Active Environments

An Active Environment is one in which Learners are 'cognitively engaged' with the curriculum for the majority of the time.

Creating Active N-vironments

An Active Environment is the antithesis of a Passive Environment.

A Passive Environment is one in which individuals acquire 'learned helplessness'.

It should not be assumed that it is a intentionally 'bad' or uncaring set of Significant Others who create a Passive Environment: far from it ... the Significant Others involved can be the most caring, concerned and well-intentioned people you could hope to meet. The environment can be spotless and all can appear extremely efficient and ordered. However, such criteria are not contained within the attributes of the Active Environment (see check list below).

Active Environment: Check list

There is a difference between environments that promote active Learners and environments that promote passive Learners. This difference is nothing to do with the level of caring or the the qualifications of the staff or even the cleanliness of the environment. Indeed, an active environment may,by its very nature, be more untidy than its passive equivalent. It is 'Active Environments' that promote 'Active Learners' and 'Passive Environments' that promote passivity. The latter is very rarely intentional: more often than not, it it an unwanted side-effect of establishments policy, procedure and practice.

In an Active Environment there is evidence of staff encouragement of cognitive engagement of Learners. The list below details some of the attributes of both active and passive environments. If you think of think of things that are missing please contact me and let me know and I will add to the lists below. The more items that can be ticked from any one list the more it is likely that the establishment is either 'active' or 'passive'.

ACTIVECognitively Engagement; Communicative Learners; Language and communication is a focus; Learner Choices; Learners take decisions and staff respond; Learners encouraged to D-I-Y; Learners are given responsibilities; Fly-swatting is avoided; Symbols on Switches; Hold on Help... hang back; Inclusion, involvement, ideas, ... independence and integration; Most Learner time on-task; Learners are motivated (intrinsically amd extrinsically); All Learners working in sessions; Learners know when they are successful; Environment is engineered for learning; Environment is 'Responsive'; Self Stimulatory behaviour is reduced (or eliminated); Staff use open questions; Critical thinking and exploration; Pause on Prompting; Questions (from Learners); Staff use descriptive question types; Timetabling flexibility; Staff expectations are high; Staff expect participation by all; Multi-disciplinary approach; Verifcation of Learner Understanding; Open to change and to challenge; Higher demands on staff |

PASSIVELack of cognitive engagement; Learners are mostly silent; Silence is golden; Functional communication seen as enough; Hobson's choice; Staff take decisions and Learners follow; Learners discouraged to try things for themselves; Learners do not have responsibilities for tasks and chores; Evidence of fly-swatting; Switches and BIGmacks have no symbols or sensory surfaces. Staff are too helpful; they do not allow time for Learners to DIY; Little evidence of a movement towards the three I's; Learners allowed to spend lot of time off task; Learner Queuing Lack of Learner motivation; Learners watching videos or Television during teaching sessions; Little Learner feedback; Environment is supportive of learning; Environment is not 'Responsive'; Self Stimulatory Behaviour is evident and problematic; Staff use closed questions; Rote learning and copying; Lots of intrusive prompting; Lack of Learner questioning; Staff use referential question types; Strict adherence to a timetable; Staff expectations are low; Staff do not ensure participation by all; Staff tend to plan and work in isolation; Unverified assumptions of understanding by Significant Others; Unwillingness to embrace change; Lower demands on staff |

Fly-Swatting

What is flyswatting and what problems arise from it? Let us imagine a situation in a special education establishment: a staff member is moving around a group sitting in a classroom and offering a single BIGmack to each Learner in turn. The Learners are required to activate the BIGmack which then says some message or plays some sound. The staff member makes a comment and then moves away. The BIGmack does not carry a symbol. What do we make of such an activity? What is the Learner actually learning? If we were to ask "and you are doing that because?" What would be the response?

In such situations the Learner is (most likely) presented with BIGmacks throughout the day; maybe an identical BIGmack (same colour) several times. Each time it is presented, the BIGmack says or does something different and, without even a symbol to give some cue as to what is happening, what is the Learner to make of it all (especially if that Learner is experiencing PMLD)? A Learner may learn to 'flyswat' the BIGmack as it is presented and views the staff member's response as a desirable reward to that behaviour. However, such 'flyswatting' activity is viewed entirely differently by the staff member concerned: Staff may assume the Learner's 'co-operation' equates with an understanding of their objective(s) for the session. This may be far from the truth. Of course, some Learners may understand the intent of the session but how do we sort those that do from those that don't as both activate the BIGmack when presented?

Flyswatting is a feature of passivity not activity, or incusion or involvement, although it may be proffered as evidence of such by some staff.

Flyswatting is therefore defined as a conditioned response to a stilmulus with minimum cognitive engagement. The Learner is simply conditioned, over a period of time, to respond in a certain way to the presence of a SGD (Speech Generating Device), switch, communication board and can do so with the very minimum of cognitive engagement. As such, evidence of fly-swatting is an indicator of passivity.

A Learner may have to go through some form of fly-swatting stage in the beginning to interact with any system. However, the difference here is, once the interaction is established, the Learner is tasked to move beyond simply the act of activation and to engage in a task which is cognitively challenging. Consider learning to ride a bike ... at first it is a difficult process but eventually it becomes automatic and we are not conscious of what we need to do to achieve this feat. If we were cycling along a straight road without any obstacles we would not now be cognitively engaged and, like driving a familar route, suddenly realise that we have reached a point on the journey without being conscious of how we got there! Once the task has been mastered therefore and automaticity is acquired, we need to move on to a further objective. It is the cognitive engagement with the new objective that moves the Learner beyond the act of merely fly-swatting.

How can you tell if a Learner is just fly swatting? That is a difficult question to answer. However, if the Learner has been using a particular system for some time (T) which is greater than the time taken to Automaticity (A) then, unless there is cognitive engagement (C), there is a potential for fly-swatting (F):

If T > A & C = 0 then F

The question then becomes, 'How can I tell if the Learner is Cognitively Engaged'?

How can you avoid introducing fly swatting activities? Answer the following questions about the activity:

- Could I achieve a result with my eyes closed? Yes 0 No 1

- Does the action demonstrate a competence beyond that of the action itself? Yes 1 No 0

- Could I continue to get a correct response by accident? Yes 0 No 1

- Is it part of a progressive sequence towards a particular goal? Yes 1 No 0

- Is it a didactic strategy designed to teach awareness of the activity? Yes 1 No 0

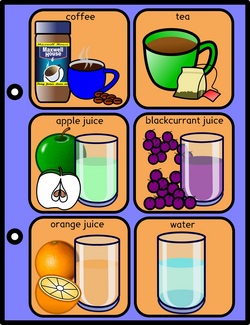

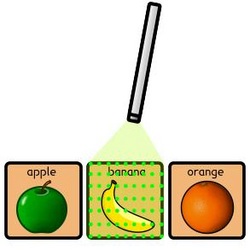

Let us take an actual example and work through the above questions: A child is presented with a communication board at break time and asked to choose a drink. The board has previously been presented many times. It is not just being introduced.

|

The child reaches out and touches the board. A drink has been chosen!

Could I achieve a result with my eyes closed? YES (0) Does it demonstrate a competence? NO (0) Could I get a correct repsonse by accident YES (0) Is it part of a progressive sequence NO (0) Is it part of a didactic strategy NO (0) What is the score tally? Zero! Not a single point has been gained. The nearer the score is to zero, the more likely the activity is fly-swatting. In this situation, anything the child touches provides a correct answer to the staff member's question: there is no possibility of being wrong, especially if all are drinks the Learner likes. The Learner could be responding in a fully cognisant manner, of course, but how would we know? So often, staff assume cognisance rather than testing for understanding. |

Even if the Learner and the board have previously been tested and it has been shown beyond any doubt that the Learner is aware of all the symbols, the activity might still be considered as fly-swatting because, in any educational establishment, the goal should continually be to move beyond what has been learned and to progress the Learner further towards the Three I's. Admittedly, this is a lesser form of fly-swatting than the scenario in which it has NOT been shown that the Learner is fully cognisant of all the symbols on the board.

Cognitive engagement therefore removes an activity from mere fly-swatting. Therefore, we must consider Cognitive Engagement ...

Cognitive engagement therefore removes an activity from mere fly-swatting. Therefore, we must consider Cognitive Engagement ...

Cognitive Engagement

Cognitive Engagement (CE) may be defined as,

'The intentional and purposeful mental processing of session content.'

Cognitive Engagement refers to the thinking skills that a Learner needs to bring into play in order to understand the activity in question and participate successfully.

CE therefore requires strategies that promote:

- inclusion rather than exclusion;

- communication rather than silence;

- manipulation rather than (rote) memorization;

- involvement rather than non-participation;

- exploration rather than immobility;

- challenge rather than automaticity;

- clarity rather than confusion (learning is 'scaffolded');

- structure rather than disorder;

- confidence rather than insecurity;

- arousal rather than boredom;

- safety rather than fear;

as the means through which Learners acquire both knowledge and deeper conceptual insight.

CE can be elevated through a variety of activities such as:

- introducing and exploring the new;

- the inclusion of 'incorrect' responses;

- inducing cognitive dissonance;

- posing 'argumentative' questions requiring the development of a supportable position,

- asking Learners to generate a prediction or rationale during a session.

For further information

go here and here

See also Corno, L, & Mandinach., E.B., (1983), The Role of Cognitive Engagement in Classroom Learning and Motivation, Educational Psychologist, Vol. 18, No. 2, 88—108

It is not practical (and probably not desirable) to have CE every second of the day: there are times when we all need to switch off and 'chill out'. Therefore, there will be planned periods of inactivity ...

'The intentional and purposeful mental processing of session content.'

Cognitive Engagement refers to the thinking skills that a Learner needs to bring into play in order to understand the activity in question and participate successfully.

CE therefore requires strategies that promote:

- inclusion rather than exclusion;

- communication rather than silence;

- manipulation rather than (rote) memorization;

- involvement rather than non-participation;

- exploration rather than immobility;

- challenge rather than automaticity;

- clarity rather than confusion (learning is 'scaffolded');

- structure rather than disorder;

- confidence rather than insecurity;

- arousal rather than boredom;

- safety rather than fear;

as the means through which Learners acquire both knowledge and deeper conceptual insight.

CE can be elevated through a variety of activities such as:

- introducing and exploring the new;

- the inclusion of 'incorrect' responses;

- inducing cognitive dissonance;

- posing 'argumentative' questions requiring the development of a supportable position,

- asking Learners to generate a prediction or rationale during a session.

For further information

go here and here

See also Corno, L, & Mandinach., E.B., (1983), The Role of Cognitive Engagement in Classroom Learning and Motivation, Educational Psychologist, Vol. 18, No. 2, 88—108

It is not practical (and probably not desirable) to have CE every second of the day: there are times when we all need to switch off and 'chill out'. Therefore, there will be planned periods of inactivity ...

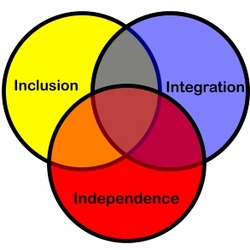

Inclusion, Integration and Independence; The Three I's

As the three R's are reading, Riting, and Rithmetic so the three I's are Inclusion, Integration and Independence. These three areas necessarily go together to form a 'rounded' individual in society.

Independence is the primary goal of the majority of specil education. Other areas, such as communication and mobility, are (probable) factors in the development of independence and, therefore, come under its umbrella.

However, to have independence without integration (into society) leaves a person socially isolated and alone. Also, one can be integrated but not included: I can attend a lecture on astrophysics at Cambridge University. I would be integrated. However, the lecture would (more than likely) go right over my head: I would not be included. Thus, Integration without Inclusion can lead to confusion and a lack of self-worth.

When all three are in balance, the result is a pleasant shade of brown ... a melting pot in which the Learner is integrated, included and sessions are geared towards teaching greater independence.

While full independence is a primary goal, it is a fact that not all Learners will reach it. However, our task is to move Learners ever closer to the goal in order to maximise the benefits that can be gained from life itself. Thus, any step down the route towards independence is a movement in the right direction. Therefore, the task is greater Independence, Integration and Inclusion.

Inactive Periods

A Learner does not need to be cognitivley engaged for 24 hours of every day. There are times when Learners need not be actively engaged ... for example, while:

- resting or asleep;

- watching some TV programmes;

- while 'chilling';

- while listening to music;

There are times that one might not be cognitively engaged in a sensory room, However, it should not be assumed that this is the purpose of a sensory environment! The sensory room's prime purpose is cognitive engagement!

- resting or asleep;

- watching some TV programmes;

- while 'chilling';

- while listening to music;

There are times that one might not be cognitively engaged in a sensory room, However, it should not be assumed that this is the purpose of a sensory environment! The sensory room's prime purpose is cognitive engagement!

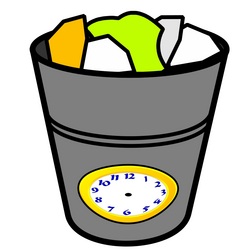

Learner Queuing: The waiting game

Learner queuing refers to the still common practice, in special education classrooms, of rows or circles of Learners waiting their turn as the the focus progressively passes down the line.

In a Learner Queuing system the group of Learners are typically arranged in a row, a semi-cricle or in a circle and an 'activity' is passed around the group one Learner at a time. For example, each member of the group is encouraged to say good morning or interact with a BIGmack as a staff members moves along the line. The last member of the group has to wait until all the others have had their individual turn and the first group member (once the interaction with the activity is complete to the satisfaction of the controlling staff member) has to wait until all others have completed the task and the focus moves back to the group dynamic once again. All group members are on task for a short period of time but play the waiting game for a much longer period of time: the more group members the longer the period of waiting. In a Learner Queuing approach only one Learner is active at any one time:

L1 L2 L3 L4 L5 L6 L7 L8

each Learner becomes active as the focus passes around the group. Even though:

- staff may be very well intentioned;

- and the the activity itself may be worthwhile;

- and very well done...

Learner Queuing is poor practice because of the 'hidden curriculum' aspect; that is, in reality the individuals involved are actually being taught to ... wait. Individual Learners , especially those with special needs, simply cannot spend so much time off task. Some may go to sleep, some may withdraw into themselves, some may focus on other behaviours that they find personally more stimulating (though staff may find such behaviours challenging). Just how much time during a typical day an individual Learner spends waiting is somewhat difficult to ascertain unless there is a time and motion study within the establishement which, by definition, itself affects the outcome (staff may behave differently when they are being observed). If a Learner's IEP has a target that states '<Learner> will learn how to wait appropriately', I am always concerned! It is likely that <Learner> will already be spending a great deal of time waiting!!

The purpose of this website is not just to point out poor practice but to suggest practical alternatives. There are, at least, three possible alternatives to Learner Queuing. These are outlined below. The first is the preferred methodology by Talksense. You may know of others. If you are willing to share alternative methodologies, please get in touch so that I may add other approaches to this section of the C.A.N. page. You may also want to raise issues with the whole of this section. Again, please feel free to get in touch.

Alternative 1: The LAG Approach

The first alternative to Learner Queuing is what may be called the LAG approach where LAG stands for Learner And Group. In this classroom technique a staff member's interactions with a group of Learners (individually) is interspersed with a short whole group activity. Thus, instead of the L1, L2, L3, ... arrangement as seen above, what we now have is:

L1 G L2 G L3 G L4 G L5 G...

L1 G L2 G L3 G L4 G L5 G...

where G = Group

Here, as you can see, the focus passes from Learner to Learner but, in between, there is a short group-based dynamic which maintains cognitive engagement for all participants with the given task. For example, if the session in question was a morning greeting. Learner One would be enabled to say 'good morning' to the group. Following this, and before Learner two was enabled to say 'good morning', the whole group would be enabled/required to say 'good morning' to Learner One. This may be by signing (Makaton, Signalong or other) or through the use of SGDs or some other methodology (indeed, some members of the group may not require AAC). The session dynamic changes: no longer are individual Learners sitting awaiting their turn and, again, waiting after their turn but, rather, only inactive for the time it takes a single Learner to say 'Good Morning' to the group before they are called into action again to respond to each group member's greeting.

Alternative 2: One on One

In the second alternative, individual Learners have one-on-one staff support. The staff member's task is to maintain Learner cognitive engagement while the focus progresses. However, this is easier said than done: how is a staff member to cognitively engage a Learner during a good morning activity, for example, in a meaningful manner while awaiting the Learner's turn and, even if they can do it, how do they do it without disturbing/distracting any other member of the group?

If the Learners are getting on with individual work while the good morning greeting is progressing it is not really true to this alternative but creates a third alternative ...

If the Learners are getting on with individual work while the good morning greeting is progressing it is not really true to this alternative but creates a third alternative ...

Alternative 3: Individual work

In this alternative, Learners are actually working on some activity as a group or as individuals. While they are working, they are interrupted to allow a staff member to present a new focus to them one by one. While the Learners are not waiting, interrupting one period of cognitive engagement with another, only to expect the Learner to return to the first cognitive activity is probably not the best of practices!

However, if the shared activity in question is the use of a group Object Of Reference passed around the group then, as each individual is handed the OOR, s/he moves to the new POLE. Thus, there is no waiting post activity. While each Learner takes it in turn to receive the OOR, they can still be working with their one-on-one staff member until the OOR is presented. Personally, I do not favour this approach to the use of OOR.

However, if the shared activity in question is the use of a group Object Of Reference passed around the group then, as each individual is handed the OOR, s/he moves to the new POLE. Thus, there is no waiting post activity. While each Learner takes it in turn to receive the OOR, they can still be working with their one-on-one staff member until the OOR is presented. Personally, I do not favour this approach to the use of OOR.

What a W.A.S.T.E.

WASTE stands for Without Actively Structured Timed Engagements. It refers to periods in which Learners are sitting idle or waiting such as during Learner Queuing as described above. That is the Learner is spending time outside (Without) periods of cognitive engagement (Actively Structured Timed Engagements). There are many other periods that are WASTED:

- lack of available staff means that the Learner has to wait for assistance;

- materials have not been pre-prepared and so the Learner has to wait while the material

is set up to be used;

- Learner waits while staff assist others;

- Learner waits for his/her 'turn' ...

etc.

While wasted moments may seem unconsequential to staff, they mount into WASTED hours for the Learner during the day. It is during these WASTED moments that the Learner may attempt to self-stimulate or to bring the WASTE to end end by engaging in some form of behaviour that staff find challenging and the individual has come to learn staff will not ignore and is, thus, reinforcing. This may still be reinforcing even if the staff's reaction is to shout at, exclude, or otherwise reprimand the Learner. Talksense would argue that Learners who accept WASTE have simply become passive.

WASTE management takes two forms: Learner WASTE management and staff WASTE Management.

- As has already been stated, a Learner may seek to bring WASTE to an end by self stimulating or engaging in behaviours that staff

may find challenging. Each can be classed as forms of Learner Waste Management.

- Staff WASTE management seeks to prevent Learner Waste Management occuring by eliminating WASTE! That is, staff investigate

how much time Learners are spending waiting and idle and organise activities such that WASTE is significantly reduced or eliminated.

Referential vs Descriptive Questioning

Referential questions:

- are typically answered by a 'reference book' type of memory. Learners learn lists by rote.

- do not necessarily tell you much about the Learners knowledge of a subject, rather, if they have learnt and can recall specific facts.

- are answered using FRINGE words (not everyday vocabulary). Charles Dickens is FRINGE vocabulary.

- are suggestive of passive environments;

Descriptive questions:

- are typically answered using a Learner 's knowledge 'around' a piece of information;

- illustrate a Learner's understooding of a topic;

- can be answered using everyday speech rather than vocabulary that is not commonly used (CORE vs FRINGE);

- are symtomatic of active environments;

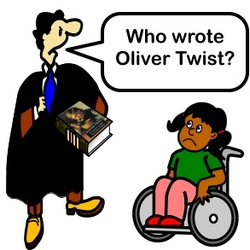

'Who wrote Oliver Twist?' is a referential type question. In order to answer it you need to know that it was 'Charles Dickens' but you do not need to have read the book or know anything about Mr Dickens, when the book was written or what it is about. You could simply memorise the answer to the question. Other referential type questions are:

'What is the name of the 5th planet from the sun?'

'Name a marsupial that lives in Australia?'

'What part of the body is used to pump blood?'

Such questions are beloved by teachers the world over but suggest that rote memory is valued over understanding.

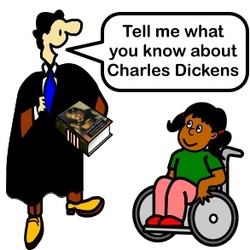

If teachers learn to turn the questions on their heads and ask descriptive type questions that typically might begin with "Tell me what you know about ..."

... Jupiter.

... a Kanagroo.

... the heart

...

then the Learner is challenged to communicate his/her knowledge about the topic and cannot give a single word answer unless the answer is 'nothing!'

To answer a referential type of question using a Speech Generating Device (SGD) requires that the answer has been programmed into the system at some prior point. Programming an SGD with all the potential answers to the millions of questions that could be asked during any school period is a particularly demanding task ... almost never ending and therefore very time consuming. The organisation of such vocabulary forces the addition of hundreds (if not thousands) of extra pages which will be used by the Learner extremely infrequently. The things that we use infrequently are not readily remembered. Thus, the addition of Fringe Vocabulary (such as Charles Dickens) will be used very rarely and then forgotten.

However, if the teacher asks a descriptive type of question then the Learner has a chance of answering using everyday vocabulary from an SGD:

"Tell me what you know about Charles Dickens"

"He was man from old day who write books. One book about boy ..."

Which response ('Charles Dickens' vs 'He was man from old day who write books. One book about boy ...') tells us more about the Learner's understanding of a topic? Which requires more use of language? Which relies less on rote memory? Which uses everyday language? Which does not force the storage of masses of extra vocabulary into an SGD? Which uses vocabulary that is likely to be repeated (used) often throughout a typical day (and therefore remembered)?

Many therapists, teachers and parents spend countless hours storing additional vocabulary into SGDs to cover aspects of the curriculum so that a Learner might be included. However, how often will that vocabulary ever be used/ required? By definition, fringe vocabulary is used rarely. Some fringe vocabulary is used very rarely indeed. However, there are around 1000 words in English that are used very frequently. It would almost be impossible to construct any sentence without using at least one, if not several of them. Therefore, there is no need to program lots of extra pages for specialist vocabulary which wil get used extremely rarely. If staff/significant others were to work with the advancement of a Learner's knowledge and use of Core vocabulary there would be several benefits:

- Less time spent programming new specialist vocabulary;

- More time spent on the teaching of 'language';

- Easier for the pupil/student to learn (there is less to learn);

- Vocabulary is used repeartedly so better recall.

- Repeated use leads to automaticity;

- Greater inclusion for Learner;

- Learner becomes a competent communicator!

- Learner is included in society.

Open Vs Closed Question Forms

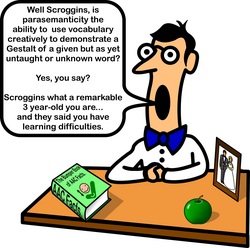

The writers have found culturally deprived children to be strangely indifferent to the content of

verbal utterances while being acutely concerned with the effect that their utterances have on other people. A question that begins with ‘can you tell' - or ‘do you know' is invariably answered ‘yes', often before it is completed. These beginnings are evidently recognized as signals that ‘yes' is the desired answer. Yes-no questions have to be used with great circumspection in the teaching of these children because the children are so adept at and intent upon ‘reading' the teacher's expressions and inflections for clues to the desired response. The children may even succeed in giving correct answers without fully understanding what yes and no mean.

(Bereiter C. & Engelmann S. 1966, p. 37)

Several investigations (Harris D. 1978; Light J., Collier B., & Parnes P. 1985) have demonstrated that speaking partners tend to engage in communicative exchanges that require the learner simply to confirm or deny the vocal mode user’s statements. This strategy speeds up an interaction, but provides the learner with very limited experience in learning to direct an exchange by steering the topic in a new direction. It also limits opportunities to teach symbol combinations that may be part of the graphic mode system. Furthermore, it limits the amount of time the graphic mode user can practice using his or her augmentative system. (Reichle J. 1991 p. 152)

For children who have grown up with answers to questions as their only communication strategy it is difficult to learn to use language in new ways. (Von Tetzchner S. & Martinsen H. 1992)

Multiple factors influence the success of literacy and language learning in the classroom. These influences include ... teacher-student interactions that extend beyond yes/no questioning and encourage students to initiate and sustain interactions. (Erickson K. & Staples A. 1995 p. 4)

A closed question is one that may be answered by either ‘yes’ or ‘no’. An open question is open that requires a response other than ‘yes’ or

‘no’:

CLOSED OPEN

‘Do you want tea?’ ‘What do you want to drink?’

‘Did you watch tv last night?’ ‘What did you watch last night?’

'Did you go shopping at the weekend?' ‘What did you do at the weekend?’

Among users of graphic mode systems, it has been well documented that, when a learner’s partner produces an utterance to which the learner fails to respond, the partner will frequently alter his or her interactional style and ask a series of questions that can be answered ‘yes’ or ‘no’... There is evidence to suggest that many users of augmentative systems tend to match specific classes of communicative opportunities with the response that is the least physically demanding to perform. Second, the learner may lack sufficient vocabulary to provide the flexibility required to generate an answer. When the conversational load begins to fall too heavily on the verbal mode participant, he or she may begin to shorten periods of interaction with the augmentative system user, or even avoid interactions (Reichle J. 1988).

The burden of carrying the interaction cannot be borne inordinately by one member of the dyad. If this happens, the quality, if not the quantity, of the interactions may be jeopardized. (Reichle J. 1991, pp. 150-152)

This section of this webpage deals with the dangers of over-use of the closed question format and offers alternative suggestions. In some instances the ability to provide a yes/no response is a positive step forward and should not be devalued or stopped (see, for example, Keenan J. & Barnhart K. 993). It may be assumed that the closed question format is faster and more effective than its open equivalent but this is not necessarily the case. A 'yes' response does not mean that there is comprehension and the tutor may be fooled into proceeding on this basis. We have all had experience of using 'yes' in response to an uncomprehended situation. For example - you are sitting next to a perfect stranger on a bus. The stranger begins to talk. You do not understand the words. You might say, ‘I am sorry, I did not quite catch that'. The stranger repeats the message. Again, you find the stranger's accent and the message incomprehensible. What do you do? How many people will simply smile and nod their head and try to bluff it. If the stranger smiles at you during this process, everything is assumed to be ok. If the stranger frowns you might change your response. Thus, as in this example, the ‘yes' response does not confirm understanding. You have no idea what is being said!

The closed question format is commonplace in special education establishments. Studies have suggested that classroom talk is dominated by teachers' questions and these are often of the closed type whereas the open question format would have had many advantages (Nuthall G. & Church J. 1973; Blank M., Rose S., & Berlin L. 1978; Redfield D. & Rousseau E. 1981;):

Observations of teacher questions addressed to children of widely different ages and in a variety of disciplines have led to the conclusion that teacher questions are more often of the‘closed' type with known right answers. The responses to such questions by pupils are likely to be terse and simply correct or incorrect. When pupils answer a teacher's questions, they usually say no more and stop talking. Consequently, where such specific, closed questions are frequent, children will say little. ... frequent, specific questions tend to generate relatively silent children and to inhibit any discussion between them. Telling children things, giving an opinion, view, speculation or idea, stimulates more talk, questions and ideas from pupils and generates discussion between them. if all this sounds obvious, then explain why so many studies have found that classroom talk is dominated by teacher questions. (Wood D. 1988 pp. 142 - 143)

Further, people who use AAC systems are asked many more yes or no questions than their vocal peers (Sutton A. 1982; Harris D. 1978; Light J., Collier B., & Parnes P. 1985; Basil C. 1986). For example, adults who interact with users of augmentative systems often over-use yes/no questions. These interactions are problematic for several reasons. First they place the learner in the role of a responder (Light J., Collier B., & Parnes P. 1985). The learner is taught to wait until a specific question is asked before responding. as a result, users of augmentative or alternative systems tend to be poor initiators of interactions (Light et al. 1985). Another adverse consequence of the over-use of yes/no questions is the limited vocabulary it demands. (Reichle J. 1991a)

It may be assumed that there is a 50% chance of being correct when responding to a closed question such as ‘Is Paris the capital of France?' My own experience in this area suggests that, if a person learns to respond to any closed question with ‘yes', s/he will be correct a far greater proportion of the time. Approximately, 90% of the closed questions that people ask require a 'yes' response. That is, when people frame closed questions, the response that is typically required is ‘yes'. Children are eager to please. They soon learn to give the expected response to an adult who is asking them a question. Nodding the head is a very good strategy. It tends to please people. It does not follow, however, that the child understands the question or knows the answer. Be wary!

The closed question is not always faster or more efficient because an assumption of understanding based on a 'yes' or a 'no' response may be misleading. Progression to higher levels of learning should always be based on a knowledge that all the important concepts previously taught have been understood. The closed question format does not guarantee this.

The person responding with a 'yes' or a 'no' answer is not necessary being untruthful. The person may have ‘got hold of the wrong end of the stick'. Consider this example. I hold an empty glass in my hand. I tell you this is an example of the Senojian word 'psarg'. You understand that ‘psarg' is Senojian for 'glass'. I pick up another glass and hold it firmly in my hand. I ask you if this is ‘psarg' and you respond with a nod of the head. I smile. I am pleased you have understood. However, we are both wrong. ‘psarg' means ‘to hold tightly'. You were not trying to mislead me when you gave the positive response. I misled myself.

The closed question format does not encourage the use of an SGD (AAC system). The majority of people with a severe communication impairment have some form of a 'yes' or 'no' response. Thus, there will be no need for them to use an AAC system if all communication interactions are framed as 'yes' or 'no' questions. The closed question format is typically used with people who are passive. It is unclear whether passivity promotes the use of the closed question format or the closed question format promotes passivity. Perhaps the relationship is mutually reinforcing and is a vicious circle.

Open questions should be used whenever possible because they:

- demand an AAC response;

- allow a greater certainty of understanding;

- help promote an active rather than a passive communication style.

The closed question is faster when time is pressing and when we can be positive that a person understands. A person who is already a

proficient AAC user and normally spontaneously requests tea (for example) to drink, would not always need to be asked, ‘What do you want to drink?' but simply ‘Would you like some tea?'

The earlier cartoon reinforces the idea that the use of the yes or no question as a method of checking comprehension is not always valid. It is not always easy to stop using such a communication strategy especially if this has become a habit. The policing of staff use of closed questions is not a recommended solution. That is, a staff member polices other members questions and reprimands them for using the closed format. Rather, we should be helping staff to police themselves. After any interaction with an aided communicator, think about the sort of things that were said and the way in which they were spoken. Did you ask closed questions? What could you have said instead? Recordings of interactions on tape can help this analysis.

There is a game you can play to gain skills in the use of open questions. Get into pairs. One of the pair thinks of an everyday word. The other has to guess the word but may only ask open questions. If a closed question is asked a life is lost. Lose three lives and you are out. Note that a life is always lost when a guess is made (is it a dog?) because the guess is a closed question. Therefore, the maximum number of lives you can afford to lose before making any guess is one (if two lives are already lost, the guess, even if correct would be a yes or no question and

would cause the loss of another life resulting in three strikes and out). The person responding has to answer truthfully but give away as little as possible. If a yes or no question is asked the responder refuses to answer and deducts a life. There are some rules:

- The question ‘What is the name of the thing that you are thinking of?' may not be asked;

- No questions on the spelling of a word;

- The word itself may never be said by the person who has thought of it;

- 'Listing' is prohibited (‘Which of the following is it? An apple or a pear or a plum or a cherry.');

- A question may not be repeated.

Consider the following: Item = apple

Question: Is it an animal?

Response: You have lost your first life!

Question: What sort of thing is it?

Response: It's a plant form, not an animal or a mineral.

Question: What sort of plant form is it?

Response: It is a fruit.

Question: What colour is this fruit typically?

Response: Either green or red or both.

Question: What country does this fruit grow in?

Response: It is grown here, in this country.

At this point, I am not sure if it is a pear, an apple, a plum, a strawberry, rhubarb, or other possibilities. If I guess right, I have won. However, if I guess incorrectly, I have lost because my next guess (even if correct) would be the third yes or no question. I must be careful and narrow

down the range of options. Spelling is against the rules. I cannot ask, 'What letter does it begin with?' for example. What can I ask next?

Question: Where does it have its seeds?

Response: On the inside.

Question: How many seeds does it have?

Response: More than one.

Question: On what sort of plant does this fruit grow?

Response: On a tree.

Question: What sort of ball would the fruit compare to in size?

Response: It is nearer to a tennis ball.

It is now evidenct that is either an apple or a pear. But which? What question can I ask to establish the choice? I cannot ask ‘Which

of the following is it - a pear or an apple?' because that breaks the listing rule. What would you ask next?

Question: What drink can be made from this fruit?

Response: Fruit juice!

Oh dear! I thought I had him! I cannot ask the same question again because it breaks a rule. What should I ask next?

Question: If you were to compare it's shape to something what would it be: a tennis ball or a light bulb?

Response: A tennis ball.

Guess: It is an apple!

Response: Yes (You lost two lives and won.)

It is a difficult game to play because people are not used to asking open questions all the time. It is easy to slip up and ask a yes or no question unintentionally, especially if there is a time limit. Let everybody have a turn as the questioner and then as the responder. Ask for comments afterwards.

The Communication Continuum

There is a communication continuum which is marked by a spontaneous remark at one end:

You are walking through town and the Learner spontaneously says ‘I fancy a cup of tea'

and parroting at the other:

You are walking through town and you wonder if the person with you (the Learner) would like a cup of tea.

You say, ‘Say ‘I want a drink' on your nice machine'.

In between these extremes are two further 'elicited' forms. The first is elicited contextually:

You are walking past McDonald's and the Learner says, ‘I fancy a drink'

The second is elicited via a verbal prompt:

You are walking through town, you turn to the Learner and say, ‘I'm thirsty. What do you fancy to drink?'

Parroting forms the least desirable technique:

Speech is never an end in itself, it is always a means to an end. We use it to convey meaning, purpose and to bring results. To attempt to

teach a child ‘parrot fashion' would be to miss the point (Jeffree D.& McConkey R. 1976)

While parroting forms the least desirable technique within the communication continuum, it should be noted that it is a technique used, in

certain circumstances, by parents (and others) with children. For example, if a child asks for an item and forgets his or her manners parents will say:

‘When you say please.'

Although, initially, the child is told to say the word itself, the direct prompts soon fade:

‘What is the ‘pl' word?'

'Haven't you forgotten to say something?'

‘When you ask properly.'

Eventually, the child may even be completely ignored until s/he asks in a socially acceptable manner. In the Adams Family film, at

meal time, there is the following interchange between Wednesday and Morticia Adams:

Wednesday Adams: ‘May I have the salt?'

Morticia Adams: 'What do we say?'

Wednesday Adams: 'Now !!'

The 'Elicited by a verbal prompt' section can itself be sub-classified into seven categories:

The first is an open ended question:

‘What would you like to do?'

Response - ‘Stop for a drink'

‘What would you like to drink?'

Response - ‘Tea please'

The second is a multi-choice format in which the Learner is active:

‘What would you like to drink: tea, coffee, or a milkshake?'

Response - ‘Milkshake please.'

The third is a variation on the second in which the Learner is still active but Partner/Questioner takes the lead - the alternative:

‘What do you want: tea or coffee?'

Response ‘coffee please.'

Multi choice differs from the alternative option only in the number of choices presented. For a person with severe learning difficulties, a smaller range of choices is more appropriate. The alternative option is a choice of two.

The fourth is a multi choice in which the questioner is active:

‘What do you want to drink? There's tea, coffee, or you could have milkshake. Do you want tea?' (person shakes head)

‘Coffee?' (person shakes head).

‘A milkshake then?' (person nods head)

The fifth is an alternative choice in which the questioner is active:

‘What do you want to drink? There's tea or coffee?

'Do you want tea?' (shakes head).

‘Coffee?' (nods head)

The sixth is a closed question:

‘Do you want coffee?' (nods head)

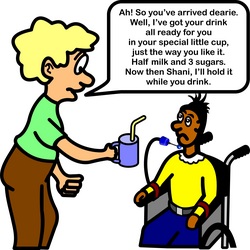

Finally, there is Hobson's choice... No choice at all:

‘I've got you your tea just the way you like it!' (No questions are asked.)

One of the goals of AAC is to give the Learner the skills and the confidence to chat spontaneously. However, if a verbal prompt is required (and initially it is likely that there will be many) then it should begin at the left (as shown on the above table) of the elicited verbal prompt continuum:

‘What would you like to drink?'

If there is no response, it may be repeated...

Gaining eye contact and using the Learner's name - ‘Sam, what would you like to drink?'

If there is still no response, move one step down the continuum. List the options:

‘Well there's tea, there's coffee, there's milkshake, and there's juice. Which would you like?'

(if this is an overload of choice consider the alternative option)

Still no response? Move one step down the continuum:

‘There's tea, coffee, or a milkshake. Would you like tea? Coffee? A milkshake then?'

No response? Oh dear! Then use the closed format:

‘Jenny would you like a chocolate milkshake?'

No response! This is serious:

‘Darn it Jenny, I'll get you a glass of water.'

Note the two strategies used to help promote a Learner response:

- The selective use of a person's name to focus attention;

- Gaining eye contact.

It is unlikely that you will need to move so far down the continuum. However, the option is there should any particular strategy fail. The idea is not to allow the Learner to fail and to provide the maximum amount of choice and opportunity for active communication skills. Of course, this assumes that the Learner knows about drinks and drink names and can say them (has been taught where they are located in the SGD system).

While it is likely that, in the early stages of teaching, much use will be made of elicited verbal prompts, clearly, they should not be the only form of communication strategy used:

... it is therefore important that the communication does not become responsive, i.e. that the individual answers only when spoken to by others or takes the ‘initiative' after being urged to do so. even though it is unintentional on the part of the person who plans the training, the teaching may reinforce a child's dependence. (Von Tetzchner s. & Martinsen H. 1992)

This section above does not make reference to physical prompting. This was intentional. verbal and physical prompts, however, may be used at any point within the communication continuum to help a Learner to achieve a desired response. All prompts should be gradually reduced. Physical prompting and other allied techniques are dealt with separately, in other sections, on this page.

You are walking through town and the Learner spontaneously says ‘I fancy a cup of tea'

and parroting at the other:

You are walking through town and you wonder if the person with you (the Learner) would like a cup of tea.

You say, ‘Say ‘I want a drink' on your nice machine'.

In between these extremes are two further 'elicited' forms. The first is elicited contextually:

You are walking past McDonald's and the Learner says, ‘I fancy a drink'

The second is elicited via a verbal prompt:

You are walking through town, you turn to the Learner and say, ‘I'm thirsty. What do you fancy to drink?'

Parroting forms the least desirable technique:

Speech is never an end in itself, it is always a means to an end. We use it to convey meaning, purpose and to bring results. To attempt to

teach a child ‘parrot fashion' would be to miss the point (Jeffree D.& McConkey R. 1976)

While parroting forms the least desirable technique within the communication continuum, it should be noted that it is a technique used, in

certain circumstances, by parents (and others) with children. For example, if a child asks for an item and forgets his or her manners parents will say:

‘When you say please.'

Although, initially, the child is told to say the word itself, the direct prompts soon fade:

‘What is the ‘pl' word?'

'Haven't you forgotten to say something?'

‘When you ask properly.'

Eventually, the child may even be completely ignored until s/he asks in a socially acceptable manner. In the Adams Family film, at

meal time, there is the following interchange between Wednesday and Morticia Adams:

Wednesday Adams: ‘May I have the salt?'

Morticia Adams: 'What do we say?'

Wednesday Adams: 'Now !!'

The 'Elicited by a verbal prompt' section can itself be sub-classified into seven categories:

The first is an open ended question:

‘What would you like to do?'

Response - ‘Stop for a drink'

‘What would you like to drink?'

Response - ‘Tea please'

The second is a multi-choice format in which the Learner is active:

‘What would you like to drink: tea, coffee, or a milkshake?'

Response - ‘Milkshake please.'

The third is a variation on the second in which the Learner is still active but Partner/Questioner takes the lead - the alternative:

‘What do you want: tea or coffee?'

Response ‘coffee please.'

Multi choice differs from the alternative option only in the number of choices presented. For a person with severe learning difficulties, a smaller range of choices is more appropriate. The alternative option is a choice of two.

The fourth is a multi choice in which the questioner is active:

‘What do you want to drink? There's tea, coffee, or you could have milkshake. Do you want tea?' (person shakes head)

‘Coffee?' (person shakes head).

‘A milkshake then?' (person nods head)

The fifth is an alternative choice in which the questioner is active:

‘What do you want to drink? There's tea or coffee?

'Do you want tea?' (shakes head).

‘Coffee?' (nods head)

The sixth is a closed question:

‘Do you want coffee?' (nods head)

Finally, there is Hobson's choice... No choice at all:

‘I've got you your tea just the way you like it!' (No questions are asked.)

One of the goals of AAC is to give the Learner the skills and the confidence to chat spontaneously. However, if a verbal prompt is required (and initially it is likely that there will be many) then it should begin at the left (as shown on the above table) of the elicited verbal prompt continuum:

‘What would you like to drink?'

If there is no response, it may be repeated...

Gaining eye contact and using the Learner's name - ‘Sam, what would you like to drink?'

If there is still no response, move one step down the continuum. List the options:

‘Well there's tea, there's coffee, there's milkshake, and there's juice. Which would you like?'

(if this is an overload of choice consider the alternative option)

Still no response? Move one step down the continuum:

‘There's tea, coffee, or a milkshake. Would you like tea? Coffee? A milkshake then?'

No response? Oh dear! Then use the closed format:

‘Jenny would you like a chocolate milkshake?'

No response! This is serious:

‘Darn it Jenny, I'll get you a glass of water.'

Note the two strategies used to help promote a Learner response:

- The selective use of a person's name to focus attention;

- Gaining eye contact.

It is unlikely that you will need to move so far down the continuum. However, the option is there should any particular strategy fail. The idea is not to allow the Learner to fail and to provide the maximum amount of choice and opportunity for active communication skills. Of course, this assumes that the Learner knows about drinks and drink names and can say them (has been taught where they are located in the SGD system).

While it is likely that, in the early stages of teaching, much use will be made of elicited verbal prompts, clearly, they should not be the only form of communication strategy used:

... it is therefore important that the communication does not become responsive, i.e. that the individual answers only when spoken to by others or takes the ‘initiative' after being urged to do so. even though it is unintentional on the part of the person who plans the training, the teaching may reinforce a child's dependence. (Von Tetzchner s. & Martinsen H. 1992)

This section above does not make reference to physical prompting. This was intentional. verbal and physical prompts, however, may be used at any point within the communication continuum to help a Learner to achieve a desired response. All prompts should be gradually reduced. Physical prompting and other allied techniques are dealt with separately, in other sections, on this page.

Prompting

Learner prompts are commonplace in special education. They can, however, be over-used and, as such, form part of a passivity-inducing environment. Many prompts are intrusive; such prompts draw the Learner's attention away from the task. Consider a Learner who has been asked to play a piece of music using a switch connected to a BIGmack. After a few seconds, a nearby staff member says, "Come on Timmy... hit that switch.' Apart from being the wrong thing to say (please see the switch skills page ... switch rules), it also serves to draw the Learner's attention (once focussed on the switch) away (now focussed on the staff member). Thus, speaking to a Learner while s/he is on task is likely to draw their attention away from the task and towards you. If the Learner has been (t)asked to do something that is controlled through a BIGmack (or something similar) for example, or through a switch attached to a BIGmack, a number of things have to happen. The Learner has to:

- attend to the request;

- listen to the words in the request and try and make sense of what is being asked;

- figure out a respond to the request;

- send commands to the muscles in his/her body to perform and action ...

For some Learners this may take a little time. If in that period of time, when the Learner is focused on the task, a staff member begins to speak to the Learner, where is the Learner focus moved? It is moved from the task and on to the staff member! The Learner is is now engaged in making sense of a new command! Therefore, we should NOT interrupt a Learner who is focused on a task once the original request has been made unless we believe that the Learner has lost focus. Hence, a period of (at least) ten seconds should be allowed before any prompt is given. Many Learners require even more 'thinking time'.

In addition to the delay before prompting, when prompts are delivered, they should begin with the least invasive or intrusive (unless there is a good reason to begin with the most invasive or intrusive). That means we should begin with a prompt that is specifically designed not take the Learner focus away from the task in hand but, rather, draw specific attention back to it. Such an Increasing Hierarchy prompting mechanism might begin with the staff's use of a laser pen (for Learners who have no problem with vision) moving the point of light around the general area of the BIGmack or switch. Laser pens are ideal for this purpose and are readily available cheaply over the internet from such stockists as Amazon (for example). Some laser pens even can be set to provide a spread of multiple points of coloured light to highlight a surface area. If a Learner would have a problem with seeing laser light(s) then another sensory area must be considered. The question becomes, 'What is going to be the least intrusive for this Learner that will prompt to interaction with the switch?'. Perhaps some form of clicker device could be used from the proximal area of the BIGmack or switch. Excitim produce a L.I.P. switch (which is not a switch controlled by the lips) that is an Learner Interface Prompter. This device attaches to a BIGmack (or similar) and provides a verbal prompt every set number of seconds if a switch is not activated. It is simple to set up and use and is a great alternativee to the use of laser prompting for those with poor visual skills.

- attend to the request;

- listen to the words in the request and try and make sense of what is being asked;

- figure out a respond to the request;

- send commands to the muscles in his/her body to perform and action ...

For some Learners this may take a little time. If in that period of time, when the Learner is focused on the task, a staff member begins to speak to the Learner, where is the Learner focus moved? It is moved from the task and on to the staff member! The Learner is is now engaged in making sense of a new command! Therefore, we should NOT interrupt a Learner who is focused on a task once the original request has been made unless we believe that the Learner has lost focus. Hence, a period of (at least) ten seconds should be allowed before any prompt is given. Many Learners require even more 'thinking time'.

In addition to the delay before prompting, when prompts are delivered, they should begin with the least invasive or intrusive (unless there is a good reason to begin with the most invasive or intrusive). That means we should begin with a prompt that is specifically designed not take the Learner focus away from the task in hand but, rather, draw specific attention back to it. Such an Increasing Hierarchy prompting mechanism might begin with the staff's use of a laser pen (for Learners who have no problem with vision) moving the point of light around the general area of the BIGmack or switch. Laser pens are ideal for this purpose and are readily available cheaply over the internet from such stockists as Amazon (for example). Some laser pens even can be set to provide a spread of multiple points of coloured light to highlight a surface area. If a Learner would have a problem with seeing laser light(s) then another sensory area must be considered. The question becomes, 'What is going to be the least intrusive for this Learner that will prompt to interaction with the switch?'. Perhaps some form of clicker device could be used from the proximal area of the BIGmack or switch. Excitim produce a L.I.P. switch (which is not a switch controlled by the lips) that is an Learner Interface Prompter. This device attaches to a BIGmack (or similar) and provides a verbal prompt every set number of seconds if a switch is not activated. It is simple to set up and use and is a great alternativee to the use of laser prompting for those with poor visual skills.

Increasing and Decreasing Prompt Hierarchies

Prompting is a method of helping Learners in acquiring a skill. Prompts should only be used when necessary and, then, only for a period that is sufficient to assist the Learner. There should always be a plan to phase out all prompts over a period of time otherwise the Learner may become prompt dependent which is yet another feature of passivity. Prompts should only be used after (at the very minimum) a delay of ten seconds to allow the Learner time to process the initial staff request, form, and act upon a response.

An increasing prompt hierarchy is primarily used where a Learner has already learned the basic skills involved in the task. It involves Learner cues that become increasingly more invasive with time until perhaps, finally, the facilitator uses hand-under-hand techniques (see the BIGmack page ISP 22) to guide the Learner to the desired action.

A decreasing prompt hierarchy is primarily used where a Learner has not yet been taught the basic skils involved in the requred task. Thus, it might begin with the most invasive technique and plan to fade all cues and prompts over time. Decreasing Prompt hieracrchies are, therefore, typically used to teach a skill at the beginning of learning something completely new (if necessary) and are quickly faded and removed.

An increasing prompt hierarchy is primarily used where a Learner has already learned the basic skills involved in the task. It involves Learner cues that become increasingly more invasive with time until perhaps, finally, the facilitator uses hand-under-hand techniques (see the BIGmack page ISP 22) to guide the Learner to the desired action.

A decreasing prompt hierarchy is primarily used where a Learner has not yet been taught the basic skils involved in the requred task. Thus, it might begin with the most invasive technique and plan to fade all cues and prompts over time. Decreasing Prompt hieracrchies are, therefore, typically used to teach a skill at the beginning of learning something completely new (if necessary) and are quickly faded and removed.

Passivity and Learned Helplessness

Children enter school as question marks and leave as periods. (Neil Postman)

Passivity is defined as a learned state of dependency on others in an individual regardless of their cognitive and physical potential / ability.

These learners either showed no interest in their environments or were able to participate in the environment without engaging in communicative behaviour. This condition has been referred to as learned helplessness (Reichle J. 1991)

The dependence associated with language learning is related to the degree of passivity and dependence on others found in all groups in need of augmentative communication. People who belong to the expressive language group share the characteristic that, in the majority of situations and especially with regard to self expression, they have been dependent on other people helping them. This antecedent creates habits and ways of adapting to communication that may be difficult to alter when one attempts to give them new means of expressing themselves. (Von Tetzchner S. & Martinsen H. 1992)

The goal of any communication system is to increase an individual's ability to communicate more effectively and efficiently. Typically those who rely on augmentative communication systems communicate at slower rates and with restrictive vocabulary sets. The response

by their speaking communication partners is to dominate the conversation by initiating, setting the topic, asking yes/no questions, not pausing long enough to allow the augmentative communicator to respond and closing the conversation. The augmentative communicator then may assume a very passive role in the conversation with reduced social experiences and reduced motivation to use the communication system. (Morris K. & Newman K. 1993 page 85)

The counsellor's task in the former situation of ‘learned helplessness' is an extremely difficult one. I have to confess that unless such people have a reason to be dissatisfied with a life-long dependent position I have not yet found ways of reducing the threat of a real change on this dimension. Sometimes, however, the dependency is less widespread and areas may be found where they are willing and able to stand on their own two feet. Someone who concedes all conversations to a partner when in company may speak up at work or when responsible for children. (Dalton P. 1994 page 58)

Passivity is commonplace amongst people with a severe communication impairment. In a study by Sweeney (Sweeney L., 1991) 42 out of 50 users of AAC showed some level of learned helplessness when interacting with one or more significant others. The more severe the

communication impairment the greater the degree of helplessness. It would appear that, the development of an individual's ability to communicate also effects an improvement in an individual's desire to act independently. The factors that are involved in creating an atmosphere that is supportive of communication are also the factors that tend to demand more interactive skills of an individual. The relationship is reciprocal: greater communicative ability may lead to greater independence and greater independence may lead to greater

communicative ability. However, prevention is better than cure: the role of communication in the avoidance of personal passivity should be

stressed:

Without an effective means of communication during childhood development of autonomy, exploratory/experiential opportunity, and relative strength of self-image/esteem will be compromised (Sweeney L. 1993)

However well written, structured, or sound a programme of work and study may be, without the right attitude of the people who have to implement the strategies developed, it will be doomed to failure. It is one of the facilitator's primary roles to ensure the correct attitude and understanding of all Significant Others. It is the attitudes, knowledge, understanding, and abilities of Significant Others that will contribute most to the success (or failure) of the cognitive and linguistic development of the Learner. Candappa and Burgess (1989) have shown how the perceptions and attitudes of Significant Others play a primary role in the normalisation of people with a cognitive impairment. They argue:

Our own study, ... strongly suggests that addressing the values and perceptions of carers is one of the primary tasks of normalisation (Candappa M. & Burgess R. 1989)

This is supported by Sweeney (1993):

All children are dependent upon adult caretakers for fulfilment of their physical and emotional needs. In the process of becoming autonomous, children explore and test their world and begin signalling their growing independence to caretakers through physical actions and spoken messages. If provided with an adequate climate for growth, an increasingly solid foundation for independence in adult life will be formed. However, for children with severe communication and/or physical limitations this process of self growth may be overlooked or suppressed. Because many children experiencing the aforementioned challenges are not able to signal their readiness for exploration or independence in traditional ways, parents and other caretakers (e.g. professional service providers, educators, etc.) are inclined to continue to act as direct or indirect agents for fulfilling the child's needs. When later provided with adequate means to express, query, or explore, (e.g. assistive technology) the child may persist in a more passive state due to learned helplessness or learned dependency (Sweeney L. 1993)

For Learners requiring AAC to be successful, they have to have a desire to communicate. The very institutionalisation of some settings may, however, reinforce user passivity. Only when there is a change in institutional practices, reflected through the attitudes of the staff, will any

progress be made. A person for whom all needs are provided (according to a timetable) will find it difficult to put communication to positive use. It may only be through the creation of anomaly, of discord in the daily routine, that the need for communication is created. The normalisation principle may provide just such anomaly and discord creating the desire to communicate in some users (or, at least, allowing those with the responsibility for this process to see the urgency for the development of communication skills). However ...,

To consider the part played by speech in all this. The more a learner controls his own language strategies, and the more he is enabled to think aloud, the more he can take responsibility for formulating explanatory hypotheses and evaluating them. It is not easy to make this possible in a typical lesson: my contention at this point is that pupils are capable of this if they are placed in a social context which supports it (Barnes D. 1976)

Change is not easy. However, it will be made more difficult if the Primary Facilitator lacks belief in the potential of the Learner, the staff, the system and, perhaps, most importantly, belief in him or herself (See Seligman M., 1992). A positive outgoing character, committed to alternative communication and the benefits it can bring, may be more important than the quality of the system being used. Sheer guts and determination coupled with a weaker system will triumph over the best system coupled with indolence and apathy: Programmes aren't paper nor even technology, they are people.

... many adult AAC users may unconsciously choose to be passive. (Merchen M. 1990)

Many users of augmentative communicative systems have learned to refrain from independently engaging in regular daily activities because they have received assistance in virtually every aspect of their life (Reichle J. 1991 p. 151) (See also Seligman M. 1975; Guess D., Benson H., & Siegel-Causey E., 1985)

For children who grow up with motor disorders, the difficulties they experience in moving and speaking and the influence from their environment both contribute to the development of a passive style. These children often place great demands on their parents. Training, feeding and washing take up a lot of time, and there are few activities that the children and their parents can take part in together. Even when the children are small, their parents consider them to be happiest when they are passive. ‘She's as quiet as an angel', and, ‘She is so good', are typical remarks made by mothers about their small children with cerebral palsy (Von Tetzchner S. & Martinsen H. 1992) (See also Shere B. & Kastenbaum R. 1966)

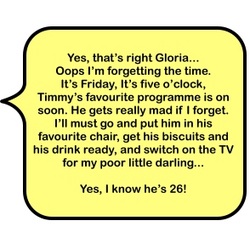

The cartoon makes the point that passive children grow into passive adults. There are many reasons for doing things for children who are

capable of doing them for themselves:

- guilt;

- lack of time;

- wanting to help;

- a belief that a disability equates with inability.

There are also many reasons for the growth of passivity:

- failure to see the long-term consequences of short-term actions (What does it matter if I help a little?);

- the use of closed rather than open questions;

- failure to involve;

- lack of options;

- lack of choice;

- immobility;

- failure to present experience of the world;

- failure to realise that whole sections of standard patterns of language acquisition are being missed;

- failure to check on conceptual development.

The list goes on and on. How are we going to tackle this issue?

A suggestion is to identify a situation in which a Learner is presently inactive and selectively modify it so that the person is gradually empowered. The situation chosen must be non-life threatening. Do not hold back food or drink, for example, until a person is forced to ask for it. One concern is for empowerment through communication skills although other skills come into play.

Take the situation in the above cartoon. What should be modified? How would staff tackle this situation in order to empower Timmy?

First ensure that whatever happens Timmy has a future opportunity to watch his favourite programme. Get a person secretly to video it for him although he should not be allowed to watch it immediately regardless of the outcome because he will simply learn that ‘all things come to he who waits'. Rather, make the viewing of the ‘missed' programme contingent upon future non-passive behaviour (I will return to this later).

Timmy cannot turn on the television himself. However, he would be able to do this with the aid of an environmental control (he may even be able to manage the television's own remote control system). With such a system, he can not only switch it on but turn it off, change channels,

turn the volume up or down, etc. Start by attempting to change only this aspect of the scenario. The functions to control the television are stored into the communicator and he controls the television set through his AACsystem. If it is a low-tech system there are a number of remote control devices on the market that can be operated by a single or dual switch, or with a keyguard by a button.

If empowerment through environmental control is our initial goal then we should not complicate it by trying to do too much too soon. One

thing at a time. Small steps are more likely to succeed. It may be necessary to break this task (task analysis) down into smaller units and work

on a smaller aspect of the task (Turning the television on by hitting a switch for example). Later, we might add an expectation that the user will ask for the environmental control unit and engineer the situation so that it is conveniently out of reach. Too big a step or too many steps taken too hurriedly may be stressful and counterproductive:

For a while, behaving in more assertive ways and being seen by others as having a contribution to make will feel great, If, however, confidence has not been allowed to grow steadily through gradually testing out new possibilities, the person may be too easily thrown by confrontation or unexpected responses. It will feel more comfortable to retreat to the ‘safety' of shyness or self-deprecation. For someone with an acquired impairment to create a new way of being and communicating, time and opportunities for validation will be needed. There is the danger of a return to initial feelings of helplessness and despair if these do not remain available. (Dalton P. 1994 page 71)

What about communication? What do we want Timmy to do? We want him to take command of this situation and do as much for himself as he can and, for the rest, to instruct another. If he has an SGD capable of performing remote control this is a good starting point. Alternately, any remote control system that he is able to operate is as good. As an additional strategy (or the only strategy if remote control is unavailable) Timmy should be provided with the vocabulary necessary for him to ask for the television to be turned on. However, all his life the television has been turned on for him. If this no longer happens what might his reaction be? Do not expect the task to be easy. Timmy is unlikely to change the acquired habits of a lifetime overnight. Prevention is better than cure but Timmy has already caught the bug.

If the expectation is that Timmy will ask for the television to be turned on he must have access to the necessary vocabulary. It may be a phrase (‘Mum, will you turn on the TV please?') or a word or set of words (‘television', ‘programme', ‘Star Trek', ‘watch', ‘on', etc). Timmy must understand this vocabulary and the concepts involved. It should not be simply assumed that he does, it should be checked. Having checked his understanding of the words or phrases, he must be taught where the vocabulary is positioned on his system. Role play will give him chance to practice vocabulary and gain skills in its use. We might make a contract with Timmy such that, from next Monday, if he wants the television on, all he has to do is say the word television and it will be turned on. He may need verbal prompts initially and there may be some screams but, if he has understood and agreed and we are creative, it will work. It is important that we specify what verbal behaviours he must exhibit in order to gain the reward. A list of acceptable words (‘television',‘Star Trek', ‘watch') should be made. If he uses other words a creative response is all that is needed:

‘Sorry I'm not sure what you want. Think of another way to tell me.'

What if he doesn't do what we want? If, after a time, the television is turned on anyway he will learn that waiting achieves the desired goal. There must be contingency plans to address problems that may occur. However, if we have:

- checked that he understands the concepts involved;

- taught him the required vocabulary;

- created opportunities in which the vocabulary can be used;

- told him that, in future, he will have to ask for the television to be turned on;

- provided opportunities for practice;

- verbally prompted him to do so.

How can he fail?

Suppose Timmy is not able to contract with us or refuses to do so? The scenario is the same. Check the concepts; teach the vocabulary; role

play for experience; repeat the experience with verbal prompting and (if necessary) physically cuing; reduce the prompting and cueing; target the event and go for it! What if it fails? Be positive! However, there should always be a contingency plan.

We should anticipate and cater for the fact that even the best laid plans go wrong. Timmy must not be allowed to fail and his experience should be positive and rewarding. What can go wrong?

A) Timmy does nothing. He just sits and waits.

B) He says the wrong words.

C) He just points to the television instead of using his AAC system.

D) He screams and points to the television instead of using his AAC system.

E) He screams and screams.

F) He screams so much he has a seizure

G) He begins to scream and pound the AAC system. His reaction becomes increasingly more violent.

H) He begins to bite himself.

It is essential that we make a list of all that may happen. The Significant Others involved can brain-storm the possibilities. Of course, it is possible that he does something that has not been considered. In which case, we need to think fast. The rule should be ‘No one fails'. It may be necessary to modify the original objective but, at the very least, there has been success in part and there can be progression from this point.