101 ideas for ...

Literacy & AAC

There is a growing awareness of the importance of literacy in AAC supported by an ever increasing amount of presentations, reference materials and publications (see idea 101).

“For persons who are unable to use their speech to help them in their literacy ascent, their AAC system can make a unique contribution to both the instructional scaffolding that supports their learning and the language foundation upon which the scaffolding depends.” Shirley McNaughton (Blissymbolics 2006)

Literacy is important in virtually all aspects of our daily lives. It is fundamental in education, at work, in accessing the internet, in communicating with friends (e-mailing and texting for example), in ordering food off a menu ...

Literacy is an important tool for AAC too. Without it, it is impossible to access the many thousands of fringe words in a language. Without it, the Learner is limited to those fringe words that are provided by the system in use. While fringe words, by definition, may only be required infrequently, never-the-less, when you want to say ‘triceratops’ it is nice to be able to do so without playing twenty questions with the listener.

“Currently, the majority of individuals who require AAC do not have functional literacy skills.” Janice Light (The AAC – RERC Webcast Series 2010)

While there are Learners whose cognitive condition makes it unlikely that they will ever go on to develop emergent literacy skills, it is not our role to play God and simply decide that we will not bother. If we never make any attempt then, by definition, a person has no chance of gaining such skills. How do you win the lottery? You purchase a ticket! Sure, it’s a remote chance but, if you never purchase the ticket, you definitely will not win.

That is not to say that we begin by trying to teach Learners experiencing (for example) Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties the letters of the alphabet! There are experiences which we can provide, as we are developing AAC skills, that will ‘pave the way’ for emergent literacy. Some of these experiences are outlined below.

While the list is not intended to be comprehensive and it is not expected that you will want to use all the ideas, TalkSense always likes to be thorough. So, if you feel that there is anything Talksense has missed out, or there is something we have gotten wrong, or you have another idea, or ...

Let Talksense know!

“For persons who are unable to use their speech to help them in their literacy ascent, their AAC system can make a unique contribution to both the instructional scaffolding that supports their learning and the language foundation upon which the scaffolding depends.” Shirley McNaughton (Blissymbolics 2006)

Literacy is important in virtually all aspects of our daily lives. It is fundamental in education, at work, in accessing the internet, in communicating with friends (e-mailing and texting for example), in ordering food off a menu ...

Literacy is an important tool for AAC too. Without it, it is impossible to access the many thousands of fringe words in a language. Without it, the Learner is limited to those fringe words that are provided by the system in use. While fringe words, by definition, may only be required infrequently, never-the-less, when you want to say ‘triceratops’ it is nice to be able to do so without playing twenty questions with the listener.

“Currently, the majority of individuals who require AAC do not have functional literacy skills.” Janice Light (The AAC – RERC Webcast Series 2010)

While there are Learners whose cognitive condition makes it unlikely that they will ever go on to develop emergent literacy skills, it is not our role to play God and simply decide that we will not bother. If we never make any attempt then, by definition, a person has no chance of gaining such skills. How do you win the lottery? You purchase a ticket! Sure, it’s a remote chance but, if you never purchase the ticket, you definitely will not win.

That is not to say that we begin by trying to teach Learners experiencing (for example) Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties the letters of the alphabet! There are experiences which we can provide, as we are developing AAC skills, that will ‘pave the way’ for emergent literacy. Some of these experiences are outlined below.

While the list is not intended to be comprehensive and it is not expected that you will want to use all the ideas, TalkSense always likes to be thorough. So, if you feel that there is anything Talksense has missed out, or there is something we have gotten wrong, or you have another idea, or ...

Let Talksense know!

Why Learners fail

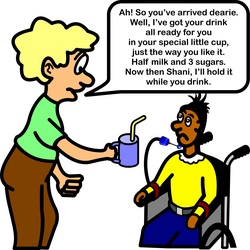

Talksense believes that it is NOT individuals who fail to develop communication skills but, rather, (significant) others who fail to teach the individual to communicate. Too often are practices observed in schools (and beyond) that would stifle the best of us had we been in such a situation. It is a similar problem with literacy, individuals do not fail to acquire at least some of the basic literacy skills simply because they are somehow incapable but, rather, because of the attitudes, expectations, behaviours and practices of Significant Others (Parents, Teachers, Therapists, Classroom Assistants, etc); even those who are well-intentioned. There are also the physical, social, and environmental barriers in an environment which may have a direct impact on a Learner's ability to interact independently with print and may affect the way others behave because of these 'expected' difficulties.

The following is a (non-exhaustive) list of potential reasons for non-acquisition of literacy in Learners of AAC:

- the attitudes and expectations of Significant Others;

- the priorities of Significant Others;

- the behaviours of Significant Others;

- the practices of Significant Others (even those that are well intentioned);

- time pressure on Significant Others leaves little time for teaching literacy;

- the quality of Learner experiences with print and other literacy related issues;

- the sparsity of Learner exposure to print in the environment;

- inability to access libraries and libraries lack of appropriate material;

- physical disability inhibits independent interaction with printed materials;

- cognitive condition means that the Learner does not interact with printed materials (unaided) in an manner that is appropriate to the

development of emergent literacy skills;

- illness and other reasons for poor attendance at school means a lack of consistent tuition in literacy;

- lack of Significant Other awareness of what to do when interacting with a Learner who requires AAC;

- a (genuine) belief that the Learners are incapable of developing such a level of skill therefore 'why waste time in the attempt?'

- not (part of) my job... I'm a teacher of ... I'm a therapist dealing with ... it's xxx's responsibility to do that ...

Teach Communication Not Literacy?

When I began to teach AAC, over 30 years ago now, I believed that literacy, while vitally important, was not my goal. My goal was the development of communication skills and I was really focussed on that specific goal to the exclusion of most others. It wasn't that I believed my pupils/students incapable of learning to be literate, it was more that is was difficult enough a challenge getting them able to communicate let alone being literate at the same time! I believed that they could learn to be literate after they learned to communicate ... indeed, that communication skills were the precursor to most other skills. I was aware that there were other 'powerful' arguments for not teaching literacy to students of AAC:

1. The Learner's cognitive condition precludes the ability to become literate;

2. If we, as teachers, cannot 'play God' and make decisions on what to exclude from a

child's curriculum then we should also be teaching chemistry, physics and Hegellian

Philosophy. Who am I to decide that this particular learner will not go on to be a

professor of philosophy? Surely, by not teaching such studies, I am potentially depriving

the individual of that future?

3. Time given to AAC development is often limited. If literacy and AAC are combined in some way, 'management' might claim that the

time spent teaching literacy is time spent on AAC and therefore, allocate less time directly to the development of AAC skills.

4. Other teachers had already tried and were failing to teach literacy to pupils. If a specialist teacher was incapable of developing

literacy skills in the pupils especially as they were immerse in a culture of literacy, then who am I to think I can do better?

5. Time is short. It's a difficult enough task without making it more difficult.

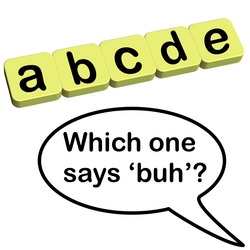

6. If Learner's are finding it difficult to work with symbols then, by definition, they will find it even more difficult to work with the alphabet:

an even more abstract symbol set.

7. Surely language comes before literacy? A child does not first learn to read and write and then begin to speak; they begin speaking

before they become literate.

8. No time to prepare extra resources for literacy on top of all the work I have to do to prepare communication materials.

9. Physical difficulties meant that Learners could not independently interact with print. Who is going to make books available to Learners

as they get older? Time is short... duties are heavy ...

10. No resources for literacy teaching.

11. I wasn't trained as a teacher of literacy. Not my job.

As I said, I used to believe that my goal was communication and not literacy. Furthermore, I used to preach to others that it was not their job either. I offered the above rationales to support this contention. However, I have come to realise, in a Wittgensteinian reversal of logic, that I was wrong (I confess) and that my approach should, as a matter of course, include literacy awareness.

" A confession has to be part of your new life" Ludwig Wittgenstein

Why did I change my viewpoint? Another quote from Wittgenstein will clarify the situation:

"A man will be imprisoned in a room with a door that's unlocked and opens inwards; as long as it does not occur to him to pull rather than push."

I was missing the obvious! Once I began to consider it in a new way, it became clear that I was in the wrong. I missed the fact that I could prepare the way for literacy development by making very simple changes to my approach. I realised that it wasn't necessary (or realistic) to stop doing what I was doing and start teaching 'A,B,C...' but that what I was already doing was preparing the ground for literacy development. Once I started to realise that it was my job to teach literacy (it is everyone's job) then I began to see lots of opportuities to do so. These 'opportunites' did not detract from my principal goal of developing communication skills and did not cause me huge amounts of extra work. Indeed the 'extra' work I did, and the 'extra' resources I prepared, served a communication function also and served me well in teaching AAC!

1. The Learner's cognitive condition precludes the ability to become literate;

2. If we, as teachers, cannot 'play God' and make decisions on what to exclude from a

child's curriculum then we should also be teaching chemistry, physics and Hegellian

Philosophy. Who am I to decide that this particular learner will not go on to be a

professor of philosophy? Surely, by not teaching such studies, I am potentially depriving

the individual of that future?

3. Time given to AAC development is often limited. If literacy and AAC are combined in some way, 'management' might claim that the

time spent teaching literacy is time spent on AAC and therefore, allocate less time directly to the development of AAC skills.

4. Other teachers had already tried and were failing to teach literacy to pupils. If a specialist teacher was incapable of developing

literacy skills in the pupils especially as they were immerse in a culture of literacy, then who am I to think I can do better?

5. Time is short. It's a difficult enough task without making it more difficult.

6. If Learner's are finding it difficult to work with symbols then, by definition, they will find it even more difficult to work with the alphabet:

an even more abstract symbol set.

7. Surely language comes before literacy? A child does not first learn to read and write and then begin to speak; they begin speaking

before they become literate.

8. No time to prepare extra resources for literacy on top of all the work I have to do to prepare communication materials.

9. Physical difficulties meant that Learners could not independently interact with print. Who is going to make books available to Learners

as they get older? Time is short... duties are heavy ...

10. No resources for literacy teaching.

11. I wasn't trained as a teacher of literacy. Not my job.

As I said, I used to believe that my goal was communication and not literacy. Furthermore, I used to preach to others that it was not their job either. I offered the above rationales to support this contention. However, I have come to realise, in a Wittgensteinian reversal of logic, that I was wrong (I confess) and that my approach should, as a matter of course, include literacy awareness.

" A confession has to be part of your new life" Ludwig Wittgenstein

Why did I change my viewpoint? Another quote from Wittgenstein will clarify the situation:

"A man will be imprisoned in a room with a door that's unlocked and opens inwards; as long as it does not occur to him to pull rather than push."

I was missing the obvious! Once I began to consider it in a new way, it became clear that I was in the wrong. I missed the fact that I could prepare the way for literacy development by making very simple changes to my approach. I realised that it wasn't necessary (or realistic) to stop doing what I was doing and start teaching 'A,B,C...' but that what I was already doing was preparing the ground for literacy development. Once I started to realise that it was my job to teach literacy (it is everyone's job) then I began to see lots of opportuities to do so. These 'opportunites' did not detract from my principal goal of developing communication skills and did not cause me huge amounts of extra work. Indeed the 'extra' work I did, and the 'extra' resources I prepared, served a communication function also and served me well in teaching AAC!

PAGE UNDER DEVELOPMENT

Sorry, but this page is still under development.

You can, of course, take look at what is below but it will not be complete while this symbol remains in place!

101 ideas ....

There now follows 101 suggestions, ideas, pointers, .... for developing literacy at one and the same time as the development of communication. If you have any other suggestions, comments, ctiticisms (steady!), or just wish to talk with Talksense about someone or some way to approach a situation, please get in touch using the form at the bottom of this web page.

The ideas are grouped into categories to make them easier to locate:

1. Basics;

2. Phonological Awareness;

3.

4.

5.

6.

Basics

Idea # 1: Immerse the Learner in print

Simple ideas are the best! This one should be is pretty obvious to all ...

In order to be good at doing something, you have to start to do it. If a child never interacts with print then s/he will never become literate. Don't be afraid of engaging all children in the world of print. Each child will benefit from the experience in their own way.

Learners (people who use AAC) need to interact repeatedly with print from as early an age as possible.

Learners need to interact with almost any source of printed material. These ‘sources’ need to be motivating (interesting) for the Learner. For example, it is no use a 'facilitator' reading the Encyclopaedia Britannica to a Learner from beginning to end unless the Learner finds it particularly motivational. What is motivational to an adult may not be motivational to a child.

Opportunities to interact with simple, bright and colourful, motivating, age-appropriate reading materials (books, comics, magazines ...) on a regular basis, from as early age as possible is, therefore, extremely important. Interacting means not just listening, but being actively involved:

- being able to choose the texts;

- being able to see and follow the text as it is read,

- being assisted to understand the story line (pictures, sensory stories, object cues ...);

- being able to comment on the text;

- being able to' instruct' the reader;

- being able to join in at appropriate moments;

- having repeated access to the same text;

- making sounds as appropriate during the reading of a text;

- having opportunities to rhyme words in a text;

- having fun!

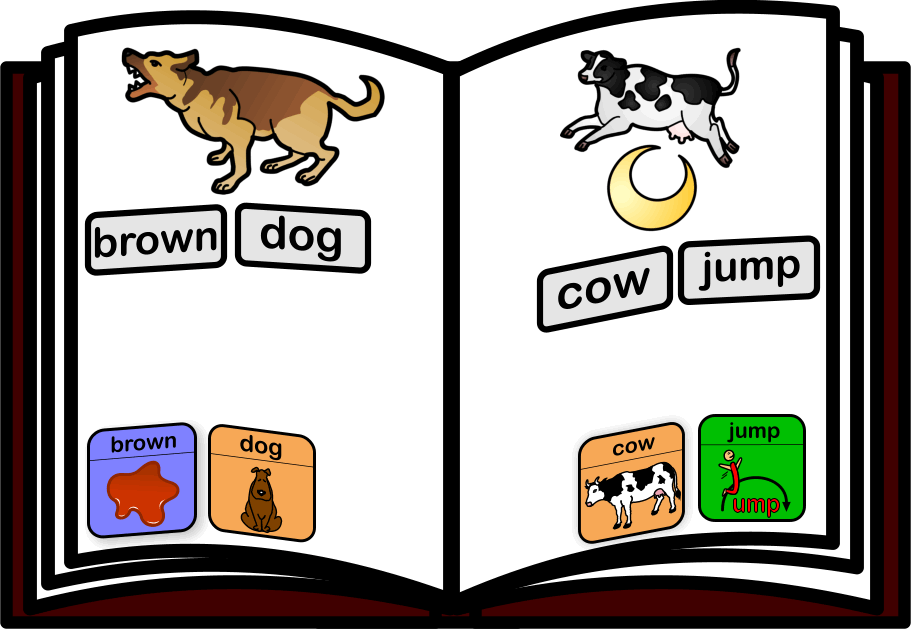

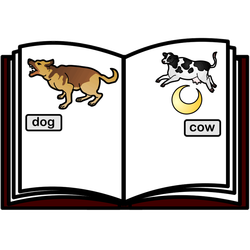

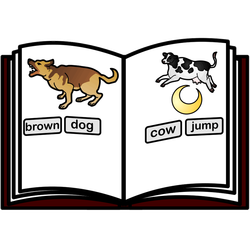

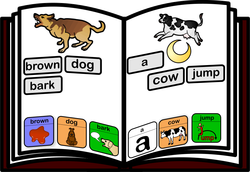

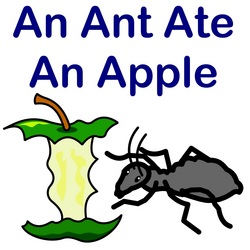

Idea # 2: As you teach AAC - teach Literacy,

As you teach Literacy - teach AAC!

The cartoon depicts a teacher informing his class of the 'four R's': included is the new 'R' ... Rabbiting, which is a British colloquial term for talking a lot. The point being made is that the two areas of study 'literacy' and 'AAC' are not mutually exclusive but, rather, as you teach one you are almost certainly going to touch on the other even if you do not put any effort into it. It follows, therefore. if you put a little effort into ensuring that the one is included with the other you (and, more importantly, the Learenrs) will reap great benefits.

The Learner who is literate will find accesssing fringe vocabulary an easier process than the Learner who is not. Most AAC systems provide ready access to core vocabulary, it's the fringe words that are harder (if not impossible) to reach. As most AAC systems offer some form of vocabulary prediction system through spelling ... all words are obtainable within a few key strokes.

Adding literacy into AAC does not require hours of extra work, it just means that as you prepare for one you need to pay a little attention to the other. Resources for AAC can become resources for literacy and resources for literacy can become resources for AAC. It does NOT double the work load: It is simply working smarter not harder!

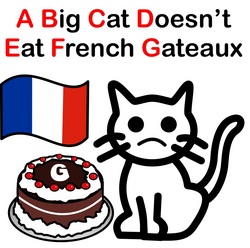

Idea # 3: Core Vocabulary Beginnings

There are words in any language that are used more frequently than others . The list of such words is very similar whether we are talking about spoken or written language. The first 500 words on the list are generally independent of age, sex, occupation, time of day or year, and even topic of conversation! The biggest collection of English vocabulary in the world is the Oxford English Corpus. It may surprise you to know that, in this collection of over two billion words, just TEN (root) words make up 25% of the total and 100 (root) words 50%. Words such as 'I','you','it', 'do', 'have' appear in almost every sentence and, once we list the top 100 words, it is almost impossible to compose a sentence that does not include at least one of them. It is therefore important for language learning and for literacy that these words feature prominently in all that we do. We should not be simply focusing on a list of nouns because, believe it or not, there are actually very few nouns in the top 100 most frequently used words! For a comprehensive listing of core vocabularies in English go here.

That is not to say we should ignore Fringe (the opposite of Core) Vocabulary. Many children's books contain a lot of such words (monster, cat, bear, hunt, caterpillar ...). We cannot ignore them! However, look at the Core Vocabulary contained in the following sentence, 'We are going on a bear hunt' ... the first five words are Core, the last two are Fringe. Once the child finishes with that particular book, how many times is s/he likely to encounter the words 'bear' or 'hunt'? Pick up another child's book and look for them in it ... you are unlikely to find them. Thus, while we cannot ignore them: 'We are going on a ...' has little meaning without the concluding Fringe words (we could use, 'We are going to look for an animal' to keep it all in Core), we should not focus exclusively on (Fringe) nouns at the beginning, even though it is very tempting to do so because they are usually easier to teach. The opposite is also true: we should not focus on Core and ignore the fringe - rather, a healthy balance between the two is advocated.

Idea # 4: Engineer the environment for AAC and Literacy

In order to support both the development of AAC and Literacy, it is advisable to 'Engineer the Educational Environment'. Environmental Engineering is a grand way of saying that the environment should be organised in ways that will both promote and support (not inhibit) the skills we are seeking. It doesn't necessarily mean that you have to knock down walls and rebuild the structure as the teacher in the cartoon is suggesting! However, it may mean re-organizing the way a particular room's furniture is arranged.

There are many ways in which the environment can be engineered to support the development of both AAC and literacy, some of which are covered in the ideas that follow. I would like to say 'all of which are covered in the ideas that follow' but that would assume I have covered every idea conceivable!

Ideas (covered at some point below) include:

|

In accordance with TalkSense's principles, I have just organised a little Environmental Engineering for the school. Shouldn't disrupt things too much!

|

- Labelling the environment;

- Symbol and Text Displays; - Exit the Room Requests; - Accessible and inclusive Libraries; - Canteen Communication |

Idea # 5: Choose books with repeated story lines

Books with repeated story lines are typically good to use with Learners who are developing emergent literacy skills. The Reader can provide the Learner with a means to say the repeated line (V-Pen and symbol, BIGmack, SGD, other AAC system) and then encourage the Learner to use the system to say the line at the appropriate time. It may be that the Reader pauses, looks expectantly at the Learner, then at the AAC system in order to prompt for the line until the Learner is doing it for him/herself.

Generally, the rule is that, such ‘prompts’ should go from the least intrusive to the most intrusive: therefore, physically taking the Learner’s hand and facilitating him/her to access the AAC system should be among the very last strategies adopted.

There are lots and lots of books with repeated story line. Spend some time browsing in your local children's book store! Take a look at the 'that's not my ...' series by Fiona Watt

(Usborne touchy-feely books)

Not now Bernard Oh no! But he was still hungry We're going on a bear hunt

I can't stand this he ate through We're gonna catch a big one

I can't stand this he ate through We're gonna catch a big one

Children's Books with repeated story lines. Many are available through Amazon (search for the title). Lots are available in varying languages (including Chinese)

|

Aardema, V.

Aliki Aliki Alborough, J. Alborough, J. Alborough, J. Alborough, J. Allen, P. Allen, R.V. Allen, R.V. Archambault, J & Martin, Jr. B. Asch, F. Asch, F. Asch, F. Asch, F. Asch, F. Asch, F. Asch, F. Asch, F. Asch, F. Asch, F. Asch, F. Asch, F. Asch, F. Asch, F. Asch, F. Asch, F. Astley, J. Aylesworth, J. Aylesworth, J. Baer, G. Baker, A. Baker, K. Barrett, J. Barton, B. Becker, J. Bennett, J. Blackall, S. Blackstone, S. Blake, Q. Boniface, W. Boynton, S. Boynton, S. Boynton, S. Boynton, S. Brandenberg, F. Brown, M.W. Brown, M.W. Brown, M.W. Brown, R. Burningham, J. Burningham, J. Butler, D. Campbell, R. Campbell, R. Campbell, R. Campbell, R. Carle, E. Carle, E. Carle, E. Carle, E. Carle, E. Carle, E. Carle, E. Carle, E. Carle, E. Carle, E. Carle, E. Carlson, N. Carlson, N. Carlstrom, N.W. Cartwright, S. Christelow, E. Colandro, L. Colandro, L. Colandro, L. Colandro, L. Colandro, L. Colandro, L. Colandro, L. Colandro, L. Colandro, L. Cooney, B. Cowley, J. Cowley, J. Cowley, J. Coxe, M. Croser, J. & Vassiliou, S. Dale, P. Day, D. Delany, A. De Regniers, B.S. De Regniers, B.S. Dijs, C. Droyd, A. Dodd, L. Dodd, L. Doyle, C. Dugan, B. Dunbar, J. Eastman, P.D. Emberley, B. Emberley, E. Ernst, L.C. Falconer, E. Falwell, C. Faulkner, M. Flack, M. Fox, M. Fox, M. Fox, M. Fox, M. Framst, L. Framst, L. Freymann, S. Gag, W. Galdone, P. Galdone, P. Galdone, P. Galdone, P. Galdone, P. Gale, L. Gelman, R.G. Gilman, P. Ginsburg, M. Golden Books Golden Books Gordon, J. R. Grabien, D. Gravett, E, Greeley, V. Grindley, S. Grindley, S. Guarino, D. Guy, G. F. Hamsa, B. Hawkins, C. Hayes, S. Hennesy, B.G. Henkes, Kevin Hill, E. Hoberman, M. Hogrogian, N. Holzwarth, W. & Erlbruch, W. Hopgood, T. Hutchins, P. Hutchins, P. Hutchins, P. Hutchins, P. Hutchins, P. Hutchins, P. Hutchins, P. Ivimey, J. Jindrich, J. Johnson, T. Jonas, A. Joosse, B. Jovanovich, H. Kahn, J. Kalan, R. Kalan, R. Kellogg, S. Kent, J. King, B. King-DeBaun, P. King-DeBaun, P. Knowles, T. Koontz, R. Kovalski, M. Kraus, R. Kraus, R. Kraus, R. Kraus, R. Kraus, R., & Aruego, J. Krauss, Ruth Krauss, Ruth Langstaff, J. Langstaff, J. Lawston, L. Lewis, K. Lewis, K. Lindbergh, R. Lindbergh, R. Livingston, M. Lobel, A. Lobel, A. Locker, T. Lockwood, P. & Vulliamy, C. Long, M. Maxner, J. MacDonald, E. Marshall, J. Martin, B. Martin, B. Martin, B. Martin, B. Martin, B. Martin, B. Masurel, C. & Henry, M.H. Mayer, M. Mayer, M. Mayer, M. Mayer, M. Mayer, M. Maxner, J. McBratney, S. McGilvray, R McGuire, L. McKee, D. McKissack, F. & P. McKissack P. and Clovis,M McNair, P., & Shioleno, C. Melville, H. Metzger, S. Miller, S.S. Miranda, A. Mosel, A. Most, B. Most, B. Munsch, R Munsch, R. Munsch, R. Munsch, R., & Martchenko, M. Murphy, J. Myers, T. Neitzel, S. Nelson, J. Numeroff, L.J. Parr, T. Patricelli, L. Patricelli, L. Peek, M. Peppe, R. Pereira, L. & Solomon, M. Perkins, A. Pienkowski, J. Pienkowski, J. Pienkowski, J. Pienkowski, J. Pizer, A. Pomerantz, C. Pryor, A. Quackenbush, R. Raffi Raffi Raschaka, C. Rathmann, P. Reader's Digest Rice, Eve Rice, Eve Roach, V.A. Roach, V.A. Roach, V.A. Roach, V.A. Roach, V.A. Roach, V.A. Roach, V.A. Roach, V.A. Robart, R. Roberts, J.M. Roffey, M. Rogers, P. Rosen, M. & Oxenbury, H. Ross, T. Saltzberg, B. Sawicki, N. J. Scieszka, J. Sendak, M. Sendak, M. Serffozo, M. Seuss, Dr. Seuss, Dr. Seuss, Dr. Shannon, G. Shannon, G. Shaw, C.B. Shiefman, V. Sloat, T. Slobodkina, E. Stead, P. Stevens, H. Stevens, J. Suteev, V., Dewey, A., Aruego, J., & Ginsburg, M. Swanson, S.M. Taback, S. Tafuri, N. Tyler, J. & Hawthorn, P. Van Laan, N. Van Laan, N. Van Laan, N. Viorst, J. Vipont, E. Voce, L. Waber, B. Waddell, M. Waddell, M. Waddell, M., & Firth, B. Wadsworth, O. Watanabe S. Watt, F. West, C. West, C. West, C. West, C. West, C. West, C. West, C. Westcott, N. White Carlstrom, N. Wilburn, K. Williams, L. Williams, S. Wilson, K. & Chapman, J. Wing, N. Winters, K. Wolff, F. & Kozielski, D. Wolkstein, D. Wood, A. Wood, A. Wood, A. Wood, J. Wylie, J. and D. Wylie, J. and D. Yolen, J. Zimmerman, Andrea Zimmermann, H. W. |

Why Mosquitos Buzz in People's Ears

Go Tell Aunt Rhody My five senses. Hug Yes Tall Where's My Teddy? Bertie and the bear I Love Ladybugs The Dinosaur Land A Beautiful Feast for a Big King Cat Goodbye House Happy Birthday, Moon Here Comes The Cat Just Like Daddy Monkey face. Moonbear's Bargain Moonbear's Canoe Moonbear's Dream Moonbear's Friend Moonbear's Pet Moonbear's Shadow Moonbear's Skyfire Mooncake Moondance Moongame Popcorn When one cat woke up Naughty Little Monkeys Old Black Fly Thump, Thump, Rat-a-Tat-Tat Two tiny mice Who is the beast? Animals Should Definitely Not Act Like People Dinosaurs, dinosaurs Seven little rabbits. Teeny Tiny Knock, Knock Bear on a Bike Mr. Magnolia Five Little Ghosts Blue Hat, Green Hat Doggies Moo Baa La La La Yellow Hat, Red Hat Aunt Nina, good night Goodnight Moon Home for a bunny The Important Book A Dark, Dark Tale Mr. Gumpy's Outing Mr. Gumpy's Motor Car A Happy Tale Dear Santa Dear Zoo It's mine Oh Dear 1, 2, 3 to the Zoo Do You Want To Be My Friend? Have You Seen My Cat? Rooster's Off to See the World The Bad Tempered Ladybird The mixed-up chameleon The secret birthday message The Very Busy Spider The Very Hungry Caterpillar The Very Quiet Cricket Today is Monday I Like Me How to Lose All Your Friends Jesse Bear, What Will You Wear? Who's Making That Mess? Five Little Monkeys Jumping on the Bed There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Bat There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Bell There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Chick There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Clover There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Rose There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Shell There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed Some Books There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed Some Leaves There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed Some Snow Miss Rumphius Mrs. Wishy-Washy The Tiny Woman's Coat Who Will Be My Mother Whose Footprints? Stuck in the Mud Ten in the Bed King of the Woods Gunnywolf Going for a Walk How Joe the Bear and Sam The Mouse Got Together Are You My Mommy? Goodnight iPad Hairy Maclary from Donaldson's Dairy Hairy Maclary Scatter cat You Can't Catch Me Let's Go Shopping Four Fierce Kittens Are You My Mother? Drummer Hoff Klippity klop Up to Ten and Down Again The house that Jack built Shape Capers Jack and the Beanstalk Ask Mr. Bear Hattie and the Fox Shoes From Grandpa Time For Bed Whoever You Are Kelly's Garden On My Walk Knock, Knock Millions of cats Henny Penny The Gingerbread Man The Teeny, Tiny Woman The Three Billy Goats Gruff The Three Little Pigs The Animals of Farmer Jones I Went to the Zoo Jillian Jiggs The Chick and the Duckling The Little Red Hen The Three Little Pigs Two Bad Babies A Dark, Dark Tale Wolf Won't Bite Where's My Share? Don't Rock the Boat! Knock, Knock! Who's There? Is Your Mama A Llama? Black Crow, Black Crow Dirty Larry Old Mother Hubbard This is the Bear and the Picnic Lunch Jake Baked the Cake Kitten's First Full Moon Where's Spot? A House is a House for Me One fine day The Story of the Little Mole . Wow! Said the Owl 1 Hunter Little Pink Pig Rosie's Walk Ten Red Apples The Doorbell Rang Titch We're Going on a Picnic! Three Blind Mice But that wasn't the best part Yonder Color dance Mama, do you love me? Mike's Kite You Can't Catch Me Jump, Frog, Jump! Stop, Thief! Pinkerton behave! The Fat Cat Sitting on the Farm Storytime Storytime, Just For Fun! No, Barnaby This Old Man The Wheels on the Bus Come Out and Play Leo the Late Bloomer Noel the Coward Where are You Going, Little Mouse? Whose mouse are you? Big and Little The Carrot Seed Oh, A-Hunting We Will Go Ol' Dan Tucker Can You Hop? Chugga Chugga Choo Choo Tugga Tugga Tugboat The Day the Goose Got Loose There's a Cow in the Road! Dilly Dilly Piccalilli A treeful of pigs The Rose in My Garden Catskill Eagle Cat Boy! How I Became a Pirate Nicholas the Cricket Mike's Kite The Three Little Pigs Brown Bear, Brown Bear, what do you see? Chicka Chicka Boom Boom Fire! Fire! Said Mrs. McGuire Good Night, Mr. Beetle Polar Bear, Polar Bear, what do you hear? The Braggin' Dragon Good Night! Baby Sister Says No I Was So Mad Just For You Me, Too What Do You Do With a Kangaroo? Nicholas the Cricket Guess How Much I Love You Don't Climb Out of the Window Tonight Brush Your Teeth Please Not Now Bernard Constance Stumbles Who is coming? Quick Tech Readable, Repeatable Stories and Activities Catskill Eagle Five Little Sharks Swimming in the Sea Three Stories You Can Read to Your Dog To Market, To Market Tikki Tikki Tembo If the Dinosaurs Came Back The cow that went OINK. Love You Forever Mud Puddle Mortimer Moira’s birthday. Peace at Last Good Babies: A Tale of Trolls, Humans, a Witch and a Switch The Jacket I Wear in the Snow Peanut Butter and Jelly If You Give a Mouse a Cookie We Belong Together: A Book About Adoption and Families Quiet Loud Yummy Yucky Mary Wore Her Red Dress The House That Jack Built Oh! A Bubble… Hand, Hand, Fingers, Thumb Eggs for Tea Little Monsters Pet Food Phone Book It's A Perfect Day Flap your wings and try The Baby Blue Cat Who Said No She'll Be Comin' Round the Mountain Five Little Ducks The Wheels on the Bus Yo! Yes? Good Night, Gorilla Brush Your Teeth Please Goodnight, Goodnight Grammy's House A dream in a wishing well At the Carnival At the zoo Chasing butterflies I can spell dinosaur I Love Ladybugs Ten Times Three dogs at my door The Cake That Mack Ate King of the Wood I spy at the zoo What's Wrong with Tom? We're Going on a Bear Hunt Super Dooper Jezebel Peekaboo Kisses The Little Red House The True Story of the Three Little Pigs! Pierre Chicken Soup With Rice Who Said Red? My Many Coloured Days Green Eggs and Ham The Cat in the Hat Dance Away The Piney Woods Peddler It Looked Like Spilt Milk Sunday Potatoes, Monday Potatoes The Thing That Bothered Farmer Brown Caps For Sale A Sick Day for Amos McGee The Fat Mouse The House That Jack Built The chick and the duckling The House in the Night Joseph Had a Little Overcoat Have You Seen My Duckling? Who's Making That Mess? A Mouse in my House Possum Come A-Knocking The Big Fat Worm Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day The Elephant and the Bad Boy Over in the meadow: A traditional counting rhyme. Bearsie Bear and the Suprise Sleepover Party Owl Babies Sailor Bear Let's Go Home Little Bear Over in the Meadow How Do I Put It On? That's not my series (Usborne Touchy Feely Books) “Buzz, Buzz, Buzz” Went Bumblebee Have You Seen the Crocodile? Hello, Great Big Bullfrog! I Bought My Love a Tabby Cat I Don't Care! Said the Bear "Not Me", Said the Monkey "Pardon?" said the giraffe I Know an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly Jesse Bear, What Will You Wear? The Gingerbread Boy The Little Old Lady Who Was Not Afraid of Anything I Went Walking Bear Snores On Hippity Hop, Frog on Top On My Walk On Halloween Night Step By Step King Bidgood's in the Bathtub Silly Sally The Napping House Moo, Moo, Brown Cow A Big Fish Story A More or Less Fish Story Owl Moon Trashy Town Henny Penny |

The above list may be comprehensive but is NOT exhaustive. If you know of any other children's books with repeated story lines please let Talksense know and we will add them to the list.

Idea # 6: Choose books with large print

Studies have shown books with larger bolder print (20 point font or larger) encourage more Learner interaction with the the printed word (see, for example Ezell & Justice (2000); Justice & Ezell (2000)). As promoting interaction with print is what we desire, it is advisable to look for books with larger print and fewer words per page. There will be a lot of variation in the print size in the books that are available in any classroom and or home. As such, not every available book will hold the same ability in this area.

Having fewer words per page (an average of five or less is recommended: see Justice, L.M., & Kaderavek, J. 2002) also assists Learners to focus more easily on the salient features of letters and words and, as such, helps promote word recognition.

If the same word appears frequently throughout a text Learners are more likely to begin to recognise it then words that only appear once. As such (and as has already been suggested), stories with either repeated story lines or stories that use the same word or words on each page may be preferable.

It is also advisable (as can be seen below) to let the Learner choose the book that s/he would like to read together with a Significant Other. It should be interesting to see what style of book (big pictures, big print, lift the flap, etc) your Learners will choose.

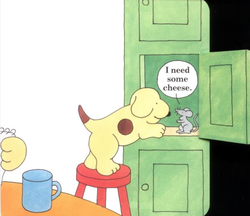

Idea # 7: Choose stories with embedded text

Research has shown that young children's eyes will fixate more on text that is embedded within images than the narrative text even if the narrative text is large and emboldened (see, for example, Justice & Lankford (2002)). Embedded text has also been shown to promote more spontaneous utterances from Learners (see Ezell & Justice (2000)).

Embedded text is text that forms part of the picture or pictures on the page rather than text above, below or to one side of the image. For example, in the image from Eric Hill's 'Spot bakes a cake' (Hill, 1994, Frederick Warne Publishers Ltd), the mouse is saying, "I need some cheese". There are many children's books with examples of embedded text within images and it is worthwhile in keeping an eye out for them while browsing in book stores on on line.

Examples of such books for adults are not as easy to find and staff may need to create their own materials. However, there lots of comic books out there that do exactly this and many of these are read by adults (the super hero ones for example). It should be possible to enlarge selected images from purchased comic books for use with a particular Learner in an educational environment.

Idea # 8: Let the Learner choose the texts

Typically, when children choose stories for an adult to read to them, they do not choose a different story every time but, and quite often to the annoyance of some adults, they might select the same story over and over again until they can almost predict every word as it is spoken. According to Erickson and Koppenhaver (2006), typically developing children hear their favourite story between 200 and 400 times and, as they do, they begin to interact with it more and more until they are in command. The non-speaking child, especially those with additional cognitive deficits, often cannot insist on the same book and, therefore, when Significant Others (quite naturally) choose a different book each time to read, they are unwittingly depriving the child of a very important source of learning.

Therefore, it is important that the reader allow the Learner to choose the text (the choice should always include previously read items). A repeated experience of the same material over and over is essential for the progress of some Learners. Being able to predict coming words and seeing the actual text means that a child can start to equate a particular piece of text to a particular word sound. It helps enormously, in this matter, if the adult finger-points to the words as s/he is reading.

An idea is to turn the front cover pictures of the book choices into symbols. These symbols can be used to allow the learner to make a choice of books at a later stage. Such symbols can be almost as large as the book itself to begin but, after successful use, they can be gradually reduced in size to allow them to be placed within the grid on a communication board (communication book, dynamic display, ...) such that the Learner can request a book without actually being in the presence of books. If colour coding is used then some Learners might find it easier to indicate a particular choice.

Therefore, it is important that the reader allow the Learner to choose the text (the choice should always include previously read items). A repeated experience of the same material over and over is essential for the progress of some Learners. Being able to predict coming words and seeing the actual text means that a child can start to equate a particular piece of text to a particular word sound. It helps enormously, in this matter, if the adult finger-points to the words as s/he is reading.

An idea is to turn the front cover pictures of the book choices into symbols. These symbols can be used to allow the learner to make a choice of books at a later stage. Such symbols can be almost as large as the book itself to begin but, after successful use, they can be gradually reduced in size to allow them to be placed within the grid on a communication board (communication book, dynamic display, ...) such that the Learner can request a book without actually being in the presence of books. If colour coding is used then some Learners might find it easier to indicate a particular choice.

Idea # 9: Talk about the items in the text as you read

It is good practice, while reading to a Learner, to talk about and around the text and relate it to the Learner’s own experiences and knowledge. For example, 'Fringe' vocabulary words often pop up in children’s stories (adventure, dragon, bear, hunt, caterpillar, etc). It should be remembered that many Learners will have limited experiences of the real world and may not really be cognisant of such ‘fringe’ words. If we can illustrate these items and make them accessible to the Learner then we assist the understanding of the text, the print, as well as making the story a more enjoyable experience.

Here is a Chinese 'fringe' vocabulary word:

毛蟲

If you are not literate in Mandarin Chinese, you will not recognise it.

If however, I relate it to a picture ( below), it’s meaning becomes apparent. However, if I have never seen a caterpillar before, it is still not as comprehensive an experience as if I saw a caterpillar crawling on a leaf in my garden or, if I do not have a garden, in the park. There are Learners who do not know that milk comes from a cow or that chips (French fries) come from potatoes. I have experience of Learners who did not know the colour of burnt toast: because, as it was always prepared for them, if it was burnt, it was thrown away and a new piece of bread was toasted to perfection!

Bringing stories to life is a lot of fun for both the reader and the Learner. It can encompass many aspects of a school curriculum not just the development of literacy skills! Of course, you do not always have to illustrate every ‘fringe’ item of vocabulary with real objects: I have never actually seen a dragon but I know something about them! Seeing them in pictures in books and watching them in films helped develop my concept enormously.

In order to become literate, it is important that a person has a growing awareness of ‘language’ not just a set of ‘functional communication skills’. An awareness of language necessarily means some understanding of the meanings of words (semantics), how words can change their structure to take on a particular aspect of meaning (morphology), and how the words are put together (syntax). Interacting with the printed page is a first step on this road.

Idea # 10: Assist the Learner to follow the words as you read.

It is important that stories should not just be read: the Learner must be assisted to follow the text so that s/he can begin to associate aparticular sound with a particular letter combination and to understand that the funny little squiggles on the page are actually the things that tell the story.

There are several ways of assisting a Learner to follow text as you read. The most obvious one is to point to each word as you progress through the story. Occasionally, you can pause and (pretend) that you are having a little difficulty with a word and sound it out aloud! The Learner can see and hear how the word is constructed and how you are doing what you are doing: it's not magic, it's just knowing how those squiggles fit together to make sounds... well that and, perhaps, a little bit of magic!

How else could you assist a Learner to follow the text as you read? Here are just a few ideas:

- Prop up the book so that the Learner can clearly see it and your hands are free.

- Highlight each word with a laser pen. Your hand does not get in the way.

- Wear a glove puppet and let the puppet do the pointing to the words.

- Create a cut out creature or other favourite object (for example - rocketship) with a clear 'pointy bit' and let the creature point to the

words as you read.

- Other? If you have other ideas for this area, please contact me and let me know so that they can be added for all to share.

Idea # 11: Make reading time a quality experience for the Learner

In the cartoon, the teacher is going a little over the top in attempting to make the reading experience 'special' for the Learner. He has provided soft music background, a glass of wine (non-alcoholic, of course!), chocolate biscuits, and a choice of reading material and is still trying to add to the quality of the experience. He has the right idea but moving down the wrong road!

In order that a Learner will come to love literacy lessons, it is up to Significant Others to provide a quality experience. It should be:

- Cosy, Comfortable, with increasing Learner Control;

- Friendly and Fun;

- Safe as well as Something to look forward to;

- Exciting and with reader Enthusiasm;

- Variable (not quite the same each time);

- Motivating.

Perhaps a 'special' area can be set up which is used for literacy development. We need to ask how can we make the area and the Learner's time in the area special: one to which the Learner looks forward each day. Some of the other ideas on this page relate directly to this point and may provide inspiration for the quality of experience.

For parents, it can be a time when parent and child can get close and cuddle up cosily to read together, with the parent providing access to AAC as well as focusing on the development of literacy skills.

Idea # 12: Repeat the same story with slight variety.

Research has shown that we typically require thousands of repetitions in order to master a motor task. Each repetition will likely vary slightly from others. Earlier (see above), it was noted that, in normal circumstances, children will demand to read the same book over and over again (maybe hundreds of times) as they increasingly feel confident about participating and then controlling the course of the reading. If we vary the text slightly each time it is read then, it keeps the story fresh and interesting and, allows the child to see that reading is a lot of fun. How would we vary a story? We might:

- act out parts of the story together;

- use different character voices;

- introduce props (sensory stories);

- introduce symbols;

- get others involved when possible;

- allow the Learners to make decisons about some aspect of the story;

- encourage the Learner to interact and control the way the story is told.

Idea # 13: Allow the Learner to choose the Reading Location

We need to give Learners more choice and more control (see item on control lower down this page). They can not only pick the story they want read and exert some control over the direction of the story (see below) but they should also be allowed to choose where they want to listen to and share in the story with the Significant Other.

Children (and adults) enjoy reading in different places: in a chair, on the floor, out in the garden, sat on cushions, ... Therefore, we should offer Learners a choice of where they would like to read as it provides the Learner with more control and can help to heighten the pleasure derived from the reading experience.

To avoid a learner saying 'Disney Land' as in the cartoon (!) a set of option symbols might be presented from which to pick: options which the Staff Member/ Significant Other knows s/he can deliver!

Idea # 14: Allow the Learner to determine the direction of some stories

By using simple choice communication cards which can either be selected by pointing or attached to BIGmacks or equivalents, the Learner can be encouraged to interact with the story line and effect it in some way which does not significantly alter the story's flow. For example, if the story includes a meal, the learner could decide what the characters have to eat or drink. In most stories there will be some aspect that the Learner can control and for which symbols can provide a aspect of control and of choice.

- what the character eats;

- what the character drinks;

- what the character says;

- where the character puts something;

- when the character does something;

- why something happens...

Each time the story is read the Learner can choose a slightly different version.

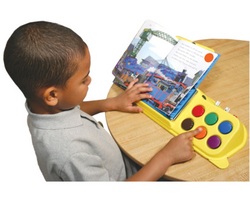

Idea # 15: Give Learner a means to interact with the Reader & the text

It is important that the Learner be provided with a simple means of control such that the Reader is not the one in charge of every aspect of the interaction with the text. This can be as simple as using an AAC system to allow the Learner to make a selection from a 2, 3, or 4 location grid to:

- give commands... “Read that again”, “Act it out”, “Let me see”, "Faster", "Turn page"

- ask questions... “What is that?”, "Why?", "What happens next?", "Who?"

- make comments... “Oh no!”, “that’s cool!” ...

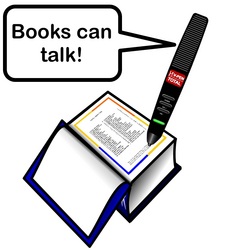

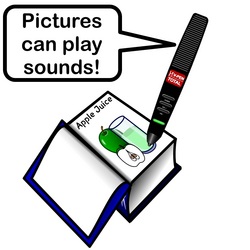

Such interactive communication can also be provided through the use of low tech systems such as the BIGmack or equivalent. The V-Pen and Voice Symbol are also a very effective tools for this task. The Learner may even be provided with a system to choose the person to do the reading!

Idea # 16: Pause for thought

"The right word may be effective, but no word was ever as effective

as a rightly timed pause."

Mark Twain

Pausing occasionally and allowing a Learner the time and space to interact can heighten his/her enjoyment of reading (Justice, L.M., & Kaderavek, J. 2002). It can also promote the development of augmentative communication skills as the Learner attempts to comment on the story so far or to make his/her wishes and thoughts known.

as a rightly timed pause."

Mark Twain

Pausing occasionally and allowing a Learner the time and space to interact can heighten his/her enjoyment of reading (Justice, L.M., & Kaderavek, J. 2002). It can also promote the development of augmentative communication skills as the Learner attempts to comment on the story so far or to make his/her wishes and thoughts known.

Idea # 17: Don't be too controlling

When reading books with children, adults tend to maintain a high level of control (Kaderavek, J. & Sulzby, E. 1998). This can reduce a Learner's enjoyment of the story reading process to such an extent that they are not actively engaged or even dislike the activity. Thus it is important for the adult to give an amount of control over the process to the Learner and ensure that both participants adult and child / Significant Other and Learner play equal roles in the interaction (Rabidoux & MacDonald 2000). Story reading should always be a positive and pleasurable time for the Learner and one in which s/he can exert an equal amount of control over events. Sharing the process will make it more pleasurable for both parties.

"We need to decrease our use of both verbal and non-verbal control strategies. Storytime should be a pleasurable, positive experience for the child, one in which the child is able to exert some control." Kaderavek, J. & Sulzby, E. (2002)

"We need to decrease our use of both verbal and non-verbal control strategies. Storytime should be a pleasurable, positive experience for the child, one in which the child is able to exert some control." Kaderavek, J. & Sulzby, E. (2002)

Idea # 18: Encourage the Learner to predict what will happen next.

Oh dear, that caterpillar has gone and eaten so much food! What do you think is going to happen to him? Do you think he'll go to sleep? Or do you think he'll get a tummy ache? Or do you think he will carry on eating more food? You think he'll eat more food?! Well, let's turn the page and find out ...

If we are providing options to a User of AAC, it would be good to also provide a way of the Learner answering those options indpendently without having to list each in turn and wait for the 'nod'. A set of option cards could be provided from which the Learner could choose, for example. Such cards could be used again and again. The symbols could be used in a number of ways. They could be:

- used directly to allow the Learner to point (or eye point);

- placed on top of BIGmacks to provide voice output;

- produced with Voice Symbol so that they speak when accessed with the V-Pen;

- used on a SGD to provide voice output ...

Idea # 19: Literacy Include Our Needs

"If a lion could talk, we could not understand him."

Ludwig Wittgenstein (Philosophical Investigations, first published in 1953,page 223)

What?! That's crazy! If a lion could speak English then surely we would be able to understand what he was saying. Even if it could only speak lionese, if we had a translator then we would comprehend his message: wouldn't we? Wittgenstein was not specifically talking about lions of course, he could just as easily be talking about dinosaurs or any animal and many humans.

So what did Wittgenstein mean and how does it relate to emergent literacy? Wittgenstein is rather difficult to understand but I take him to mean that if a lion could speak, the language games he would use would be very unfamiliar to us because a lion's experience of the world and a human's experience are alien entities. In order to understand a lion we would have to approach the lion from a lion's perspective. Had we walked a mile in the lion's (metaphorical shoes) then we might begin something resembling a dialogue.

How does this apply to Learners experiencing severe communication difficulties? Well if we approach using just our language and our likes, there might be an issue because Learners with such difficulties may, by definition, have significant problems with language and certainly may not like the same things. We therefore cannot just expect such a Learner to comprehend all that we are saying via the medium of speech alone: we have to approach at the 'lion's level of experience and understanding'. In other words, we have to approach the Learner from the current experience and level of the Learner. That is, we need to be inclusive!

"If children don’t learn the way we teach,

We must strive to teach the way they learn."

Ignacio Estrada

As not everyone enjoys every aspect of the reading experience in the same way. you should tailor your reading activities with the Learner to the Learner's needs, abilities and likes:

"Limit your use of questions with children who do not appear to enjoy being asked questions.

If a child appears more interested in the pictures versus listening to the story,

or if the language demands of the story appear too difficult for the child,

modify the interaction to match the child's interests and skills."

Kaderavek, J. & Sulzby, E. (2002)

Ludwig Wittgenstein (Philosophical Investigations, first published in 1953,page 223)

What?! That's crazy! If a lion could speak English then surely we would be able to understand what he was saying. Even if it could only speak lionese, if we had a translator then we would comprehend his message: wouldn't we? Wittgenstein was not specifically talking about lions of course, he could just as easily be talking about dinosaurs or any animal and many humans.

So what did Wittgenstein mean and how does it relate to emergent literacy? Wittgenstein is rather difficult to understand but I take him to mean that if a lion could speak, the language games he would use would be very unfamiliar to us because a lion's experience of the world and a human's experience are alien entities. In order to understand a lion we would have to approach the lion from a lion's perspective. Had we walked a mile in the lion's (metaphorical shoes) then we might begin something resembling a dialogue.

How does this apply to Learners experiencing severe communication difficulties? Well if we approach using just our language and our likes, there might be an issue because Learners with such difficulties may, by definition, have significant problems with language and certainly may not like the same things. We therefore cannot just expect such a Learner to comprehend all that we are saying via the medium of speech alone: we have to approach at the 'lion's level of experience and understanding'. In other words, we have to approach the Learner from the current experience and level of the Learner. That is, we need to be inclusive!

"If children don’t learn the way we teach,

We must strive to teach the way they learn."

Ignacio Estrada

As not everyone enjoys every aspect of the reading experience in the same way. you should tailor your reading activities with the Learner to the Learner's needs, abilities and likes:

"Limit your use of questions with children who do not appear to enjoy being asked questions.

If a child appears more interested in the pictures versus listening to the story,

or if the language demands of the story appear too difficult for the child,

modify the interaction to match the child's interests and skills."

Kaderavek, J. & Sulzby, E. (2002)

Idea # 20: Guess What!

For those of you who do not know about the genius of Rolf Harris, he used to do a piece of painting on his TV show and, almost as soon as had placed a few brush strokes on the large canvas, he would say 'Can you guess what it is yet?" (which has become something of a catchphrase for him down the years). Guessing, making predictions and anticipating are all important tools in becoming literate. Therefore, we need to assist our Learners to develop these skills and be comfortable in so doing. It would be counter-productive, for example, if we encouraged a Learner to guess and then said something akin to 'Oh, don't be stupid!'

Guessing does not have to involve text initially; in their work on learning to read, Dorothy Jeffree and Margaret Skeffington (1980, Let Me Read, Human Horizons Series, Chapter 2) suggest that drawing simple pictures, and asking Learners to guess what they will be, is a good way of promoting emergent literacy skills. They note that the child with spech difficulties may find making a guess explicit problematic but suggest practical alternatives:

" What about the child who has speech difficulties so that his speech is unintelligible? There is no reason why he shold not play this game - in fact it may help him considerably. But you will have devise a different version for him. As well as the cards which you are going to draw on, you will need a collection of small objects or coloured pictures. When you draw a cat, for instance, he must find a model cat, or point to the coloured picture of a cat, to win." (Jeffree and Skeffinton, 1980, page 39)

In guessing at basic shapes the individual is learning to make sense of linear forms on paper and in developing the concept that lines on paper can represent some 'thing' from the real world. Do not draw abstract concepts or things that are not part of the Learner's everyday experience... you want the Learner to succeed, so it is important to make the task as easy as possible(at least in the beginning).

If the Learner is capable of holding a pencil and putting lines on paper then reverse the process: Let the Learner draw the image and you do the guessing. In this way the Learner is beginning to understand that symbols represent things and can be used in their place, especially when it would be difficult to have the real thing or it is not present.

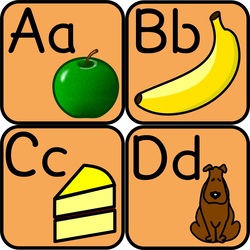

Idea # 21: Assist the Learner to recognise his/her own name

"Evidence also suggests that preschool name-writing ability is predictive of later reading

ability, providing further demonstration that name-writing skills offer an important window

into children’s emergent literacy achievements."

Cabell, S.Q., Justice, L.M., Zucker, T.A., & McGinty, A.S. (2009). Page 55

While many of the Learners with whom you are working may never be physically able to write their own name (although they might be able to do it via a computer system), they certainly should be assisted to recognise their own name. At first, this means we need to devise ways and means of enabling them to recognise their name as a logographic whole rather than by analysis and knowledge of individual letters and sounds. Once that is established, we can use their name as a means of teaching letter sound correspondence and other aspects of emergent literacy.

ability, providing further demonstration that name-writing skills offer an important window

into children’s emergent literacy achievements."

Cabell, S.Q., Justice, L.M., Zucker, T.A., & McGinty, A.S. (2009). Page 55

While many of the Learners with whom you are working may never be physically able to write their own name (although they might be able to do it via a computer system), they certainly should be assisted to recognise their own name. At first, this means we need to devise ways and means of enabling them to recognise their name as a logographic whole rather than by analysis and knowledge of individual letters and sounds. Once that is established, we can use their name as a means of teaching letter sound correspondence and other aspects of emergent literacy.

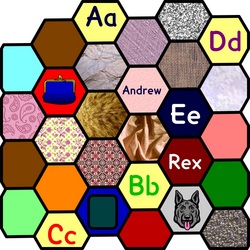

|

One idea for approaching this is to create a set of logos that involve print with which the Learner should already be familiar such as 'Tesco', 'Cadbury', 'Kellog's', etc. Ideally, These should be places or items or events with which the Learner comes into contact almost every day. Into this mix we can add another logo ... the Learner's name. If we have four or five such logos printed on card we can assist the Learner to pick out the one that 'says his/her name'. We can make this easier at first because we can print it in a different colour to the other logos and incorporate the Learner's picture as a part of his/her logo, etc. As the Learner become more successful at this task we can gradually fade the prompts and cues such that the Learner is being given slightly more demanding tasks over time but we are scaffolding the learning experience to assist. When the Learner can pick his or her own name from a set of five all in the same colour, font, and font size then we can use this ability as a platform for further learning. For example, 'with what letter does your name begin?'

Research seems to show that children experiencing a language impairment are not working at a phonological level when recognising or writing their names: |

"It appears that young children are not encoding sounds while writing their names. Rather, they view their names as logograms, unconnected to oral language. Therefore, it is not surprising that in this study, name writing representations did not seem to reflect phonological awareness, but rather children’s print-related skills. Children seem to employ a very different strategy when writing their names than when inventing spellings, which requires at least a rudimentary grasp of the alphabetic principle. The present findings stand in contrast to the assertion that name-writing ability is significantly associated with phonological awareness."

Cabell, S.Q., Justice, L.M., Zucker, T.A., & McGinty, A.S. (2009). Page 59

Cabell, S.Q., Justice, L.M., Zucker, T.A., & McGinty, A.S. (2009). Page 59

This being the case, we should not expect the development of phonological skills as a result of the above idea, rather a recognition of their own name as a logo. However, as already suggested, this skill can be used as a foundation for building other new skills brick by brick. The research did suggest however that there was some correlation between name writing and alphabet knowledge:

"we interpreted our findings to suggest a bidirectional developmental interrelationship between name-writing ability and alphabet knowledge such that children’s knowledge of letters aids in their name writing, and children’s active encoding of letters in the act of writing likely enhances their alphabet knowledge." Cabell, S.Q., Justice, L.M., Zucker, T.A., & McGinty, A.S. (2009). Page 59

However, the Talksense idea above relates only to name recognition and not to the ability to write one's own name. For some (if not many) of the Learner's with whom we work, the ability to write their name, at least by hand, may be problematic for physical if not for cognitive reasons. As such, we have to be careful in assuming alphabet knowledge at this stage. Rather, we should use the skill as a basis for further development. Even when a Learner is able to write some of his/her own name by hand or an alternative methodology such as a computer, it is likely that his/her developmental level will be behind that of a non-language impaired (Typical Language TL) peer:

"The purpose of Study 2 was to compare the name-writing representations of 4-year-old children with language impairment (LI) to those of their TL peers. Results found that the children with TL were significantly more advanced in their name-writing abilities relative to the children with LI" Cabell, S.Q., Justice, L.M., Zucker, T.A., & McGinty, A.S. (2009). Page 61

"we interpreted our findings to suggest a bidirectional developmental interrelationship between name-writing ability and alphabet knowledge such that children’s knowledge of letters aids in their name writing, and children’s active encoding of letters in the act of writing likely enhances their alphabet knowledge." Cabell, S.Q., Justice, L.M., Zucker, T.A., & McGinty, A.S. (2009). Page 59

However, the Talksense idea above relates only to name recognition and not to the ability to write one's own name. For some (if not many) of the Learner's with whom we work, the ability to write their name, at least by hand, may be problematic for physical if not for cognitive reasons. As such, we have to be careful in assuming alphabet knowledge at this stage. Rather, we should use the skill as a basis for further development. Even when a Learner is able to write some of his/her own name by hand or an alternative methodology such as a computer, it is likely that his/her developmental level will be behind that of a non-language impaired (Typical Language TL) peer:

"The purpose of Study 2 was to compare the name-writing representations of 4-year-old children with language impairment (LI) to those of their TL peers. Results found that the children with TL were significantly more advanced in their name-writing abilities relative to the children with LI" Cabell, S.Q., Justice, L.M., Zucker, T.A., & McGinty, A.S. (2009). Page 61

Idea # 22: Bring 'other' word groups to life... give them meaning

While you are reading a story, you can ask the Learner questions about the text.

For example, you might ask if they think that the character is GOOD or BAD, or whether that was a SILLY or SMART thing to do. In this way, we can introduce 'describing words'.

How would we introduce verbs?

What is he doing?

What is she going to do next?

What has it done?

What you do if you were that person?

Prepositions:

Where is it?

Now I can't remember did he put it under the table or in the drawer?

Where shall I put the book? On the shelf? great!

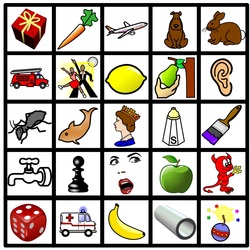

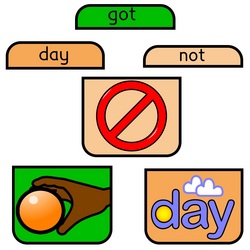

It is a good idea to have Core Vocabulary illustrated as a set of Colour Coded Communication Cards to assist the teaching in this area. These cards can be used time and time again. Please see ideas immeadiately following this for further information.

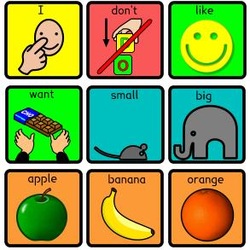

Idea # 23: Produce your own Colour Coded Communication Cards for Literacy Development

It's not diifcut to produce you own symbol cards if you have a software tool such as BoardMaker or Voice Symbol or similar.

1. Decide on the size of symbol cards required.

2. Produce a grid in the software with cells approximately the size you require

3. Fill grid with symbols

4. Save grid

5. Print grid

6. Laminate

7. Cut into individual cards.

The same thing can be done easily with a new piece of software called Voice Symbol. It's advantage is that the paper symbols, thus produced, can speak! When the symbols are touched with a tool called a Voice Pen, the pen reads the cards! It's child's play to do and child's play to use.

NOTE: Colour Coding is detailed in an idea below.

Idea # 24: Produce a second set and cut it up!

There is an additional benefit to producing such symbol cards as a resource with Voice Symbol or Voice Ink. The code (the V-Pen reads the code off the card to produce the sound) covers the entire surface of the symbol including the text. Touching anywhere causes the pen to speak - there is no need for a Learner to be accurate within the card itself. This means that you can cut the text label away from the symbol portion and create a set of resources for symbol/word matching! If the Learner is able to move the pieces so much the better but, if not, the Learner can touch a text label with the pen, listen to the sound and then touch the appropriate symbol section.

Indeed, if the text where to be cut into individual letters, each letter would say the original word when accessed ... that might have an interesting use for spelling that we can explore later! In the illustration below the parts have been mounted using velcro onto a rubber edged carpet (See Idea # 16 below) BUT the text is a little small as there is plenty of room for it to be made larger and clearer (see idea # 18)

When that process is complete, the teacher can show/present the Learner with each text label in a randomised order and ask him/her to decide to which symbol it should be matched. The Learner now has no sound cues and has to work on visual information only. The Learner has to read the word! On completion, the Learner can check his/her own work with the V-Pen to see if s/he has got all the answers correct! We cannot know, from such the small set of labels and symbols, whether the Learner is simply memorising the whole word shape or is actually attempting to figure out the initial letters of the words. However, as word shape relies on visual memory and this will likely become overloaded when more symbols and labels are added, it should be possible to find out!

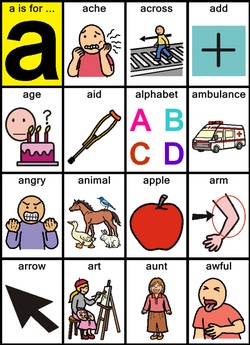

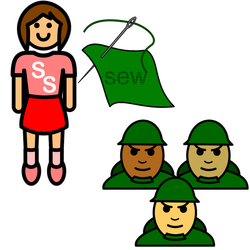

Idea # 25: Colour Code your Communication Cards

Back in 1929, Edith Fitzgerald wrote a book entitled 'Straight Language For Deaf' which, as its name implies, is a manual on a method for teaching language and grammar to those people who have little or no hearing. Although Edith divides sentences up into parts of speech, and has a key system for doing this, at no point in the book does she talk about a colour encoding system (Fitzgerald's original key was based on a set of six symbols with each standing for a particular part of speech). However, such a colour encoding system has been attributed to her and it has become known as the Fitzgerald Colour (colour) coding system. It is a means to classify different parts of speech and to make them easily distinguishable from one another. Though there appears to be no one set colour standard for every part of speech in the system, some colours are consistently used:

adjectives blue

pronouns yellow

nouns orange

verbs green

beyond that there appears to be a variety of colours used in what generally is referred to as a 'modified Fitzgerald key':

adverbials brown

conjunctions white

determiners grey

expletives red

interrogatives purple

negations red

prepositions pink

It should be stressed that you will find all manner of variations on the 'Fitzgerald key' in use although I would recommend a 'standard' as detailed above.

Of course, there may be classes within classes: for example, there are modal and auxiliary verbs as well as lexical verbs. All are colour coded green but a variation in the tone of green used can be made to great effect. Also where nouns are grouped according to categories, each category could have an alternating shade of orange such that neighbouring categories are distinguishable.

Idea # 26: Symbols should have Clear Text Labels

The Learner’s AAC system should contain text. As a rule:

- The symbols should have clear text labels.

- The font, font colour and background colour should all support clarity for the Learner.

- Ideally, there should be a means of reviewing a sentence created from individual

word choices. For example, there should be window which contains the both the

symbol and text as it is built.

Generally speaking, text labels should be above symbols (not below them) as this will maintain a Learner's view of the text as s/he accesses a symbol with a pen or by pointing. The text should be visible to the Learner when the system is in use (therefore font, font size, font colour and background colour are all important as discussed in the symbol section of this website) such that there is every chance that the Learner will begin to associated the symbol with both the written word and the sound.

In the first image above, the text is almost invisible because it is so small. In the second symbol, the text is clearer but it is difficult to tell if it says 'tap' or 'top'. In the last two images, at the bottom, the word tap is more prominent. Decide for yourself which is clearest of the four. The symbol is the same size in each of the four images. The font used, in each case, is the Lexia font which is a free download from the internet. It has been specifically designed to assist disrimination between letters so that it is harder to confuse a 'b' with a 'd', for example.

Idea # 27: Create Communication Carpets as a tool for class use

Such question cards could be individually made, laminated a stored. Each would have a sticky Velcro tab on the rear such that they could be quickly mounted on a Velcro friendly board. Small, rectangular floor mats are ideal for the job because they:

- are Velcro friendly;

- can be purchased locally (bigger supermarkets generally stock them);

- are not expensive;

- usually come with some form of rubber edging that can be punched with a

hole punch to allow mounting to a wall or door if needed;

- can be rolled up and put away when not needed;

- can easily display four quite large symbols and many smaller symbols;

- come in a variety of sizes to suit all symbol purposes;

- are fairly easy to keep clean and maintain;

- non-toxic and safe;

- will work just as well on the floor, on a table top, or wall-mounted;

- are just brilliant for wall displays around the school because the display can be prepared elsewhere, rolled up and then taken to

the site and hung!

|

I recently saw a mat in a store that was divided into four sections with each section being a different colour as a sort of pattern. I didn’t like it at all as a floor mat but I thought that it would make an ideal colour coding carpet for those that need such a thing! It pays to keep your eyes open!

If a sufficiently large carpet/rug was obtained and hung on a wall a whole communication system could be displayed as individual (laminated) symbols which could be readily removed to use as support materials for AAC and Literacy Learning (see illustration below) |

Idea # 28: Create a Word Wall

A Word Wall is a place to display new words to be learnt. The words chosen for the wall are the important core words that the Learner needs to know but are difficult to sound out or difficult for the pupils to learn. New words can be added to the wall each day or each week (depending on the cognitive capacity of the Learner). How many words? Again. it will depend on the cognitive capacity of the Learner: there is no one set 'right' number.

A word wall would therefore not display such vocabulary as bat, cat, and mat but may contain such items as 'every', 'the', 'question', 'would', or 'another'.

A word wall might also be used to teach a particular phoneme blend or other phoneme/letter pattern which a Learner needs to recognise to become fully literate: for example, the use of 'ed', 'ing', etc at the end of certain words as a marker of tense or aspect.

Literacy Symbols together with Communication Carpets (see above and below) make an ideal word wall.

A Word Wall should be USEFUL:

Used... It's not simply a pretty display ... it's a tool for use containing a set of (easy to remove) resources.

Stimulating ... Interesting and motivating for the Learner;

Everyday vocabulary ... Not full of extreme fringe words unlikely to be often encountered. 'Monster' and dinosaur are fringe words!

Friendly ... The Learner should not associate it with Fear or Failure;

Unclear... Unclear in this sense refers to more 'difficult' words for the Learner but, nevertheless, are going to be used;

Large... Easy for the Learner to see: Learners Look at Large Letters! (Therefore not unclear!)

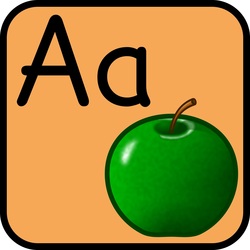

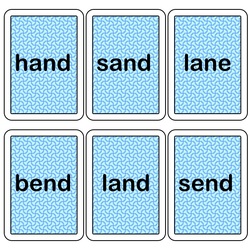

Idea # 29: Literacy Symbols

I have been toying with the idea of a set of symbols for literacy development for some time and have gone as far as designing quite a few: I call them Lit-Syms. A few have already featured on this page.

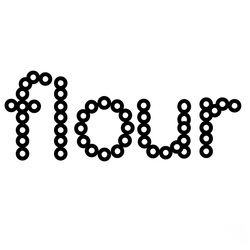

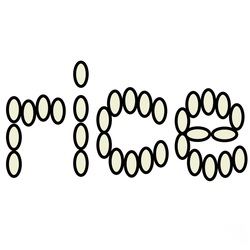

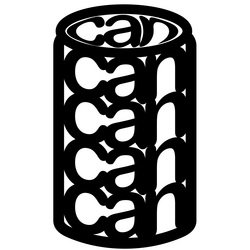

Lit-Syms differ to standard symbols in that the symbol is the word and the word is the symbol! As the Learner looks at the symbol, s/he looks at the word ... it cannot be ignored by the Learner. The idea is that the word itself illustrates its meaning in some way. After a while of using such symbols, the 'symbolic' aspect (as opposed to the text aspect) can be faded, leaving just the word. Lit-Syms would typically be used with Users of AAC to introduce them to literacy by teaching the word with the symbol. Not all words would be illustrated in this way, just Core Vocabulary in the main and any others that were necessary. can all words be illustrated in this way? I believe that they can although some words, that are not 'picture producers' (try illustrating 'could' for example), will take a lot of creativity.

I am not sure if this is a good idea or just another of my crazy schemes! I'd be interested in feedback. Use the form at the bottom of this page for such comments and feedback on the idea. Actually, after a little research on my part, what I thought was original, turned out just to be a reworking of an old technique devised in the late 1960s (by Arnold Miller and his wife: see below) called 'symbol accentuation'. It goes to show, there is probably nothing new under the sun!!