History for Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties

This page was last updated on the 30th October 2013

"If children don’t learn the way we teach,

We must strive to teach the way they learn."

Ignacio Estrada

"It is essential for the teacher to convey the structure of his/her subject

in a form which the pupils can readily understand"

Michael Wilson (1985)

"History is a cyclic poem written by time upon the memories of man."

Percy Bysshe Shelley

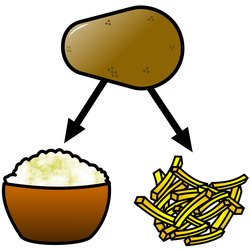

Talksense has witnessed some brilliantly creative lessons concerning history for Individuals experiencing PMLD. These lessons attempt to make the subject relevant to the young people by making the topic more visual, more sensory, and more 'hands-on'. However, the topic of these lessons was still something from the distant past such as the impact of Romans on Britain or an aspect of the First World War for example. While I have always admired the skills and fortitude of the staff concerned in preparing and delivering such sessions, I still feel that such a strategy is focusing on an inappropriate area of history. From my perspective, history for those experiencing PMLD requires to be addressed in an entirely different way: one that is even more relevant to the needs of the individuals and focused on 'historical awareness'. Of course, the staff concerned with the delivery of said sessions would argue that is exactly what we were attempting to do: make the curricular matter relevant to the needs of their Learners by modifying in such ways to make it much more sensory, for example. While they undoubtedly were succeeding in doing that I am uncertain the process could be really be analysed as teaching an 'awareness of history'. As I hope to demonstrate on this page, there are alternate ways of approaching the topic of history for Individuals Experiencing PMLD (IEPMLD). It is an approach which I believe is extremely important for each individual Learner as the concept of a history is a concept which releases a person trapped in the present tense. A knowledge of a past also makes a future possible. Where then do we start? Michael Wilson has suggested (1985, 1992) history should be taught backwards beginning with the present day. I would want to take this (at least) one step further and suggest that history has to begin with individual awareness of space and time and relationships to POLEs (Persons, Objects, Locations, Events) within those spheres. In other words, we cannot assume to begin even with the present day, we have to begin with an individual's awareness of 'now':

" ... in the early stages of introducing history, relevance and appropriateness to meeting pupils' needs must be the first principle"

Sebba, J. (1994)

Judy Sebba's book 'History for All' (1994) is a book aimed at teaching history to pupils with learning difficulties. However, I think it is more aptly named 'History for Some' as it really does not address those Individuals experiencing PMLD. That is not to disparage Professor Sebba who was one of my early mentors and inspirations when I attended a Cambridge Special Education Summer School run by her back in the 1980s: the book is great but it really does not address the concept of history for IEPMLD. Indeed, I could have said the same thing about Michael Wilson's book 'History for pupils with Learning Difficulties' (1985) or Birt's 1976 article which, again, do not address this specific area of concern although they are also very good in their own right. If Professor Sebba, Mr. Wilson and others who title their tomes as 'all-ability' do not address this issue directly where can we get information on approaches to this area of the curriculum?

In the QCA document 'Planning, teaching and assessing the curriculum for pupils with learning difficulties: History' (2009), page 3 reads:

"The subject materials support staff in planning appropriate learning opportunities. The materials do not represent a separate curriculum for pupils with learning difficulties or an alternative to the national curriculum. They demonstrate a process for developing access to the national curriculum and support staff in developing their own curriculum to respond to the needs of their pupils at each key stage. The materials offer one approach to meeting this challenge. Schools may already have effective structures or may wish to adopt different approaches" and goes on to say (page 5), "Staff should teach knowledge, skills and understanding in ways that match and challenge their pupils’ abilities. Staff can modify the history programmes of study for pupils with learning difficulties by:

• choosing material from earlier key stages;

• maintaining and reinforcing previous learning as well as introducing new knowledge, skills and understanding;

• focusing on one aspect or a limited number of aspects, in depth or in outline, of the age-related programmes of study;

• including experiences that let pupils at early stages of learning gain knowledge, skills and understanding of history in the context of

everyday activities;

• helping pupils find out about their personal history through daily routines and sequences, then helping them find out about recent

and past history by using their senses to explore artefacts, sites and reconstructions."

The QCA document is extremely informative and begins to detail how history could be addressed for such a group of people. The document gives an educational establishment a lot of leeway for teaching history to those experiencing PMLD as well as suggesting some excellent possible practices. However, it does not really put any flesh on the bones: to be fair, that was not its intention. However, this webpage will attempt to put the flesh onto the skeletal structure proposed by the QCA. You are free to adopt, adapt, or abrogate any of the suggestions below. I hope you find them useful if only in part. Feel free to contact Talksense using the form provided at the foot of this page to commend, comment or critique the efforts here or send further suggestions that might be added to this page.

On page eight, the QCA document sets out some ideas for activities at History Key Stage One:

The focus of teaching history at key stage 1 may be on giving pupils opportunities to:

• associate the passage of time with a variety of indicators, such as symbols or pictures;

• recognise themselves and familiar people in representations of the very recent past;

• recall events from their recent past with the help of words or pictures or in other ways;

• identify some distinctions between their own past and present, for example, physical differences, changing abilities;

• experience stories of famous people and events from the past;

• recognise the more obvious differences in the way that people lived in the more distant past compared with their own lives;

• use a range of historical sources.

While these ideas are fine for many individuals experiencing Learning Difficulties, they are much more problematic for those experiencing PMLD. While the ideas are all good, we are not told how we know that an individual experiencing PMLD demonstrates conclusively to staff that s/he has 'associated the passage of time with a symbol' or 'recognised themselves' 'in representations of the recent past'. There is a very real danger that staff will ascribe smiling at a picture or a recording as evidence of such recognition for example when several alternate explanations for the smiling behaviour can be given.

History is important - History sets you free!

The concept of a history, of the passage of time and where we are within time is fundamentally important to us all. Those without a grounding in space and time are truly lost to the world. Being trapped in a single moment in time with an accompanying lack of knowledge of the position you occupy in space is truly frightening to the majority of us and yet it must be the experience of many who are classified with the term PMLD. Of course, an individual has to be aware that s/he is lost in space and time to be frightened by it and, therefore, it could be argued that Individuals experiencing PMLD are (thankfully) cushioned from such discomfort. However, it is still a less than ideal state to be occupying.

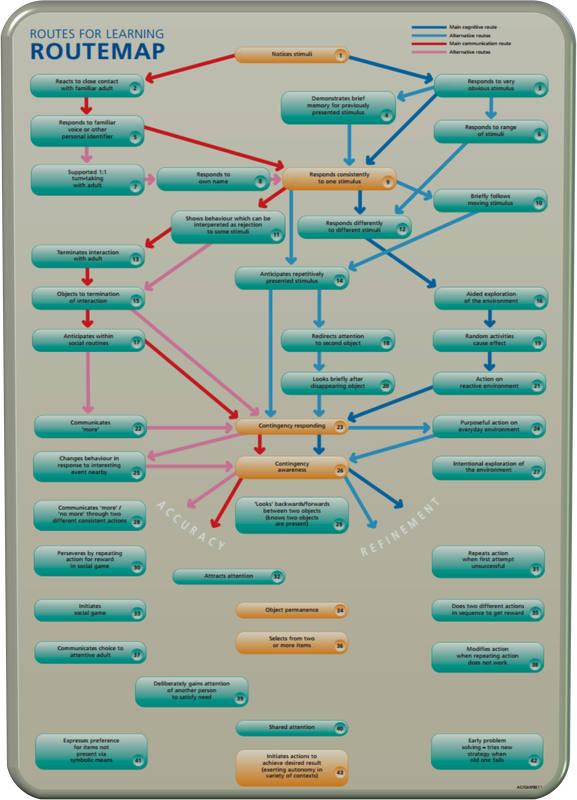

Ware and Donnelly's route map (See below)(See also Ware, J. & Donnelly, V. 2004, 'Assessment for Learning for Pupils with PMLD – the ACCAC Insight Project', PMLD Link, Vol. 16 No.3 Issue 49. Welsh assembly Government, 2006, Routes for Learning) has 'demonstrating a brief memory' in the number four position on their chart and although alternate routes are possible to bypass this 'step', an individual Learner cannot progress very far without some awareness of the passage of time.

Having some awareness of things as they happen is fantastic but, once gone, not retaining that knowledge, negates the possibility of real learning. Therefore, not only do we need to establish an awareness of history but we also need to be able to measure how far that awareness stretches (A minute? An hour? A day, A week? ...). If we can help a Learner establish the concept of the immediate past and measure for how long it stretches (and work to increase that period) then we can set the Learner free to build meaningful experiences of life which will be retained. Thus, establishing a history can set an individual free: free to experience, free to grow and, most importantly, free to learn.

The ideas on this page can assist Significant Others to:

- assess historic awareness;

- build historic awareness;

- calculate the length/range of historic awareness.

Click on image below to download pdf copy.

Ware and Donnelly's route map (See below)(See also Ware, J. & Donnelly, V. 2004, 'Assessment for Learning for Pupils with PMLD – the ACCAC Insight Project', PMLD Link, Vol. 16 No.3 Issue 49. Welsh assembly Government, 2006, Routes for Learning) has 'demonstrating a brief memory' in the number four position on their chart and although alternate routes are possible to bypass this 'step', an individual Learner cannot progress very far without some awareness of the passage of time.

Having some awareness of things as they happen is fantastic but, once gone, not retaining that knowledge, negates the possibility of real learning. Therefore, not only do we need to establish an awareness of history but we also need to be able to measure how far that awareness stretches (A minute? An hour? A day, A week? ...). If we can help a Learner establish the concept of the immediate past and measure for how long it stretches (and work to increase that period) then we can set the Learner free to build meaningful experiences of life which will be retained. Thus, establishing a history can set an individual free: free to experience, free to grow and, most importantly, free to learn.

The ideas on this page can assist Significant Others to:

- assess historic awareness;

- build historic awareness;

- calculate the length/range of historic awareness.

Click on image below to download pdf copy.

Approaches to the teaching of history for those experiencing PMLD.

"The concept of time as hours and minutes is not one that the PMLD student will ever grasp. What can be taught, however, is an awareness of daily routines and a limited sensory of history - what happened yesterday - and the future - what will happen tomorrow."

Cartwright & Wind-Cowie (2005 p.67)

Below are a number of ideas presented for your consideration. You need not accept them all or indeed any of them but, at least, it is hoped they will stimulate further thought and help develop your own ideas in this area. They will not all suit every Significant other involve with a specific Learner: some will be more applicable to Staff while others more applicable to Parents and/or Carers. You must decide. Your thoughts and ideas on the following ideas are welcome and a contact form is provided at the bottom of this page should you wish to use it.

Where possible, the ideas on this page are supported by citing research evidence or other sources of expert testimony. However, it is important that all establishments evaluate practice (especially new practice) for its efficacy. Thus, Talksense would encourage you not simply to add any of the following suggestions into your routine on faith alone (even if it seems like a 'common sense' good ideas!) but to discuss, trial, monitor, review and evaluate any change to practice. If the Learner goal is to develop historic awareness (for example) then it must be shown that the accommodation of a particular ideas into daily practice has achieved this. Unsupported claims for changes in cognition as a result of new interventions are not good practice: for example, how do you know that an Individual Experiencing PMLD (IEPMLD) has developed such awareness as a result of such an intervention? If you can show that a specific behaviour appeared post intervention and that the behaviour:

- appears to be linked to the intervention;

- does not have an alternate explanation as to its cause (other than the desired state of awareness).

For example, is this behaviour just chance? Is it occurring as a result of unconscious staff prompting?

then it would seem fair to assume that the intervention is valid. Your own experience and experimentation is going to be at least as valuable than academic peer-reviewed research especially if staff are not on top of all that is being published in the educational literature (and who is?!). Carl Sagan once said, "extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence" (December 14, 1980. "Encyclopaedia Galactica". Cosmos. Episode 12. PBS) and, perhaps, all claims about interventional practice for IEPMLD should be treated as extraordinary and merely taken on faith alone. Thus, I would encourage you to treat any ideas and or claims made on this page (indeed on any of my pages) with some scepticism and evaluate their efficacy for yourselves in as rigorous a trial as you are able to implement within the constraints of your establishment's current working practices.

The ideas are not presented in any special order of merit: the last is as important (or not important) as the first. At some stage I may re-order them but only to put them in alpha order! Some of the ideas have specific references which are then detailed in the bibliography near the foot of the page: this will be updated as and when I am aware of new sources of information. Some of the ideas also contain blue links: these will open other websites in other windows or take you to other locations on this website. If a new window is opened, you can simply close it when you have finished to be back on this page. If you are taken to another page on this website, use the back button to return here.

It is not the purpose of this webpage to persuade you to swap your current history curricula for the ideas below! Rather, the ideas are there to stimulate your thinking. You do not have to agree or use any of them!: select the ones that appear the most useful and make sense for your practice and for your situation. Any idea presented can be adapted to make it more useful for your particular requirements. If an idea sparks a thought within you then Talksense encourages you to explore that particular cognition!

If you aren't quite sure about a particular idea and have further questions or want further information then why not get in touch using the form at the bottom of this page: it's simple!

Please note: no claim is being made that the list below is exhaustive, we are certain that it isn't! No claim is being made that all of the ideas will work for every one of your Learners: they probably will not! NO claim is being made that any of the ideas will reach every Learner: there will be a few that do not respond. However, while we cannot ever prove that an individual has not gleaned at least something from an experience, we can prove that he has. In this instance, working with the ideas provides experiences which maximises the possibility that an individual will make some sense of them and progress just that little bit further.

Cartwright & Wind-Cowie (2005 p.67)

Below are a number of ideas presented for your consideration. You need not accept them all or indeed any of them but, at least, it is hoped they will stimulate further thought and help develop your own ideas in this area. They will not all suit every Significant other involve with a specific Learner: some will be more applicable to Staff while others more applicable to Parents and/or Carers. You must decide. Your thoughts and ideas on the following ideas are welcome and a contact form is provided at the bottom of this page should you wish to use it.

Where possible, the ideas on this page are supported by citing research evidence or other sources of expert testimony. However, it is important that all establishments evaluate practice (especially new practice) for its efficacy. Thus, Talksense would encourage you not simply to add any of the following suggestions into your routine on faith alone (even if it seems like a 'common sense' good ideas!) but to discuss, trial, monitor, review and evaluate any change to practice. If the Learner goal is to develop historic awareness (for example) then it must be shown that the accommodation of a particular ideas into daily practice has achieved this. Unsupported claims for changes in cognition as a result of new interventions are not good practice: for example, how do you know that an Individual Experiencing PMLD (IEPMLD) has developed such awareness as a result of such an intervention? If you can show that a specific behaviour appeared post intervention and that the behaviour:

- appears to be linked to the intervention;

- does not have an alternate explanation as to its cause (other than the desired state of awareness).

For example, is this behaviour just chance? Is it occurring as a result of unconscious staff prompting?

then it would seem fair to assume that the intervention is valid. Your own experience and experimentation is going to be at least as valuable than academic peer-reviewed research especially if staff are not on top of all that is being published in the educational literature (and who is?!). Carl Sagan once said, "extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence" (December 14, 1980. "Encyclopaedia Galactica". Cosmos. Episode 12. PBS) and, perhaps, all claims about interventional practice for IEPMLD should be treated as extraordinary and merely taken on faith alone. Thus, I would encourage you to treat any ideas and or claims made on this page (indeed on any of my pages) with some scepticism and evaluate their efficacy for yourselves in as rigorous a trial as you are able to implement within the constraints of your establishment's current working practices.

The ideas are not presented in any special order of merit: the last is as important (or not important) as the first. At some stage I may re-order them but only to put them in alpha order! Some of the ideas have specific references which are then detailed in the bibliography near the foot of the page: this will be updated as and when I am aware of new sources of information. Some of the ideas also contain blue links: these will open other websites in other windows or take you to other locations on this website. If a new window is opened, you can simply close it when you have finished to be back on this page. If you are taken to another page on this website, use the back button to return here.

It is not the purpose of this webpage to persuade you to swap your current history curricula for the ideas below! Rather, the ideas are there to stimulate your thinking. You do not have to agree or use any of them!: select the ones that appear the most useful and make sense for your practice and for your situation. Any idea presented can be adapted to make it more useful for your particular requirements. If an idea sparks a thought within you then Talksense encourages you to explore that particular cognition!

If you aren't quite sure about a particular idea and have further questions or want further information then why not get in touch using the form at the bottom of this page: it's simple!

Please note: no claim is being made that the list below is exhaustive, we are certain that it isn't! No claim is being made that all of the ideas will work for every one of your Learners: they probably will not! NO claim is being made that any of the ideas will reach every Learner: there will be a few that do not respond. However, while we cannot ever prove that an individual has not gleaned at least something from an experience, we can prove that he has. In this instance, working with the ideas provides experiences which maximises the possibility that an individual will make some sense of them and progress just that little bit further.

Idea One: Multi-Sensory Referencing

"While they were saying among themselves it cannot be done, it was done."

Helen Keller

"I do not want the peace which passeth understanding, I want the understanding

which bringeth peace."

Helen Keller

Multi-Sensory Referencing is a didactic system that seeks to develop awareness of self in time and space in order to raise cognition and understanding of the world as it is experienced. It is not a single approach but comprises a range of techniques that are used together to form a holistic system. The techniques include Spatial and Temporal Sensory Referencing, Sensory Cueing (often confused with Objects Of Reference), Environmental Engineering, creating a responsive environment, Tangible Symbol development, and Objects Of Reference.

"I realised that these pupils were at the simplest levels of development and needed an education that gave them the opportunity to reach

out and sense the world around. A more formal education had to wait patiently until they were ready"

Flo Longhorn (2010) PMLD Link, Vol. 22, 2 issue 66 page 2

There is a complete page within this website dedicated to the exploration of MSR, please click on the image above left to move there. MSR assists individual Learners to position themselves in time and space, to recall prior POLEs (People, Objects, Locations, and Events) through a range of techniques. As such, it is a system that can assist in the creation of a personal history, a necessary beginning in the learning of history. Please take a look at this page and return here for more ideas.

Helen Keller

"I do not want the peace which passeth understanding, I want the understanding

which bringeth peace."

Helen Keller

Multi-Sensory Referencing is a didactic system that seeks to develop awareness of self in time and space in order to raise cognition and understanding of the world as it is experienced. It is not a single approach but comprises a range of techniques that are used together to form a holistic system. The techniques include Spatial and Temporal Sensory Referencing, Sensory Cueing (often confused with Objects Of Reference), Environmental Engineering, creating a responsive environment, Tangible Symbol development, and Objects Of Reference.

"I realised that these pupils were at the simplest levels of development and needed an education that gave them the opportunity to reach

out and sense the world around. A more formal education had to wait patiently until they were ready"

Flo Longhorn (2010) PMLD Link, Vol. 22, 2 issue 66 page 2

There is a complete page within this website dedicated to the exploration of MSR, please click on the image above left to move there. MSR assists individual Learners to position themselves in time and space, to recall prior POLEs (People, Objects, Locations, and Events) through a range of techniques. As such, it is a system that can assist in the creation of a personal history, a necessary beginning in the learning of history. Please take a look at this page and return here for more ideas.

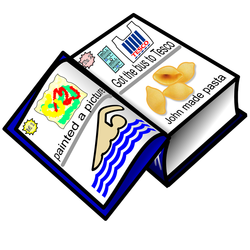

Idea Two: Memory Books

A Memory Book is a form of 'diary' that can assist the Learner with the concept of time. However, a Memory Book is NOT:

- a scrapbook full of old memories such as pictures of childhood or

momentous moments of an individual life.

- a symbolic timetable of an individual's week.

- a home/school diary.

- a written log of a Learner's day.

Items are pasted into the Memory Book to represent each session or part of a Learner's day.

Once begun, it becomes possible for the Learner to 'look back' at what happened within a particular period of time.

A Memory Book can utilise an existing (sturdy) diary or can be created from a ring binder with blank pages divided into time periods. When Items have been attached to pages, the Memory Book tends to thicken and so fixed books (such as diaries) are not necessarily as useful as loose leaf books (such as ring binders) which allow for pages to grow in stature! However, it is possible to use existing diaries.

Memory Books are suitable for children, young people, adults and the elderly. Anyone who has severe cognitive deficits for whatever reason may benefit from their use. This website has an entire page devoted to the exploration of the use of Memory Books, please click on the image above left to go there. Please take a look at this page and return here for more ideas in developing the concept of history for those experiencing PMLD.

An individual is assisted to build a memory book during each session of their day. For example:

- At the end of an art class the individual might be assisted to take a piece of what they have create and fix it into their book.

- After a trip to a supermarket, a bus ticket, a piece of a shopping bag, and the wrapping from an item purchased may be affixed.

- Following a food preparation session the individual Learner can attached some dried items of food that were used in the

preparation of the meal.

- Immediately after a game of sport, the Learner can be assisted to paste in a digital photograph of that particular sporting activity.

It is important that:

- the Learner him/herself be involved in attaching the items into the Memory book. Staff must NOT do it on the Learner's behalf;

- the Learner explores the entry in a sensory manner: through, sight, feel, smell, taste and even sound if appropriate!

- entries into the memory book are items that have meaning for the Learner;

- entries into the Memory Book are items that were part of the session which is being referenced.

- Significant Others (parents/carers) review the Memory Book often with the Learner.

- Significant Others (parents/carers) assist the Learner to make entries into the Memory book for periods outside of the

educational day/week.

- each session ends with a five to ten minute period in which the Learner is assisted to make a Memory Book entry.

- staff make use of the Memory Book as a part of a regular review of recent events with the Learner.

- each Memory Book is seen as the property of the Learner and not of the school or college or centre.

It is important NOT to:

- make written entries into the Memory Book (all staff take note!). All writing must be kept to an absolute minimum and must only

be used to explain the meaning of an entry to a Significant Other who may be sitting reviewing the entries later that day.

- simply use a timetable symbol as the entry of a particular session. Adding a time-table symbol creates a copy of the timetable and,

as such, is a complete waste of time and effort.

- make entries on behalf of a Learner. The Learner must be assisted to make entries him/herself.

Memory Books can be used to establish the concept of a history of (recent) events with a Learner using a medium in which the Learner can cope cognitively. It is a diary of experiences referenced through real items and created by the Learner him/herself (with assistance from stance according to individual need).

- a scrapbook full of old memories such as pictures of childhood or

momentous moments of an individual life.

- a symbolic timetable of an individual's week.

- a home/school diary.

- a written log of a Learner's day.

Items are pasted into the Memory Book to represent each session or part of a Learner's day.

Once begun, it becomes possible for the Learner to 'look back' at what happened within a particular period of time.

A Memory Book can utilise an existing (sturdy) diary or can be created from a ring binder with blank pages divided into time periods. When Items have been attached to pages, the Memory Book tends to thicken and so fixed books (such as diaries) are not necessarily as useful as loose leaf books (such as ring binders) which allow for pages to grow in stature! However, it is possible to use existing diaries.

Memory Books are suitable for children, young people, adults and the elderly. Anyone who has severe cognitive deficits for whatever reason may benefit from their use. This website has an entire page devoted to the exploration of the use of Memory Books, please click on the image above left to go there. Please take a look at this page and return here for more ideas in developing the concept of history for those experiencing PMLD.

An individual is assisted to build a memory book during each session of their day. For example:

- At the end of an art class the individual might be assisted to take a piece of what they have create and fix it into their book.

- After a trip to a supermarket, a bus ticket, a piece of a shopping bag, and the wrapping from an item purchased may be affixed.

- Following a food preparation session the individual Learner can attached some dried items of food that were used in the

preparation of the meal.

- Immediately after a game of sport, the Learner can be assisted to paste in a digital photograph of that particular sporting activity.

It is important that:

- the Learner him/herself be involved in attaching the items into the Memory book. Staff must NOT do it on the Learner's behalf;

- the Learner explores the entry in a sensory manner: through, sight, feel, smell, taste and even sound if appropriate!

- entries into the memory book are items that have meaning for the Learner;

- entries into the Memory Book are items that were part of the session which is being referenced.

- Significant Others (parents/carers) review the Memory Book often with the Learner.

- Significant Others (parents/carers) assist the Learner to make entries into the Memory book for periods outside of the

educational day/week.

- each session ends with a five to ten minute period in which the Learner is assisted to make a Memory Book entry.

- staff make use of the Memory Book as a part of a regular review of recent events with the Learner.

- each Memory Book is seen as the property of the Learner and not of the school or college or centre.

It is important NOT to:

- make written entries into the Memory Book (all staff take note!). All writing must be kept to an absolute minimum and must only

be used to explain the meaning of an entry to a Significant Other who may be sitting reviewing the entries later that day.

- simply use a timetable symbol as the entry of a particular session. Adding a time-table symbol creates a copy of the timetable and,

as such, is a complete waste of time and effort.

- make entries on behalf of a Learner. The Learner must be assisted to make entries him/herself.

Memory Books can be used to establish the concept of a history of (recent) events with a Learner using a medium in which the Learner can cope cognitively. It is a diary of experiences referenced through real items and created by the Learner him/herself (with assistance from stance according to individual need).

Idea Three: Adverse Reactions

Individuals experiencing PMLD often have a strong startle reflex:

- Johnny hits a switch and a toy rocket launcher makes a bang or a stationary toy

suddenly springs into life;

- Johnny startles and his face shows signs of upset;

- Staff notice Johnny's state and remove the offending toy stating that he had an

adverse reactions and they will find him something which will not scare him so.

While, seemingly, the staff are acting in the best interests of Johnny, they are missing a unique opportunity! If Johnny's reaction is not life threatening or likely to bring about a seizure or some other misfortune then it may be a better strategy to encourage Johnny to continue and to monitor his reactions over time.

Let us suppose that Johnny has a switch attached to a POLE event (Person Object Location Event) that causes him to startle as stated above. The first time he hits the switch he startles. The second time he hits the switch he startles. The third time, however, there is an obvious reduction in Johnny's reaction and by the fourth switch activation there is no discernable startle reaction whatsoever. What does this tell us? What can we state about Johnny after observing his behaviour? Surely it must suggest that Johnny has become accustomed to the POLE action caused by activating the switch. If this is the case, how has he become accustomed? It is not by magic! He must be anticipating what is about to happen and if he is anticipating then:

- he must have linked the switch to the event (cause and effect - see cause and effect this page)

- he must be remembering previously encountered experiences.

Continuing with the example of Johnny. Let us suppose he interacts with the switch and the toy for ten minutes during the session, after which the switch and toy are removed so that he might participate in a group activity. Approximately 30 minutes later, the switch and the toy are represented and Johnny begins activates the switch once more. The first time he startles. However, unlike his first experience, the startle response is absent on his second switch activation. Furthermore, when Johnny returns to the classroom after lunch and works wit the switch and the toy for a third session there is no startle response at all. What can we now begin to assume?

Suppose Johnny works with toy the following day still with no adverse reaction then we let two days pass before we reintroduce the same toy to Johnny: still no adverse reaction, Indeed, it seems to require a week of absence form the toy before the startle reflex returns as strong as it was initially. Does this not suggest to you an observable means of establishing the retention of an event for an Individual experiencing PMLD? Not only can we claim that Johnny is remembering but we can also measure for how long he can remember!

Of course, we are not setting out to deliberately startle any individual nor is this being recommended but if it happens in the course of a daily event (and it is my experience at least that it does) then we can turn the situation to our advantage as well as helping Johnny to work with a toy which we believe he will ultimately find pleasurable and also has educational merit.

- Johnny hits a switch and a toy rocket launcher makes a bang or a stationary toy

suddenly springs into life;

- Johnny startles and his face shows signs of upset;

- Staff notice Johnny's state and remove the offending toy stating that he had an

adverse reactions and they will find him something which will not scare him so.

While, seemingly, the staff are acting in the best interests of Johnny, they are missing a unique opportunity! If Johnny's reaction is not life threatening or likely to bring about a seizure or some other misfortune then it may be a better strategy to encourage Johnny to continue and to monitor his reactions over time.

Let us suppose that Johnny has a switch attached to a POLE event (Person Object Location Event) that causes him to startle as stated above. The first time he hits the switch he startles. The second time he hits the switch he startles. The third time, however, there is an obvious reduction in Johnny's reaction and by the fourth switch activation there is no discernable startle reaction whatsoever. What does this tell us? What can we state about Johnny after observing his behaviour? Surely it must suggest that Johnny has become accustomed to the POLE action caused by activating the switch. If this is the case, how has he become accustomed? It is not by magic! He must be anticipating what is about to happen and if he is anticipating then:

- he must have linked the switch to the event (cause and effect - see cause and effect this page)

- he must be remembering previously encountered experiences.

Continuing with the example of Johnny. Let us suppose he interacts with the switch and the toy for ten minutes during the session, after which the switch and toy are removed so that he might participate in a group activity. Approximately 30 minutes later, the switch and the toy are represented and Johnny begins activates the switch once more. The first time he startles. However, unlike his first experience, the startle response is absent on his second switch activation. Furthermore, when Johnny returns to the classroom after lunch and works wit the switch and the toy for a third session there is no startle response at all. What can we now begin to assume?

Suppose Johnny works with toy the following day still with no adverse reaction then we let two days pass before we reintroduce the same toy to Johnny: still no adverse reaction, Indeed, it seems to require a week of absence form the toy before the startle reflex returns as strong as it was initially. Does this not suggest to you an observable means of establishing the retention of an event for an Individual experiencing PMLD? Not only can we claim that Johnny is remembering but we can also measure for how long he can remember!

Of course, we are not setting out to deliberately startle any individual nor is this being recommended but if it happens in the course of a daily event (and it is my experience at least that it does) then we can turn the situation to our advantage as well as helping Johnny to work with a toy which we believe he will ultimately find pleasurable and also has educational merit.

Idea Four: BRT (BEST Reward Test)

A BEST Reward Test is a means to give some indication the extent of an individual's memory at more than a simple chance level. BEST stands for Best Ever Stimulating Thing.

BEST = Best Ever Stimulating Thing

What is it the the Learner loves? Is it sweets/candy? Is it a particular game, a TV programme, a particular person? In other words, what is the Best Ever Stimulating Thing for a particular individual? Let's start working with this BEST as the motivator.

POLE = Person Object Location Event

The BEST thing will be a POLE. POLE is an acronym for Person, Object, Location, or Event. If we can place a tangible POLE at the end of a Learner action (For example: provide the Learner with a POLE as a result of a request using an Augmentative Communication system) then we have a way of moving forward. Not just any sort of POLE! What sort of POLE? Well, a BEST POLE of course.

Here are some ideas:

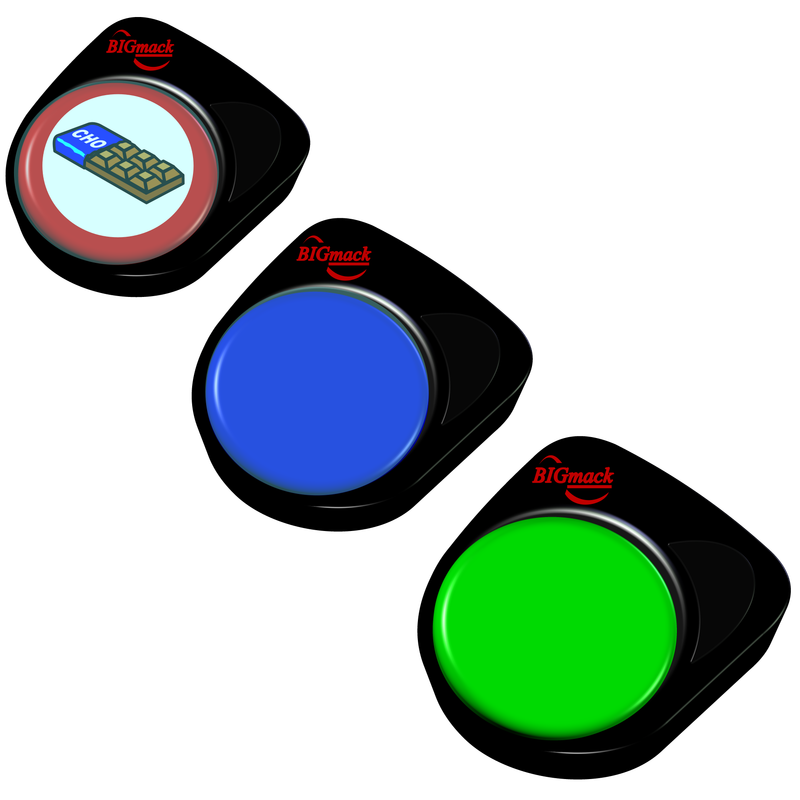

For those that can touch: Start with a single BIGmack (or equivalent device). Label it with an appropriate symbol or a sensory surface for the Learner's BEST POLE. By demonstrating, modelling and even accidental access, show the Learner that the activation of the device leads to the provision of their BEST POLE. We want the Learner to make the connection between the BIGmack and the POLE but, even though a particular Learner may activate such a BIGmack repeatedly, it is difficult to establish intentionality: the Learner may be activating the system accidentally for example or just exploring (and thus repeatedly activating) the BIGmack as it has been placed in the Learner's reach.

The use of a single BIGmack is the teaching phase. Once we have a Learner activating a BIGMack to obtain a reward (for whatever reason) it becomes necessary to step up the level of difficulty of the task very slightly to ascertain Learner cognisance. If we add a second BIGmack of a different colour (New BIGmacks come with four different colour interchangeable tops) which says "Please remove the BIGmacks for five minutes" in a voice that is also neutral in tone (such that the sound itself does not become a motivator) complete with a different symbolic label or sensory surface (or a lack of symbolic label or sensory surface) and both BIGmacks are placed within the reach of the Learner, we can now assess if the Learner activates the BIGmack which leads to a BEST reward more than the one which leads to their removal. Thus, as you can see, the activation of the original BIGmack leads to a reward while the activation of the other different BIGmack leads to their removal (and therefore no possibility of BEST) for a specified period of time. Initially, to assist the Learner in achieving success, the BEST BIGmack can be positioned on the preferred side of the Learner such that it is likely that this is the one that will be activated. However, before moving to the next stage, it is important to swap the BIGmacks about such that, in wherever order they are positioned, the Learner still achieves success.

Once there has been success with two BIGmacks, step it up once more to three! Two of the BIGmacks lead to the removal of the system for a specified time period and only the original BIGmack obtains the BEST POLE. If the Learner learns to activate the BEST BIGmack no matter what position it occupies relative to the other two then there are a number of things that we might justifiably claim:

No, s/he's not doing that at all! S/he is just attracted to red BIGmacks and is going for the red one each time - no recall is taking place.

OK, that is a good point. So what should we do about that possibility? If it is known in advance that the Learner is attracted to the colour red then we should not use red as the BEST BIGMack but rather for the distractors!

We haven't got three BIGmacks!

It is my advice that every classroom should have at least three BIGmacks (AbleNet are not sponsoring me to say that!) available for use. However, it does not have to be a BIGmack system, it can be any SGD (Speech Generating Device) or a device that has at least three cells (the other cells can remain blank). Alternatively, you can use the Microsoft PowerPoint system on a touch screen.

It is important that:

BEST = Best Ever Stimulating Thing

What is it the the Learner loves? Is it sweets/candy? Is it a particular game, a TV programme, a particular person? In other words, what is the Best Ever Stimulating Thing for a particular individual? Let's start working with this BEST as the motivator.

POLE = Person Object Location Event

The BEST thing will be a POLE. POLE is an acronym for Person, Object, Location, or Event. If we can place a tangible POLE at the end of a Learner action (For example: provide the Learner with a POLE as a result of a request using an Augmentative Communication system) then we have a way of moving forward. Not just any sort of POLE! What sort of POLE? Well, a BEST POLE of course.

Here are some ideas:

For those that can touch: Start with a single BIGmack (or equivalent device). Label it with an appropriate symbol or a sensory surface for the Learner's BEST POLE. By demonstrating, modelling and even accidental access, show the Learner that the activation of the device leads to the provision of their BEST POLE. We want the Learner to make the connection between the BIGmack and the POLE but, even though a particular Learner may activate such a BIGmack repeatedly, it is difficult to establish intentionality: the Learner may be activating the system accidentally for example or just exploring (and thus repeatedly activating) the BIGmack as it has been placed in the Learner's reach.

The use of a single BIGmack is the teaching phase. Once we have a Learner activating a BIGMack to obtain a reward (for whatever reason) it becomes necessary to step up the level of difficulty of the task very slightly to ascertain Learner cognisance. If we add a second BIGmack of a different colour (New BIGmacks come with four different colour interchangeable tops) which says "Please remove the BIGmacks for five minutes" in a voice that is also neutral in tone (such that the sound itself does not become a motivator) complete with a different symbolic label or sensory surface (or a lack of symbolic label or sensory surface) and both BIGmacks are placed within the reach of the Learner, we can now assess if the Learner activates the BIGmack which leads to a BEST reward more than the one which leads to their removal. Thus, as you can see, the activation of the original BIGmack leads to a reward while the activation of the other different BIGmack leads to their removal (and therefore no possibility of BEST) for a specified period of time. Initially, to assist the Learner in achieving success, the BEST BIGmack can be positioned on the preferred side of the Learner such that it is likely that this is the one that will be activated. However, before moving to the next stage, it is important to swap the BIGmacks about such that, in wherever order they are positioned, the Learner still achieves success.

Once there has been success with two BIGmacks, step it up once more to three! Two of the BIGmacks lead to the removal of the system for a specified time period and only the original BIGmack obtains the BEST POLE. If the Learner learns to activate the BEST BIGmack no matter what position it occupies relative to the other two then there are a number of things that we might justifiably claim:

- the Learner is retaining and recalling the function of a specific (distinct by symbolic label and colour) BIGmack;

- the Learner is discriminating between the symbols and or the colours;

- the Learner has remembered an event from recent history

No, s/he's not doing that at all! S/he is just attracted to red BIGmacks and is going for the red one each time - no recall is taking place.

OK, that is a good point. So what should we do about that possibility? If it is known in advance that the Learner is attracted to the colour red then we should not use red as the BEST BIGMack but rather for the distractors!

We haven't got three BIGmacks!

It is my advice that every classroom should have at least three BIGmacks (AbleNet are not sponsoring me to say that!) available for use. However, it does not have to be a BIGmack system, it can be any SGD (Speech Generating Device) or a device that has at least three cells (the other cells can remain blank). Alternatively, you can use the Microsoft PowerPoint system on a touch screen.

It is important that:

- the BIGmacks are labelled with either symbols or sensory surfaces (make sensory switch caps for example);

- staff model required behaviours such that a Learner can experience the staff member obtaining a BEST through a particular action;

- only one of any set of BIGmacks presented leads to a BEST reward: others should lead to removal of activity;

- initially, we assist the Learner to succeed. We can position the rewarding BEST BIGmack in a preferred position for example;

- the reward follows the rules for BEST as outlined on the fundamentals page (follow link to go there).

- should this approach appear to fail, the Learner can be assisted to make an activation through hand-under-hand physical prompting.

|

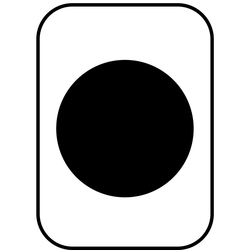

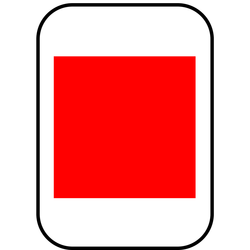

You might provide an intermediate stage in which the BIGmacks are presented but only one has a symbol attached as depicted in the illustration right. We are not trying to trick the Learner or make it difficult for him or her: we want the Learner to succeed and therefore you can provide as may intermediate stages as you think fit that will assist Learners on their way. Initially, for example, you might put the 'correct' BIGmack in the Learner's favoured position and then move it one place from there. You may also start with the Learner's preferred colour but this must be changed before the final stage of the procedure.

If a Learner can select (on more than one occasion) the correct BIGmack by selecting a colour and or a symbol out of three choice of symbol and colour then it is party time! It's a momentous achievement. Suppose all three BIGmacks are the same colour and all have symbols and yet the Learner still selects the BEST on more than one occasion and with the BIGmacks in different relative position on each occasion - what can we claim then? The Learner must be discriminating between symbols and if a Learner can do that then the sky is the limit. Pat yourself on the back for a job well done!!! |

For those that cannot touch (but can see): One technique is to prepare at least five cards. Each of the cards depicts a different random shape which has no specific meaning. One of the cards is selected to represent the BEST. This is taught to the individual Learner through a combination of association and modelling (see below) until the Learner can select the card (without error) using a their own specific yes/no response in a 'blind' staff presentation.

In a blind presentation, the staff member concerned shuffles the cards and then presents them, one by one, face towards the Learner such that the Learner can see the card but the staff member cannot. In this way there cannot be any unintentional cueing of the Learner as to when to respond. The Staff member continues to present the cards one by one, returning rejected cards to the back of the pack, until the Learner provides his/her 'yes response' to indicate that is the one selected. Only at this point can the staff member look at the face of the card at the front of the pack. If it is the card that has been selected as BEST then the reward must be provided. If it is any other card, then the opportunity to obtain BEST is withdrawn for a specified time (at least five minutes) while something else is done.

You're joking! That's way too advanced. My Learner will simply ignore the cards altogether.

Of course it is! That is why you have to begin with the single BEST card and teach the Learner it's meaning. Once you believe that the Learner has a grasp of the concept then you can add a second card into the mix and see if the Learner can select the one that represents the BEST. Selection of the other card should always lead to the withdrawal of the possibility of obtaining BEST for a specified time period.

You're joking! My Learner cannot associate a card with a BEST. She'll just sit and rock.

You may be correct but what are you doing in place of this? How do you know if you do not try? Each time you give the Learner the BEST for a whole term ensure that the card is presented just before. You could make the card shape tactile by drawing around the shape with a glue gun to raise its borders and then filling the shape with a sensory surface such as sand and glue and, when set, painting it the appropriate colour. After a whole term you could try to ascertain if the Learner goes for that particular card when mixed in with a couple of plain cards. If that works then ad a small dot to one of the plain cards and see if the Learner can still do it. Gradually increasing the distractors.

You're joking! My Learner cannot see.

In that case why not try it with five distinct sounds (or a tactile approach using BIGmacks as outlined above)? One of the sounds you have linked to the BEST.

You're joking! That's way too advanced. My Learner will simply ignore the cards altogether.

Of course it is! That is why you have to begin with the single BEST card and teach the Learner it's meaning. Once you believe that the Learner has a grasp of the concept then you can add a second card into the mix and see if the Learner can select the one that represents the BEST. Selection of the other card should always lead to the withdrawal of the possibility of obtaining BEST for a specified time period.

You're joking! My Learner cannot associate a card with a BEST. She'll just sit and rock.

You may be correct but what are you doing in place of this? How do you know if you do not try? Each time you give the Learner the BEST for a whole term ensure that the card is presented just before. You could make the card shape tactile by drawing around the shape with a glue gun to raise its borders and then filling the shape with a sensory surface such as sand and glue and, when set, painting it the appropriate colour. After a whole term you could try to ascertain if the Learner goes for that particular card when mixed in with a couple of plain cards. If that works then ad a small dot to one of the plain cards and see if the Learner can still do it. Gradually increasing the distractors.

You're joking! My Learner cannot see.

In that case why not try it with five distinct sounds (or a tactile approach using BIGmacks as outlined above)? One of the sounds you have linked to the BEST.

|

Not all our pupils have favourites.

Please do not say that! Yes, they do. It is just that with some individuals the BEST may be very hard to discover. I remember a school that told me they had thought a particular Learner was not motivated by anything until one day a group of musicians came to the school. This young man was sat near to the tuba player and every time he played, the young man's face lit up. It was a certain frequency of sounds that proved to be motivating. Talk to Significant Others first - they are likely to know things that may be motivating or, at least, suggest a possible avenue of investigation. I am always concerned when a Learner is self harming as a form of stimulation. Trying to discover something that is more motivating than poking your own eyes or slapping your own face or biting yourself (and other such behaviours) is difficult. I once worked with a young lady who would regularly poked herself in her eyes as a form of self stimulation. I found that a really strong fan placed close to her face was the only thing that appeared to be at least as motivating. Providing her with safe control of the fan through a single switch proved very successful and was a platform for further development. |

What if a Learner's BEST is not age appropriate?

So what if it isn't? If it is a favourite, it is a place to start and an entry into their world. It is not that everything in the school day will be age inappropriate or that you will be treating the Learners in an age inappropriate way - it is possible to use age inappropriate items in an age appropriate manner. Furthermore, the goal is not to remain with this item, the goal is to use the item as a springboard for moving forward. For me, providing it's ethical and it's a platform for development then it's an acceptable tool. However, when the inspectors are around - I wouldn't recommend the use of age inappropriate things; they tend not to like them!

My Learner has no reaction to card presentation whatsoever even when paired with his BEST.

Try making the card more tactile. Use a glue gun to outline the shape and then infill it with some appropriate sensory surface. Present the card and assist the Learner to explore it before providing the BEST. Always provide the minimum amount of a BEST that will be still motivating to the Learner. Do this for an entire term! Try repeating the technique in the following term.

The staff are getting around the blind presentation by allowing the Learner to make multiple guesses until she gets it 'correct' and then rewarding this response. Is this wrong?

Yes! It may be OK for a short time in a teaching phase to help the Learner to see that only one specific card gets a reward but that should

be a planned period of time. After this period, the staff must treat the selection of one of the other cards as a request (communicative act by the Learner) to stop the activity for (at least) five minutes and do something else instead.

My Learner's BEST is horse riding and we cannot provide that at any time.

In that instance, there are at least two things that you can do instead: select a second favourite (a second BEST) or see if access to a short video of the Learner horse riding will act as a substitute.

The Learner gets it correct about 50% of the time but can have 'off periods'. What is the procedure in this eventuality?

The procedure is always consistent: if the Learner selects an incorrect card staff should treat it as though the Learner had said, "I'm fed up with this, let's stop for five minutes and do something else instead." If the Learner has had a seizure earlier or is known to be 'off' for whatever reason then perhaps you should not undertake the procedure especially if it is likely that all choices at this time will not be correct. However, if you go ahead. an incorrect choice must always result in the termination of the procedure for a set period of time.

The Learner's BEST is chocolate. We can't keep feeding him chocolate all morning!

You need to review the Limiting Rules on the Fundamentals Page of this website. First, you need to establish what is the smallest amount of BEST that you can provide and yet still be motivating. Thus, it need not be a whole bar of chocolate as a reward but rather one square. Indeed, would a half of a square still suffice? What about a quarter? What about a quarter of a chocolate button? Also, once you have done this four times perhaps it's time to stop and do something else instead. If the Learner has managed to get it correct four times then 'whoopee', what a success! Party time! Furthermore, that would equate to one whole chocolate button! That's not going to make him sick or ruin his appetite. Of course, if he chooses incorrectly, the process is terminated for a period of time and no reward is given. As such, it may take a whole session to get even a fraction of a chocolate button!

Stepping Up

So the Learner succeeds at one of the above techniques after quite a long period of time. What does that prove? What then? Well, it shows that the Learning is capable of recalling - remembering a previous event and applying that knowledge to obtain another reward. Isn't that history? Maybe at a very basic level but isn't that where we are at? What then? Ah! Now we leave an increasing time period between presentations of the technique: first we may do it twice or more a day but then we limit it to once a day. Is the Learner still successful? OK. Now we present every two days, then three days, then once a week, once a month ... what does this tell us if the Learner is successful on each presentation? Suppose we left it an entire year and then we did it again with the Learner and s/he still got it right?!! Unlikely I know but not impossible. What we are assessing is the extent of a Learner's memory for a particular POLE.

You're crazy! My Learner will never manage any of this idea.

OK, I am crazy! If you do not believe that this has the slightest chance of succeeding no matter how it is modified for your circumstances

then what about trying one of the other ideas on this page? Surely one of then has some merit for your Learner?

So what if it isn't? If it is a favourite, it is a place to start and an entry into their world. It is not that everything in the school day will be age inappropriate or that you will be treating the Learners in an age inappropriate way - it is possible to use age inappropriate items in an age appropriate manner. Furthermore, the goal is not to remain with this item, the goal is to use the item as a springboard for moving forward. For me, providing it's ethical and it's a platform for development then it's an acceptable tool. However, when the inspectors are around - I wouldn't recommend the use of age inappropriate things; they tend not to like them!

My Learner has no reaction to card presentation whatsoever even when paired with his BEST.

Try making the card more tactile. Use a glue gun to outline the shape and then infill it with some appropriate sensory surface. Present the card and assist the Learner to explore it before providing the BEST. Always provide the minimum amount of a BEST that will be still motivating to the Learner. Do this for an entire term! Try repeating the technique in the following term.

The staff are getting around the blind presentation by allowing the Learner to make multiple guesses until she gets it 'correct' and then rewarding this response. Is this wrong?

Yes! It may be OK for a short time in a teaching phase to help the Learner to see that only one specific card gets a reward but that should

be a planned period of time. After this period, the staff must treat the selection of one of the other cards as a request (communicative act by the Learner) to stop the activity for (at least) five minutes and do something else instead.

My Learner's BEST is horse riding and we cannot provide that at any time.

In that instance, there are at least two things that you can do instead: select a second favourite (a second BEST) or see if access to a short video of the Learner horse riding will act as a substitute.

The Learner gets it correct about 50% of the time but can have 'off periods'. What is the procedure in this eventuality?

The procedure is always consistent: if the Learner selects an incorrect card staff should treat it as though the Learner had said, "I'm fed up with this, let's stop for five minutes and do something else instead." If the Learner has had a seizure earlier or is known to be 'off' for whatever reason then perhaps you should not undertake the procedure especially if it is likely that all choices at this time will not be correct. However, if you go ahead. an incorrect choice must always result in the termination of the procedure for a set period of time.

The Learner's BEST is chocolate. We can't keep feeding him chocolate all morning!

You need to review the Limiting Rules on the Fundamentals Page of this website. First, you need to establish what is the smallest amount of BEST that you can provide and yet still be motivating. Thus, it need not be a whole bar of chocolate as a reward but rather one square. Indeed, would a half of a square still suffice? What about a quarter? What about a quarter of a chocolate button? Also, once you have done this four times perhaps it's time to stop and do something else instead. If the Learner has managed to get it correct four times then 'whoopee', what a success! Party time! Furthermore, that would equate to one whole chocolate button! That's not going to make him sick or ruin his appetite. Of course, if he chooses incorrectly, the process is terminated for a period of time and no reward is given. As such, it may take a whole session to get even a fraction of a chocolate button!

Stepping Up

So the Learner succeeds at one of the above techniques after quite a long period of time. What does that prove? What then? Well, it shows that the Learning is capable of recalling - remembering a previous event and applying that knowledge to obtain another reward. Isn't that history? Maybe at a very basic level but isn't that where we are at? What then? Ah! Now we leave an increasing time period between presentations of the technique: first we may do it twice or more a day but then we limit it to once a day. Is the Learner still successful? OK. Now we present every two days, then three days, then once a week, once a month ... what does this tell us if the Learner is successful on each presentation? Suppose we left it an entire year and then we did it again with the Learner and s/he still got it right?!! Unlikely I know but not impossible. What we are assessing is the extent of a Learner's memory for a particular POLE.

You're crazy! My Learner will never manage any of this idea.

OK, I am crazy! If you do not believe that this has the slightest chance of succeeding no matter how it is modified for your circumstances

then what about trying one of the other ideas on this page? Surely one of then has some merit for your Learner?

Idea Five: Historical Awareness the PowerPoint Way

PowerPoint from Microsoft is a great piece of software but more than that it is an exciting tool for use in the education of those experiencing PMLD. PowerPoint:

1. is available! Most establishments already have it and therefore it does not have to be

purchased for use in the classroom.

2. is accessible. It can be accessed through a touch screen or can easily be driven by a

single switch. S/he cannot use a switch? Yes s/he can! You just need a different sort of

switch!

3. is age appropriate. Materials for use withing PowerPoint can be created quickly and are

within the scope of every staff member. Materials can be tailored to the needs of an

individual.

4. is tireless! It will never give up on a Learner, it will go on and on.

5. is consistent. It always does things the same way every time.

6. is versatile! PowerPoint can incorporate sound effects,music, songs, videos, photographs,

pictures, symbols, animated graphics and more which are easily accessible by Learners.

S/he has a visual impairment? No problem, focus on the use of sounds. S/he is deaf/blind? Ah! Now that may be a bit of a problem for

PowerPoint!

7. will work at the speed of the Learner. If the Learner likes things fast then PowerPoint will go fast. If the Learner likes things slow then

PowerPoint will take its time.

8. can free staff to get on with other things.

9. can be used in a vast number of ways to support learning for Individuals experiencing PMLD. You may be surprised just how useful

this software really is.

10. can speak to the Learner - to provide encouragement, to give instructions, to reward excellent work ...

11. can be used to produce individualized computer based programs which research (See Mechling 2006) has shown results in

consistently greater cognitive engagement when compared to working with a single switch to operate toys or commercial cause and

effect software.

12. can be used to assess awareness of history!

So you are not confident in using PowerPoint in the special needs environment? No problem! Book a Talksense training course and learn how to use PowerPoint to support learning difficulties. Contact Talksense using the form at the bottom of this page for further details.

Let's take a look at one idea for using PowerPoint to establish historical awareness in an individual experiencing PMLD.

So how can PowerPoint help to establish whether or not an Individual Experiencing PMLD (IEPMLD) has an historical awareness? We need to look at the research that has been undertaken with very young babies (and, no I am not suggesting that IEPMLD are akin to babies!). As babies cannot report back to the research scientists, how do they know whether the babies are aware of particular stimuli? It comes down to:

1. is available! Most establishments already have it and therefore it does not have to be

purchased for use in the classroom.

2. is accessible. It can be accessed through a touch screen or can easily be driven by a

single switch. S/he cannot use a switch? Yes s/he can! You just need a different sort of

switch!

3. is age appropriate. Materials for use withing PowerPoint can be created quickly and are

within the scope of every staff member. Materials can be tailored to the needs of an

individual.

4. is tireless! It will never give up on a Learner, it will go on and on.

5. is consistent. It always does things the same way every time.

6. is versatile! PowerPoint can incorporate sound effects,music, songs, videos, photographs,

pictures, symbols, animated graphics and more which are easily accessible by Learners.

S/he has a visual impairment? No problem, focus on the use of sounds. S/he is deaf/blind? Ah! Now that may be a bit of a problem for

PowerPoint!

7. will work at the speed of the Learner. If the Learner likes things fast then PowerPoint will go fast. If the Learner likes things slow then

PowerPoint will take its time.

8. can free staff to get on with other things.

9. can be used in a vast number of ways to support learning for Individuals experiencing PMLD. You may be surprised just how useful

this software really is.

10. can speak to the Learner - to provide encouragement, to give instructions, to reward excellent work ...

11. can be used to produce individualized computer based programs which research (See Mechling 2006) has shown results in

consistently greater cognitive engagement when compared to working with a single switch to operate toys or commercial cause and

effect software.

12. can be used to assess awareness of history!

So you are not confident in using PowerPoint in the special needs environment? No problem! Book a Talksense training course and learn how to use PowerPoint to support learning difficulties. Contact Talksense using the form at the bottom of this page for further details.

Let's take a look at one idea for using PowerPoint to establish historical awareness in an individual experiencing PMLD.

So how can PowerPoint help to establish whether or not an Individual Experiencing PMLD (IEPMLD) has an historical awareness? We need to look at the research that has been undertaken with very young babies (and, no I am not suggesting that IEPMLD are akin to babies!). As babies cannot report back to the research scientists, how do they know whether the babies are aware of particular stimuli? It comes down to:

- preference and choice (the babies repeatedly make choices for specific items); also here

- attention (The babies attend to one stimulus more than another):

|

"I have spent my career trying to figure out what’s going on in

the minds of pre-linguistic infants. And it’s a fascinating puzzle. We can’t peer directly into the mind. What we need is evidence that we can use to make inferences about what’s happening in the mind. Infants don’t speak and they’re also limited in the kinds of coordinated behaviors they can perform. But they’re quite good at controlling what they look at and how long they look at things. So a number of researchers over the years, including me, have developed ways to use visual attention as a measure of what babies understand in a situation." Amanda Woodward (2013) Also Here and Here and Here |

- suction (the babies suck on a pacifier more when they see, for example, familiar faces)

Assuming, we are not going to condone sucking on pacifiers in the classroom, we still have the options of preference and attention as indicators of cognition. With PowerPoint we can assess attention by observation of how interested and for how long a Learner works with a particular screen before moving on. If a Learner repeatedly spends more time focusing on one screen from a set of screens within a PowerPoint presentation it is unlikely to be by chance alone;, something on or about the screen must be recognised or of interest.

Powerpoint can display a photographic image as a slide in a presentation. Thus, we can quickly create a presentation of perhaps six slides of people one of which is an earlier photograph of the Learner or a member of the Learners family. All the others are similar photographs but completely unknown to the Learner. The PowerPoint program is set so that the final slide cycles back to the beginning to form an endless cycle and the slides are controlled by a single switch attached to the computer through an interface such as Sensory Software's 'Joy Cable' which plugs into any available USB socket and allows an attached switch to act as any key or mouse activation through an accompanying piece of software. Each time the switch is activated, PowerPoint will move to the next slide. If the Learner in question is not going to explore the switch (and thus activate it repeatedly), it may be that, initially, we permit accidental Learner movements to activate the Joycable system. This might be achieved by using AbleNet's string switch attached to a wrist band by means of a strong elastic band such when the Learner moves his/her arm (or a leg) in any direction the switch is activated. Thus, each time the Learner moves a particular body part, the slide on the PowerPoint changes. It may take some considerable time for an IEPMLD to connect body movement to the change but perhaps ten minutes each day can be given over to this activity. Each slide could have a recognisable voice calling out the Learner's name every five to ten seconds to focus the Learner's attention on the images.

After a few weeks of work staff notice that the Learner is consistently moving through the slides more rapidly than was the case at the beginning. Furthermore, they notice that the Learner is spending more time on one particular slide than the others and it happens to be the picture of the Learner with mother as a child. What does this tell us? It suggests at least two things: The Learner -

- is making a connection between movement of a body part and the control of the screen;

- is more interested in the picture of him/herself and mother and therefore has some recognition of a past time.

You are crazy! That's far too advanced for my Learners

OK, Perhaps we can have a different starting point. As we know that individualised computer program produce more cognitive engagement than off the shelf software ((See Mechling 2006) perhaps we can start with six slides ALL of interest to the Learner coupled with familiar family voices and favourite music etc such that any activation of the switch moves PowerPoint to another interesting slide. We do this until we have some evidence that the Learner is making the connection between body movement and slide progression and, yes, I realise this may take some considerable time. Only then do we move to phase two and have one slide of the set of six which is interesting because of some historical event which we hope the Learner will recognise. Would that be a better approach?

Your joking. My Learner will never make a connection between movement and slide progression.

How do you know? Have you tried this?

That may be fine for some Learners but mine does not move his arm or his leg.

OK. There is an AbleNet switch known as a SCATIR switch which can work from an eyeblink or a facial twitch. Somewhere there is a switch which is compatible with your Learner which will allow accidental activation.

Suppose the Learner repeatedly spends more time on another slide and not on his picture?

S/he must be doing that for a reason. If you can discover that reason you may have a tool to promote further progress.

I have a young lady who rocks back and forth but does not appear to attend and certainly does not make a choice. I am not convinced that what you are suggesting will work for her.

Perhaps we can turn the rocking into a means of switch activation. There are at least two methods for doing this: push and pull. In the 'push methodology' the Learner activates the switch by rocking into it. Thus we need to use a suitable switch and mount the switch such that it is in the line of the rocking motion. I would suggest a wobble switch from Ability-World mounted on a Sensitrac slider and Magic Arm using Ultramate Velcro (its incredibly strong) form the same company. Now some Learners with whom I have previously tried this technique have simply adapted their rocking motion such that they do not rock into the switch. However, I am pleased when this happens! Why? Because it shows awareness of the switch and I know that if they are aware there is cognition with which I can work. If the Learner rocks into the switch, it will be activated from time to time. If we can provide the BEST POLE for that Learner on switch activation then we might have a means of moving forward. The 'pull methodology' requires a safety pin and a length of cotton. The safety pin is attached to the Learner's jumper or other item of clothing and the cotton is threaded through the safety pin. The other end of the cotton is attached to a firmly mounted switch such that when the Learner rocks forward sufficiently the switch is activated. Either a string switch or a wobble switch might be used here. If the Learner gets up and walks away (if the Learner is ambulant) then the cotton will snap and no danger or damage ensues. There are of course other options:

- Proximity switch: if the Learner rocks close to it the switch is activated.

- Placing a cushion or pillow switch at the back of the Learner such that the reverse of the rock activates the switch

- Tilt switch: A tilt switch activates when it is in a certain orientation and therefore it may be possible to attach to a Learner who rocks such that it will activate at specific times only.

- Sound Operated Switch - which, as its name implies, operates by sound only. Does the Learner make occasional sounds or can we attach something to them so that they make occasional sounds?

- Other? There will be other possibilities too!

What we need to do is to turn part of the rocking motion into a means of switch activation and then make the switch activate something which the Learner will find motivating. If you do not yet know what a particular Learner's BEST is then talk to Significant Others and see if they can suggest anything to trial. It may be a case of trial and error for a very few Learners.

Talksense offers a complete day's training for staff on the use of PowerPoint for Learning difficulties. You will be amazed at just what is possible with a bit of imagination and a little know how. If you would like to know more use the contact form at the bottom of this page.

Idea Six: Establish Cause and Effect

"These results suggest that from a mental age level of 2 months children are equipped to detect cause and effect relationships and build up a picture of their world based on expectancies about such relationships; and that violations of these expectancies can lead to negative effects." O'Brien, Y., Glenn, S., & Cunningham, C. (1994)