Sensory Stories: Theory and Practice

"the existence of learning difficulties so extreme as to present a major obstacle to participation in some of the most basic experiences in life, ought rather to generate educational aims concerned with enabling them to participate in those experiences. An aim which we might express as: 'enabling the child to participate in those experiences which are uniquely human'." (Ware, 1994, page 71)

"It should also become evident that people that may seem to be 'cognitively limited' nevertheless have a great deal of cognitive competence. You will see that without this competence simple things like pointing or eye gaze in a way that is appropriate to the context would not be possible. Such seemingly simple behaviours are still beyond the capabilities of very sophisticated computer simulations and could not occur without considerable knowledge of the world and how to solve problems in that world. (Anderson J. 1990). Hopefully, you will see that even 'cognitively limited' individuals are capable of more than most people think they are (Bray N. & Turner L. 1986, 1987). Facilitators can build on this cognitive base." (Bray N. 1990)

This page concerns both the theory and practice of Sensory Stories for groups of Learners experiencing PMLD within any establishment (School, College, Centre ...). While the page addresses the issue of utilising the Sensory Story approach with groups, it does not preclude its use with an individual Learner although some of the techniques may require adjustment.

TalkSense is grateful to, and would like to acknowledge the significant contribution of, Melanie Bullivant of Chadsgrove School in Worcestershire to this webpage. Melanie is a special education teacher currently studying for her Master of Education Degree at Birmingham University ... Melanie has been invaluable in not only adding to the academic structure of this page but also in helping to keep the recommended practice grounded in real life and real time provision in the Special Education classroom.

The structure of this page may change from time to time. It will evolve and new things will undoubtedly be added. In order that those wishing to use this page might be made aware if something has altered since their last visit, a page update stamp will detail the last date on which the page was amended or altered in any significant way:

This page was last updated on 8th November 2016

Is it possible for an Individual who is Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties (IEPMLD) to be literate? Does the answer to the question depend on how we define literacy? In one sense, yes but the definition of a word cannot simply be twisted to suit a particular need. Almost by definition, an Individual Experiencing PMLD is not literate and should that person ever acquire literacy skills, they could no longer be so classified. The Question then becomes, 'Can IEPMLD experience literacy?' Again, this depends on how broad we will permit the brushstroke defining 'literacy' to be. However, on a conventional definition of the term, the answer would almost certainly be 'no'. What may be presently possible is for this group of people to have some level of inclusive access to 'special' presentations of stories. While any person might be integrated into (placed within) a group in a room listening to a story told by another, it cannot be claimed such a person at that time is included:

"These pupils will need books interpreted for them if they are to learn from them. Their profound intellectual impairment is likely to prevent them from understanding the words, even if they are read to them, while their likely additional impairments will lead to access difficulties, such as seeing the book or hearing the words read. In summary, this group is likely to have a complex profile of needs which result in

significant barriers to acquiring literacy skills." (Fletcher-Campbell, DfEE, 2000).

Is it then possible to 'present' a story to an Individual Experiencing PMLD (or a small group) in such a way that it becomes inclusive such that each member has an opportunity to take something meaningful from the experience? The objective of this webpage is to explore that premise.

"When Keith Park and I embarked on Odyssey Now, we met with considerable skepticism, and sometimes wondered if we were on the right track." (Grove 1998 page 85)

"Conventional literacy is clearly not open to children (or adults) with profound learning disabilities as they are not going to learn to read and write. However, if we conceive of literacy as ‘inclusive’, there may be ways in which even the most profoundly disabled can take part." (Lacey 2006, page 12)

"It should also become evident that people that may seem to be 'cognitively limited' nevertheless have a great deal of cognitive competence. You will see that without this competence simple things like pointing or eye gaze in a way that is appropriate to the context would not be possible. Such seemingly simple behaviours are still beyond the capabilities of very sophisticated computer simulations and could not occur without considerable knowledge of the world and how to solve problems in that world. (Anderson J. 1990). Hopefully, you will see that even 'cognitively limited' individuals are capable of more than most people think they are (Bray N. & Turner L. 1986, 1987). Facilitators can build on this cognitive base." (Bray N. 1990)

This page concerns both the theory and practice of Sensory Stories for groups of Learners experiencing PMLD within any establishment (School, College, Centre ...). While the page addresses the issue of utilising the Sensory Story approach with groups, it does not preclude its use with an individual Learner although some of the techniques may require adjustment.

TalkSense is grateful to, and would like to acknowledge the significant contribution of, Melanie Bullivant of Chadsgrove School in Worcestershire to this webpage. Melanie is a special education teacher currently studying for her Master of Education Degree at Birmingham University ... Melanie has been invaluable in not only adding to the academic structure of this page but also in helping to keep the recommended practice grounded in real life and real time provision in the Special Education classroom.

The structure of this page may change from time to time. It will evolve and new things will undoubtedly be added. In order that those wishing to use this page might be made aware if something has altered since their last visit, a page update stamp will detail the last date on which the page was amended or altered in any significant way:

This page was last updated on 8th November 2016

Is it possible for an Individual who is Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties (IEPMLD) to be literate? Does the answer to the question depend on how we define literacy? In one sense, yes but the definition of a word cannot simply be twisted to suit a particular need. Almost by definition, an Individual Experiencing PMLD is not literate and should that person ever acquire literacy skills, they could no longer be so classified. The Question then becomes, 'Can IEPMLD experience literacy?' Again, this depends on how broad we will permit the brushstroke defining 'literacy' to be. However, on a conventional definition of the term, the answer would almost certainly be 'no'. What may be presently possible is for this group of people to have some level of inclusive access to 'special' presentations of stories. While any person might be integrated into (placed within) a group in a room listening to a story told by another, it cannot be claimed such a person at that time is included:

- some will be unable to hear;

- some may not speak the language of the story;

- some may speak the language but not comprehend the complexity of the semantics and or the syntax;

- some may find the speed at which the story unfolds too fast;

- some may be distracted by some other stimuli and fail to attend;

- some may be unable to sit through the entire length of the presentation (for whatever reason);

- some may have behaviours that others find challenging;

- some may fall asleep;

- some may be unable to see the actions of the narrator and or the visual props that s/he is using and thus not have the same experience as others.

"These pupils will need books interpreted for them if they are to learn from them. Their profound intellectual impairment is likely to prevent them from understanding the words, even if they are read to them, while their likely additional impairments will lead to access difficulties, such as seeing the book or hearing the words read. In summary, this group is likely to have a complex profile of needs which result in

significant barriers to acquiring literacy skills." (Fletcher-Campbell, DfEE, 2000).

Is it then possible to 'present' a story to an Individual Experiencing PMLD (or a small group) in such a way that it becomes inclusive such that each member has an opportunity to take something meaningful from the experience? The objective of this webpage is to explore that premise.

"When Keith Park and I embarked on Odyssey Now, we met with considerable skepticism, and sometimes wondered if we were on the right track." (Grove 1998 page 85)

"Conventional literacy is clearly not open to children (or adults) with profound learning disabilities as they are not going to learn to read and write. However, if we conceive of literacy as ‘inclusive’, there may be ways in which even the most profoundly disabled can take part." (Lacey 2006, page 12)

What is a Sensory Story? Definition:

"There is a range of ways of sharing stories with people with PMLD. Involving people with PMLD in story telling is usually multi-sensory and is unlikely to focus on a book, although the story may have originally come from a book. The multi-sensory experience of story telling is likely to involve objects to touch, look at and listen to; things to smell and even to taste. Suitable sentences are only usually only a few sentences long with each sentence being repeated several times to help the listeners to become familiar with them and learn to anticipate what is coming next." (Lacey 2012 , page 7)

"Telling a Sensory Stories is unlike sharing a typical story. Told in person they engage, include, fascinate and delight everyone."

www.kickstarter.com/projects/sensorystory/sensory-stories

"Bag Books are aimed at those who cannot benefit from mainstream books. They can be enjoyed without being understood as they are told interactively through voice and emotion rather than words and pictures. They are designed for people with profound and multiple learning disabilities (a maximum developmental age of 18 months), people with severe learning disabilities (a maximum developmental age of 6 years) or people with severe autistic spectrum disorders. They are also hugely beneficial to those with visual and hearing impairments." www.bagbooks.org

"Sensory Stories are simply sensory experiences sequenced within a narrative that can allow individuals with PMLD to participate in the world and provide a way for them to be ‘heard’."

Joanna Grace

"Multi-Sensory Story Telling (MSST) is a structured method in which caregivers read personalised stories to children with Profound Multiple Disabilities (PMD) to motivate these children to interact and explore their environment (Pamis, 2002; Multiplus, 2008). A story consists of 6 to 8 pages and every page includes 1 or 2 short sentences. Each page is supported by an object of reference, stimulating the different senses, to draw the child’s attention, invite exploration and to support meaning making." (Willems 2014 Page 5)

"Sensory Stories are a method to allow children with sensory modulation issues - sensory integration disorder, sensory integration dysfunction - to cope with everyday experiences."

www.sensorystories.com

"A Sensory Story is a story told using a combination of words and sensory experiences. The words and the experiences are of equal value when conveying the narrative." (Grace 2014 page 13)

"Sensory storytelling – storytelling supported by the use of relevant objects chosen for their sensory qualities and appeal – has been identified as an enjoyable activity for individuals with PMLD"

Preece, D. & Zhao, Y. (2014)

While all of the above quotations hold some aspect of the nature of the Sensory Story within the words utilised, we do not think they totally capture the essence of the subject. We all grew up loving stories. We read them, listened to them, and or watched them on our screens almost every day. Story telling is one thing that has passed down from generation to generation throughout the ages. It is a quintessentially human endeavor. Therefore, involving those who, through no fault of their own, might be denied such pleasure in the process should be a part of any curriculum designed to support special educational needs:

"Sharing stories is an enriching part of life; through stories we learn who we are and who others are, we find our identities and a sense of belonging, be that in a family, a community, within a faith or a cultural group, as well as our place in history and society."

('Storytelling for young people with VI, learning difficulties and additional complex needs', RNIB Pears Centre training materials, 2014)

"It is my passionate conviction that, on the contrary, poetry and stories address the most fundamental needs of any human being, regardless of their level of disability, and that some of the best opportunities for developing the functional communication skills of students arise in these contexts." (Grove 1998)

"I believe that stories and oral story telling are a very effective way of supporting the development of children and adults with PMLD." Dowling 2011, page 28

A Sensory Story is an attempt by a person (or a group of people) to relate a story to a Learner (or group of Learners) in an 'inclusive' manner that will:

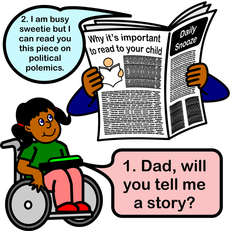

As such, it may be justifiably claimed that all good story telling is 'sensory': when parents read to their children: typically, they put on 'voices' for each character, and point to related aspects of any pictures that might accompany the text. The child may make a request for the parent to repeat a specific line and also ask questions about any point that they haven't quite understood. While all good story-telling has, therefore, some 'sensory' aspect, imagine that the Learner (be s/he a child or an adult) is experiencing a severe or a profound learning difficulty, does not speak, and cannot ask for clarification. Indeed, the Learner may have additional sensory impairments such that s/he cannot see or hear so well. These and other issues will, almost certainly, compound the Learner's ability to make sense of the tale as it unfolds such that it becomes a bewildering set of incomprehensible sensory inputs. While the story teller may believe the Learner is sitting and understanding each aspect, this may be far from the truth especially if the Learner has no way of telling the story teller of the problem. While the Learner who is sitting still is not indicative of comprehension, the Learner who is continually moving may also indicate a lack of focus on the narrative. Individuals Experiencing PMLD may self stimulate (stimming). Stimming typically involves a repeated behaviour which serves some form of personal need and may also serve to create individual social detachment. Such behaviour might occur as a result of a lack of stimulation:

"Self-active engagement consists of stereotyped behaviours that develop to compensate for lack of meaningful sensory stimulation." (Pagliano 2001)

or may also result as an individual's means of reducing sensory overload:

"In response to sensory overload sensations, many students with AS engage in behaviors referred to as "stimming." "Stims" are repetitive behaviors that seem to reduce the anxiety associated with sensory overload and enhance focus and concentration. Examples include spinning or whirling, repetitive finger flicking or fiddling with objects." (Boratynec 2010, page 10)

Whatever the cause, a Learner who is stimming during a Sensory Story session is unlikely to be attending fully to the narrative. Looking at this another way, the lack of such behaviour from a Learner during a Sensory Story session may also be indicative of some interest in some aspect of the narrative at that point in time.

It is our experience that the Sensory Story technique can be found in Special Education around the world from the USA to Taiwan. Sensory stories are also used with all ages and with diverse populations (see for example Aird and Heath, 1999; Pidgeon, 1999; PAMIS 2007; Boer and Wikkerman, 2008), however, there is a great variety in the manner in which it is undertaken with some staff making use of what we might consider to be 'less than best practice'. Thus, on this page, we will not only attempt to define a Sensory Story and distinguish it from other like approaches but also set out a number of guidelines for what we would consider to be best practice. While you may not agree with every point made, we hope that this page both challenges and stimulates your thinking such that you create your own ways in which to improve the practice in your establishment.

We take a 'Sensory Story' to be the means of relating a tale to a group of Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties (IEPMLD) in a manner that is N.I.C.E.:

Normal means that we should be relating stories to which our Learners can relate and have some chance of understanding. Our Learners have no experience of space or hobgoblins or epic Greek sea journeys (or probably just any sea journey) and thus such themes confound the Learners chance of comprehension. Normal in this sense, therefore, means 'everyday': things of which the Learner has some experience and to which s/he are more likely to be able to relate.

"The subject of the story applies to actual experiences from the daily live of a person, often something the listener particularly enjoys. E.g. taking a bath, having a party, going to the beach, or watch the football." (Boer & Wikkerman, 2008. page 2)

"Moreover, the story must be related to daily life activities and/or reflect aspects of the individual’s personality or interests. One of the goals of MSST is to make the Multi Disabled children familiar with certain situations in their daily life to improve coping with sensitive topics. It is found that young children learn more effectively and efficiently when instructions are contextually relevant, developmentally appropriate, and instructions capitalises on the child’s focus and interest." (Willems 2014 Page 6)

Inclusive does NOT mean the same thing as 'integrated' even though it becomes confusing because some researchers treat the terms as equivalent (see for example; Parekh 2013). Simply occupying the same space as other beings does not always mean that you are included. You might attend a lecture at Oxford University. You would be integrated into the group, sat with the others attending that lecture, however the lecture may leave you completely baffled. You were integrated but NOT included. Inclusive also means that the Learners participate in the story and the story is delivered in such a way as to make it more accessible to each member of the group. In the best practice, Learners are enabled to take 'control' of some aspect of the story as it unfolds.

"Inclusive literacy enables everyone, including those at OECD Level 1, to enjoy books, stories and other media in a way that has meaning

for them, even if conventional reading and writing are not achievable." (Lacey, Layton, Miller, Goldbart & Lawson 2007, page 150)

Many teachers working in special education settings may have mixed ability groups comprising one or two Learners Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties together with others at differing levels of ability but all having a special requirement of one form or another. For such diverse groupings good practice in the use of Sensory Stories can involve everyone at their own level of understanding with some playing pivotal roles in the story as it unfolds (the goal is control). In this sense, also, Sensory Stories are inclusive. The Learners can all work together to benefit each other and all gain from the experience each at their own level of understanding.

Interactive means that staff spend time interacting positively with Learner throughout the story. It does not follow that staff have to operate in a regulating manner and that Learner control is lost but, rather, staff take every opportunity to interact with Learners to illuminate and illustrate the concepts involved using identical approaches (as far as is practical - it does not preclude an evolving practice based on Learner development) such that Learners can begin to show anticipation of what is to follow. In this role, staff should be encouraged to give the Learners the lead and to note and report and record any new aspects to Learner behaviour. Interactive also means that the Learner participates; with participation comes the chance of emerging communication:

"Participation is the only prerequisite to communication. Without participation, there is no one to talk to, nothing to talk about, and no reason to communicate." (Beukelman, D. & Mirenda, P., 1992, page 177)

Comprehensible involves both the above concepts of 'Normal' and 'Inclusion'. A comprehensible narrative involves 'cognitive coat-pegs' on which the Learner can attach meaning and make some sense of the story as it unfolds. Comprehensible necessarily means multi-sensory for it is through multi-sensory stimuli that the Learner may begin to comprehend some of what is occurring:

"multi-sensory training engages individuals with different learning styles and disabilities, because the information enters through different channels at the same time, which contributes to the apprehension of the story" (Willems 2014 page 6)

Comprehensible must include some notion of the length of the story: too long a story will make it very hard for those with limited attention spans and information processing difficulties to understand what is happening as a whole:

"Because of the short attention and concentration span, the stories must be short" (Willems 2014 page 6)

Consistent means that each time the story is 'read' it is done in the same manner such that the audience may begin to predict what happens next. Sensory stories are not just utilised once but over and over again. This is no different to story choice by any Learner - given a choice, they will choose the same story over and over because they like the characters and, as they get to know the story, they can predict what happens next and make sense of the text to which their parent is pointing. Achieving consistency in a special education is sometimes difficult as there can be any number of unexpected interruptions to any session. Thus, this area is addressed further in a section below.

"Telling the story always happens in the same way and order, with a lot of intonation and at a low pace." (Boer & Wikkerman, 2008. page 2)

"All stories are told in the same order, using the same words, creating a strong repetitive component. This fixed structure makes the story more understandable and evokes a sense of having control over the environment." (Willems 2014 Page 6)

"For some individuals, having a story shared with them in a consistent manner can help them to develop their understanding, communication and expression of preferences and also relieve them of any anxieties they may feel around sharing the story and so enable them to interact with the stimuli more." (Grace 2014 page 35)

Grace (2014 Chapter Three) defines four 'tips' for consistently relating a Sensory Story; these are:

Enjoyable means that the Learners are having fun and are not falling asleep, sitting rocking or engaging in some other self stimulatory behaviour. Thus, such things as the topic, the mode of story telling, the role of each Learner in the group, and length of the story may all have an impact on it's 'fun factor'.

Enjoyable also includes the team supporting the Learners during the story. Fun for all!

Educational means that we are relating the story for a reason. Isn't having fun sufficient a reason? Sure it is providing that in the rest of the session and in other aspects of the curriculum educational aspects are addressed. However, can't something be both educational and fun?!

Thus, our definition is:

A sensory Story is any set of experiences tailored to the specific needs of an individual (or individuals) that are N.I.C.E. and, when taken as a whole, relay some message, moral, myth, monologue, monograph, or matter. (Bullivant and Jones 2016)

Sensory Stories are NICE stories!

Please Note: Sensory Stories, Social Stories, Sensitive Stories, and Story Sharing are related but different approaches. Story sharing is not covered on this webpage. Social Stories are outlined in the next section but are not covered in any greater depth.

"Telling a Sensory Stories is unlike sharing a typical story. Told in person they engage, include, fascinate and delight everyone."

www.kickstarter.com/projects/sensorystory/sensory-stories

"Bag Books are aimed at those who cannot benefit from mainstream books. They can be enjoyed without being understood as they are told interactively through voice and emotion rather than words and pictures. They are designed for people with profound and multiple learning disabilities (a maximum developmental age of 18 months), people with severe learning disabilities (a maximum developmental age of 6 years) or people with severe autistic spectrum disorders. They are also hugely beneficial to those with visual and hearing impairments." www.bagbooks.org

"Sensory Stories are simply sensory experiences sequenced within a narrative that can allow individuals with PMLD to participate in the world and provide a way for them to be ‘heard’."

Joanna Grace

"Multi-Sensory Story Telling (MSST) is a structured method in which caregivers read personalised stories to children with Profound Multiple Disabilities (PMD) to motivate these children to interact and explore their environment (Pamis, 2002; Multiplus, 2008). A story consists of 6 to 8 pages and every page includes 1 or 2 short sentences. Each page is supported by an object of reference, stimulating the different senses, to draw the child’s attention, invite exploration and to support meaning making." (Willems 2014 Page 5)

"Sensory Stories are a method to allow children with sensory modulation issues - sensory integration disorder, sensory integration dysfunction - to cope with everyday experiences."

www.sensorystories.com

"A Sensory Story is a story told using a combination of words and sensory experiences. The words and the experiences are of equal value when conveying the narrative." (Grace 2014 page 13)

"Sensory storytelling – storytelling supported by the use of relevant objects chosen for their sensory qualities and appeal – has been identified as an enjoyable activity for individuals with PMLD"

Preece, D. & Zhao, Y. (2014)

While all of the above quotations hold some aspect of the nature of the Sensory Story within the words utilised, we do not think they totally capture the essence of the subject. We all grew up loving stories. We read them, listened to them, and or watched them on our screens almost every day. Story telling is one thing that has passed down from generation to generation throughout the ages. It is a quintessentially human endeavor. Therefore, involving those who, through no fault of their own, might be denied such pleasure in the process should be a part of any curriculum designed to support special educational needs:

"Sharing stories is an enriching part of life; through stories we learn who we are and who others are, we find our identities and a sense of belonging, be that in a family, a community, within a faith or a cultural group, as well as our place in history and society."

('Storytelling for young people with VI, learning difficulties and additional complex needs', RNIB Pears Centre training materials, 2014)

"It is my passionate conviction that, on the contrary, poetry and stories address the most fundamental needs of any human being, regardless of their level of disability, and that some of the best opportunities for developing the functional communication skills of students arise in these contexts." (Grove 1998)

"I believe that stories and oral story telling are a very effective way of supporting the development of children and adults with PMLD." Dowling 2011, page 28

A Sensory Story is an attempt by a person (or a group of people) to relate a story to a Learner (or group of Learners) in an 'inclusive' manner that will:

- bring the story to life;

- better enable the Learners to play an active role;

- be enjoyable for each Learner;

- enable enhanced Learner comprehension of each aspect of the tale as it unfolds;

- provide sensory experiences that relate directly to the narrative;

- provide sensory experiences that relate directly to the individual;

- help develop the Learner's understanding of his or her world.

As such, it may be justifiably claimed that all good story telling is 'sensory': when parents read to their children: typically, they put on 'voices' for each character, and point to related aspects of any pictures that might accompany the text. The child may make a request for the parent to repeat a specific line and also ask questions about any point that they haven't quite understood. While all good story-telling has, therefore, some 'sensory' aspect, imagine that the Learner (be s/he a child or an adult) is experiencing a severe or a profound learning difficulty, does not speak, and cannot ask for clarification. Indeed, the Learner may have additional sensory impairments such that s/he cannot see or hear so well. These and other issues will, almost certainly, compound the Learner's ability to make sense of the tale as it unfolds such that it becomes a bewildering set of incomprehensible sensory inputs. While the story teller may believe the Learner is sitting and understanding each aspect, this may be far from the truth especially if the Learner has no way of telling the story teller of the problem. While the Learner who is sitting still is not indicative of comprehension, the Learner who is continually moving may also indicate a lack of focus on the narrative. Individuals Experiencing PMLD may self stimulate (stimming). Stimming typically involves a repeated behaviour which serves some form of personal need and may also serve to create individual social detachment. Such behaviour might occur as a result of a lack of stimulation:

"Self-active engagement consists of stereotyped behaviours that develop to compensate for lack of meaningful sensory stimulation." (Pagliano 2001)

or may also result as an individual's means of reducing sensory overload:

"In response to sensory overload sensations, many students with AS engage in behaviors referred to as "stimming." "Stims" are repetitive behaviors that seem to reduce the anxiety associated with sensory overload and enhance focus and concentration. Examples include spinning or whirling, repetitive finger flicking or fiddling with objects." (Boratynec 2010, page 10)

Whatever the cause, a Learner who is stimming during a Sensory Story session is unlikely to be attending fully to the narrative. Looking at this another way, the lack of such behaviour from a Learner during a Sensory Story session may also be indicative of some interest in some aspect of the narrative at that point in time.

It is our experience that the Sensory Story technique can be found in Special Education around the world from the USA to Taiwan. Sensory stories are also used with all ages and with diverse populations (see for example Aird and Heath, 1999; Pidgeon, 1999; PAMIS 2007; Boer and Wikkerman, 2008), however, there is a great variety in the manner in which it is undertaken with some staff making use of what we might consider to be 'less than best practice'. Thus, on this page, we will not only attempt to define a Sensory Story and distinguish it from other like approaches but also set out a number of guidelines for what we would consider to be best practice. While you may not agree with every point made, we hope that this page both challenges and stimulates your thinking such that you create your own ways in which to improve the practice in your establishment.

We take a 'Sensory Story' to be the means of relating a tale to a group of Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties (IEPMLD) in a manner that is N.I.C.E.:

- Normal;

- Inclusive and Interactive;

- Comprehensible and Consistent

- Enjoyable and Educational.

Normal means that we should be relating stories to which our Learners can relate and have some chance of understanding. Our Learners have no experience of space or hobgoblins or epic Greek sea journeys (or probably just any sea journey) and thus such themes confound the Learners chance of comprehension. Normal in this sense, therefore, means 'everyday': things of which the Learner has some experience and to which s/he are more likely to be able to relate.

"The subject of the story applies to actual experiences from the daily live of a person, often something the listener particularly enjoys. E.g. taking a bath, having a party, going to the beach, or watch the football." (Boer & Wikkerman, 2008. page 2)

"Moreover, the story must be related to daily life activities and/or reflect aspects of the individual’s personality or interests. One of the goals of MSST is to make the Multi Disabled children familiar with certain situations in their daily life to improve coping with sensitive topics. It is found that young children learn more effectively and efficiently when instructions are contextually relevant, developmentally appropriate, and instructions capitalises on the child’s focus and interest." (Willems 2014 Page 6)

Inclusive does NOT mean the same thing as 'integrated' even though it becomes confusing because some researchers treat the terms as equivalent (see for example; Parekh 2013). Simply occupying the same space as other beings does not always mean that you are included. You might attend a lecture at Oxford University. You would be integrated into the group, sat with the others attending that lecture, however the lecture may leave you completely baffled. You were integrated but NOT included. Inclusive also means that the Learners participate in the story and the story is delivered in such a way as to make it more accessible to each member of the group. In the best practice, Learners are enabled to take 'control' of some aspect of the story as it unfolds.

"Inclusive literacy enables everyone, including those at OECD Level 1, to enjoy books, stories and other media in a way that has meaning

for them, even if conventional reading and writing are not achievable." (Lacey, Layton, Miller, Goldbart & Lawson 2007, page 150)

Many teachers working in special education settings may have mixed ability groups comprising one or two Learners Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties together with others at differing levels of ability but all having a special requirement of one form or another. For such diverse groupings good practice in the use of Sensory Stories can involve everyone at their own level of understanding with some playing pivotal roles in the story as it unfolds (the goal is control). In this sense, also, Sensory Stories are inclusive. The Learners can all work together to benefit each other and all gain from the experience each at their own level of understanding.

Interactive means that staff spend time interacting positively with Learner throughout the story. It does not follow that staff have to operate in a regulating manner and that Learner control is lost but, rather, staff take every opportunity to interact with Learners to illuminate and illustrate the concepts involved using identical approaches (as far as is practical - it does not preclude an evolving practice based on Learner development) such that Learners can begin to show anticipation of what is to follow. In this role, staff should be encouraged to give the Learners the lead and to note and report and record any new aspects to Learner behaviour. Interactive also means that the Learner participates; with participation comes the chance of emerging communication:

"Participation is the only prerequisite to communication. Without participation, there is no one to talk to, nothing to talk about, and no reason to communicate." (Beukelman, D. & Mirenda, P., 1992, page 177)

Comprehensible involves both the above concepts of 'Normal' and 'Inclusion'. A comprehensible narrative involves 'cognitive coat-pegs' on which the Learner can attach meaning and make some sense of the story as it unfolds. Comprehensible necessarily means multi-sensory for it is through multi-sensory stimuli that the Learner may begin to comprehend some of what is occurring:

"multi-sensory training engages individuals with different learning styles and disabilities, because the information enters through different channels at the same time, which contributes to the apprehension of the story" (Willems 2014 page 6)

Comprehensible must include some notion of the length of the story: too long a story will make it very hard for those with limited attention spans and information processing difficulties to understand what is happening as a whole:

"Because of the short attention and concentration span, the stories must be short" (Willems 2014 page 6)

Consistent means that each time the story is 'read' it is done in the same manner such that the audience may begin to predict what happens next. Sensory stories are not just utilised once but over and over again. This is no different to story choice by any Learner - given a choice, they will choose the same story over and over because they like the characters and, as they get to know the story, they can predict what happens next and make sense of the text to which their parent is pointing. Achieving consistency in a special education is sometimes difficult as there can be any number of unexpected interruptions to any session. Thus, this area is addressed further in a section below.

"Telling the story always happens in the same way and order, with a lot of intonation and at a low pace." (Boer & Wikkerman, 2008. page 2)

"All stories are told in the same order, using the same words, creating a strong repetitive component. This fixed structure makes the story more understandable and evokes a sense of having control over the environment." (Willems 2014 Page 6)

"For some individuals, having a story shared with them in a consistent manner can help them to develop their understanding, communication and expression of preferences and also relieve them of any anxieties they may feel around sharing the story and so enable them to interact with the stimuli more." (Grace 2014 page 35)

Grace (2014 Chapter Three) defines four 'tips' for consistently relating a Sensory Story; these are:

- Preparation - have everything that you need checked and ready; knowing what you are going to do to illustrate the story line;

- Rate of relating - take your time and allow the Learner(s) the time to process the information being presented;

- Sticking to the story line - in order for a Learner to anticipate what happens next it must be the same every time;

- Understanding your audience - deliver in a manner that provides the best opportunity for learning for particular Individuals

Enjoyable means that the Learners are having fun and are not falling asleep, sitting rocking or engaging in some other self stimulatory behaviour. Thus, such things as the topic, the mode of story telling, the role of each Learner in the group, and length of the story may all have an impact on it's 'fun factor'.

Enjoyable also includes the team supporting the Learners during the story. Fun for all!

Educational means that we are relating the story for a reason. Isn't having fun sufficient a reason? Sure it is providing that in the rest of the session and in other aspects of the curriculum educational aspects are addressed. However, can't something be both educational and fun?!

Thus, our definition is:

A sensory Story is any set of experiences tailored to the specific needs of an individual (or individuals) that are N.I.C.E. and, when taken as a whole, relay some message, moral, myth, monologue, monograph, or matter. (Bullivant and Jones 2016)

Sensory Stories are NICE stories!

Please Note: Sensory Stories, Social Stories, Sensitive Stories, and Story Sharing are related but different approaches. Story sharing is not covered on this webpage. Social Stories are outlined in the next section but are not covered in any greater depth.

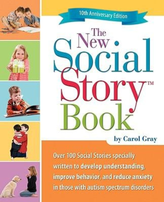

Sensory Stories and Social Stories

Sensory Stories and Social Stories are often confused. While a Sensory Story might also be a Social Story and while a Social Story might also be a Sensory Story, the two are not the same. A Sensory Story does not have to be a Social Story nor a Social Story a Sensory one. Even researchers sometimes get confused and use the term Sensory Story when they really mean Social Story as do many in the Bibliography section of this webpage (See for example: Sherick 2004). If researchers use the terms interchangeably it is no wonder that people get confused!

So what is the difference between a Sensory Story and Social Story? As we have already defined the nature of a Sensory Story (in the above section on this webpage), we will concentrate on providing an explanation of Social Stories such that the distinction between the two might be made explicit.

Carol Gray, former consultant to students with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), first defined Social Stories™ in 1991. Gray defines a social story as describing:

"a situation, skill, or concept in terms of relevant social cues, perspectives, and common responses in a specifically defined style and format. The goal of a Social Story is to share accurate social information in a patient and reassuring manner that is easily understood by its audience. Half of all Social Stories developed should affirm something that an individual does well. Although the goal of a Story should never be to change the individual’s behavior, that individual’s improved understanding of events and expectations may lead to more effective responses." (http://www.thegraycenter.org 2012)

An example of a Social Story from the Gray Center website is:

So what is the difference between a Sensory Story and Social Story? As we have already defined the nature of a Sensory Story (in the above section on this webpage), we will concentrate on providing an explanation of Social Stories such that the distinction between the two might be made explicit.

Carol Gray, former consultant to students with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), first defined Social Stories™ in 1991. Gray defines a social story as describing:

"a situation, skill, or concept in terms of relevant social cues, perspectives, and common responses in a specifically defined style and format. The goal of a Social Story is to share accurate social information in a patient and reassuring manner that is easily understood by its audience. Half of all Social Stories developed should affirm something that an individual does well. Although the goal of a Story should never be to change the individual’s behavior, that individual’s improved understanding of events and expectations may lead to more effective responses." (http://www.thegraycenter.org 2012)

An example of a Social Story from the Gray Center website is:

|

|

"My name is Tommy. I am an intelligent second grader at Cottonwood Elementary School. Sometimes, I have to use the bathroom. This is okay.

Bathrooms need to have a toilet or urinal, and maybe sinks. Sometimes, when people need to find a place to keep something until they need it, they might place it in the bathroom. My teacher keeps her overhead projector in the bathroom when she is not using it to make more room in the classroom. It's okay to store an overhead projector in the bathroom, but usually most bathrooms do not have overhead projectors in them. Sometimes, my teacher uses the overhead projector to teach the children. If she were to bring all the children into the bathroom where the overhead projector is, it would be too crowded! So my teacher brings the overhead projector into the classroom to use it. It's okay to use our bathroom with the overhead projector in it. It's also very okay and intelligent to use our bathroom when my teacher is using the overhead projector with the class. The custodians work very hard to keep our bathrooms clean. They use disinfectant to keep everything nice for the children. If the custodians notice bugs, like spiders, they might use bug spray. Bug spray, and other things that custodians have, are used to keep bathrooms free of spiders and things. People never use overhead projectors to keep an area free of spiders; it just would not work. If I should ever see a bug in the bathroom, it's okay to tell an adult. The adult may know how to use a tissue or toilet paper to get rid of the bug, or we may choose to use another bathroom." |

|

As can be seen, a social story is about a real life event for a real life person. The person does not have to be autistic to benefit. A Social Story seeks to explain to the person (Learner) something about a real event in a way that they can comprehend. It has a positive focus and it is hoped that a Learner's understanding of the story will result in the Learner being better able to deal with the real life event in the future.

There are seven types of sentence that may be used in a Social Story:

There are seven types of sentence that may be used in a Social Story:

|

Descriptive sentences:

Perspective sentences: Directive sentences: Affirmative sentences: Control sentences: Cooperative sentences: Partial sentences: |

are truthful and observable sentences (opinion- and assumption-free) that identify the most relevant factors in a social situation. They often answer "wh" questions.

refer to or describe the internal state of other people (their knowledge/thoughts, feelings, beliefs, opinions, motivation or physical condition) so that the individual can learn how others' perceive various events. presents or suggests, in positive terms, a response or choice of responses to a situation or concept. enhances the meaning of statements and may express a commonly shared value or opinion. They can also stress the important points, refer to a law or rule to reassure the Learner. identifies personal strategies the individual will use to recall and apply information. They are written by the individual after reviewing the Social Story. describe what others will do to assist the individual. This helps to ensure consistent responses by a variety of people. encourages the individual to make guesses regarding the next step in a situation, the response of another individual, or his/her own response. Any of the above sentences can be written as a partial sentence with a portion of the sentence being a blank space to complete. |

How does that differ from a Sensory Story? A comparison of the two on a point by point basis may help to clarify the situation further:

While a Sensory Story is not the same thing as Social Story, it is nevertheless bound by a set of rules that cover its creation and delivery. While it is something of a truism that all rules were meant to be broken, we would suggest that those rules outlined in the following sections are not broken without giving it some thought!

- While Social Stories typically address the needs of an autistic audience (although not necessarily so) Sensory Stories typically address the needs of Learners Experiencing PMLD.

- The focus of a Social Story, as its name would imply, is a social aspect. The focus of a Sensory Story is the sensory aspect.

- Social Stories concern information on real life situations and the Learners role within them. Sensory Stories do not necessarily have to concern real life situations rather attempt to make the content of the story explicit through sensory methodologies for Learners experiencing PMLD.

- A Social Story is typically designed and delivered to meet the needs of an individual Learner (though not necessarily so) while a Sensory Story is typically designed and delivered to meet the needs of a group of Learners (though not necessarily so).

- A Social Story whilst not specifically designed to address behavioural issues (See Gray) nevertheless focuses on raising individual awareness of socially acceptable actions in specific circumstances. A Sensory Story is not typically designed to do this (although it could).

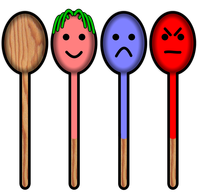

- The goal of Social Stories is to improve an individual's understanding of events and the expectations of others in specific circumstances. A Sensory Story is not typically designed to do this (although it could) but rather focuses of the Learner's understanding of the story itself or, at least, items from within the story ( for example: basic objects {ball}, actions {go}, emotions {happy}, sizes {big}, colours {blue}, etc).

- Social Stories are grounded firmly in reality. Some would allow Sensory Stories to be fantasies (we would differ from that point of view as is explained in a later section). Thus a Sensory Story could be a fairy story, or be about a trip into space, or attempt to bring a classic of English Literature to life (see for example 'Odyssey Now' by Grove & Park 1996)

While a Sensory Story is not the same thing as Social Story, it is nevertheless bound by a set of rules that cover its creation and delivery. While it is something of a truism that all rules were meant to be broken, we would suggest that those rules outlined in the following sections are not broken without giving it some thought!

The Sensory Story Rules

"Although most books were properly constructed, guidelines were barely followed during reading which may negatively influence the effectiveness." (ten Brug, van der Putten, Penne, Maes & Vlaskamp 2011 page 350)

Our experience of present practice in the use of Sensory Stories in the Special Needs Environment with Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties is varied: some aspects of some sessions are extremely good while others are what we would rate as 'not best practice'. So what do we (and others) consider to be best practice in this area and why? We will outline what we consider to best practice in the form of a set of rules and the 'why' we will leave to be detailed in the following sections of this webpage.

Case study: At a school somewhere on the globe, Talksense observed a Sensory Story session which had obviously taken a lot of preparation. It was brilliantly delivered, all the staff present were actively involved and it appeared that the majority of the class were enjoying most of it. It was the sort of session that you might imagine would have obtained an outstanding grade under formal observation. However, Talksense had serious concerns. The story was about a school holiday that a different (and obviously more cognitively able) group of children had taken to another country. It detailed sea journeys and events of which the Learners in the class had no experience. The teacher controlled every aspect of the story and the session. Had Talksense not spoken the language, the session would have been bewildering although it might have been fun as we were whizzed across the room and sprayed with water. The teacher was not reading from a script but appeared to be constructing the story as she went. The pace of the story telling was very lively. The session had many outstanding features, not the least of which was the effort of all all the staff in the preparation and the delivery but it also had several features that we would consider to be less than perfect practice.

Several years of such observations later, of observing 'the Romans in Britain', 'the First World War', 'Hamlet', and other 'productions' for which the staff involved had obviously made extraordinary efforts, it became clear that there ought to be a set of 'rules' or 'guidelines' which might be considered by the staff involved before putting amazing efforts into such productions. The following section outlines what we believe to be a beginning to such 'guidelines': the Sensory Story Rules.

There are a number of rules that should be observed in the creation and telling of a Sensory Story. Of course, rules may be broken but they should be broken with care and with all staff understanding why they are being circumvented. The ten rules below are not explained here but rather each in separate sections below. While you might not agree with every rule, we would urge you to give each some thought in your future practice.

Rule 1: The Goal is Control

Rule 2: SENSE: Repetition with Consistency;

Rule 3: Real and experiential not abstract: 'Do Tell' approach;

Rule 4: Engagement;

Rule 5: Short and Simple Sentence Structure Spoken Slowly;

Rule 6: Use your team

Rule 7: Rote Round Robin Routines R Really Ruinous

Rule 8: Content:

Adverse Adjectives (happy and sad, big and small, rough and smooth);

Normal Nouns;

Prevalent Prepositions;

Various Verbs;

Simple Short Sentences;

Repeated Refrains are ideally everyday; (see rule 2)

Proceed at a Peaceful Pace - Speak Slowly;

Sensory Systems Set - Objects Organised;

Passive Prompting (least to most);

Engaging Everyday Experiences.

Rule 9: Choice is a Voice.

Rule 10: Age Appropriateness: Stages not Ages? No! Preference not Deference!!

Rule 11: Do not include Sensory Cues or Objects of Reference within the Sensory Story that are actually in use in the school WITHOUT actually going to those places within the school: pretence / make belief (in this instance) is confusing. Both OOR and Sensory Cues require real POLE experience (otherwise the procedure will negate establishment's practice effectiveness)

At present, there is a dearth of research studies on Sensory Stories for IEPMLD on which to base good practice. However, all those that have been published use one or more of the the above rules as part of their protocol:

"When considered together, these studies on shared reading suggest that a literacy lesson for students with severe, multiple disabilities

will include an adaptation of a storybook, opportunities for the student to make frequent responses to engage with the book and answer

questions, teacher prompting to promote use of assistive technology and other responses to show understanding, and some individualization

of the read aloud presentation based on the unique characteristics of the student." (Browder, Lee, & Mims 2011 page 341)

The rules are outlined further below.

Our experience of present practice in the use of Sensory Stories in the Special Needs Environment with Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties is varied: some aspects of some sessions are extremely good while others are what we would rate as 'not best practice'. So what do we (and others) consider to be best practice in this area and why? We will outline what we consider to best practice in the form of a set of rules and the 'why' we will leave to be detailed in the following sections of this webpage.

Case study: At a school somewhere on the globe, Talksense observed a Sensory Story session which had obviously taken a lot of preparation. It was brilliantly delivered, all the staff present were actively involved and it appeared that the majority of the class were enjoying most of it. It was the sort of session that you might imagine would have obtained an outstanding grade under formal observation. However, Talksense had serious concerns. The story was about a school holiday that a different (and obviously more cognitively able) group of children had taken to another country. It detailed sea journeys and events of which the Learners in the class had no experience. The teacher controlled every aspect of the story and the session. Had Talksense not spoken the language, the session would have been bewildering although it might have been fun as we were whizzed across the room and sprayed with water. The teacher was not reading from a script but appeared to be constructing the story as she went. The pace of the story telling was very lively. The session had many outstanding features, not the least of which was the effort of all all the staff in the preparation and the delivery but it also had several features that we would consider to be less than perfect practice.

Several years of such observations later, of observing 'the Romans in Britain', 'the First World War', 'Hamlet', and other 'productions' for which the staff involved had obviously made extraordinary efforts, it became clear that there ought to be a set of 'rules' or 'guidelines' which might be considered by the staff involved before putting amazing efforts into such productions. The following section outlines what we believe to be a beginning to such 'guidelines': the Sensory Story Rules.

There are a number of rules that should be observed in the creation and telling of a Sensory Story. Of course, rules may be broken but they should be broken with care and with all staff understanding why they are being circumvented. The ten rules below are not explained here but rather each in separate sections below. While you might not agree with every rule, we would urge you to give each some thought in your future practice.

Rule 1: The Goal is Control

Rule 2: SENSE: Repetition with Consistency;

Rule 3: Real and experiential not abstract: 'Do Tell' approach;

Rule 4: Engagement;

Rule 5: Short and Simple Sentence Structure Spoken Slowly;

Rule 6: Use your team

Rule 7: Rote Round Robin Routines R Really Ruinous

Rule 8: Content:

Adverse Adjectives (happy and sad, big and small, rough and smooth);

Normal Nouns;

Prevalent Prepositions;

Various Verbs;

Simple Short Sentences;

Repeated Refrains are ideally everyday; (see rule 2)

Proceed at a Peaceful Pace - Speak Slowly;

Sensory Systems Set - Objects Organised;

Passive Prompting (least to most);

Engaging Everyday Experiences.

Rule 9: Choice is a Voice.

Rule 10: Age Appropriateness: Stages not Ages? No! Preference not Deference!!

Rule 11: Do not include Sensory Cues or Objects of Reference within the Sensory Story that are actually in use in the school WITHOUT actually going to those places within the school: pretence / make belief (in this instance) is confusing. Both OOR and Sensory Cues require real POLE experience (otherwise the procedure will negate establishment's practice effectiveness)

At present, there is a dearth of research studies on Sensory Stories for IEPMLD on which to base good practice. However, all those that have been published use one or more of the the above rules as part of their protocol:

"When considered together, these studies on shared reading suggest that a literacy lesson for students with severe, multiple disabilities

will include an adaptation of a storybook, opportunities for the student to make frequent responses to engage with the book and answer

questions, teacher prompting to promote use of assistive technology and other responses to show understanding, and some individualization

of the read aloud presentation based on the unique characteristics of the student." (Browder, Lee, & Mims 2011 page 341)

The rules are outlined further below.

The Goal is Control

"Handicapped infants may begin to lose interest in a world that they do not expect to control" (Brinker & Lewis, 1982)

"Learned helplessness occurs when it is unclear to the learner that he or she is able to exert control over the environment.....For many learners, their social history has offered few opportunities to self-select desired objects, people, or activities. At meal times plates are prepared and distributed. Additional serving are provided automatically. Coats are handed out and doors opened when it is time to go. Thus, throughout the day, the caregivers do virtually everything for the learners. Initially, some learners may have attempted to self-select items of interest, but were actively encouraged not to do so." (Reichle, J. 1991 p.141)

"When children who are deafblind are young, and especially if they have additional difficulties, they may experience the world as much too large and complicated for them to exercise any control. Their experience may only be of having things done to them, not of doing things for themselves. They may have objects put in front of them to look at, but may not have any choice in the matter." (Wyman 2000 page 82)

"By providing people with PMLD the opportunities to exert control and actively participate we help to facilitate the development of contingency awareness; the knowledge that you are able to have some effect on the environment. ... If we are to prevent individuals either from resorting to self stimulatory behaviours or from withdrawing completely from the external world then it is essential that we ensure they are able to engage with their world in an active and meaningful way." (Hogg 2009. page 20)

While undoubtedly there are a plethora of goals for standard education, and many of these may have equal relevance to those experiencing PMLD, there is one particular goal that we believe is a vital component of any curriculum designed to prepare Individuals Experiencing PMLD for a better quality of future life: that goal is 'control'.

"The provision of positive control experiences early in life will be a primary factor in helplessness immunization." (Sweeney, L. 1993)

"a high quality of life is one in which people receive individually tailored support to become full participants in the life of the community, develop skills and independence, be given appropriate choice and control over their lives, be treated with respect in a safe and secure environment”. (Emerson et al 1996)

"Empowerment occurs when control, or power, is passed to an individual or group. In rehabilitation, medicine, social work, psychology, education, and many allied disciplines, it is gradually becoming recognized that the healthiest and most effective individuals have personal control and make decisions for themselves with advice and input from others. The belief here is that, for best results overall, final decisions should be made by the individuals who are most closely affected by the decisions." (Brown and Brown 2003 page 227)

"Students become empowered by taking control of their own learning." (Sutcliffe 1990 page 13)

"Good quality support is to do with giving people power." (Virginia Moffat 1996 page 37)

Generally speaking, the more independent people are and the less external control they receive from others, the more satisfied they are (higher quality of life) (See Legault 1992).Thus, a fundamental goal of all special education should be equipping Learners to live as independent a life as possible. This has long been recognised:

"... citizens with a mental retardation have a right to receive such individual habilitation as will give each of them a realistic opportunity to lead a more useful and meaningful life and to return to society." (Bannerman, Sheldon, Sherman, & Harchik 1990)

"even children with profound learning difficulties , given suitable conditions provided by modern technology, can make choices; in this case between sounds, voices, and rhymes provided on speakers. Moreover, they show enjoyment while so occupied and are motivated to further choice making. At the beginning of this chapter, the opinion was expressed that every step on the way to having more control over our lives is worth taking. In the case of these children, opportunity to exert control, however limited, appears to be leading to increased motivation and increasing self-regulation." (Beryl Smith 1994)(Page 5)

In order to meet this goal, staff within special education should be developing ways in which more and more control can be passed to Learners. Staff should rarely ever be doing it 'for' (there are some exceptions to this rule) and should hardly ever be doing it 'with' (again with some exceptions) but, rather, be facilitating individuals to do it for themselves. The goal of control therefore is one in which the Learner is at the centre of all that we do and the role of Significant Others is to help the Learner to take that control. This is just as true within (Sensory) Story time:

"We need to decrease our use of both verbal and non-verbal control strategies. Storytime should be a pleasurable, positive experience for the child, one in which the child is able to exert some control." (Kaderavek& Sulzby 2002)

However, while we may find a philosophical commitment to a particular idea or an approach fairly easy, often it is much more difficult to make that approach a reality. In observing any session involving Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties one should be constantly asking 'who is in control?' If the answer to that question for the majority of the session is other than the Learners involved then something is amiss. In viewing videos of Sensory Story sessions available on the web (for example on YouTube) look to see who is:

Is it possible for the Learners themselves to relate a story and to control all the sensory aspects as it unfolds? Yes it is! With modern technology that is readily available and not too expensive this is not only a possibility but it should be the aim of every specialist establishment to ensure that such equipment is made available to each staff member who is envisaging making use of Sensory Stories during the session. To this end, we have included a complete section on 'necessary equipment' further down on this webpage.

"Learned helplessness occurs when it is unclear to the learner that he or she is able to exert control over the environment.....For many learners, their social history has offered few opportunities to self-select desired objects, people, or activities. At meal times plates are prepared and distributed. Additional serving are provided automatically. Coats are handed out and doors opened when it is time to go. Thus, throughout the day, the caregivers do virtually everything for the learners. Initially, some learners may have attempted to self-select items of interest, but were actively encouraged not to do so." (Reichle, J. 1991 p.141)

"When children who are deafblind are young, and especially if they have additional difficulties, they may experience the world as much too large and complicated for them to exercise any control. Their experience may only be of having things done to them, not of doing things for themselves. They may have objects put in front of them to look at, but may not have any choice in the matter." (Wyman 2000 page 82)

"By providing people with PMLD the opportunities to exert control and actively participate we help to facilitate the development of contingency awareness; the knowledge that you are able to have some effect on the environment. ... If we are to prevent individuals either from resorting to self stimulatory behaviours or from withdrawing completely from the external world then it is essential that we ensure they are able to engage with their world in an active and meaningful way." (Hogg 2009. page 20)

While undoubtedly there are a plethora of goals for standard education, and many of these may have equal relevance to those experiencing PMLD, there is one particular goal that we believe is a vital component of any curriculum designed to prepare Individuals Experiencing PMLD for a better quality of future life: that goal is 'control'.

"The provision of positive control experiences early in life will be a primary factor in helplessness immunization." (Sweeney, L. 1993)

"a high quality of life is one in which people receive individually tailored support to become full participants in the life of the community, develop skills and independence, be given appropriate choice and control over their lives, be treated with respect in a safe and secure environment”. (Emerson et al 1996)

"Empowerment occurs when control, or power, is passed to an individual or group. In rehabilitation, medicine, social work, psychology, education, and many allied disciplines, it is gradually becoming recognized that the healthiest and most effective individuals have personal control and make decisions for themselves with advice and input from others. The belief here is that, for best results overall, final decisions should be made by the individuals who are most closely affected by the decisions." (Brown and Brown 2003 page 227)

"Students become empowered by taking control of their own learning." (Sutcliffe 1990 page 13)

"Good quality support is to do with giving people power." (Virginia Moffat 1996 page 37)

Generally speaking, the more independent people are and the less external control they receive from others, the more satisfied they are (higher quality of life) (See Legault 1992).Thus, a fundamental goal of all special education should be equipping Learners to live as independent a life as possible. This has long been recognised:

"... citizens with a mental retardation have a right to receive such individual habilitation as will give each of them a realistic opportunity to lead a more useful and meaningful life and to return to society." (Bannerman, Sheldon, Sherman, & Harchik 1990)

"even children with profound learning difficulties , given suitable conditions provided by modern technology, can make choices; in this case between sounds, voices, and rhymes provided on speakers. Moreover, they show enjoyment while so occupied and are motivated to further choice making. At the beginning of this chapter, the opinion was expressed that every step on the way to having more control over our lives is worth taking. In the case of these children, opportunity to exert control, however limited, appears to be leading to increased motivation and increasing self-regulation." (Beryl Smith 1994)(Page 5)

In order to meet this goal, staff within special education should be developing ways in which more and more control can be passed to Learners. Staff should rarely ever be doing it 'for' (there are some exceptions to this rule) and should hardly ever be doing it 'with' (again with some exceptions) but, rather, be facilitating individuals to do it for themselves. The goal of control therefore is one in which the Learner is at the centre of all that we do and the role of Significant Others is to help the Learner to take that control. This is just as true within (Sensory) Story time:

"We need to decrease our use of both verbal and non-verbal control strategies. Storytime should be a pleasurable, positive experience for the child, one in which the child is able to exert some control." (Kaderavek& Sulzby 2002)

However, while we may find a philosophical commitment to a particular idea or an approach fairly easy, often it is much more difficult to make that approach a reality. In observing any session involving Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties one should be constantly asking 'who is in control?' If the answer to that question for the majority of the session is other than the Learners involved then something is amiss. In viewing videos of Sensory Story sessions available on the web (for example on YouTube) look to see who is:

- telling the story;

- operating the visual accompaniment (PowerPoint for example);

- activating the switches to create sound effects;

- operating the augmentative communication technology;

- making choices;

- mostly in control!

Is it possible for the Learners themselves to relate a story and to control all the sensory aspects as it unfolds? Yes it is! With modern technology that is readily available and not too expensive this is not only a possibility but it should be the aim of every specialist establishment to ensure that such equipment is made available to each staff member who is envisaging making use of Sensory Stories during the session. To this end, we have included a complete section on 'necessary equipment' further down on this webpage.

Take Twice Daily Until Better: Repetition

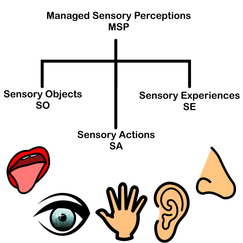

In order for an Individual Experiencing PMLD to comprehend the world out there it must make SENSE:

The world as presented to an Individual Experiencing PMLD will need to be 'structured': that is, another will have to present the part of it they wish the individual to comprehend in such a manner that Learner understanding is feasible (The work of Lev Semyonovich Vygotsky on the 'zone of proximal development' is relevant here as well as that of Jerome Bruner on what he termed 'scaffolding'). This typically means breaking it down into much smaller bite sized chunks before presentation.

"A handicapped child represents a qualitatively different, unique type of development... If a blind or deaf child achieves the same level of development as a normal child, then the child with a defect achieves this in another way, by another course, by other means; and, for the pedagogue, it is particularly important to know the uniqueness of the course along which he must lead the child. This uniqueness transforms the minus of the handicap into the plus of compensation." (Vygotsky, L.S. 1993)

"One of Vygotsky's main contributions to educational theory is a concept termed the 'zone of proximal development'. This he used to refer to the 'gap' that exists for an individual between what he is able to do alone and what he can achieve with help from one more knowledgeable or skilled than himself." (Wood, D. 1988)

"The mother must always be a step ahead, in what Vygotsky calls the 'zone of proximal development'; the infant cannot move into, or conceive of, the next stage ahead except through its being occupied and communicated to him by his mother." (Sacks, O. 1989)

Experience relates to learning that is part of the real world of the individual and not something that they have never known and never will know. Experience of the world is covered in the next section 'Real Lives' and is therefore not detailed here any further.

Numerous means that the process need repeating over and over such that the individual has more than one chance to grasp it. For those Experiencing PMLD this might mean daily encounters with 'scaffolded' material.

Therefore, any Sensory Story must not simply be told just the once but, rather, many times and each time the telling must be the same: it has to be consistent such that the individual has a chance to build on previous encounters and to anticipate forthcoming events.

Finally, in this section, any Learner who is not attending (for whatever reason) is unlikely to comprehend that which is being taught. Thus, both the material and the manner in which the material is presented must engage the Learner. This too is covered in another section of this webpage and therefore will not be detailed further here.

This section of the webpage deals with repetition and consistency both of which are vital ingredients of the mix that go to produce a successful Sensory Story. With repetition comes some chance of comprehension:

"students may need many repetitions with a book to understand the story and be able to produce comprehension responses." (Mims, Browder, Baker, Lee, & Spooner. 2009 page 411)

The word 'repetition' as used within this section of this webpage has two meanings:

"Constant repetition and a great deal of support will be needed to generalise learning into new situations." (MENCAP, 2008, Page 4)

"Repetition provides rehearsal and consolidation of known games and activities, and a continuous secure base and reference points. Through repetition variations occur, leading to new games and activities." (Quest For Learning, 2009, page 41)

"In order to meet their specific learning needs, a curriculum designed for pupils with MSI must provide frequent repetition and redundancy of information" (Murdoch et al, 2009, page 12)

"Remember that short, daily repetition is more valuable than longer, weekly sessions" (Association of Teachers and Lecturers, 2013, page 4)

"Focused on repeating sequences of sensory storytelling with the same three stories told every week for six weeks and then another three stories. The would allow for,the development of a pattern of sensory experiences using voice and body, and words and multi sensory objects." (Dowling, 2011, page 29)

Repetition of the presentation should be at the very minimum once per week although, ideally, it ought to be daily or every other day. This should continue for an entire term before any new Sensory Story is introduced and, thus, a maximum of three Sensory Stories per year is recommended. Of course, if the group has made significant progress and really needs to move on then more than one Sensory Story per term can be attempted. However, movement to another Sensory Story should never be consider to alleviate staff boredom! Progression to a further Sensory Story should depend upon an assessment of the group's ability to comprehend the narrative or, at the very least, specific and targeted aspects of the narrative. Thus staff would be looking for particular behaviours from each member of the group which clearly demonstrate understanding. This is aspect is covered in greater detail further down this webpage.

While "short, daily repetition" (see above quote from ATL) would seem to be a good guide in this matter, we can hear people asking, 'How short is short?'. It is not the same as asking 'how long is a piece of string?' because we do have some boundaries. Obviously, a single Sensory Story must be able to be 'told' within a single session and therefore the length of any of your sessions forms an upper boundary. However, other factors too will have a limiting factor (including but not necessarily a complete listing):