Good Practice in the Care of People Of Disability Who are Bed Bound.

July 2021

This page details good practice in the care of People Of Disability who are bed-ridden (temporarily or permanently) for any reason. It is relevant to all those people (professional or amateur), who perform some type of caring service on behalf of persons of disability (nurses, carers, therapists, support workers, assistants, parents, husbands, wives, family members, friends, volunteers, or any other person I have omitted in this list). It may even hold some relevance to those working in special education, particularly residential special education. This page details observations of my experience as a newly disabled person both in hospital and at home following my discharge from hospital. I also think that it might be relevant to other POD especially IRON POD (continue reading for an explanation of those two words). If that applies to you, please contact me and let me know what you think.

I kept copious notes throughout my first year. This page is the result. If you would like to comment on any aspect of this web page, there is a form situated at the bottom of this page for this purpose. This page is dynamic, not static, in that I am continually adding to it as new issues arise or there are further developments in existing points made. To indicate any new additions, I will include a date and, if an update, the word 'update'.

|

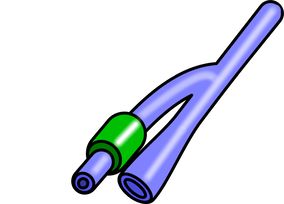

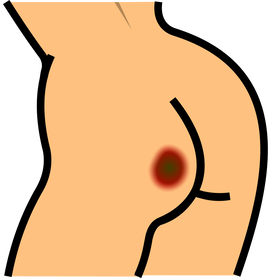

I am a disabled man in my late sixties. A year ago, in August 2020, I had a major stroke that put me in Kings Mill Hospital for several weeks. The stroke left me with a left hemiplegia, paralysed completely down the left-hand side of my body and very weak core muscle strength. It also meant that I was doubly incontinent and was fitted with a catheter. Full-time catheterisation meant that I was prone to bladder infections (which are not pleasant). It seemed that I was on a permanent prescription for bladder and urinary tract infections and the antibiotics added to the volume of pills and potions that I had to swallow every day. The problem is that, following the stroke, I found swallowing difficult and would often choke when eating or drinking.

|

Thus, I had to have all my drinks thickened and avoid certain foods. The stroke also affected my speech and talking became something of an effort. Indeed, if I am emotional, or in pain, or my throat is dry, or I am not feeling well, or for reasons unknown, I cannot speak at all and have to resort to using Makaton sign language or my V-Pen and board (more on communication later on this page). As if not all that was enough, I found myself having to cope with lengthy periods of pain and poor post-hospital provision. All of this was during the Covid lock-down, which further compounded my nightmare. Having a stroke made me feel like Gregor Samsa, the salesperson in Franz Kafka’s surreal book (‘The Metamorphosis’: Die Verwandlung. Original in German, 1915), awakening one morning, only to discover that he had inextricably transformed overnight into a very different, somewhat repulsive, being. I awoke, knowing I would have to learn to deal with a new reality; one in which many people might view and treat me differently from now on.

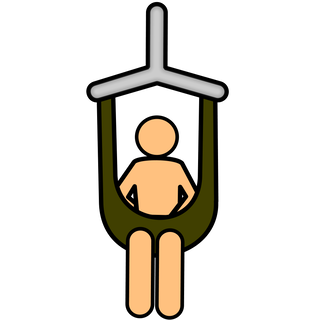

On leaving hospital, I was provided with a manual wheelchair, a hospital style bed, a mobile hoist and sling, a commode (which I have never been able to use for its intended purpose), and a very poor quality over-the-bed style table that I used for just a few days before purchasing a much better version from Amazon. An interim care package with A.M.G. was set up for me that involved four calls during a day but this provision only lasted for a short time until circumstances forced my wife to set up our own system of care. Such service provision was quite difficult to set up and proved to be frighteningly expensive. Having worked all my life and saved for retirement, no financial assistance for support was available; my retirement savings had to be used to cover all the cost of care. Yet, if I did not bother to plan for retirement, and had no savings, then the cost of care would have been virtually covered and the service almost free. My wife is planning on giving up work to help with my care very soon (Visser-Meily, Post et al 2009; Cameron, Cheung et al 2011; Cameron, Stewart et al 2014; Bastawrous, Gignac, et al 2015). She cannot cope with a job and having to meet my needs during the evening and the night. We applied for an Attendance Allowance; to offset some of the income we were losing, only to find that on the maximum level to which we were entitled is £89 per week. Further, my wife is entitled to a Carer’s Allowance of approximately £60 per week. These allowances, plus my state pension, barely cover the cost of the level of care (Rajsic, Gothe et al 2019) that I now need on a daily basis. However, I am truly grateful for the help that I received. I am aware that, in other countries, I would not be provided with anything at all and would have to pay for every little bit of support. I thank the gods that I was born in the UK. We finally settled with a Care Company called Green Square Accord who appeared to meet our needs.

All my working life, I was involved, in one way or another, with People Of Disability (POD) and or learning difficulties. I also was involved in the provision of training for professionals and support workers. I worked alongside gifted Speech and Language Therapists, Occupational Therapists, and Physiotherapists as well as many talented teachers and support staff in many different countries. The focus of the training I provided concerned good practice in education and support provision for staff working with individuals experiencing special needs. It now seems somewhat ironic that I am in need of that support myself! The irony is not lost on me. I had become an I.R.O.N. (Individual totally Reliant on Others for Needs) P.O.D. (Person Of Disability). In POD, the Person comes before the disability but the use of 'of' suggests that the disability defines the Person. Still, the Person comes first, the disability second. I am a POD. What type of POD am I? I am an IRON POD. In IRON the Individual comes first. The Reliance upon Others follows. Needs comes last but defines the Individual, an Individual with needs. The needs are supplied by Others. Thus, putting it all together, it assembles as IRON POD.

|

The level of care provision both in hospital and in post-hospital settings varies wildly from the incredibly good to the unbelievably poor and, as an IRON POD, I thought that I should put down in print my experience and thoughts on the care I have received. What would I consider best practice? (MacKenzie, Creaser et al 2017) I should have some insight, after almost a year of daily care and a little, rather inadequate, post-hospital provision. When a person is ill, the last thing about which they should be worried is the level and standard of care provided. However, the realisation soon comes that, for Individuals totally Reliant on Others for their Needs (IRONs), the standard of care provided plays a major role in an individual’s quality of life (Mayo, Wood-Dauphinee et al 2002; Opara & Jaracz 2010; Van Mierlo, Van Heugten, et al 2016; Caro, Mendes et al 2017)

|

As an IRON POD, I soon came to realise that my future was forever changed. I would, short of some miracle, always be totally reliant on the kindness of others and, if that kindness was, for some reason, to fade and the others chose to walk away, I would be helpless, trapped inside my own body: an IRON POD, a prisoner in virtual irons created as the outcome of a stroke. I understand why so many, in my position, become depressed and even suicidal (Parikh, Eden et al 1989; Parikh, Robinson et al 1990; Van de Weg, Kuik, et al 1999; Kneebone, & Dunmore 2000; Pohjasvaara, Vataja et al 2001; Berg, Palomaki et al 2003; Cassidy, O'Connor, & O'Keane 2004; Niedermaier, Bohrer et al 2004; Suh, Kim et al 2005; Mitchell, Teri et al 2008; Hadidi, N., Treat-Jacobson, D.J., & Lindquist, R. 2009; De Man‐van Ginkel, Gooskens et al 2010; Srivastava, Taly et al 2010; Cameron, Cheung et al 2011; Herrmann, Seitz, et al 2011; Schmid, Kroenke et al 2011; Salter, McClure et al 2012; de Man-van Ginkel, Hafsteinsdóttir et al 2013; Broomfield, Quinn, et al 2014; Mitchell, Sheth et al 2017; Sarfo, Jenkins et al 2017; Towfighi, Ovbiagele et al 2017; Das & Rajanikant 2018). Life without hope is not life at all. If post-stroke provision is poor, it is easy to lose hope because, the little support given, gradually starts to fade away, the individual is left alone, waiting for something of significance to occur, and constantly experiencing setbacks that only lead to further periods of waiting. I am currently waiting for an alternative to my catheter (waiting three months already) with which I have an ongoing problem, waiting for an electric wheelchair assessment (waiting over a month so far and almost a year post-stroke), and waiting for my virus inoculation (why, when all my able-bodied friends have been inoculated already, am I still waiting?). If the wheelchair assessment finds me competent, I, no doubt, will have another long wait to learn, and to get, what I am entitled. Do I want special treatment? No. Am I deserving of more attention because of my stroke? No, I realise I am not special but I would like just a little more understanding of my predicament. Having no electric wheelchair virtually ensures that, without the help of others, I must spend day after day in the same position, in the same bed, in the same room. Others come to see me and typically talk of the weather outside, such conversations only serving to reinforce my feeling of being shackled, unable to escape. Not that I complain about the topic of conversation, I do not want to risk visitors electing to refrain from communication with me. I am still able to laugh at my situation and the events that happen. If I could not, I think that I would go quite mad! C’est la vie, n’est-ce pas? When I feel low, I try to take my mind to a different place. I might start writing a little more of this paper, for example!

Update (some weeks later than the above paragraph):- I now have had my virus inoculations, my catheter assessment (I still need a catheter. I was in terrible pain all the time that I was without a catheter and it had to be replaced.), and the first part of an electric wheelchair assessment (I will be provided with one for which I am really grateful). I now await the second part of the assessment (an outdoor road safety assessment) that I can request when I feel confident in the wheelchair's use. Why wasn't all of this explained to me much earlier after the stroke? It would have improved the quality of my existence in the early months post-stroke when my depression was at its most intense. The requirement for better post-stroke provision is becoming clear to me. I hope that this paper will help to make it clear to others (specifically, those in a position to make things happen) too.

Update (some weeks later than the above paragraph):- I now have had my virus inoculations, my catheter assessment (I still need a catheter. I was in terrible pain all the time that I was without a catheter and it had to be replaced.), and the first part of an electric wheelchair assessment (I will be provided with one for which I am really grateful). I now await the second part of the assessment (an outdoor road safety assessment) that I can request when I feel confident in the wheelchair's use. Why wasn't all of this explained to me much earlier after the stroke? It would have improved the quality of my existence in the early months post-stroke when my depression was at its most intense. The requirement for better post-stroke provision is becoming clear to me. I hope that this paper will help to make it clear to others (specifically, those in a position to make things happen) too.

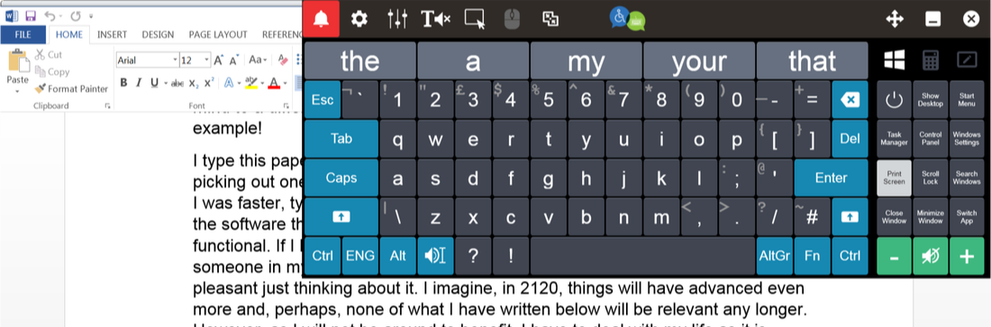

I type this paper using an on-screen keyboard called Click2Speak (it is very good and it is free)(illustrated below) and, currently, I am using an on-screen keyboard I built myself using The Grid 3 software from SmartBox (which is fantastic), controlled via a wireless trackball, picking out one letter at a time. Click2Speak was not as fast as I would have liked and it didn't have many of the features that I wanted. Having said that, Click2Speak is still very, very good. The Grid 3, however, in my opinion, is the best on-screen keyboard software currently available but it is not free (although, I think that it is worth every penny). Prior to the stroke, I was faster, typing with two able hands. I am grateful for both the technology and the software that enables me to type, while in bed, with half of my body not functional. If I have to be disabled, I am glad it is in 2020 and not in 1920! Life, for someone in my position, must have been terribly difficult a century ago. It is not pleasant just thinking about it. I imagine, in 2120, things will have advanced even more and, perhaps, none of what I have written below will be relevant any longer. However, as I will not be around to benefit, I have to deal with my life as it is today. ‘Helper robots’, programmed to meet my every need, only exist in fiction. Until they become reality, people must fulfil that function for, at least, a small part of my day. During the night, my wife was, and still is, ‘on call’ to provide my care, even at three in the morning, although she has to work during the daylight hours and needs to sleep well to be able to function. When she had a daytime job (she was a teacher), I would lay in my bed, often in some pain, during the night, trying not to call her, so as not to disturb her sleep to come and help me. However, after a while, sometimes, I could not stand being in pain any longer and simply had to wake her. This remains the situation today and I do not see it changing significantly in the near future. I have a button, by my bed, downstairs that rings a bell upstairs in the bedroom. One particularly bad night, I had to summon her three times. I feel awful doing it once during the night; imagine how I felt having to do it three times. Typically, each ‘call’ keeps my wife fully occupied for around thirty minutes and so, she loses approximately forty minutes of sleep each time I have to awaken her. I am usually awake throughout the night. My doctor prescribed medication to help me sleep but it did not work. Apparently, a doctor may not prescribe anything stronger or more effective. Such a thing must exist because they put Patients to sleep in seconds to perform surgery. As I do not sleep at night, I tend to fall asleep during the day for short ‘naps’ of perhaps an hour or two. I have fallen asleep while holding a drink in my good hand with obvious consequences! A very wet bed and more work for those having to care for me. I try not to sleep at all during the day such that I have a better chance of sleeping at night. However, my body has a will of its own and it is often stronger than my will to remain awake.

The experience I had in hospital after my stroke was not a good one overall. I scribbled notes in a jotter, throughout my stay, in rather poor quality handwriting; it is hard to write with just one hand while lying in bed with a notebook resting on the blanket, perched precariously on my remaining good raised knee. In reviewing my notes, on one page I had written, ‘I hate it here’ and on another, ‘some nurses nice, some nurses mean’. I particularly found some of the night staff I encountered to be ‘mean’. It seemed like they resented having to help me. Perhaps, having to work throughout the night is a chore and staff resent it. I can empathise with that but it is no reason to treat Patients any differently. I grew accustomed to long waits of fifteen minutes or more after pressing the nurse call button. I am aware that nursing is a busy and demanding occupation. I have nothing but respect for the job that nurses do and believe they deserve a significant pay rise to reward their dedication. However, a few are not deserving of such recognition. One night, after waiting for nearly twenty minutes for someone to answer my call, a nurse finally came to my bedside, she switched off the call light, which was flashing on the wall by my bed, and then walked away without saying or doing anything at all to or for me. My wife wrote to the Patient Experience Team to raise this issue but things did not improve. Another time, I was in a bed with a faulty bed control. It was night and the lights were out. I was very uncomfortable but could do nothing to help myself except to try to use the bed control to reposition my body a little. In the poor light, I hit the ‘raise bed’ function thinking that I was raising the top of the bed just to sit up. When I realised that I had raised the whole bed by mistake. I tried to lower it but that particular function was faulty and not working on my control, so the bed remained raised in its highest position. A while later, a night duty nurse, on seeing my elevated position, came up to me and started to scold me like a little child. I tried to explain but my speech was bad following the stroke and I struggled to speak. The nurse made no effort to listen and comprehend my poor communication and continued to berate me. He used the separate bed control at the foot of the bed to lower the bed. He told me that I should go to sleep and stop messing with the bed control as it was not safe to be

“way up in the air.”

He then took my bed control and positioned it behind me such that I could not reach it and had to spend the remaining part of the night without any control over my position whatsoever. He said that he would be in trouble if I were to fall out of bed so high up (where was the concern for me?). Fall out? I could not even roll over on my own let alone fall out of bed. The side railings were in use and in the up position! How could I possibly fall out of bed even if the bed was atop a mountain? That particular nurse showed no understanding of my condition or my predicament. I was just a ‘naughty child’ messing with the bed control in his mind. On yet another night, I had been moved from the main stroke ward to an individual room, for a reason that I do not remember, and I really was really in need of a drink. I was so dry. I pressed the nurse call button and waited. Twenty minutes later (I got into the habit of timing my ‘waits’), I heard nurses talking outside my room;

“Who’s buzzing?” “Oh, it’s just the man in room x. He can wait.”

I waited another fifteen minutes before I got a drink. It got so that I dreaded the night. I was not sleeping well and would lie awake becoming more uncomfortable because I was unable to adjust my position sufficiently. It is unnatural to remain in the same position for long in bed, recordings of sleep patterns show regular body movement throughout the night (https://www.23andme.com/en-gb/topics/wellness/sleep-movement/). I lay awake for hours, much of the time, trying to move my body a little, using a combination of the bed control and my one good leg, to make myself more comfortable and ease the increasing pain, particularly in my bottom. I lay, waiting for the daybreak when, just before breakfast, nurses would arrive to wash me and make me comfortable, ready for the day to come. Time passes slowly when there is little to do to occupy the mind. I was very reluctant to use the nurse call button because my previous experiences were less than positive. I would lie, in some degree of discomfort, longing for someone who would come and help me. Some nurses were fantastic and nothing seemed too much trouble for them. One nurse sat by my bedside one day when I was feeling particularly low. She took the time to talk to me and tell me of other people she had met who had a stroke like mine and made an amazing recovery. She even held my hand. She was positive and caring. I wish all nurses were like her.

“way up in the air.”

He then took my bed control and positioned it behind me such that I could not reach it and had to spend the remaining part of the night without any control over my position whatsoever. He said that he would be in trouble if I were to fall out of bed so high up (where was the concern for me?). Fall out? I could not even roll over on my own let alone fall out of bed. The side railings were in use and in the up position! How could I possibly fall out of bed even if the bed was atop a mountain? That particular nurse showed no understanding of my condition or my predicament. I was just a ‘naughty child’ messing with the bed control in his mind. On yet another night, I had been moved from the main stroke ward to an individual room, for a reason that I do not remember, and I really was really in need of a drink. I was so dry. I pressed the nurse call button and waited. Twenty minutes later (I got into the habit of timing my ‘waits’), I heard nurses talking outside my room;

“Who’s buzzing?” “Oh, it’s just the man in room x. He can wait.”

I waited another fifteen minutes before I got a drink. It got so that I dreaded the night. I was not sleeping well and would lie awake becoming more uncomfortable because I was unable to adjust my position sufficiently. It is unnatural to remain in the same position for long in bed, recordings of sleep patterns show regular body movement throughout the night (https://www.23andme.com/en-gb/topics/wellness/sleep-movement/). I lay awake for hours, much of the time, trying to move my body a little, using a combination of the bed control and my one good leg, to make myself more comfortable and ease the increasing pain, particularly in my bottom. I lay, waiting for the daybreak when, just before breakfast, nurses would arrive to wash me and make me comfortable, ready for the day to come. Time passes slowly when there is little to do to occupy the mind. I was very reluctant to use the nurse call button because my previous experiences were less than positive. I would lie, in some degree of discomfort, longing for someone who would come and help me. Some nurses were fantastic and nothing seemed too much trouble for them. One nurse sat by my bedside one day when I was feeling particularly low. She took the time to talk to me and tell me of other people she had met who had a stroke like mine and made an amazing recovery. She even held my hand. She was positive and caring. I wish all nurses were like her.

I started to believe that hospital is the worst place to be when ill. My hospital was charging £10 per day just to watch TV. I refused to pay such an exorbitant amount and, as listening to the radio was free (when it was working), I would do that instead. My wife came to see me every day. How I looked forward to her visits. I asked her to buy me a DVD player and to scour the local charity shops and purchase any films on disc she found that she thought I might like. Doing all of that was much less expensive than paying for the ‘privilege’ of watching hospital TV. I passed the long days and nights watching film after film, even though I had seen most of the films before. I longed to go home from hospital so that I could recover. It would be weeks before my wish came true and then a completely new set of issues with post-hospital provision and care teams would arise. Do staff receive training in basic Patient / Client care? If they do, some attending must be sleeping throughout the course or the course is not fit for purpose. My experiences prompted me to write this paper to give those in a caring or administrative role a basic guide to good practice written by someone with first hand and current experience of care / Patient provision; an insider’s view.

I wish to make it clear that, although this page may read like a criticism of Carers and Nurses, it would be mistaken to conclude I have a negative opinion of people working as either Carers or Nurses. Far from it! I have encountered many outstanding Carers and Nurses. I believe both deserve a higher status for the essential function they play in society. Where would I be without them? In a very bad situation without doubt. However, no matter how good a Carer/Nurse is, there is always some room for improvement. Client feedback is therefore important (Tasa, Baker, & Murray 1996; Vingerhoets, & Grol 2003; Bastemeijer, Boosman et al 2019; Berger, Saut, & Berssaneti 2020). As feedback, I hope this paper helps.

Below are sixty something points I have noted/experienced as an IRON POD confined mostly to bed and with knowledge gained through my earlier work (as a TAB – Temporarily Able Bodied person) in supporting special needs across the world over many years. The points made are grouped together under subheading categories. These are not in any particular order of importance. Some points deal specifically with my time spent in hospital and relate to the nursing provision. Others relate specifically to post-hospital care provided at home. Most are equally relevant to both forms of provision. I use the term ‘Client’ throughout this text to refer to the person in need of assistance. A ‘Client’ may be called a service user, a customer, a Patient, or some other term of reference, depending upon your specific area of provision. ‘Carer’ is used throughout to denote the provider of care be it a qualified nurse or a person working in a caring role for a care provision company. I use the term ‘Patient’ if the experience directly relates to my time in hospital although the point made might equally relate to both areas of provision. 'Significant Other' is used to describe any person identified as significant who interacts with and / or enables a Client. This will include a spouse, partner or other family member, friend, and any person who is likely to have more than a passing interest in the Client and with whom the Client may attempt to communicate, in any way, on a reasonably frequent basis.The acronym POD is used to represent a Person Of Disability or People Of Disability depending on context. The acronym IRON is also used frequently throughout this page. Its meaning was detailed earlier on this page.

This page is divided into seven sections, each dealing with a specific aspect of my new experience as an IRON POD.

a) The goal is Control (Follows immediately)

b) Communication (Starts just after point 8)

c) Client Care and Care Practice (Starts just before point 17)

d) Choice is a Voice (Starts just before point 56)

e) Eating and Drinking (Starts just before point 59)

f) Consultation and Coordination (Post-Stroke Provision) (Starts just before point 61)

g) Bibliography and References (Starts after point 65)

The first of these is: -

This page is divided into seven sections, each dealing with a specific aspect of my new experience as an IRON POD.

a) The goal is Control (Follows immediately)

b) Communication (Starts just after point 8)

c) Client Care and Care Practice (Starts just before point 17)

d) Choice is a Voice (Starts just before point 56)

e) Eating and Drinking (Starts just before point 59)

f) Consultation and Coordination (Post-Stroke Provision) (Starts just before point 61)

g) Bibliography and References (Starts after point 65)

The first of these is: -

The Goal Is Control / Control is the Goal.

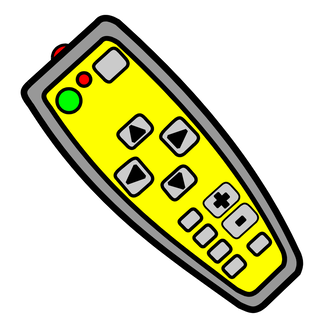

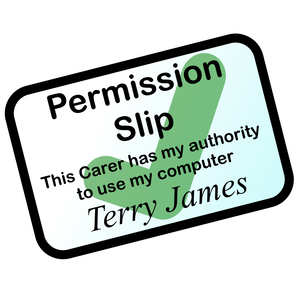

1. The goal is control. That means giving the Client control and not taking it away from him or her. If remote controls are in use, the Carer should not take control but pass the control of the situation to the Client (Barlow, Wright et al 2002; Greene & Hibbard 2012 ; Foot, Gilburt et al 2014; McDonald C., 2014). If the person is not capable of operating the control, you should always ask for permission to use it and state clearly what you are about to do. Ask permission before each action:

“Is it OK if I lower your head?"

"Is it okay for me to mute the sound on the TV?"

Even if the person is physically incapable of performing some function, ensure that the person is always in control. Never take the bed control without permission and subsequently ask,

“Is it alright to raise the bed?”

The former act negates the latter. When a Carer takes control by removing Client control, this also removes Client dignity. Ensure the Client remains in full control when s/he is alone. Do they have the TV remote? Is the bed control accessible? Is the call button available? I found myself, on numerous occasions, without a means of summoning assistance. It is very worrying, especially if you are in a room on your own. I soon learned to check that I had access to a call button before staff left and I was on my own. That situation is not as threatening for more able Clients (who are not helpless and can get out of bed and move around to do things for themselves), but I was an IRON POD, a prisoner within my bed, held captive by my disability. I was not in control. Early in my first period in hospital following the stroke, I had to call a nurse to look at my catheter bag, which was full. The nurse said,

“Oh Christ!”

and hurried to get a disposable bottle in which to empty it. I then asked the nurse for the bed control. She gave me a quizzical look and asked,

“What do you want that for?”

I explained that I wanted to raise the top of the bed. She asked,

“Do you want to sit up?”

and using the bed control herself proceeded to raise the top of the bed saying,

“Tell me when.”

I protested,

“No, give the control to me.”

My speech was poor, affected by the stroke, and the nurse just carried on in control saying,

“Too high?”

and began lowering the top of the bed! I repeated, as clearly as I was able,

“No, give it to me.”

This time the nurse appeared to understand me and passed me the control stating,

“Fine, do it yourself.”

She was not pleased as she walked away. Carers like to be in control. It is not the Carer that needs to be in control, it is the Client. An example will illustrate this concept further. I had been saving some dental chewing gum on a little piece of tin foil on my bed table. I had a piece of gum every day and I had saved it over a week. It may not have been too hygienic but it was my choice. One morning a Carer spotted the gum on my table and, without asking me, picked it up and threw it in the rubbish bag! I was angry that she had taken away my control. The goal is control. Control over health. Control over Carers. Control over the environment. Control over the gadgets in the environment. Control over my own being. Control is empowering.

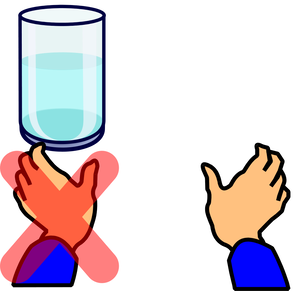

Update October 2021 I had to return to King's Mill Hospital after contracting a serious infection. The standard of care showed no improvement. At lunchtime on Monday 25th October a lady (I don't think that she was a nurse)brought me my dinner and told me to sit myself up for my meal. I reached for the bed control handset to sit myself up carefully. I was not in a good position in bed and raising the top part of the bed would bend me awkwardly and cause me a lot of pain if taken too far without care. Because of my disability, I cannot do things as fast as I used to do and the lady started to raise the top using the control at the bottom of the bed, taking control without asking me. I immediately told her to stop. She replied angrily, informing me patronisingly that I had to sit up to eat or I could choke. I informed her that I was an adult, not a child, and I could raise the top of my bed myself. At which point, she turned away and walked out of my room. To cap it all, when I tried the dinner it was barely warm. I didn’t eat it.

On Monday afternoon, my wife brought me a portable DVD player and some DVDs to watch as there is nothing to do in a single room in hospital. There was a television but they were charging £10 a day for the privilege of watching it. I barely watch TV at home, I wasn’t going to pay ten pounds every day to watch what I would consider poor quality programmes. The DVD player had a sprung top which, when opened, formed the screen. That evening I decided to watch a film and tried to open the lid on the player such that I could insert the DVD and play the movie. Opening a sprung lid with just one functioning hand is really difficult. I spent half an hour trying to balance the player on my legs, while in bed (not sitting up fully), at the same time, endeavouring to open a lid that was fighting to remain closed. At 21:30, I gave up my attempt and decided that I required some assistance. I pressed the nurse call button. Fifteen minutes later, I was thirsty so I reached for my drink and took a few sips. Attached to my cannula was a tube running down from a saline bag. The tube ran through a very annoying device that regulated and monitored the flow. Annoying because it would emit a continuous series of loud beeps when it encountered any issue and I had no means of stopping the beeps myself without summoning a nurse. Raising my good arm to take a drink, set the device off and I was subjected to continuing loud beeping. Why the nurses didn’t put the cannula in my paralysed arm which, obviously, didn’t move, I will never know. Putting it in my functional arm meant that I could not raise it to have a drink or adjust my glasses or scratch my nose without setting off that darn alarm. I had called for a nurse at 21:30, the drip feed alarm went off at 21:45, but help did not arrive until 22:15, some 45 minutes after I had called for help. If I had been in serious trouble, I could have died before anyone answered my call for help. I timed every response while in hospital. A habit I developed during my previous stays there following my stroke a year before. The average time it took a nurse to respond to the nurse call button was 15 minutes! 45 minutes was even worse. The nurse that came was called Alice. I told her my tale and she apologised profusely. Alice explained that she had been on the medication round and was therefore busy with other duties. I expressed concern that there should be other nurses available to answer calls for help. Alice said that there was one other nurse on duty but didn’t know what she was doing or why she hadn’t responded. Alice was very good and very caring and very helpful, I took an instant liking to her. I don’t have a negative word to say about her. However, 45 minutes to respond to what, potentially, may have been a serious distress call is appalling and unacceptable in any hospital, let alone one that proudly displays an ‘outstanding’ award for care from the CQC inspectorate in its entrance hall.

On the following day, nurses came to adjust my position and make me comfortable but left me quickly to attend to another matter. However, they left me without:

• access to my nurse call button;

• access to the bed control handset;

• a bedside table which they had moved in order to help me but not replaced;

• access to a drink. My drinks were on my bed table which was moved;

• access to entertainment (also on my bed table).

I was completely helpless. I could not call for help, I could not reach my nurse call button. I could not even adjust my position. I simply had to wait until someone happened to walk into my room. I could have been stranded for hours before that happened but, as luck would have it, my wife walked in a few minutes later on her daily visit. The whole situation was a further example of the quality of the care practice in the hospital. Surely, it just couldn't be happening to me?

“Is it OK if I lower your head?"

"Is it okay for me to mute the sound on the TV?"

Even if the person is physically incapable of performing some function, ensure that the person is always in control. Never take the bed control without permission and subsequently ask,

“Is it alright to raise the bed?”

The former act negates the latter. When a Carer takes control by removing Client control, this also removes Client dignity. Ensure the Client remains in full control when s/he is alone. Do they have the TV remote? Is the bed control accessible? Is the call button available? I found myself, on numerous occasions, without a means of summoning assistance. It is very worrying, especially if you are in a room on your own. I soon learned to check that I had access to a call button before staff left and I was on my own. That situation is not as threatening for more able Clients (who are not helpless and can get out of bed and move around to do things for themselves), but I was an IRON POD, a prisoner within my bed, held captive by my disability. I was not in control. Early in my first period in hospital following the stroke, I had to call a nurse to look at my catheter bag, which was full. The nurse said,

“Oh Christ!”

and hurried to get a disposable bottle in which to empty it. I then asked the nurse for the bed control. She gave me a quizzical look and asked,

“What do you want that for?”

I explained that I wanted to raise the top of the bed. She asked,

“Do you want to sit up?”

and using the bed control herself proceeded to raise the top of the bed saying,

“Tell me when.”

I protested,

“No, give the control to me.”

My speech was poor, affected by the stroke, and the nurse just carried on in control saying,

“Too high?”

and began lowering the top of the bed! I repeated, as clearly as I was able,

“No, give it to me.”

This time the nurse appeared to understand me and passed me the control stating,

“Fine, do it yourself.”

She was not pleased as she walked away. Carers like to be in control. It is not the Carer that needs to be in control, it is the Client. An example will illustrate this concept further. I had been saving some dental chewing gum on a little piece of tin foil on my bed table. I had a piece of gum every day and I had saved it over a week. It may not have been too hygienic but it was my choice. One morning a Carer spotted the gum on my table and, without asking me, picked it up and threw it in the rubbish bag! I was angry that she had taken away my control. The goal is control. Control over health. Control over Carers. Control over the environment. Control over the gadgets in the environment. Control over my own being. Control is empowering.

Update October 2021 I had to return to King's Mill Hospital after contracting a serious infection. The standard of care showed no improvement. At lunchtime on Monday 25th October a lady (I don't think that she was a nurse)brought me my dinner and told me to sit myself up for my meal. I reached for the bed control handset to sit myself up carefully. I was not in a good position in bed and raising the top part of the bed would bend me awkwardly and cause me a lot of pain if taken too far without care. Because of my disability, I cannot do things as fast as I used to do and the lady started to raise the top using the control at the bottom of the bed, taking control without asking me. I immediately told her to stop. She replied angrily, informing me patronisingly that I had to sit up to eat or I could choke. I informed her that I was an adult, not a child, and I could raise the top of my bed myself. At which point, she turned away and walked out of my room. To cap it all, when I tried the dinner it was barely warm. I didn’t eat it.

On Monday afternoon, my wife brought me a portable DVD player and some DVDs to watch as there is nothing to do in a single room in hospital. There was a television but they were charging £10 a day for the privilege of watching it. I barely watch TV at home, I wasn’t going to pay ten pounds every day to watch what I would consider poor quality programmes. The DVD player had a sprung top which, when opened, formed the screen. That evening I decided to watch a film and tried to open the lid on the player such that I could insert the DVD and play the movie. Opening a sprung lid with just one functioning hand is really difficult. I spent half an hour trying to balance the player on my legs, while in bed (not sitting up fully), at the same time, endeavouring to open a lid that was fighting to remain closed. At 21:30, I gave up my attempt and decided that I required some assistance. I pressed the nurse call button. Fifteen minutes later, I was thirsty so I reached for my drink and took a few sips. Attached to my cannula was a tube running down from a saline bag. The tube ran through a very annoying device that regulated and monitored the flow. Annoying because it would emit a continuous series of loud beeps when it encountered any issue and I had no means of stopping the beeps myself without summoning a nurse. Raising my good arm to take a drink, set the device off and I was subjected to continuing loud beeping. Why the nurses didn’t put the cannula in my paralysed arm which, obviously, didn’t move, I will never know. Putting it in my functional arm meant that I could not raise it to have a drink or adjust my glasses or scratch my nose without setting off that darn alarm. I had called for a nurse at 21:30, the drip feed alarm went off at 21:45, but help did not arrive until 22:15, some 45 minutes after I had called for help. If I had been in serious trouble, I could have died before anyone answered my call for help. I timed every response while in hospital. A habit I developed during my previous stays there following my stroke a year before. The average time it took a nurse to respond to the nurse call button was 15 minutes! 45 minutes was even worse. The nurse that came was called Alice. I told her my tale and she apologised profusely. Alice explained that she had been on the medication round and was therefore busy with other duties. I expressed concern that there should be other nurses available to answer calls for help. Alice said that there was one other nurse on duty but didn’t know what she was doing or why she hadn’t responded. Alice was very good and very caring and very helpful, I took an instant liking to her. I don’t have a negative word to say about her. However, 45 minutes to respond to what, potentially, may have been a serious distress call is appalling and unacceptable in any hospital, let alone one that proudly displays an ‘outstanding’ award for care from the CQC inspectorate in its entrance hall.

On the following day, nurses came to adjust my position and make me comfortable but left me quickly to attend to another matter. However, they left me without:

• access to my nurse call button;

• access to the bed control handset;

• a bedside table which they had moved in order to help me but not replaced;

• access to a drink. My drinks were on my bed table which was moved;

• access to entertainment (also on my bed table).

I was completely helpless. I could not call for help, I could not reach my nurse call button. I could not even adjust my position. I simply had to wait until someone happened to walk into my room. I could have been stranded for hours before that happened but, as luck would have it, my wife walked in a few minutes later on her daily visit. The whole situation was a further example of the quality of the care practice in the hospital. Surely, it just couldn't be happening to me?

2. Stop banging. One time, while in hospital, I found myself with no access to a nurse call button. I could not shout,as a result of the stroke I could hardly speak and, when I did manage to speak, it was barely intelligible. Needing assistance, I improvised and used the bed control pendant to bang on the bed frame. The unorthodox technique worked in that it got attention but I was scolded (banging was ‘inconsiderate of other patients’) and I had the bed control taken away and moved out of my reach! However, the nurse did give me the nurse call button but it was at the cost of losing my bed control. Ensure the Client always has an acceptable means of summoning assistance. Never punish a Client by removing control. The removal of a Patient's control is the removal of a Patient's dignity.

3. Going up? Ensure the hoist is in good working order (Health and Safety Executive 2011; Bainbridge 2019). If the Client is capable, put control of the hoist in the Client’s hands. Give control of the hoist to the person to be hoisted. The Carers can ensure that hoisting is undertaken safely even when they are not directly holding the hoist control. If the individual is physically and cognitively competent, the role of the Carer is to empower the Client and enable him / her to do it for him / herself. If there is no other option but for Carers to operate the hoist, it is important that they allow the Client to take charge of the situation by asking the person to give instructions on what actions to take and when to take them. Client instructions need not be verbal, sign or gesture are equally as good; these modes of communication still allow the Client control of the situation. Do not take control away from the Client, allow the Client gradually to take control away from you. The goal is control. Client control.

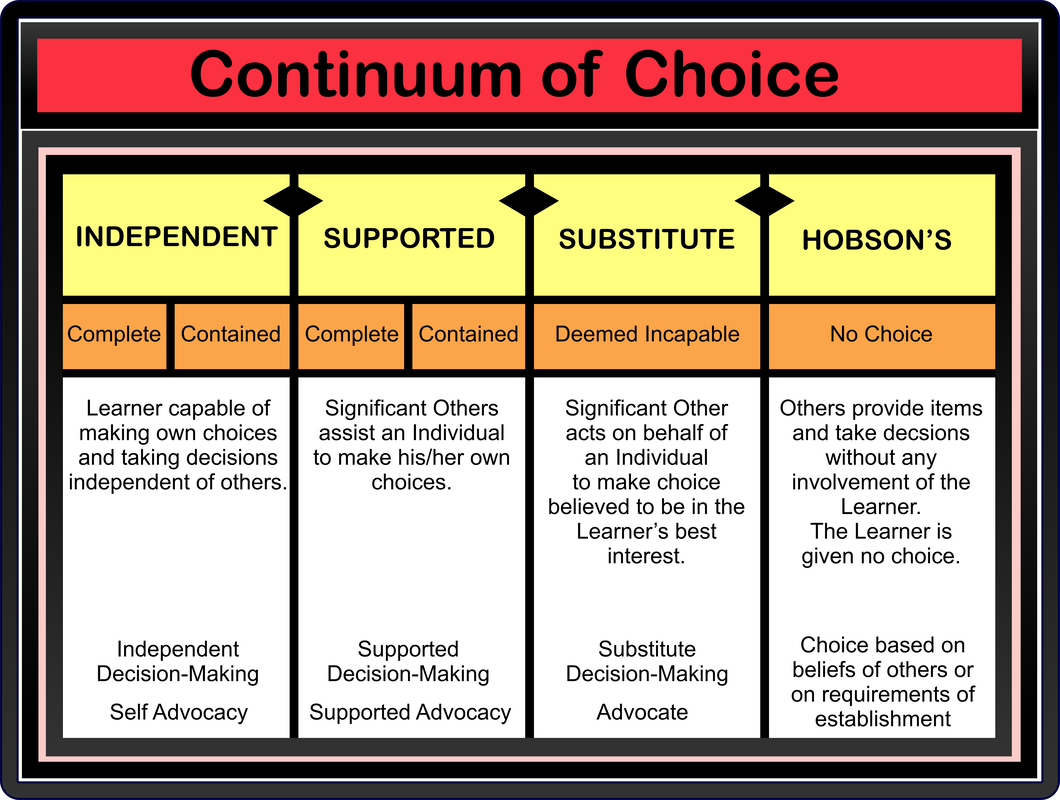

4. I’m in charge. Who is in charge? (Haug & Lavin 1981; Veatch 2008) A Carer entered my room while I was watching a film. She took the TV remote off my bed and paused the film without asking. I was somewhat annoyed! Her actions implied that she was in charge of the situation and, now that she was present, I was subject to her will. The question of who is in ultimate control of a situation can be contentious. If a Client is saying one thing and the Client’s spouse (or Significant Other) another and the Carer’s belief is yet a further option, whose rule is correct? Sometimes this can be problematic. As a general principle, the Client should always have the guiding voice, although it may prove very difficult to ignore the spouse! Suppose the Client is not cognitively competent, should the spouse’s wishes prevail? The answer is not a simple ‘yes’. The Client’s wishes should always be a priority but an other’s wishes may overrule a Client if the Client’s wish is D.U.B.I.O.U.S:

- Dangerous,

- Unreasonable (impartial others would judge it to be so),

- Bad (for the Client), (who decides what is bad for the Client?!)

- Impossible to undertake,

- Outside your remit, (there may be rules that do not permit Carers to perform specific actions. This includes any directive written into the Client’s Care Plan),

- Unintelligible or Unworkable,

- Specialist (requires a professional – a person specifically qualified for that role)

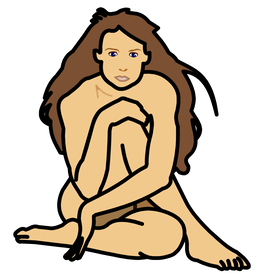

5. Empathy. Anyone’s life can change, in an instant, overnight. It could be you lying naked in the bed unable to care for yourself, unable to move without assistance. How would you feel? How would you want to be treated? (Raab 2014; Svenaeus 2015). While there would be gratitude to those who gave up their time to come and do anything just to be of help (family, friends, old colleagues, volunteers) there would be a far greater expectation of others who were being paid to provide assistance, especially if it were your money that was used. If you were paying, would you expect a basic standard of service? Would you be concerned about the issues raised on this page? Imagine being naked while other virtual strangers were touching intimate parts of your anatomy. That is what will happen if you become an IRON POD club member. It is a club that anyone can join: male or female, rich or poor, black or white, old or young. It is a club to which no person chooses to belong. Why? Because the rules are so harsh. The first rule of the IRON POD club is members don't elect to join the club, the club elects to join a member. A person has only a limited ability in preventing membership. That is because most people believe that it will never happen to them. The annual membership fee is very large and, once a member, it is almost impossible to leave.

6. Mrs Stretch and Mr Bendy. Unless very special, a person’s elbows only bend in one direction. Why, then, do some Carers place items, such as the bed control, TV remote, etc., in positions that require the Client to perform superhuman contortions in order to be able to access them? Placing items in impossible to reach locations is removing Client control. Removing control is removing dignity. Maintenance of the Client’s dignity is extremely important (Cairns, Williams et al 2013; Higgins 2020; Hammar, Alam et al 2021). The goal is control. The goal is Client control. (Examples of removal of Client dignity can be found in a Unison publication available here: https://www.unison.org.uk/content/uploads/2015/06/23070.pdf)

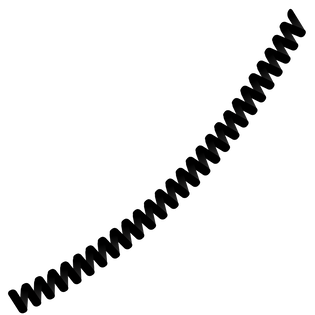

7. Enable with the cable. Controls for hospital-style beds are usually attached to the bed via a spiralling cable. This cable has a habit of becoming snagged down the side of the bed such that only a small amount is available to the Client in attempting to control the bed’s position. The Client ends up fighting against the spring of the spiral to gain control. Carers have stood and watched me struggle with the bed control, fighting against the springy cable and not asked if I needed help. When a person has only one working hand, trying to operate controls on an item attached to a spring is something of a problem! As soon as an attempt is made to press a button, the bed control flies away from the hand pulled by the spring of the cable!! It is either hold the control against the spring of the cable or operate the control itself. It is very difficult to do both at the same time with just one hand. On passing a bed control to a Client, always ensure that the cable is free.

It is a simple matter for a Carer to ensure the bed control is within reach, easily accessible, and the cable is free from snagging on the side of the bed. The Client should be able to use the control after Carers leave without any problems. I am amazed that in this day and age that there needs to be a cable at all. Why isn't the bed control remote?

I have been having care for over a year now and still the majority of Carers pass me the bed control without freeing the cable. I have to struggle with the cable until someone notices and helps.

It is a simple matter for a Carer to ensure the bed control is within reach, easily accessible, and the cable is free from snagging on the side of the bed. The Client should be able to use the control after Carers leave without any problems. I am amazed that in this day and age that there needs to be a cable at all. Why isn't the bed control remote?

I have been having care for over a year now and still the majority of Carers pass me the bed control without freeing the cable. I have to struggle with the cable until someone notices and helps.

8. Assess not Assume (Ryden & Knopman 1989). Do not assume because ass-u-me makes an ass out of u (you) and me (pun originally attributed to Oscar Wilde). Do not assume that a Client cannot comprehend questions or instructions. Do not assume that a Client is incapable of performing a task even if the Client’s ability is unclear. Rather, clarify the situation by asking the person. Never perform an action on ‘behalf of an individual’ assuming the person cannot do it for him / herself. Take away a Client’s control and take away a Client’s dignity. Under time constrictions, it is often easier / quicker to ‘do for’. This is not good practice.

Do for = poor practice.

Do with = better practice.

Enabling the Client to do for him / herself = best practice.

Do for = poor practice.

Do with = better practice.

Enabling the Client to do for him / herself = best practice.

Communication

V-Pen System

V-Pen System

Communication is important.

Speech is power in our society. Hence, it should surprise no one that freedom of speech is the first right guaranteed to all Americans in the Bill of Rights. Deprived of speech or another means of effective communication, individuals become invisible. They are simply not heard. They are silenced. And, when people are silenced, others quickly lose sight of their right to be a part of humanity! (Bryen D. 1993)

The limits of my language mean the limits of my world (Wittgenstein L. 1953)

No one in this day and age can possibly underestimate the importance of language. We are surrounded by talking (Jeffree D. & McConkey R. 1976)

Speech is the most important thing we have. It makes us a person and not a thing. No one should ever have to be a 'thing.' (Joseph D. 1986)

The ability to communicate, that is, to interact socially and to make needs and wants known, is central to the determination of an individual’s quality of life. The power of communication is especially important for the severely handicapped .... these individuals face a lifetime of substantial, if not total dependence on others; hence, their ability to communicate and establish some control over their environment must be recognized as a priority in their programming (Light J., McNaughton D., & Parnes P. 1986)

And to be defective in language, for a human being, is one of the most desperate of calamities, for it is only through language that we enter fully into our human estate and culture, communicate freely with our fellows, acquire and share information. If we cannot do this, we will be bizarrely disabled and cut off - whatever our desires, or endeavours, or native capacities. And indeed, we may be so little able to realize our intellectual capacities as to appear mentally defective. (Sacks O. 1989)

My basic problem was one I’ve encountered through my whole life. When you can’t talk, and people believe that your mind is as handicapped as your body, it’s awfully difficult to change their opinion. (Sienkiewicz‑Mercer R. & Kaplan S. B. 1989)

A communication handicap is quite different from other handicaps. It affects the manner in which you relate to other people and how they relate to you, it pervades everything you do (Oakley M. 1991)

Imagine a life without words! Trappist monks opt for it. But most of us would not give up words for anything. Every day we utter thousands and thousands of words. Communicating our joys, fears, opinions, fantasies, wishes, requests, demands, feelings - and the occasional threat or insult - is a very important aspect of being human. The air is always thick with our verbal emissions. There are so many things we want to tell the world. Some of them are important, some of them are not. But we talk anyway - even when we know that what we are saying is totally unimportant. We love chitchat and find silent encounters awkward, or even oppressive. A life without words would be a horrendous privation. (Katamba F. 1994)

Language is so tightly woven into human experience that it is scarcely possible to imagine life without it. Chances are that if you find two or more people together anywhere on earth, they will soon be exchanging words. When there is no on to talk with, people talk to themselves, to their dogs, even to their plants. In our social relations, the race is not to the swift but to the verbal - the spellbinding orator, the silver-tongued seducer, the persuasive child who wins the battle of wits against a brawnier parent. Aphasia, the loss of language following brain injury, is devastating, and in severe cases family members may feel that the whole person is lost forever. (Pinker S. 1994)

People with communications deficits face particular challenges unique to them. It is through communicative interactions that individuals are able to transcend the barriers erected by disability. Being unable to speak creates special problems. A well-used communication aid can be an effective tool for integrating people with communication disabilities into the culture of a particular workplace. (Dickerson L. 1995)

And language remains our greatest treasure, for without it we are confined to a world that, while not one of social isolation, is surely one that is a great deal less rich. Language makes us members of a community, providing us with the opportunity to share knowledge and experiences in a way no other species can. (Dunbar R. 1996)

Communication is the basis of learning. Communication is essential for the acquisition of knowledge. How are we to tell whether an individual (with severe physical impairment) has internalised language unless s/he can communicate? It is imperative that the neurological development of language skills are given every opportunity to proceed without impediment (Jones A.P. 1996)

A stroke can take away the power of speech. My stroke left me with very poor speech. On good days I can make myself understood but on bad days I have no speech at all. I have worked with AAC (Alternative and Augmentative Communication) throughout my working life. I have taught AAC, designed and developed AAC, marketed AAC, and lectured on AAC all over the world. After the stroke I became a consumer of AAC. I am probably the only person in the world to have occupied each of those roles. The irony of becoming a user of AAC is not lost on me. While in hospital I used a combination of very poor natural speech, my V-Pen and board, Makaton signing, and writing in a notebook at various times in order to communicate and get what I needed to say across to others. Makaton signing is tailored for use with two able hands, I only had one functioning upper limb following the stroke and even that was not very able. I had to use Makaton creatively, adapting signs made using two hands into a single handed form. It would not have mattered if I had the use of my left hand however because none of my nurses knew any Makaton. I had to teach them some signs by signing a single word and then writing down its meaning in my notebook. A very slow way to communicate! I also used my V-Pen and board. The V-Pen is a clever pen-shaped device that can recognise symbols and speak their meaning when a symbol is touched. I was involved in the system's development when I worked for Unlimiter in Taipei, Taiwan. The nurses were more interested in the Pen, it's technology, and how it worked than what I was trying to say. Many times I forgot my intended message because I became distracted in performing to an audience of nurses showing them the Pen! I had built several communication boards for use with the Pen whilst in Taiwan which I had at home. My wife brought them for me when she came to visit. While the V-Pen was a perfect AAC system for use in hospital, unfortunately the boards that I designed were not! They did not have the vocabulary necessary for use on a hospital ward.I busied myself with the design of a board that would be highly suited for this purpose and could be available on every hospital ward throughout the world. The V-Pen system is perfect for that situation because it is small, portable, and requires virtually no learning; a person could learn to use it in seconds. The spelling board option can say virtually anything provided the Patient can spell. Put that together with a couple of symbol boards and you have a really good communication system for nurses to loan to Patients during their hospital stay.

Yes, communication matters. My lack of effective communication let me down on several occasions during my time in hospital. Some are detailed on this web page. I continue to have communication difficulties nearly a year post-stroke. I guess I will have them for the remainder of my life. Silence is not golden despite what the song says. I am already beginning to notice subtle differences in the way I am treated by others. Others are uncomfortable with silence and, as I take longer to respond to communication from other people, will 'jump in' and continue communicating in what, I presume, is an effort to ease the discomfort that I must be feeling not being able to communicate effectively.There have been other barely perceivable changes too. I will not list them here but rather attempt to cover each of them in the points that I make on the remainder of this page.

I am going to have to think about my primary mode of communication for the future if my speech continues to fail me. I have considered the development of a one-handed Makaton signing system which I have tentatively called 'Maka-One'. I have not discussed my idea with the team at Makaton yet, they may not like my idea. Presently, that is all it is, an idea. There are a few single-handed sign languages already in existence (I believe Irish Sign Language is among them) but, I would have to learn them. I already know Makaton and have started adapting it for my own personal use. I believe Beyoncé has a song about it whose lyrics are something like “All the single handers, all the single signers, if you like it then you shoulda put a patenting on it”. Well, it is something near to that, I think!! Seriously, signing with just a single available hand is no joke! Having to use my one good arm and hand for everything is putting a strain on it and I am already beginning to notice it is starting to feel uncomfortable in use and it is hurting a little to bend my fingers into a fist. This is somewhat worrying for future signing, for instance. I try to take it easier but, then, I have no hands and how do I interact with my environment? I spend a great deal of the average day completely on my own, alone in bed in a room unable to get out of bed and do any of the things I used to take for granted. I have an emergency contact button which, if I were to use it, would contact an outside service to summon help. In such a situation, my speech would certainly fail me. It is good that the line knows who and where I am and has the details of emergency contacts, even if I could not say a word during any use. The service is not free, it costs me around £20 per month. Disability doesn't come cheap in 2021. I suspect it has always been so.

Speech is power in our society. Hence, it should surprise no one that freedom of speech is the first right guaranteed to all Americans in the Bill of Rights. Deprived of speech or another means of effective communication, individuals become invisible. They are simply not heard. They are silenced. And, when people are silenced, others quickly lose sight of their right to be a part of humanity! (Bryen D. 1993)

The limits of my language mean the limits of my world (Wittgenstein L. 1953)

No one in this day and age can possibly underestimate the importance of language. We are surrounded by talking (Jeffree D. & McConkey R. 1976)

Speech is the most important thing we have. It makes us a person and not a thing. No one should ever have to be a 'thing.' (Joseph D. 1986)

The ability to communicate, that is, to interact socially and to make needs and wants known, is central to the determination of an individual’s quality of life. The power of communication is especially important for the severely handicapped .... these individuals face a lifetime of substantial, if not total dependence on others; hence, their ability to communicate and establish some control over their environment must be recognized as a priority in their programming (Light J., McNaughton D., & Parnes P. 1986)

And to be defective in language, for a human being, is one of the most desperate of calamities, for it is only through language that we enter fully into our human estate and culture, communicate freely with our fellows, acquire and share information. If we cannot do this, we will be bizarrely disabled and cut off - whatever our desires, or endeavours, or native capacities. And indeed, we may be so little able to realize our intellectual capacities as to appear mentally defective. (Sacks O. 1989)

My basic problem was one I’ve encountered through my whole life. When you can’t talk, and people believe that your mind is as handicapped as your body, it’s awfully difficult to change their opinion. (Sienkiewicz‑Mercer R. & Kaplan S. B. 1989)

A communication handicap is quite different from other handicaps. It affects the manner in which you relate to other people and how they relate to you, it pervades everything you do (Oakley M. 1991)

Imagine a life without words! Trappist monks opt for it. But most of us would not give up words for anything. Every day we utter thousands and thousands of words. Communicating our joys, fears, opinions, fantasies, wishes, requests, demands, feelings - and the occasional threat or insult - is a very important aspect of being human. The air is always thick with our verbal emissions. There are so many things we want to tell the world. Some of them are important, some of them are not. But we talk anyway - even when we know that what we are saying is totally unimportant. We love chitchat and find silent encounters awkward, or even oppressive. A life without words would be a horrendous privation. (Katamba F. 1994)

Language is so tightly woven into human experience that it is scarcely possible to imagine life without it. Chances are that if you find two or more people together anywhere on earth, they will soon be exchanging words. When there is no on to talk with, people talk to themselves, to their dogs, even to their plants. In our social relations, the race is not to the swift but to the verbal - the spellbinding orator, the silver-tongued seducer, the persuasive child who wins the battle of wits against a brawnier parent. Aphasia, the loss of language following brain injury, is devastating, and in severe cases family members may feel that the whole person is lost forever. (Pinker S. 1994)

People with communications deficits face particular challenges unique to them. It is through communicative interactions that individuals are able to transcend the barriers erected by disability. Being unable to speak creates special problems. A well-used communication aid can be an effective tool for integrating people with communication disabilities into the culture of a particular workplace. (Dickerson L. 1995)

And language remains our greatest treasure, for without it we are confined to a world that, while not one of social isolation, is surely one that is a great deal less rich. Language makes us members of a community, providing us with the opportunity to share knowledge and experiences in a way no other species can. (Dunbar R. 1996)

Communication is the basis of learning. Communication is essential for the acquisition of knowledge. How are we to tell whether an individual (with severe physical impairment) has internalised language unless s/he can communicate? It is imperative that the neurological development of language skills are given every opportunity to proceed without impediment (Jones A.P. 1996)

A stroke can take away the power of speech. My stroke left me with very poor speech. On good days I can make myself understood but on bad days I have no speech at all. I have worked with AAC (Alternative and Augmentative Communication) throughout my working life. I have taught AAC, designed and developed AAC, marketed AAC, and lectured on AAC all over the world. After the stroke I became a consumer of AAC. I am probably the only person in the world to have occupied each of those roles. The irony of becoming a user of AAC is not lost on me. While in hospital I used a combination of very poor natural speech, my V-Pen and board, Makaton signing, and writing in a notebook at various times in order to communicate and get what I needed to say across to others. Makaton signing is tailored for use with two able hands, I only had one functioning upper limb following the stroke and even that was not very able. I had to use Makaton creatively, adapting signs made using two hands into a single handed form. It would not have mattered if I had the use of my left hand however because none of my nurses knew any Makaton. I had to teach them some signs by signing a single word and then writing down its meaning in my notebook. A very slow way to communicate! I also used my V-Pen and board. The V-Pen is a clever pen-shaped device that can recognise symbols and speak their meaning when a symbol is touched. I was involved in the system's development when I worked for Unlimiter in Taipei, Taiwan. The nurses were more interested in the Pen, it's technology, and how it worked than what I was trying to say. Many times I forgot my intended message because I became distracted in performing to an audience of nurses showing them the Pen! I had built several communication boards for use with the Pen whilst in Taiwan which I had at home. My wife brought them for me when she came to visit. While the V-Pen was a perfect AAC system for use in hospital, unfortunately the boards that I designed were not! They did not have the vocabulary necessary for use on a hospital ward.I busied myself with the design of a board that would be highly suited for this purpose and could be available on every hospital ward throughout the world. The V-Pen system is perfect for that situation because it is small, portable, and requires virtually no learning; a person could learn to use it in seconds. The spelling board option can say virtually anything provided the Patient can spell. Put that together with a couple of symbol boards and you have a really good communication system for nurses to loan to Patients during their hospital stay.

Yes, communication matters. My lack of effective communication let me down on several occasions during my time in hospital. Some are detailed on this web page. I continue to have communication difficulties nearly a year post-stroke. I guess I will have them for the remainder of my life. Silence is not golden despite what the song says. I am already beginning to notice subtle differences in the way I am treated by others. Others are uncomfortable with silence and, as I take longer to respond to communication from other people, will 'jump in' and continue communicating in what, I presume, is an effort to ease the discomfort that I must be feeling not being able to communicate effectively.There have been other barely perceivable changes too. I will not list them here but rather attempt to cover each of them in the points that I make on the remainder of this page.

I am going to have to think about my primary mode of communication for the future if my speech continues to fail me. I have considered the development of a one-handed Makaton signing system which I have tentatively called 'Maka-One'. I have not discussed my idea with the team at Makaton yet, they may not like my idea. Presently, that is all it is, an idea. There are a few single-handed sign languages already in existence (I believe Irish Sign Language is among them) but, I would have to learn them. I already know Makaton and have started adapting it for my own personal use. I believe Beyoncé has a song about it whose lyrics are something like “All the single handers, all the single signers, if you like it then you shoulda put a patenting on it”. Well, it is something near to that, I think!! Seriously, signing with just a single available hand is no joke! Having to use my one good arm and hand for everything is putting a strain on it and I am already beginning to notice it is starting to feel uncomfortable in use and it is hurting a little to bend my fingers into a fist. This is somewhat worrying for future signing, for instance. I try to take it easier but, then, I have no hands and how do I interact with my environment? I spend a great deal of the average day completely on my own, alone in bed in a room unable to get out of bed and do any of the things I used to take for granted. I have an emergency contact button which, if I were to use it, would contact an outside service to summon help. In such a situation, my speech would certainly fail me. It is good that the line knows who and where I am and has the details of emergency contacts, even if I could not say a word during any use. The service is not free, it costs me around £20 per month. Disability doesn't come cheap in 2021. I suspect it has always been so.

9. Sign of the times. All Carers should know some basic (Makaton) signs, such that they will be able to understand if a Client is trying to communicate, or to be able to demonstrate to a Client how to make basic communication; for example, how to sign ‘yes’ and ‘no’. If sign is not known to the Carers, ask the Client to demonstrate some basic signs. I was signing ‘I don’t know’ this morning slowly several times. The Carers, rather than see my signs as an answer to the question they had just asked of me, decided that I was pointing out that my chest needed washing. They hadn’t a clue and seemingly preferred to remain ignorant of ways to make any communication between us a lot better. Communication matters - Always attempt to establish a meaningful means of communication for and with the Client. It may be that the Client utilises an alternative form of communication (for example, a sign or symbol system). In which case, attempt to learn how able s/he is in its use. If you are not competent in sign language, ask your Client to show you how s/he makes basic signs. For example, yes, no, please, thank you, pain and any others that it might be useful to know. Be a little wary of copying a Client’s signs without checking that the sign is correct. While it is acceptable for a Client to use idiosyncratic signing (for example, I only have use of my right hand and so I have adapted my knowledge of Makaton to work with only one hand) (Note: I believe Irish Sign Language only requires the use of one hand), idiosyncratic signing is not acceptable for the Carers! Playing Chinese Whispers with sign language is sure to result in very strange hand movements recognisable by no one. Learn to recognise the signs as used by the Client. It can be very frustrating for a Client, when signing, if the Carers do not comprehend the message. A good place to learn some basic (Makaton) signs is to search for ‘Mr Tumble’ videos on YouTube. ‘Mr Tumble’ is not just for children. Everyone should know some signs: schools should teach sign language. Sign language should be an option on the curriculum alongside French and German. If the Client has apparently no recognisable means of communication, and a significant cognitive impairment, it is possible to attempt to turn an already existing behaviour into a meaningful mode of communication (Ware 2012). For example, if the Client is able to move any part of his / her anatomy purposefully, it may be possible to associate that particular movement with a specific concept by always responding to it in exactly the same way. Moving a hand slightly to the right (or slightly lifting a finger) might be taken to mean ‘yes’, for example. The consistency of the response establishing a relationship, over time, such that a movement, which a Client was already capable of performing, becomes an idiosyncratic sign for the word. It is very important that all involved with the Client respond consistently, in the same way, to establish the link. Significant Others should be aware of all that is attempted. Where a Client has an existing method of alternative communication, it is very important that Carers do not impede its access for any longer than is essential. A symbol book or chart may need to be out of the way, while rolling, for example, but the Client should have access to it as soon as possible after. Do not deprive the Client of a means of communication for longer than is necessary.

Update (15th Aug '21): This morning the Carers asked me a question. By the time I had the chance to answer in sign, they had already asked several more questions. I signed "I don't know". The Carers hadn't got a clue what I was saying. They would not know which of the questions they had asked to which my signing was the response, because they had moved on so far beyond the original question. In the end, my wife had to come and act as an interpreter to prevent them from carrying out an unnecessary task based on an incorrect assumption of the meaning of my signing.

Update (15th Aug '21): This morning the Carers asked me a question. By the time I had the chance to answer in sign, they had already asked several more questions. I signed "I don't know". The Carers hadn't got a clue what I was saying. They would not know which of the questions they had asked to which my signing was the response, because they had moved on so far beyond the original question. In the end, my wife had to come and act as an interpreter to prevent them from carrying out an unnecessary task based on an incorrect assumption of the meaning of my signing.

10. Don't ask her, ask me. As previously noted, questions on care should be addressed to the Client and not to some other member of the Client’s family. It is truly demeaning to Clients to ignore them completely and address questions to others. It is the old ‘does he take sugar?’ issue (Wagner 1991; Hogg & Wilson 2004). Radio 4 (UK) used to broadcast a weekly series entitled ‘Does He Take Sugar?’ (It started in 1977 and ran for about twenty years) in which it covered the treatment of the disabled. The title of the program refers to an all-to-frequent occurrence, in which a person asks another (other than the person with the disability) a question about a topic avoiding talking to the person with the disability. People often discuss items concerning someone with a disability, while s/he is present, and do not include the person even though s/he can speak for him / herself. The radio series made this type of thing explicit and gave People Of Disability (POD) a voice. My wife has replied to people, behaving in this fashion, on several occasions,

“I don’t know. Why don’t you ask him?”

Always address questions to Clients. Even if incapable of verbal communication, the Client may still be able to respond using an alternative methodology. If another family member is around, they are likely to respond on the Client’s behalf if they know the Client is unable to answer for himself / herself for any reason. The Client will always appreciate that the Carers directed question at him / her even though s/he is not able to reply in a comprehensible fashion in the situation. Bypassing the individual completely is both demeaning and very poor practice. If a Client responds in a manner that is incomprehensible, never denigrate the Client’s response system,

“Oh, I don’t understand those stupid signs, can you write it down?”

Rather say,

“I am sorry John, I never learned any sign language, but perhaps you could teach me how you say some basic things when I come the next few times and you will help me to understand you better. Is that OK with you? Does the sign you are making mean Yes?”

“I don’t know. Why don’t you ask him?”

Always address questions to Clients. Even if incapable of verbal communication, the Client may still be able to respond using an alternative methodology. If another family member is around, they are likely to respond on the Client’s behalf if they know the Client is unable to answer for himself / herself for any reason. The Client will always appreciate that the Carers directed question at him / her even though s/he is not able to reply in a comprehensible fashion in the situation. Bypassing the individual completely is both demeaning and very poor practice. If a Client responds in a manner that is incomprehensible, never denigrate the Client’s response system,