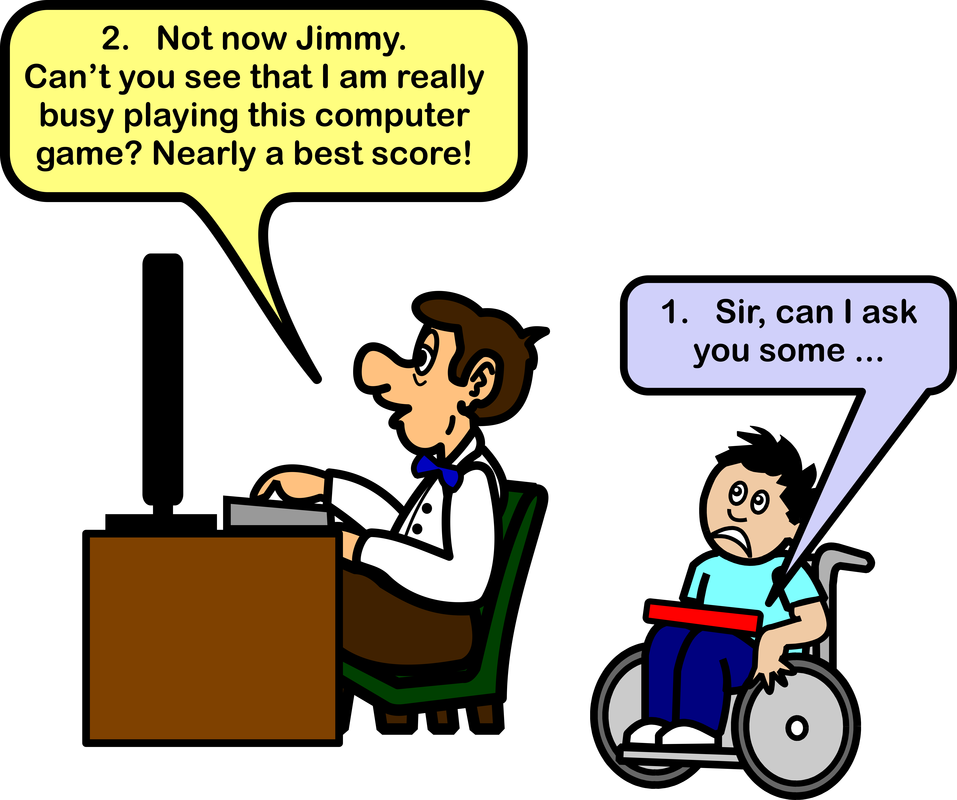

- ignore the Learner;

- ask another to deal with the communication interchange on their behalf;

- terminate the conversation abruptly;

- seek to avoid any communication interchange altogether.

This list does not claim to be exhaustive; you may have thought of or experienced other behaviours that are seemingly consequential of slow rates of Learner communication. While some of these behaviours may be expected of the 'uninitiated other' (person in the street), they should not be present in educational establishments that seek to support and progress Learners requiring the use of an AAC system.

|

While Communication Rate is one problem of the use of AAC, another issue is intelligibility. There are, at least two facets to this area. The first is the voice quality itself. When I first entered this field the Text To Speech systems (TTS) available sounded like a dalek with a sore throat on a bad day! For example, a student I taught was asked to welcome the then Head of the Manpower Services Team in the UK, a certain Mr Carter, during a visit to the college in which I was working. While the student performed brilliantly all that was almost intelligible was the person's name which pronounced as 'Mr. Farter' with much hilarity among the audience!! Needless to say, the intelligibility of TTS systems has progressed a very long way in the past thirty years and undoubtedly will continue to make even greater strides in the future until a TTS voice is indistinguishable from a natural voice. While the original Star Trek computer could speak but they could not know how much voice reproduction by computers would progress and the Star Trek voice sounds quite quaint these days!

There are many commercial TTS systems on the market; some can cost quite a lot of money. Generally speaking, the more you pay the better quality you get with better control over the voice parameters. It would be foolhardy to single any one out as worthy of attention because, like all other technology, it is moving at such a pace that any recommendation would probably be out of date by the time you are reading this! A search on the internet usually |

|

reveals several companies offering TTS systems and, typically, most allow the customer to select a voice form a range (nationality, sex, etc), type in a phrase, and listen to the resultant sound quality.

However, A Learner's communication system will normally have it's own TTS system and may not be able to work with any other (A quick call to your supplier should reveal if the system is capable to operating with another TTS system).

Most TTS systems are confused by some words especially proper nouns such as people's names (Aoife, Siobhan) and place names (Glodwick, Greenwich, Southall, etc) and thus have a mechanism by which you are allowed to override the system and tell it how to pronounce a particular form while retaining the correct spelling.

Microsoft have their own TTS system supplied freely with Windows. It is a little strange because the latest version (Windows Seven as I write this) only comes with one voice (Anna) whereas earlier versions had a choice of several voices. However, the latest voice is of a better quality than those previously available.

TTS makes any word accessible no matter how esoteric or infrequently required for example, the longest word in the OED (at 45 letters):

‘Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis’

I have never (until now!) had the need to use or to say this word, let alone program it into a Speech Generating Device (SGD). However, TTS would allow me to say it if I did.

While a recorded voice is always someone else’s voice, which the Learner may not want, especially as it is probably the voice of a sibling or a Significant Other (parent, teacher, therapist)(and, therefore may not even be sex or age appropriate), a TTS voice can (usually) be personalized to suit an individual providing a person’s ‘own’ voice. Such a voice does not rely (in the same way as does a recorded voice) on another person always being there to record new messages and, if the Learner is literate, s/he can input their own words!

Here are a list of websites for the different TTS systems of which I am aware in alpha order:

Acapela http://www.acapela-group.com/text-to-speech-interactive-demo.html

AT&T http://www2.research.att.com/~ttsweb/tts/demo.php

Babel See Acapela

Cepstral http://cepstral.com/demos/

Cereproc http://www.cereproc.com/

DecTalk http://www.fonixspeech.com/dectalk_legacy.php

Dhvani http://dhvani.sourceforge.net/

Elan See Acapela

Espeak http://espeak.sourceforge.net/

Festival http://www.cstr.ed.ac.uk/projects/festival/onlinedemo.html

Flite http://www.speech.cs.cmu.edu/flite/

iSpeech http://www.ispeech.org/text.to.speech.demo.php

Ivona http://www.ivona.com/

Infovox See Acapela

Loquendo http://www.loquendo.com/en/demo-center/tts-demo/

Lumenvox http://www.lumenvox.com/products/tts/

Model Talker https://www.modeltalker.org/

Nemours See Model Talker

NeoSpeech http://www.neospeech.com/?gclid=CLCpwYOTvqkCFQXybwodTERLfA

OpenSource http://sourceforge.net/search/?q=tts

Orpheus http://www.meridian-one.co.uk/orpheus.html

Realspeak http://www.nuance.co.uk/realspeak/

Svox http://www.svox.com/?page_id=138

Truvoice http://www.v3mail.com/download/ttsengines.htm

Vivotext http://www.vivotext.com/

The above list may not be comprehensive and some links may no longer be current. Talksense apologizes if this is the case.

While Talksense does not currently endorse one speech engine above any other, we found the video below on YouTube which is quite interesting. Remember, it is dated 2009 and technology moves very fast these days so it is well out of date!:

However, A Learner's communication system will normally have it's own TTS system and may not be able to work with any other (A quick call to your supplier should reveal if the system is capable to operating with another TTS system).

Most TTS systems are confused by some words especially proper nouns such as people's names (Aoife, Siobhan) and place names (Glodwick, Greenwich, Southall, etc) and thus have a mechanism by which you are allowed to override the system and tell it how to pronounce a particular form while retaining the correct spelling.

Microsoft have their own TTS system supplied freely with Windows. It is a little strange because the latest version (Windows Seven as I write this) only comes with one voice (Anna) whereas earlier versions had a choice of several voices. However, the latest voice is of a better quality than those previously available.

TTS makes any word accessible no matter how esoteric or infrequently required for example, the longest word in the OED (at 45 letters):

‘Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis’

I have never (until now!) had the need to use or to say this word, let alone program it into a Speech Generating Device (SGD). However, TTS would allow me to say it if I did.

While a recorded voice is always someone else’s voice, which the Learner may not want, especially as it is probably the voice of a sibling or a Significant Other (parent, teacher, therapist)(and, therefore may not even be sex or age appropriate), a TTS voice can (usually) be personalized to suit an individual providing a person’s ‘own’ voice. Such a voice does not rely (in the same way as does a recorded voice) on another person always being there to record new messages and, if the Learner is literate, s/he can input their own words!

Here are a list of websites for the different TTS systems of which I am aware in alpha order:

Acapela http://www.acapela-group.com/text-to-speech-interactive-demo.html

AT&T http://www2.research.att.com/~ttsweb/tts/demo.php

Babel See Acapela

Cepstral http://cepstral.com/demos/

Cereproc http://www.cereproc.com/

DecTalk http://www.fonixspeech.com/dectalk_legacy.php

Dhvani http://dhvani.sourceforge.net/

Elan See Acapela

Espeak http://espeak.sourceforge.net/

Festival http://www.cstr.ed.ac.uk/projects/festival/onlinedemo.html

Flite http://www.speech.cs.cmu.edu/flite/

iSpeech http://www.ispeech.org/text.to.speech.demo.php

Ivona http://www.ivona.com/

Infovox See Acapela

Loquendo http://www.loquendo.com/en/demo-center/tts-demo/

Lumenvox http://www.lumenvox.com/products/tts/

Model Talker https://www.modeltalker.org/

Nemours See Model Talker

NeoSpeech http://www.neospeech.com/?gclid=CLCpwYOTvqkCFQXybwodTERLfA

OpenSource http://sourceforge.net/search/?q=tts

Orpheus http://www.meridian-one.co.uk/orpheus.html

Realspeak http://www.nuance.co.uk/realspeak/

Svox http://www.svox.com/?page_id=138

Truvoice http://www.v3mail.com/download/ttsengines.htm

Vivotext http://www.vivotext.com/

The above list may not be comprehensive and some links may no longer be current. Talksense apologizes if this is the case.

While Talksense does not currently endorse one speech engine above any other, we found the video below on YouTube which is quite interesting. Remember, it is dated 2009 and technology moves very fast these days so it is well out of date!:

While the voice quality continues to improve, intelligibility is now governed more by what is said rather than how it is said. If a Learner has poor syntactic skills and builds sentences with deviant word ordering, it may be more difficult for others to process. While requests for clarification are common among Significant Others who know the Learner well, others might be embarrassed by asking and simply nod in agreement when in fact they have not understood what was spoken.

Our reaction to not understanding must not infringe one of the other fundamentals - that of positive staff attitudes. For a response that evidences less than good practice is likely to demoralize a Learner and may lead to a rejection of the AAC system itself. If you do not understand what a Learner is trying to say then there is no harm in simply saying so in a pleasant manner. Such statements should be accompanied by a request for clarification:

"I'm sorry Susie, my brain is not working well today. I do not understand what you are trying to tell me. Could you try to tell

me again using different words?"

It may be that this strategy fails too. Again, try and alleviate the situation and provide a simpler path for the the Learner to follow:

"I must be stupid today Susie. I still do not understand what you mean. I know what we can try. Can you try and tell me using

just one word what it is about? And we will figure it out together."

It is important that all conversations do not turn into 'teaching opportunities' (see item 10 below) as teaching is best left for specific areas and specific times. While it would appear there is no harm in helping the Learner to produce an intended message that you have just worked out with them, it so often becomes much more than that and can have the effect of alienating the Learner from the system. I have too often witness staff telling a Learner what they 'should have been saying' and then actually rejecting the request! Be careful, sometimes what staff think is helpful is actually quite the reverse!

If you do understand what has been said, even though it may have been said in a rather strange way, do NOT enter 'teacher mode'! Simply respond to the statement as though it had been in perfect English. You have understood and that is fantastic. Celebrate the Learner's achievement is creating a statement from words which was comprehensible, even if not perfect English syntax. Do no tell the Learner the 'correct way to say it' and then make them go through it all again until they have spoken it aloud without a mistake. Worse still, do not do that and then reject the request as well! If you simply must enter 'teacher mode', add the correct form of the the Learner statement to your response without any hint of sarcasm, criticism or belittlement:

LEARNER - Greenhouse now go want

LISTENER - Hi Sally. Oh you want to go to the greenhouse now? That's fine. I guess you need a key.

Would you like me to help you get it?

It is in such interactions that communicative skills are practiced, honed and reinforced. Sadly, sometimes, such interactions only serve to alienate the Learner from the AAC system. Don't let that happen to your Learners.

Communication is important, too important to be made problematic by the actions of others:

"Speech is power in our society. Hence, it should surprise no one that freedom of speech is the first right guaranteed to all Americans in the Bill of Rights. Deprived of speech or another means of effective communication, individuals become invisible. They are simply not heard. They are silenced. And, when people are silenced, others quickly lose sight of their right to be a part of humanity!" (Bryen, D. 1993)

"In the English speaking culture ......, a high value is placed on talking. Indeed, the more one talks, the more one is viewed as a desirable and an active conversational partner. In contrast, individuals who talk very little are often viewed as withdrawn and less competent, making their partners feel uncomfortable." (Hoag, L., Bedrosian, J., Johnson, D., Molineux, B. 1994)

"The goal of any communication system is to increase an individual’s ability to communicate more effectively and efficiently. Typically those who rely on augmentative communication systems communicate at slower rates and with restrictive vocabulary sets. The response by their speaking communication partners is to dominate the conversation by initiating, setting the topic, asking yes/no questions, not pausing long enough to allow the augmentative communicator to respond and closing the conversation. The augmentative communicator then may assume a very passive role in the conversation with reduced social experiences and reduced motivation to use the communication system." (Morris, K. & Newman, K. 1993 page 85)

"Typically, aided speakers have been found to be passive responders who contribute significantly less to the conversational exchange. They exhibit a limited range of communicative functions and rely to a greater extent than do their speaking partners on non-verbal communicative behaviour. They produce a high proportion of yes/no responses and other brief, low-information responses. In their interactions with aided speakers, speaking partners tend to dominate the conversation. They initiate topics more frequently, ask a high proportion of yes/no and forced choice questions, and occupy more of the conversational space." (Buzolich, M. & Lunger, J. 1995)

It is therefore important that we:

Suppose I wanted to help you speak Mandarin Chinese. Suppose I wanted to encourage you to practise the Chinese taught thus far in the establishment. What factors would encourage you to talk to staff in Chinese outside of the classroom? What would put you off? What would make you want to give up entirely?

Please don't let communication problems cause further communication problems.

See Also:

Speech Rate

Anson, D., Moist, P., Przywars, M., Wells, H., Saylor, H., & H. Maxime. (2004).The effects of word completion and word prediction on typing rates using on-screen keyboards. Assistive Technology, Volume 18

Arons, B. (1992) Techniques, perception, and application of time-compressed speech. American Voice I/O Society, pp. 169 – 177

Beukelman, D.R. & P. Mirenda, P. (2005) Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Supporting Children and Adults with Complex Communication Needs. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company, Baltimore, MD.

Beukelman, D.R. & P. Mirenda, P. (1998). Augmentative and alternative communication: Management of severe communication disorders in children and adults. P.H. Brookes Pub. Co.

Bryen, D. (1993). Augmentative Communication Mastery:One approach and some preliminary outcomes. The First Annual Pittsburgh

Employment Conference for Augmented Communicators Proceedings, August 20-22: Shout Press: Pittsburgh

Buzolich, M. & Lunger, J. (1995). Empowering system users in peer training, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 11(1), March 1995, pp 37 - 48

Demasco, P.W., McCoy, K.F., Gong,Y., Pennington, C.A. & Rowe, C. (1989). Towards more intelligent AAC interfaces: The use of natural language processing. RESNA, New Orleans, Louisiana, June 1989.

Demasco, P.W. & McCoy, K.F. (1992). Generating text from compressed input: An intelligent interface for people with severe motor impairments. Communications of the ACM, Volume 35(5), pp. 68 – 78, May

Hoag, L., Bedrosian, J., Johnson, D., Molineux, B. (1994). Variables affecting perceptions of social aspects of the communicative competence of an adult AAC user, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 10 (3), September 1994, pp. 129 - 137.

Higginbotham, D. J., Shane, H., Russell, S. & Caves, K. (2007). Access to AAC: Present, past, and future. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 23 (3), pp. 243 – 257

Hill, K. (2001). The development of a model for automated performance measurement and the establishment of performance indices for augmented communicators under two sampling conditions. Unpublished dissertation. University of Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh, PA.

Hill, K., & Romich, B. (2001). AAC Clinical summary measures for characterizing performance. CSUN Conference Proceedings, Los Angeles, CA.

Hill, K., Romich, B., & Holko, R. (2001). AAC performance: The elements of communication rate. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA), Convention ‘01, New Orleans, LA.

Hill, K., & Romich, B. (2002). A Rate Index for Augmentative and Alternative Communication. International Journal of Speech Technology Volume 5, pp. 57 - 64

Koester, H.H., & Levine, S.P. (1994). Modeling the speed of text entry with a word prediction interface. IEEE Transactions on Rehabilitation Engineering, Volume 2(3), pp. 177 - 187.

Koester, H.H., & Levine, S.P. (1996). Effect of a Word Prediction feature on User Performance. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 12, pp. 155 - 168.

Koester, H.H. & Levine, S.P. (1997). Keystroke-level models for user performance with word prediction. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 13, pp. 239 – 257, December.

Lesher, G.W. & Higginbotham, D.J. (2005). Using web content to enhance augmentative communication. Proceedings of CSUN 2005

Light, J. (1989), Toward a definition of communicative competence for individuals using augmentative and alternative communication systems, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 5(2) , pp. 137 - 144

Light, J. & Binger, C. (1998). Building communicative competence with individuals who use augmentative and alternative communication. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Morris, K. & Newman, K. (1993). Vocabulary to promote social interaction using augmentative communication devices, 14th Southeast Annual Augmentative Communication Conference Proceedings, pp. 85 - 92, Birmingham, Alabama: SEAC

Romich, B.A., & Hill, K.J. (2000). AAC communication rate measurement: Tools and methods for clinical use. RESNA '00 Proceedings, pp. 58 - 60. Arlington, VA: RESNA Press.

Romich, B.A., Hill, K.J., & Spaeth, D.M. (2000). AAC selection rate measurement: Tools and methods for clinical use. RESNA '00 Proceedings, pp. 61 - 63. Arlington, VA: RESNA Press

Romich, B.A., Hill, K.J., & Spaeth, D.M. (2001). AAC selection rate measurement: A method for clinical use based on spelling. RESNA '01 Proceedings, pp. 52 - 54. Arlington, VA: RESNA Press.

Smith, L.E., Higginbotham, D.J., Lesher, G.W., Moulton, B., & Mathy, P. (2006). The development of an automated method for analyzing communication rate in augmentative and alternative communication. Assistive Technology, Volume 18 (1). pp.107 - 121.

Trnka, K., Yarrington, D., McCaw, J., McCoy, K.F., & Pennington, C.A. (2007). The effects of word prediction on communication rate for aac. NAACL, pp. 173 – 176.

Trnka, K., Yarrington, D., McCoy, K.F., & Pennington, C.A. (2006). Topic modeling in fringe word prediction for aac. IUI ’06, pp. 276 – 278

Venkatagiri, H.S. (1993). Efficiency of lexical prediction as a communication acceleration technique. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 9, pp. 161 - 167.

Venkatagiri, H.S. (1995). Techniques for Enhancing Communication Productivity in AAC: A Review of Research. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, Volume 4, pp. 36 – 45.

Wisenburn B. & Higginbotham, D.J. (2009). Participant Evaluations of Rate and Communication Efficacy of an AAC Application Using Natural Language Processing, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 25(2) , pp. 78 - 89

Intelligibility

Drager, K.D.R. & Reichle, J.E. (2001). Effects of Discourse Context on the Intelligibility of Synthesized Speech for Young Adult and Older Adult Listeners, Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, Volume 44, pp. 1052 - 1057, October 2001.

Drager, K.D.R., Clark-Serpentine, E.A., Johnson, K.E. & Roeser, J.L. (2006), Accuracy of Repetition of Digitized and Synthesized Speech for Young Children in Background Noise, American Journal of Speech Language Pathology, Volume 15(2), pp. 155 - 164

Drager, K.D.R., & Finke, E.H. (2012). Intelligibility of Children’s Speech in Digitized Speech, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 28(3), pp. 181 - 189

Hardee, J.B. & Mayhorn, C.B. (2007). Reexamining Synthetic Speech: Intelligibility and the Effects of Age, Task, and Speech Type on Recall, Reviews of Human Factors and Ergonomics, Volume 51(18): pp. 1143 - 1147.

Koul, R. & Hester, K. (2006), Effects of repeated listening experiences on the recognition of synthetic speech by individuals with severe intellectual disabilities. Journal of Speech Language Hearing Research, Volume 49(1), pp. 47 - 57.

Mirenda, P. & Beukelman, D. (1987). A comparison of speech synthesis intelligibility with listeners from three age groups, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 3(3), pp. 120 - 128

Papadopoulos, K., Katemidou, E., Koutsoklenis, A., & Mouratidou, E. (2010). Differences Among Sighted Individuals and Individuals with Visual Impairments in Word Intelligibility Presented via Synthetic and Natural Speech, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 26 (4), pp. 278 - 288

Roring, R.W., Hines, F.G., & Charness, N. (2007). Age Differences in Identifying Words in Synthetic Speech, Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, Volume 49(1), pp. 25 - 31.

Vitevitch M.S. (2002), Naturalistic and Experimental Analyses of Word Frequency and Neighborhood Density Effects in Slips of the Ear, Language and Speech, Volume 45(4), pp. 407 - 434.

Von Berg, S., Panorska A.,, Uken, D., & Qeadan, F. (2009). DECtalk™ and VeriVox™: Intelligibility, Likeability, and Rate Preference Differences for Four Listener Groups, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 25(1), pp. 7 - 18

Our reaction to not understanding must not infringe one of the other fundamentals - that of positive staff attitudes. For a response that evidences less than good practice is likely to demoralize a Learner and may lead to a rejection of the AAC system itself. If you do not understand what a Learner is trying to say then there is no harm in simply saying so in a pleasant manner. Such statements should be accompanied by a request for clarification:

"I'm sorry Susie, my brain is not working well today. I do not understand what you are trying to tell me. Could you try to tell

me again using different words?"

It may be that this strategy fails too. Again, try and alleviate the situation and provide a simpler path for the the Learner to follow:

"I must be stupid today Susie. I still do not understand what you mean. I know what we can try. Can you try and tell me using

just one word what it is about? And we will figure it out together."

It is important that all conversations do not turn into 'teaching opportunities' (see item 10 below) as teaching is best left for specific areas and specific times. While it would appear there is no harm in helping the Learner to produce an intended message that you have just worked out with them, it so often becomes much more than that and can have the effect of alienating the Learner from the system. I have too often witness staff telling a Learner what they 'should have been saying' and then actually rejecting the request! Be careful, sometimes what staff think is helpful is actually quite the reverse!

If you do understand what has been said, even though it may have been said in a rather strange way, do NOT enter 'teacher mode'! Simply respond to the statement as though it had been in perfect English. You have understood and that is fantastic. Celebrate the Learner's achievement is creating a statement from words which was comprehensible, even if not perfect English syntax. Do no tell the Learner the 'correct way to say it' and then make them go through it all again until they have spoken it aloud without a mistake. Worse still, do not do that and then reject the request as well! If you simply must enter 'teacher mode', add the correct form of the the Learner statement to your response without any hint of sarcasm, criticism or belittlement:

LEARNER - Greenhouse now go want

LISTENER - Hi Sally. Oh you want to go to the greenhouse now? That's fine. I guess you need a key.

Would you like me to help you get it?

It is in such interactions that communicative skills are practiced, honed and reinforced. Sadly, sometimes, such interactions only serve to alienate the Learner from the AAC system. Don't let that happen to your Learners.

Communication is important, too important to be made problematic by the actions of others:

"Speech is power in our society. Hence, it should surprise no one that freedom of speech is the first right guaranteed to all Americans in the Bill of Rights. Deprived of speech or another means of effective communication, individuals become invisible. They are simply not heard. They are silenced. And, when people are silenced, others quickly lose sight of their right to be a part of humanity!" (Bryen, D. 1993)

"In the English speaking culture ......, a high value is placed on talking. Indeed, the more one talks, the more one is viewed as a desirable and an active conversational partner. In contrast, individuals who talk very little are often viewed as withdrawn and less competent, making their partners feel uncomfortable." (Hoag, L., Bedrosian, J., Johnson, D., Molineux, B. 1994)

"The goal of any communication system is to increase an individual’s ability to communicate more effectively and efficiently. Typically those who rely on augmentative communication systems communicate at slower rates and with restrictive vocabulary sets. The response by their speaking communication partners is to dominate the conversation by initiating, setting the topic, asking yes/no questions, not pausing long enough to allow the augmentative communicator to respond and closing the conversation. The augmentative communicator then may assume a very passive role in the conversation with reduced social experiences and reduced motivation to use the communication system." (Morris, K. & Newman, K. 1993 page 85)

"Typically, aided speakers have been found to be passive responders who contribute significantly less to the conversational exchange. They exhibit a limited range of communicative functions and rely to a greater extent than do their speaking partners on non-verbal communicative behaviour. They produce a high proportion of yes/no responses and other brief, low-information responses. In their interactions with aided speakers, speaking partners tend to dominate the conversation. They initiate topics more frequently, ask a high proportion of yes/no and forced choice questions, and occupy more of the conversational space." (Buzolich, M. & Lunger, J. 1995)

It is therefore important that we:

- make time to communicate with those Learners using AAC.

- provide opportunity and the time for Learners to respond.

- take turns with Learners.

- respond appropriately in as positive a manner as circumstances allow.

- don't predict what the Learner is going to say or use any other 'speeding-up' strategy unless instructed to do so by the Learner.

- don't show signs of impatience and behaviours we would consider rude in others.

- don't belittle or berate or otherwise devalue the communicative attempt of a Learner.

- don't make fun of a Learner's attempts to communicate. Don't laugh unless they are telling you a joke.

- don't always enter 'teacher mode' on communication by a Learner outside of a didactic environment.

- make a mental note of any concerns we may have about Learner communication and report them to the appropriate staff member concerned out of sight and earshot of the Learner.

- celebrate all Learner communication even if it is not yet at a polished level.

- encourage further Learner communication where possible.

- create an environment in which Learner communication is likely to flourish.

Suppose I wanted to help you speak Mandarin Chinese. Suppose I wanted to encourage you to practise the Chinese taught thus far in the establishment. What factors would encourage you to talk to staff in Chinese outside of the classroom? What would put you off? What would make you want to give up entirely?

Please don't let communication problems cause further communication problems.

See Also:

Speech Rate

Anson, D., Moist, P., Przywars, M., Wells, H., Saylor, H., & H. Maxime. (2004).The effects of word completion and word prediction on typing rates using on-screen keyboards. Assistive Technology, Volume 18

Arons, B. (1992) Techniques, perception, and application of time-compressed speech. American Voice I/O Society, pp. 169 – 177

Beukelman, D.R. & P. Mirenda, P. (2005) Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Supporting Children and Adults with Complex Communication Needs. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company, Baltimore, MD.

Beukelman, D.R. & P. Mirenda, P. (1998). Augmentative and alternative communication: Management of severe communication disorders in children and adults. P.H. Brookes Pub. Co.

Bryen, D. (1993). Augmentative Communication Mastery:One approach and some preliminary outcomes. The First Annual Pittsburgh

Employment Conference for Augmented Communicators Proceedings, August 20-22: Shout Press: Pittsburgh

Buzolich, M. & Lunger, J. (1995). Empowering system users in peer training, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 11(1), March 1995, pp 37 - 48

Demasco, P.W., McCoy, K.F., Gong,Y., Pennington, C.A. & Rowe, C. (1989). Towards more intelligent AAC interfaces: The use of natural language processing. RESNA, New Orleans, Louisiana, June 1989.

Demasco, P.W. & McCoy, K.F. (1992). Generating text from compressed input: An intelligent interface for people with severe motor impairments. Communications of the ACM, Volume 35(5), pp. 68 – 78, May

Hoag, L., Bedrosian, J., Johnson, D., Molineux, B. (1994). Variables affecting perceptions of social aspects of the communicative competence of an adult AAC user, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 10 (3), September 1994, pp. 129 - 137.

Higginbotham, D. J., Shane, H., Russell, S. & Caves, K. (2007). Access to AAC: Present, past, and future. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 23 (3), pp. 243 – 257

Hill, K. (2001). The development of a model for automated performance measurement and the establishment of performance indices for augmented communicators under two sampling conditions. Unpublished dissertation. University of Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh, PA.

Hill, K., & Romich, B. (2001). AAC Clinical summary measures for characterizing performance. CSUN Conference Proceedings, Los Angeles, CA.

Hill, K., Romich, B., & Holko, R. (2001). AAC performance: The elements of communication rate. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA), Convention ‘01, New Orleans, LA.

Hill, K., & Romich, B. (2002). A Rate Index for Augmentative and Alternative Communication. International Journal of Speech Technology Volume 5, pp. 57 - 64

Koester, H.H., & Levine, S.P. (1994). Modeling the speed of text entry with a word prediction interface. IEEE Transactions on Rehabilitation Engineering, Volume 2(3), pp. 177 - 187.

Koester, H.H., & Levine, S.P. (1996). Effect of a Word Prediction feature on User Performance. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 12, pp. 155 - 168.

Koester, H.H. & Levine, S.P. (1997). Keystroke-level models for user performance with word prediction. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 13, pp. 239 – 257, December.

Lesher, G.W. & Higginbotham, D.J. (2005). Using web content to enhance augmentative communication. Proceedings of CSUN 2005

Light, J. (1989), Toward a definition of communicative competence for individuals using augmentative and alternative communication systems, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 5(2) , pp. 137 - 144

Light, J. & Binger, C. (1998). Building communicative competence with individuals who use augmentative and alternative communication. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Morris, K. & Newman, K. (1993). Vocabulary to promote social interaction using augmentative communication devices, 14th Southeast Annual Augmentative Communication Conference Proceedings, pp. 85 - 92, Birmingham, Alabama: SEAC

Romich, B.A., & Hill, K.J. (2000). AAC communication rate measurement: Tools and methods for clinical use. RESNA '00 Proceedings, pp. 58 - 60. Arlington, VA: RESNA Press.

Romich, B.A., Hill, K.J., & Spaeth, D.M. (2000). AAC selection rate measurement: Tools and methods for clinical use. RESNA '00 Proceedings, pp. 61 - 63. Arlington, VA: RESNA Press

Romich, B.A., Hill, K.J., & Spaeth, D.M. (2001). AAC selection rate measurement: A method for clinical use based on spelling. RESNA '01 Proceedings, pp. 52 - 54. Arlington, VA: RESNA Press.

Smith, L.E., Higginbotham, D.J., Lesher, G.W., Moulton, B., & Mathy, P. (2006). The development of an automated method for analyzing communication rate in augmentative and alternative communication. Assistive Technology, Volume 18 (1). pp.107 - 121.

Trnka, K., Yarrington, D., McCaw, J., McCoy, K.F., & Pennington, C.A. (2007). The effects of word prediction on communication rate for aac. NAACL, pp. 173 – 176.

Trnka, K., Yarrington, D., McCoy, K.F., & Pennington, C.A. (2006). Topic modeling in fringe word prediction for aac. IUI ’06, pp. 276 – 278

Venkatagiri, H.S. (1993). Efficiency of lexical prediction as a communication acceleration technique. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 9, pp. 161 - 167.

Venkatagiri, H.S. (1995). Techniques for Enhancing Communication Productivity in AAC: A Review of Research. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, Volume 4, pp. 36 – 45.

Wisenburn B. & Higginbotham, D.J. (2009). Participant Evaluations of Rate and Communication Efficacy of an AAC Application Using Natural Language Processing, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 25(2) , pp. 78 - 89

Intelligibility

Drager, K.D.R. & Reichle, J.E. (2001). Effects of Discourse Context on the Intelligibility of Synthesized Speech for Young Adult and Older Adult Listeners, Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, Volume 44, pp. 1052 - 1057, October 2001.

Drager, K.D.R., Clark-Serpentine, E.A., Johnson, K.E. & Roeser, J.L. (2006), Accuracy of Repetition of Digitized and Synthesized Speech for Young Children in Background Noise, American Journal of Speech Language Pathology, Volume 15(2), pp. 155 - 164

Drager, K.D.R., & Finke, E.H. (2012). Intelligibility of Children’s Speech in Digitized Speech, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 28(3), pp. 181 - 189

Hardee, J.B. & Mayhorn, C.B. (2007). Reexamining Synthetic Speech: Intelligibility and the Effects of Age, Task, and Speech Type on Recall, Reviews of Human Factors and Ergonomics, Volume 51(18): pp. 1143 - 1147.

Koul, R. & Hester, K. (2006), Effects of repeated listening experiences on the recognition of synthetic speech by individuals with severe intellectual disabilities. Journal of Speech Language Hearing Research, Volume 49(1), pp. 47 - 57.

Mirenda, P. & Beukelman, D. (1987). A comparison of speech synthesis intelligibility with listeners from three age groups, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 3(3), pp. 120 - 128

Papadopoulos, K., Katemidou, E., Koutsoklenis, A., & Mouratidou, E. (2010). Differences Among Sighted Individuals and Individuals with Visual Impairments in Word Intelligibility Presented via Synthetic and Natural Speech, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 26 (4), pp. 278 - 288

Roring, R.W., Hines, F.G., & Charness, N. (2007). Age Differences in Identifying Words in Synthetic Speech, Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, Volume 49(1), pp. 25 - 31.

Vitevitch M.S. (2002), Naturalistic and Experimental Analyses of Word Frequency and Neighborhood Density Effects in Slips of the Ear, Language and Speech, Volume 45(4), pp. 407 - 434.

Von Berg, S., Panorska A.,, Uken, D., & Qeadan, F. (2009). DECtalk™ and VeriVox™: Intelligibility, Likeability, and Rate Preference Differences for Four Listener Groups, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 25(1), pp. 7 - 18

TWO: The BEST POLEs

BEST = Best Ever Stimulating Thing

What is it the the Learner loves? Is it sweets/candy, is it a particular game, a TV programme, a particular person? In other words what is the Best Ever Stimulating Thing for a particular individual? Let's start with this as the motivator.

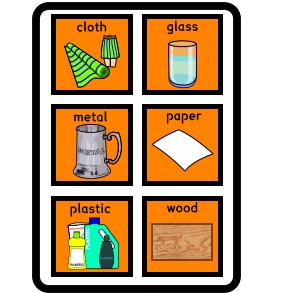

POLE = Person Object Location Event

The BEST thing will be a POLE. POLE is an acronym for Person Object Location or Event. All AAC addresses one of these things and sometimes more than one in the same statement. If we can place a tangible POLE at the end of an AAC action (in other words: provide the Learner with a POLE as a result of a request using an AAC system) then we have a way of moving forward. Not just any sort of POLE! What sort of POLE? Well, a BEST POLE of course.

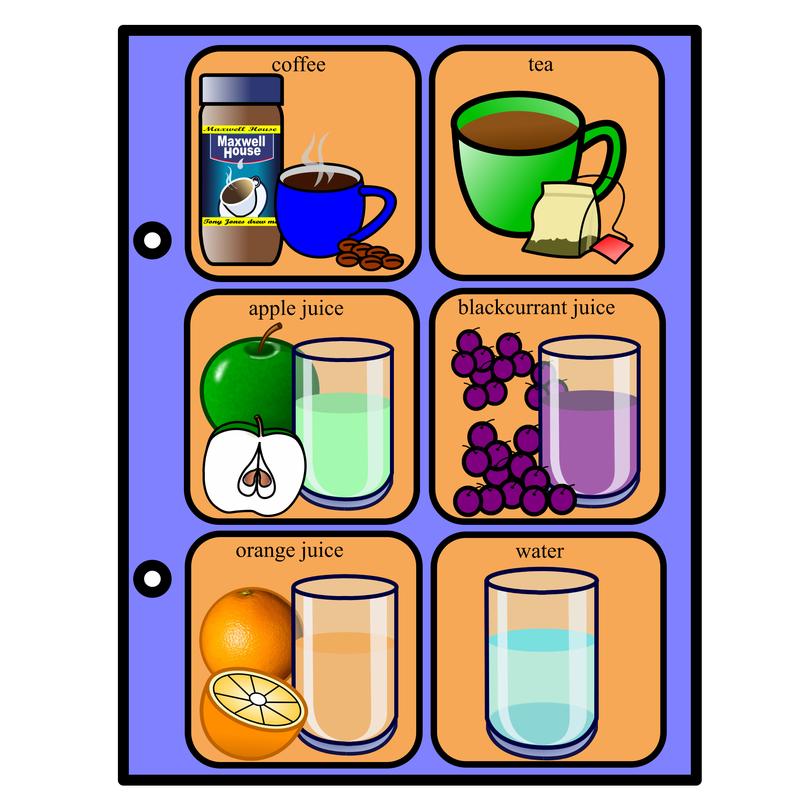

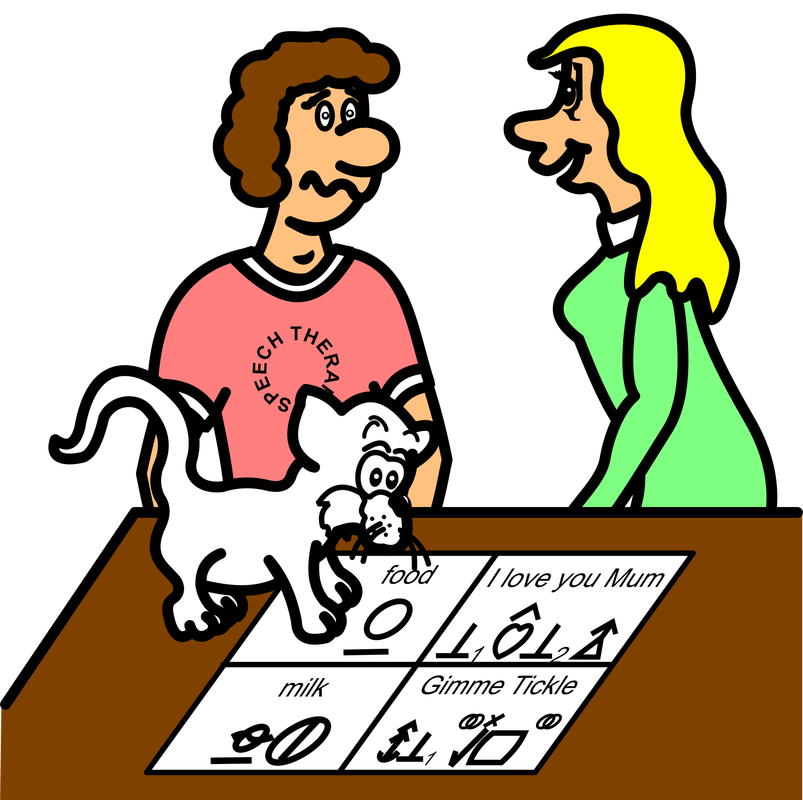

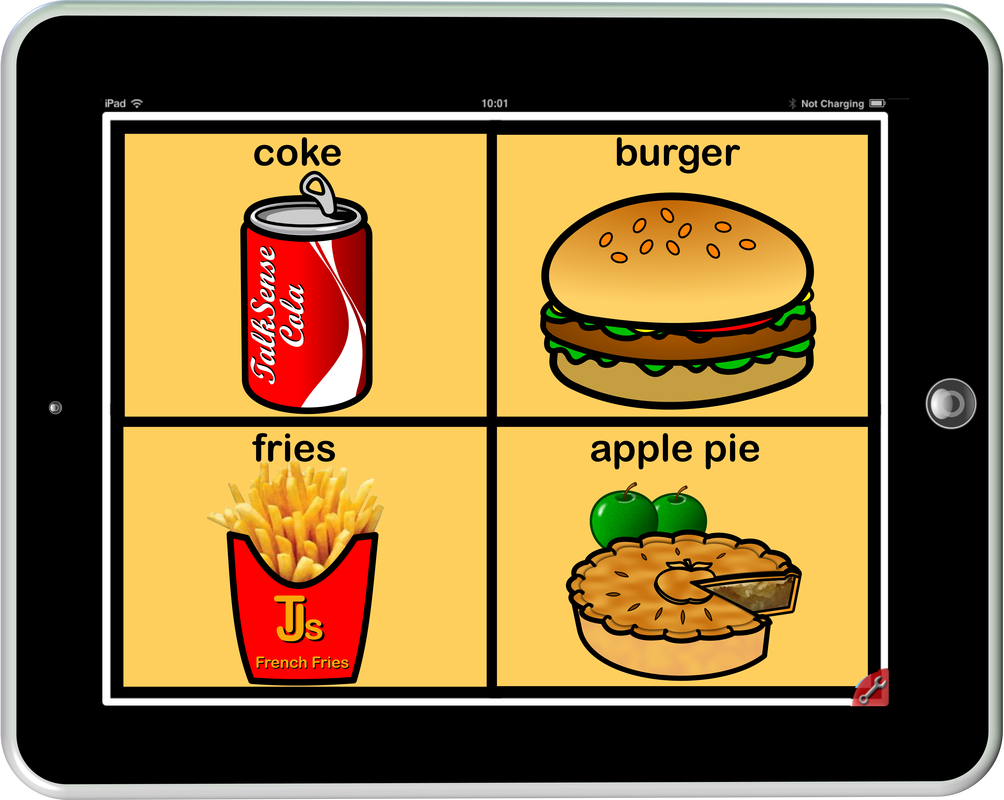

In order to tempt a reluctant Learner to use symbols, work with AAC, or AAC on an SGD (Speech Generating Device), even one that is very simple, may require the Facilitator to make BEST POLEs available. For example, in order that a Learner may come to understand that the use of an SGD results in the ability to obtain a desired reward then the BEST is a great place to start! Some uses of a simple AAC system do not result in a tangible reward: for example, if I were to store 'What time is it please?' on a SSS then the system User is not obtaining a reward from its use (unless the User likes people talking to him/her a lot or is excited by knowing the current time). Beginning Learners of simple AAC systems are more likely to be motivated by concrete POLEs (Persons Objects Locations or Events) than abstract notions. However, a POLE that is motivating to one Learner may not be very motivating to another; one Learner may really love chocolate (object) while another may really like walking in the garden (location) and yet another may really love working with Mary, the Support Assistant (Person). If we can put a BEST POLE at the end of a simple AAC system (in other words, make the receiving of something really motivating to the Learner contingent on the use of a cell on a simple AAC system) then we have a chance of motivating the reluctant User.

Starting simply with AAC work leading to a BEST POLE can not only motivate a reluctant communicator but also help to establish Cause and Effect awareness (see sections on cause and effect on this website) as well as the beginnings of symbolic awareness. While there is always a greater danger of fly-swatting (see fly-swatting later on this web page), this can be overcome (or, at least, highlighted) on movement to and use of more complex AAC systems at some future point.

Can we put a BEST POLE on an AAC system as simple as a one messaging device? Yes! Whatever it is that is motivating to a particular Learner we can surely provide on request at some point. However, there are some BEST POLES that may not be able to be supplied on demand in the classroom: for example, a Learner may love to go swimming, but the swimming pool is across the other side of town and is only available to the establishment on a particular day during a particular time slot.

What is it the the Learner loves? Is it sweets/candy, is it a particular game, a TV programme, a particular person? In other words what is the Best Ever Stimulating Thing for a particular individual? Let's start with this as the motivator.

POLE = Person Object Location Event

The BEST thing will be a POLE. POLE is an acronym for Person Object Location or Event. All AAC addresses one of these things and sometimes more than one in the same statement. If we can place a tangible POLE at the end of an AAC action (in other words: provide the Learner with a POLE as a result of a request using an AAC system) then we have a way of moving forward. Not just any sort of POLE! What sort of POLE? Well, a BEST POLE of course.

In order to tempt a reluctant Learner to use symbols, work with AAC, or AAC on an SGD (Speech Generating Device), even one that is very simple, may require the Facilitator to make BEST POLEs available. For example, in order that a Learner may come to understand that the use of an SGD results in the ability to obtain a desired reward then the BEST is a great place to start! Some uses of a simple AAC system do not result in a tangible reward: for example, if I were to store 'What time is it please?' on a SSS then the system User is not obtaining a reward from its use (unless the User likes people talking to him/her a lot or is excited by knowing the current time). Beginning Learners of simple AAC systems are more likely to be motivated by concrete POLEs (Persons Objects Locations or Events) than abstract notions. However, a POLE that is motivating to one Learner may not be very motivating to another; one Learner may really love chocolate (object) while another may really like walking in the garden (location) and yet another may really love working with Mary, the Support Assistant (Person). If we can put a BEST POLE at the end of a simple AAC system (in other words, make the receiving of something really motivating to the Learner contingent on the use of a cell on a simple AAC system) then we have a chance of motivating the reluctant User.

Starting simply with AAC work leading to a BEST POLE can not only motivate a reluctant communicator but also help to establish Cause and Effect awareness (see sections on cause and effect on this website) as well as the beginnings of symbolic awareness. While there is always a greater danger of fly-swatting (see fly-swatting later on this web page), this can be overcome (or, at least, highlighted) on movement to and use of more complex AAC systems at some future point.

Can we put a BEST POLE on an AAC system as simple as a one messaging device? Yes! Whatever it is that is motivating to a particular Learner we can surely provide on request at some point. However, there are some BEST POLES that may not be able to be supplied on demand in the classroom: for example, a Learner may love to go swimming, but the swimming pool is across the other side of town and is only available to the establishment on a particular day during a particular time slot.

|

Not all our pupils have favourites.

Please do not say that! Yes, they do. It is just that with some individuals the BEST may be very hard to discover. I remember a school that told me they had thought that a particular Learner was not motivated by anything until one day a group of musicians came to the school and this young man was sat near to the tuba player and, every time he played, the young man's face lit up. It was a certain frequency of sounds that was motivating. Talk to Significant Others first - they are likely to know things that may be motivating or, at least, suggest a possible avenue of investigation. I am always concerned when a Learner is self harming as a form of stimulation. Trying to discover something that is more motivating than poking your own eyes, or slapping your own face, or biting yourself (and other such behaviours) is difficult. I once worked with a young lady who would regularly poked herself in her eyes as a form of self stimulation. I found that a really strong fan placed close to her face was the only thing that appeared to be at least as motivating. Providing her with safe control of the fan through a single switch proved very successful and was a platform for further development. |

What if a Learner's BEST is not age appropriate?

So what if it isn't? If it is a favourite it is a place to start and an entry into their world. It is not that everything in the school day will be age inappropriate or that you will be treating them in an age inappropriate way - it is possible to use age inappropriate items in an age appropriate manner. Furthermore, the goal is not to remain with this item, the goal is to use the item as a springboard for moving forward. For me, providing it's ethical and it's a platform for development then its an acceptable tool. However, when the inspectors are around - I wouldn't recommend the use age inappropriate things; they tend not to like them!

See also:

Kavale, K.A., & Forness, S.R. (1986). School Learning, Time and Learning Disabilities: The Disassociated Learner, Journal of Learning Disability, March 1986, Volume 19 (3), pp. 130 - 138.

Mirrett, P.L. & Roberts, J.E. (2003). Early intervention practices and communication intervention strategies for young males with fragile X syndrome, Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, Volume 34(4): pp. 320 - 331.

Tarver, S.G. & Hallahan, D.P. (1974), Attention Deficits In Children With Learning Disabilities; A Review, Journal of Learning Disability, November 1974, Volume 7(9), pp. 560 - 569.

So what if it isn't? If it is a favourite it is a place to start and an entry into their world. It is not that everything in the school day will be age inappropriate or that you will be treating them in an age inappropriate way - it is possible to use age inappropriate items in an age appropriate manner. Furthermore, the goal is not to remain with this item, the goal is to use the item as a springboard for moving forward. For me, providing it's ethical and it's a platform for development then its an acceptable tool. However, when the inspectors are around - I wouldn't recommend the use age inappropriate things; they tend not to like them!

See also:

Kavale, K.A., & Forness, S.R. (1986). School Learning, Time and Learning Disabilities: The Disassociated Learner, Journal of Learning Disability, March 1986, Volume 19 (3), pp. 130 - 138.

Mirrett, P.L. & Roberts, J.E. (2003). Early intervention practices and communication intervention strategies for young males with fragile X syndrome, Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, Volume 34(4): pp. 320 - 331.

Tarver, S.G. & Hallahan, D.P. (1974), Attention Deficits In Children With Learning Disabilities; A Review, Journal of Learning Disability, November 1974, Volume 7(9), pp. 560 - 569.

THREE: Limiting Factors

Whilst a Learner's request for another mouthful of food (while being assisted with eating) is limited by the size of the meal, it is often not the case in other situations; a Learner may go on asking for more and more and cause a bit of a problem for the Significant Others involved. This is especially true if a BEST POLE is involved! (Person Object Location Event)

It is important therefore to set limits on the availability of the POLE rewards that are provided when requested via the use of a simple AAC system. Talksense will illustrate this with a particular example although the same thing can be achieved with any POLE. Let's assume that the particular Learner with whom we are working loves chocolate and the particular BEST for him/her are chocolate buttons.

The first task is to establish a motivational minimum. That is, what is the minimum amount of the POLE that the Learner still finds motivating? If the BEST POLE is a chocolate button, perhaps there is no need need to provide a whole button on request as a half or even a quarter may suffice. Sure that means cutting the buttons carefully into quarters, but the goal here is not to over-feed a Learner (and spoil their appetite for the main meals of the day) but, rather, to:

Limiting the size of the BEST in this way also means that we are not wasting resources on providing complete buttons for a single activation of the system: the relationship is almost inversely proportional - the more limited the POLE the more activations of the system can occur in any one session.

Once a motivational minimum has been established for the BEST POLE, the second task is to set limits on the availability of the POLE in a manner that the Learner will be able to comprehend. This might involve a little subterfuge on the part of the Significant Others involved! For example, continuing with our buttons idea, it is found that the motivational minimum has to be a whole button and it is decided (by the professional team involved) that a limit of just 5 whole buttons in any one session is the maximum amount that can be allowed. A few packets of chocolate buttons are purchased and the contents are kept safely in a refrigerator in a Tupperware or similar container. However, the packets are NOT discarded: each session, the Significant Other concerned takes five buttons and puts them into an empty packet. The packet complete with its five button content is taken into the classroom for use as BEST POLE motivator for the Learner. The packet is emptied onto a plate in front of the Learner. The Significant Other should make a point of noting that there are ONLY five buttons left; "Oh dear! There is only one, two, three, four, five buttons left. Never mind, I'll get some more for tomorrow." The Learner should be clearly able to see the five buttons on the plate. The Learner can be given the packet to see that it is empty. Each time a reward is earned, the Learner is allowed to take a button from the plate. The Learner can see the buttons reducing in number. Each time the Significant Other counts down the remaining buttons such that the Learner is in no doubt as to the finite nature of the reward.

It is important therefore to set limits on the availability of the POLE rewards that are provided when requested via the use of a simple AAC system. Talksense will illustrate this with a particular example although the same thing can be achieved with any POLE. Let's assume that the particular Learner with whom we are working loves chocolate and the particular BEST for him/her are chocolate buttons.

The first task is to establish a motivational minimum. That is, what is the minimum amount of the POLE that the Learner still finds motivating? If the BEST POLE is a chocolate button, perhaps there is no need need to provide a whole button on request as a half or even a quarter may suffice. Sure that means cutting the buttons carefully into quarters, but the goal here is not to over-feed a Learner (and spoil their appetite for the main meals of the day) but, rather, to:

- motivate the Learner into working with the simple AAC system;

- assist the Learner's understanding that using the system is an effective means of controlling the environment.

Limiting the size of the BEST in this way also means that we are not wasting resources on providing complete buttons for a single activation of the system: the relationship is almost inversely proportional - the more limited the POLE the more activations of the system can occur in any one session.

Once a motivational minimum has been established for the BEST POLE, the second task is to set limits on the availability of the POLE in a manner that the Learner will be able to comprehend. This might involve a little subterfuge on the part of the Significant Others involved! For example, continuing with our buttons idea, it is found that the motivational minimum has to be a whole button and it is decided (by the professional team involved) that a limit of just 5 whole buttons in any one session is the maximum amount that can be allowed. A few packets of chocolate buttons are purchased and the contents are kept safely in a refrigerator in a Tupperware or similar container. However, the packets are NOT discarded: each session, the Significant Other concerned takes five buttons and puts them into an empty packet. The packet complete with its five button content is taken into the classroom for use as BEST POLE motivator for the Learner. The packet is emptied onto a plate in front of the Learner. The Significant Other should make a point of noting that there are ONLY five buttons left; "Oh dear! There is only one, two, three, four, five buttons left. Never mind, I'll get some more for tomorrow." The Learner should be clearly able to see the five buttons on the plate. The Learner can be given the packet to see that it is empty. Each time a reward is earned, the Learner is allowed to take a button from the plate. The Learner can see the buttons reducing in number. Each time the Significant Other counts down the remaining buttons such that the Learner is in no doubt as to the finite nature of the reward.

When the rewards are all used, the particular activity (using the simple AAC system) is complete and another activity should commence. The Learner should be shown the empty plate and informed that s/he has eaten all the buttons and there are no more available (the empty packet can be used to reinforce this notion).

What if the Learner continues to request the BEST POLE?

The Learner is shown the empty packet and the plate and is told that the staff member is sorry but there are no more available. However, the Significant Other promises that s/he will buy some more for the next session. Of course, in the next session, the packet will yet again only contain the five buttons!

What if the Learner gets very upset and angry at the lack of BEST POLE?

Hopefully, the above technique will help alleviate such an issue. However, the first time this procedure is attempted, it may be problematic (in this way). The Learner should be prepared for the next task even before the buttons have been eaten: "When all the buttons are gone, we will go and work on the computer." On completion, the Learner is quickly moved to the next task . After this procedure has been used (in various forms) with a Learner, s/he is more likely to come to accept (learn) that there is a finite amount of any pleasurable activity (BEST) to be had and be more accepting of that fact.

Well, it's OK with chocolate buttons you can put onto a plate but what if the BEST POLE is a walk in the school garden that it is not possible to restrict?

With such examples of BEST POLEs it is still important to introduce the concept of restrictions. You can link such POLEs to tokens or tickets that (again) just happen to be available in restricted numbers. For example you might produce five 'walk in the garden' tickets or tokens that the Learner can use at any point during a session by simply asking for it. Each time the Learner asks the ticket or token must be completely removed in a way that precludes its return or re-use (posting in a locked box for example to which the Significant Others involved do not have a key). The Learner can not only now see the tokens or tickets going down but is actively involved in posting them (as in the example) and, thus, can 'sense' the reduction in availability. The Learner may elect to use all the tokens one after another or spread them out to last during a session but, whatever, Significant Others must stick with the scheme and not simply provide more tokens when the set limit has been reached.

What if the Learner continues to request the BEST POLE?

The Learner is shown the empty packet and the plate and is told that the staff member is sorry but there are no more available. However, the Significant Other promises that s/he will buy some more for the next session. Of course, in the next session, the packet will yet again only contain the five buttons!

What if the Learner gets very upset and angry at the lack of BEST POLE?

Hopefully, the above technique will help alleviate such an issue. However, the first time this procedure is attempted, it may be problematic (in this way). The Learner should be prepared for the next task even before the buttons have been eaten: "When all the buttons are gone, we will go and work on the computer." On completion, the Learner is quickly moved to the next task . After this procedure has been used (in various forms) with a Learner, s/he is more likely to come to accept (learn) that there is a finite amount of any pleasurable activity (BEST) to be had and be more accepting of that fact.

Well, it's OK with chocolate buttons you can put onto a plate but what if the BEST POLE is a walk in the school garden that it is not possible to restrict?

With such examples of BEST POLEs it is still important to introduce the concept of restrictions. You can link such POLEs to tokens or tickets that (again) just happen to be available in restricted numbers. For example you might produce five 'walk in the garden' tickets or tokens that the Learner can use at any point during a session by simply asking for it. Each time the Learner asks the ticket or token must be completely removed in a way that precludes its return or re-use (posting in a locked box for example to which the Significant Others involved do not have a key). The Learner can not only now see the tokens or tickets going down but is actively involved in posting them (as in the example) and, thus, can 'sense' the reduction in availability. The Learner may elect to use all the tokens one after another or spread them out to last during a session but, whatever, Significant Others must stick with the scheme and not simply provide more tokens when the set limit has been reached.

You have a swimming ticket above, we cannot possibly provide that on request!

Then do not provide the tickets for such a POLE and do not set up the AAC system so that such a request can be repeated. Only give access to what can be provided.

Some days we might be able to provide staff to go for walks in the school garden but there will be equally other days on which we cannot.

As above, only provide access and tickets for the things that can be provided or, if there is only staff availability for two walks only provide two tickets. Also remember to use the Motivational Minimum in all situations so that a walk around the school garden can be limited to just a few minutes and not an hour or more.

What about other school work?

Repeat requests for POLEs cannot be consecutive; that is, a Learner may not ask for a walk in the garden and then, immediately on returning to class, request the same thing again. The rule is POLE - WORK - POLE - WORK which may be reinforced by a picture or object schedule (See Picture Schedules this page). Indeed, the tickets are best provided as a reward for completion of a set piece of work. If the Learner knows that he will be able to request a particular BEST POLE if s/he completes a (less favoured) task then s/he is more likely to do the task with demonstrating any behaviours that staff may find challenging. Staff should maintain this position consistently so that the Learner is not given mixed messages. If one specific staff member just allows a repetition of a BEST POLE over and over it will effectively dismantle any work that others have achieved. See the section on 'Requesting a Favourite' on this web site.

If access to a BEST POLE is provided through a simple AAC system then it should not be surprising if a Learner begins to ask for it! If a Learner asks then the POLE should be provided. It is counter productive to say such things as, "Oh I haven't time for that now John" or "We have run out of that Jane" or "Jim's playing with that toy now Jack so you can't have it."

If you know in advance that a particular POLE is not going to be available in a particular session then hide or mask or remove that option from the simple AAC system temporarily. See the section on hiding and masking on this web site for more detailed information.

You must decide in advance how much time is allowed per request per POLE! For example, if a Learner requests chocolate and you have found the motivational minimum (the least amount of a POLE which will still satisfy a particular Learner) then simply eating the POLE draws the activity to a close and another request has to be made. If the POLE is a 'walk in the garden' then the motivational minimum may be out of the class, once around the garden and back to class. However, if the POLE is to play with a specific toy how are we to impose a motivational minimum? It has to be something to which the Learner can relate and is outside staff or Learner control. For example, an electronic timer which buzzes or rings when the time is up. There is no one set time which is applicable to all such POLEs, it will vary with the POLE and the Learner and the views of the staff. If you are intending using a ticketing system to limit the amount of requests for a specific POLE then a shorter motivational minimum can mean you can make more tickets available (which means more Learner requests in any one period using the simple AAC system).

Repeat requests for POLEs cannot be consecutive; that is, a Learner may not ask for a walk in the garden and then, immediately on returning to class, request the same thing again. The rule is POLE - WORK - POLE - WORK which may be reinforced by a picture or object schedule (See Picture Schedules this web site). Indeed, the tickets are best provided as a reward for completion of the set piece of work. If the Learner knows that he will be able to request a particular BEST POLE if s/he completes a less favoured task then s/he is more likely to do the task with demonstrating any behaviours that staff may find challenging.

You cannot ticket the playing with a toy, can you? Surely if it is available, it is available!

Well, if the Learner can see it that may be problematic but if it is put away and the staff member ensures that the Learner understand s that s/he will only go and get it out of the cupboard <TICKET> number of times because 's/he is very busy' and Learner can only have it for T time that is measured by D device (Learner should be encouraged to set timer him/herself. The Learner has to understand that playing with the toy is conditional on doing a specific piece of work and that he cannot simple do the work quickly and then play with the toy for the rest of the session. I now apply something like this to my own work routine: if I work for T (time) then I can have M (Minutes) doing something I really like. It works! The trick is too find the Motivational Minimum and the Mission Maximum! The Mission Maximum refers to the maximum amount of work that you can reasonably expect a particular Learner to complete before obtaining a reward. It is directly liked to a Learner's Attention Span and should not exceed this time. However, over an extended period, the goal should be to increase the Maximum while reducing the Minimum! The Mission Maximum should probably not exceed a twenty minute time slot on any one activity. For many Learners it will be significantly less than this period.

What if the Learner refuses to go for work and wants the POLE immediately?

First, the reasons for this should be ascertained. For example, if on entering a classroom the Learner can see the POLE, this may cause an overwhelming desire that is too much for the Learner to overcome. Thus, whenever possible POLEs should be kept out of view until requested. Of course, during the tuition phase it may be necessary to use the POLE as the motivator for the interaction with the simple AAC system. However, during the operational phase, following tuition, the POLEs presence may simply serve as a Learner distractor.

On entering the classroom, the Learner should be shown (indeed be involved in if possible) setting up a picture schedule for the sessions activities. If POLE periods are a part of this schedule then they can be represented by a 'favourites' symbol to indicate that the Learner can make a choice of what s/he wants to do next for a specifically allotted time. It should be clear to the Learner that B is contingent upon A: that is, access to a favourite is contingent upon completion of task A and the issuing of a POLE token or ticket. If a Learner can see that B will follow work on A, s/he will be more likely to comply with A especially if this is enforced across the curriculum by all staff such that the Learner comes to understand that s/he will not have access to a BEST POLE (B) if 'A' is not completed.

Thus, there are ten RULES which may be involved in governing the request for a favourite:

RULE ONE: Investigate BEST POLEs for individual Learners

RULE TWO: Do not provide access to request a favourite item on a simple AAC system if it cannot be supplied.

RULE THREE: Determine the Motivational Minimum (MM) for any POLE. Learner cognizance of MM is important.

RULE FOUR: Set Limits and stick to them.

RULE FIVE: If a Learner makes a request for a favourite POLE then provide it!

RULE SIX: If a POLE cannot be provided on a particular day (or in a particular session) hide or mask the Learner's ability to request it

RULE SEVEN: POLEs are not consecutive: Learner undertakes set work before POLE provision is available.

RULE EIGHT: Determine the Mission Maximum. Learner agreement to (and ability for) Mission Maximum is important.

RULE NINE: During Operational phases, POLEs should be kept out of view (if possible) to avoid Learner Distraction.

RULE TEN: Yes! Rules are meant to be broken but, please, break them with care!

Then do not provide the tickets for such a POLE and do not set up the AAC system so that such a request can be repeated. Only give access to what can be provided.

Some days we might be able to provide staff to go for walks in the school garden but there will be equally other days on which we cannot.

As above, only provide access and tickets for the things that can be provided or, if there is only staff availability for two walks only provide two tickets. Also remember to use the Motivational Minimum in all situations so that a walk around the school garden can be limited to just a few minutes and not an hour or more.

What about other school work?

Repeat requests for POLEs cannot be consecutive; that is, a Learner may not ask for a walk in the garden and then, immediately on returning to class, request the same thing again. The rule is POLE - WORK - POLE - WORK which may be reinforced by a picture or object schedule (See Picture Schedules this page). Indeed, the tickets are best provided as a reward for completion of a set piece of work. If the Learner knows that he will be able to request a particular BEST POLE if s/he completes a (less favoured) task then s/he is more likely to do the task with demonstrating any behaviours that staff may find challenging. Staff should maintain this position consistently so that the Learner is not given mixed messages. If one specific staff member just allows a repetition of a BEST POLE over and over it will effectively dismantle any work that others have achieved. See the section on 'Requesting a Favourite' on this web site.

If access to a BEST POLE is provided through a simple AAC system then it should not be surprising if a Learner begins to ask for it! If a Learner asks then the POLE should be provided. It is counter productive to say such things as, "Oh I haven't time for that now John" or "We have run out of that Jane" or "Jim's playing with that toy now Jack so you can't have it."

If you know in advance that a particular POLE is not going to be available in a particular session then hide or mask or remove that option from the simple AAC system temporarily. See the section on hiding and masking on this web site for more detailed information.

You must decide in advance how much time is allowed per request per POLE! For example, if a Learner requests chocolate and you have found the motivational minimum (the least amount of a POLE which will still satisfy a particular Learner) then simply eating the POLE draws the activity to a close and another request has to be made. If the POLE is a 'walk in the garden' then the motivational minimum may be out of the class, once around the garden and back to class. However, if the POLE is to play with a specific toy how are we to impose a motivational minimum? It has to be something to which the Learner can relate and is outside staff or Learner control. For example, an electronic timer which buzzes or rings when the time is up. There is no one set time which is applicable to all such POLEs, it will vary with the POLE and the Learner and the views of the staff. If you are intending using a ticketing system to limit the amount of requests for a specific POLE then a shorter motivational minimum can mean you can make more tickets available (which means more Learner requests in any one period using the simple AAC system).

Repeat requests for POLEs cannot be consecutive; that is, a Learner may not ask for a walk in the garden and then, immediately on returning to class, request the same thing again. The rule is POLE - WORK - POLE - WORK which may be reinforced by a picture or object schedule (See Picture Schedules this web site). Indeed, the tickets are best provided as a reward for completion of the set piece of work. If the Learner knows that he will be able to request a particular BEST POLE if s/he completes a less favoured task then s/he is more likely to do the task with demonstrating any behaviours that staff may find challenging.

You cannot ticket the playing with a toy, can you? Surely if it is available, it is available!