The Development of Contingency Awareness in

Individuals Experiencing PMLD (IEPMLD) and beyond: Theory and Practice.

"The interventions and results show that rather simple and easily implemented contingency learning games can have rather dramatic effects on child learning, which included extended benefits to both the child and his or her caregivers. Interestingly, many of the interventions used with young children with profound developmental delays and multiple disabilities do not include the promotion of child behavior competence (Dunst, Raab, Wilson, & Parkey, 2007; Winefield, 1983). Rather, the interventions typically involve non-contingent stimulation to evoke child behavior or passive manipulation of child movements."

(Raab, Dunst, Wilson, & Parkey 2009)

"This suggests that response-contingent learning opportunities, and especially for children who demonstrate few instrumental behavior, is warranted as a form of early childhood intervention"

(Raab, Dunst, Wilson, & Parkey 2009)

"While they were saying among themselves it cannot be done, it was done." (Helen Keller)

"I do not want the peace which passeth understanding, I want the understanding which bringeth peace." (Helen Keller)

Contingency Awareness (often referred to as understanding 'cause and effect') is a consciousness of a relationship between two different events; that is, an understanding of a relationship between actions and the outcomes those actions elicit in the environment. A baby in a cot kicks its legs in a certain way and accidentally makes the mobile, suspended above the cot, move. After some repetitions of the leg kicking, the child begins to form an association between his actions (kicking his leg in a certain way) and the movement of the mobile. At this stage, the child may not understand how the action of his leg is causing the mobile movement but nevertheless still recognises that s/he can exert control and has thus made a connection.

Contingency Awareness is an important milestone for Individuals Experiencing PMLD. However, the combination of cognitive, physical and sensory impairments experienced by many acts as a obstacle to block the typically developing pathway. Indeed, the (inadvertent) actions of Significant Others may have a detrimental contributory effect further increasing the size of the obstacle. As Significant Others routinely:

- anticipate and fulfill the needs of the IEPMLD (Individual Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties);

- block access to experimentation by the IEPMLD;

"Learned helplessness occurs when it is unclear to the learner that he or she is able to exert control over the environment... For many learners, their social history has offered few opportunities to self-select desired objects, people, or activities. At meal times plates are prepared and distributed. Additional serving are provided automatically. Coats are handed out and doors opened when it is time to go. Thus, throughout the day, the caregivers do virtually everything for the learners. Initially, some learners may have attempted to self-select items of interest, but were actively encouraged not to do so." (Reichle, J. 1991 p.141)

"The children's physical disabilities place considerable restrictions on their personal development. There are activities in which they will be unable to participate, and many fields where they will gain only limited experience Part of this limitation is caused primarily not by the motor handicap, however, but by the fact that, due to negative experiences, they believe they are unable to do anything. Later on they will no longer try to do things that they perhaps would have been capable of. They learn that they are dependent on others because others do things for them which they would be unable to manage alone. At the same time they will experience that they are an inconvenience, that they are a hindrance and that the adults are most content when they are passive. The adults' attitude to the children, which the children to a great extent assume themselves (cf. Madge and Fassam 1982), therefore plays a significant role in forming their life and opportunities for personal growth." (Von Tetzchner, S. & Martinsen, H. 1992)

"All children are dependent upon adult caretakers for fulfillment of their physical and emotional needs. In the process of becoming autonomous, children explore and test their world and begin signalling their growing independence to caretakers through physical actions and spoken messages. If provided with an adequate climate for growth, an increasingly solid foundation for independence in adult life will be formed. However, for children with severe communication and/or physical limitations this process of self growth may be overlooked or suppressed. Because many children experiencing the aforementioned challenges are not able to signal their readiness for exploration or independence in traditional ways, parents and other caretakers (e.g. professional service providers, educators, etc.) are inclined to continue to act as direct or indirect agents for fulfilling the child's needs. When later provided with adequate means to express, query, or explore, (e.g. assistive technology) the child may persist in a more passive state due to learned helplessness or learned dependency." (Sweeney, L. 1993)

"The view of oneself as dependent, even as 'helpless' can be hard for many children to shake off. Those with a communication problem may be even more entrenched in patterns of looking to others to speak for them, decide for them and of setting up their parents, siblings and friends as more competent and more responsible than themselves. In some ways it makes for an easier life. It also detracts from the child's potential." (Dalton, P. 1994, page 133)

Over 100 years ago, in a 1895 publication, James Baldwin outlined a relationship between a child's beginning to see actions as the cause of environmental effects and increases in responses of a social/emotional nature such as excitement, laughter, and smiling. Likewise, in studying his own children, similar observations were made by Jean Piaget (1952). In support of these claims, Haith (1972) and McCall (1972) pointed out that, because such cognition is pleasurable, the ability of a child to understand s/he is the cause of a particular environmental consequence produces social-emotional behaviour.

Almost all IEPMLD show at least some contingency awareness:

- Those that hit themselves or poke themselves in the eyes must be 'aware' that doing so brings sensory stimulation: they have made the link between the action (self harm) and response (sensory stimulation);

- Those that rock back and forth must be doing this for some reason. It is generally assumed that this is stimulatory behaviour which brings some reward. At some point the individual must have made this connection and continued the behaviour;

- Those that twirl or flap objects by their eyes or their face at every available moment must have, at some prior point, made a connection between the action and a favourable sensation.

- Those that will reach out and repeatedly tap a switch surface must be doing that continually (until they grow tired of it or until the switch is removed) for some reason. It must be providing the person with some sensory feedback which is fulfilling / motivating in some way. The repeatedness of the actions seems to suggest an awareness of a relationship between the behaviour and the response to it.

The fact that these actions are repeated seems to be indicative of a connection between an action (slapping, rocking, flapping, tapping...) and an (internal) event (favourable sensation). In a sense, these actions, often viewed by staff members pejoratively, have, at least, a positive aspect: if a Learner is behaving in this manner then s/he must have made a connection and, having made one connection, the Learner must be capable of making other connections given the opportunity to do so.

The words 'given the opportunity' begs the questions: 'how do we give?' and 'what opportunities?'. This webpage hopes to provide at least some answers to those questions. One avenue, worthy of further exploration, is the use of (switch activated) assistive technology as a means to this end. This has been recognised since the earlier days of electronic assistive technology:

Research has demonstrated that switch technology can be used successfully to facilitate the formation of contingency awareness in individuals with severe and/or multiple disabilities

(York, Nietupski, & Hamre-Nietupski, 1985).

It is extremely important that we address this area of development by providing frequent, structured opportunities to help Learners gain an understanding of contingency awareness and, thus, discover that they can exercise control over their surroundings. Below are a number of suggestions for ways to assist with the development of contingency awareness. You are, of course, free to adopt, adapt or abrogate any of them. However, Talksense hopes that at least some of what follows will inspire your thinking. Should you have any feedback or wish to suggest further approaches, a form has been provided at the bottom of this webpage for the purpose.

BEST POLEs

BEST = Best Ever Stimulating Thing

What is it the the Learner loves? Is it sweets/candy? Is it a particular game, a TV programme, a particular person? In other words, what is the Best Ever Stimulating Thing for a particular individual? Let's start working with this BEST as the motivator.

POLE = Person Object Location Event

The BEST thing will be a POLE. POLE is an acronym for Person, Object, Location, or Event.

If we can place a tangible POLE at the end of a Learner action (For example: provide the Learner with a POLE as a result of a request using an Augmentative Communication system or activating a switch) then we have a way of moving forward. Not just any sort of POLE! What sort of POLE? Well, a BEST POLE of course.

Here are some ideas:

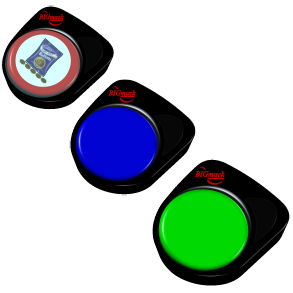

For those that can touch: Start with a single BIGmack (or equivalent device). Label it with an appropriate symbol or a Sensory Surface for the Learner's BEST POLE. By demonstrating, modelling, prompting, or even waiting for accidental access, allow the Learner to 'see' that the activation of the device leads to ( is always followed by) the provision of a BEST POLE. Hopefully, after a number of activations of the BIGmack, the Learner will begin to understand that his/her action (activating the BIGmack) results in a particularly favoured and rewarding event. However, even though a Learner may activate such a device repeatedly, it is difficult to establish intentionality: the Learner may continue to activate a device accidentally (for example) or just be exploring (and thus repeatedly activating) anything that has been placed in the Learner's reach without making any cognitive connection between his or her action and the rewards that seem to be occurring. How could we be more certain of some form of Learner cognizance?

If a baseline is taken in which the BIGmack (or equivalent) is utilised in a different manner (with a different sensory surface or symbol) such that it just plays a short piece of relatively uninteresting music (for example) then, when it is placed within the reach of the Learner, the number of activations (accidental and or purposeful) in a specified time period can recorded. Perhaps such practice might result in 4 activations in the first minute but this tails off afterwards such that it averages at less than one activation a minute. This is our baseline. If we now introduce the BIGmack resulting in the BEST POLE and this results in an increase in activations over time it would seem a reasonable assumption that the difference in Learner behaviour is as a result of some level of cognisance of the situation. As it is always good practice for staff to look for alternative explanations for changes in Learner behaviour, this situation should be no different. Perhaps the Learner is attracted to the BIGmack because it is a different colour (ensure that the same BIGmack is used). Perhaps the Learner is stimulated by the sensory surface that has been used and it is this that is causing the increased response level. How could we eliminate this possibility from our findings? We could swap the sensory surfaces used in the first experience (baseline) with the second and see if this provides similar results. While it is not good practice to use sensory surfaces it such a manner normally, in this instance it is justified. If the repeated baseline with the new sensory surface yields similar results to the original baseline then it cannot be the sensory surface itself that is responsible for the change in Learner response.

"Eliminate all other factors, and the one which remains must be the truth." (Sherlock Holmes, The sign of Four, Chapter 1, p. 92)

Once basic contingency awareness has been established and we have a Learner activating a BIGmack (or equivalent) to obtain a reward, it becomes necessary to step up the level of difficulty of the task very slightly, further to ascertain Learner cognisance. If we add a second BIGmack of a different colour (New BIGmacks come with four different colour interchangeable tops) which, when activated, says "Please remove the BIGmacks for five minutes" in a voice that is neutral in tone (such that the sound itself does not become a motivator) complete with a different symbolic label or sensory surface (or a lack of symbolic label or sensory surface) and both BIGmacks are placed within the reach of the Learner, we can now assess if the Learner activates the BIGmack which leads to a BEST reward more than the one which leads to their removal. Thus, as you can see, the activation of the original BIGmack leads to a reward while the activation of the other different BIGmack leads to their removal (and therefore no possibility of BEST) for a specified period of time. Initially, to assist the Learner in achieving success, the BEST BIGmack can be positioned on the preferred side of the Learner such that it is likely this is the one that will be activated. However, before moving to the next stage, it is important to swap the BIGmacks about such that, in wherever order they are positioned, the Learner still demonstrates that s/he can achieve success.

On success with two BIGmacks, step it up once more to three! Two of the BIGmacks lead to the removal of the setup (for a specified short time period) and only the original BIGmack obtains the BEST POLE. If the Learner learns to activate the BEST BIGmack no matter what position it occupies relative to the other two then there are a number of things that we might justifiably claim:

No, s/he's not doing that at all! S/he is just attracted to red BIGmacks and is going for the red one each time - no recall is taking place.

OK, that is a good point. So what should we do about that possibility? If it is known in advance that the Learner is attracted to the colour red then we should not use red as the BEST BIGmack but rather for the distractors! Alternatively, we can make all the BIGmacks red and just vary the attached symbols or the sensory surfaces.

We haven't got three BIGmacks!

It is Talksense's advice that every classroom should have at least three BIGmacks (AbleNet are not sponsoring me to say that! ) available for use. However, it does not have to be a BIGmack system, it can be any SGD (Speech Generating Device) or a device that has at least three cells (the other cells can remain blank). Alternatively, it is possible to use the Microsoft PowerPoint program on a touch sensitive screen although difficult to provide sensory surfaces by this methodology.

It's working too well: the Learner is asking for BEST all the time and we cannot support this!

Then remove the BIGmacks once the task has been completed and work on another area. You may also need to consider the use of 'limiting factors' was detailed on the fundamentals page of this website.

The BIGmacks can either have symbols on their surfaces or be presented with sensory switch caps. Only one BIGmack leads to the reward of a BEST POLE, the others either do something innocuous such as saying 'This BIGmack does nothing' or request their removal as stated above. The BIGmacks are positioned in front of the Learner. Beginning with a single BIGmack, the Learner will eventually activate it by accident. On so doing, the Learner is rewarded with the BEST. It is important that the reward follows the rules for BEST as outlined on the fundamentals page (follow link to go there).

My Learner is not interacting with the BIGmack even by accident.

For Learners that do not interact with the BIGmack it may be necessary for another member of staff to model the required behaviour such that the Learner can experience the staff member obtaining the BEST through the activation of a particular BIGmack. Should even that approach yield no result, the Learner can then be assisted to activate the BIGmack through hand-under-hand physical prompting.

What is it the the Learner loves? Is it sweets/candy? Is it a particular game, a TV programme, a particular person? In other words, what is the Best Ever Stimulating Thing for a particular individual? Let's start working with this BEST as the motivator.

POLE = Person Object Location Event

The BEST thing will be a POLE. POLE is an acronym for Person, Object, Location, or Event.

If we can place a tangible POLE at the end of a Learner action (For example: provide the Learner with a POLE as a result of a request using an Augmentative Communication system or activating a switch) then we have a way of moving forward. Not just any sort of POLE! What sort of POLE? Well, a BEST POLE of course.

Here are some ideas:

For those that can touch: Start with a single BIGmack (or equivalent device). Label it with an appropriate symbol or a Sensory Surface for the Learner's BEST POLE. By demonstrating, modelling, prompting, or even waiting for accidental access, allow the Learner to 'see' that the activation of the device leads to ( is always followed by) the provision of a BEST POLE. Hopefully, after a number of activations of the BIGmack, the Learner will begin to understand that his/her action (activating the BIGmack) results in a particularly favoured and rewarding event. However, even though a Learner may activate such a device repeatedly, it is difficult to establish intentionality: the Learner may continue to activate a device accidentally (for example) or just be exploring (and thus repeatedly activating) anything that has been placed in the Learner's reach without making any cognitive connection between his or her action and the rewards that seem to be occurring. How could we be more certain of some form of Learner cognizance?

If a baseline is taken in which the BIGmack (or equivalent) is utilised in a different manner (with a different sensory surface or symbol) such that it just plays a short piece of relatively uninteresting music (for example) then, when it is placed within the reach of the Learner, the number of activations (accidental and or purposeful) in a specified time period can recorded. Perhaps such practice might result in 4 activations in the first minute but this tails off afterwards such that it averages at less than one activation a minute. This is our baseline. If we now introduce the BIGmack resulting in the BEST POLE and this results in an increase in activations over time it would seem a reasonable assumption that the difference in Learner behaviour is as a result of some level of cognisance of the situation. As it is always good practice for staff to look for alternative explanations for changes in Learner behaviour, this situation should be no different. Perhaps the Learner is attracted to the BIGmack because it is a different colour (ensure that the same BIGmack is used). Perhaps the Learner is stimulated by the sensory surface that has been used and it is this that is causing the increased response level. How could we eliminate this possibility from our findings? We could swap the sensory surfaces used in the first experience (baseline) with the second and see if this provides similar results. While it is not good practice to use sensory surfaces it such a manner normally, in this instance it is justified. If the repeated baseline with the new sensory surface yields similar results to the original baseline then it cannot be the sensory surface itself that is responsible for the change in Learner response.

"Eliminate all other factors, and the one which remains must be the truth." (Sherlock Holmes, The sign of Four, Chapter 1, p. 92)

Once basic contingency awareness has been established and we have a Learner activating a BIGmack (or equivalent) to obtain a reward, it becomes necessary to step up the level of difficulty of the task very slightly, further to ascertain Learner cognisance. If we add a second BIGmack of a different colour (New BIGmacks come with four different colour interchangeable tops) which, when activated, says "Please remove the BIGmacks for five minutes" in a voice that is neutral in tone (such that the sound itself does not become a motivator) complete with a different symbolic label or sensory surface (or a lack of symbolic label or sensory surface) and both BIGmacks are placed within the reach of the Learner, we can now assess if the Learner activates the BIGmack which leads to a BEST reward more than the one which leads to their removal. Thus, as you can see, the activation of the original BIGmack leads to a reward while the activation of the other different BIGmack leads to their removal (and therefore no possibility of BEST) for a specified period of time. Initially, to assist the Learner in achieving success, the BEST BIGmack can be positioned on the preferred side of the Learner such that it is likely this is the one that will be activated. However, before moving to the next stage, it is important to swap the BIGmacks about such that, in wherever order they are positioned, the Learner still demonstrates that s/he can achieve success.

On success with two BIGmacks, step it up once more to three! Two of the BIGmacks lead to the removal of the setup (for a specified short time period) and only the original BIGmack obtains the BEST POLE. If the Learner learns to activate the BEST BIGmack no matter what position it occupies relative to the other two then there are a number of things that we might justifiably claim:

- the Learner is retaining and recalling the function of a specific BIGmack;

- the Learner is discriminating between the symbols or the sensory surfaces or the colours (if all the BIGmacks used were red then it must be either the sensory surface or the symbol used that is discriminated);

- the Learner is connecting a specific action (his/her activation of the device) with a particular environmental effect (his/her obtaining a BEST).

No, s/he's not doing that at all! S/he is just attracted to red BIGmacks and is going for the red one each time - no recall is taking place.

OK, that is a good point. So what should we do about that possibility? If it is known in advance that the Learner is attracted to the colour red then we should not use red as the BEST BIGmack but rather for the distractors! Alternatively, we can make all the BIGmacks red and just vary the attached symbols or the sensory surfaces.

We haven't got three BIGmacks!

It is Talksense's advice that every classroom should have at least three BIGmacks (AbleNet are not sponsoring me to say that! ) available for use. However, it does not have to be a BIGmack system, it can be any SGD (Speech Generating Device) or a device that has at least three cells (the other cells can remain blank). Alternatively, it is possible to use the Microsoft PowerPoint program on a touch sensitive screen although difficult to provide sensory surfaces by this methodology.

It's working too well: the Learner is asking for BEST all the time and we cannot support this!

Then remove the BIGmacks once the task has been completed and work on another area. You may also need to consider the use of 'limiting factors' was detailed on the fundamentals page of this website.

The BIGmacks can either have symbols on their surfaces or be presented with sensory switch caps. Only one BIGmack leads to the reward of a BEST POLE, the others either do something innocuous such as saying 'This BIGmack does nothing' or request their removal as stated above. The BIGmacks are positioned in front of the Learner. Beginning with a single BIGmack, the Learner will eventually activate it by accident. On so doing, the Learner is rewarded with the BEST. It is important that the reward follows the rules for BEST as outlined on the fundamentals page (follow link to go there).

My Learner is not interacting with the BIGmack even by accident.

For Learners that do not interact with the BIGmack it may be necessary for another member of staff to model the required behaviour such that the Learner can experience the staff member obtaining the BEST through the activation of a particular BIGmack. Should even that approach yield no result, the Learner can then be assisted to activate the BIGmack through hand-under-hand physical prompting.

|

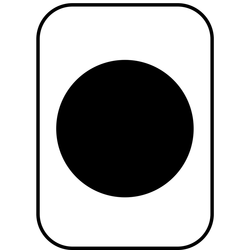

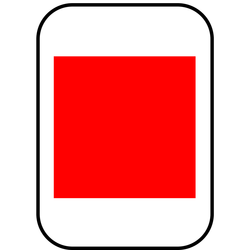

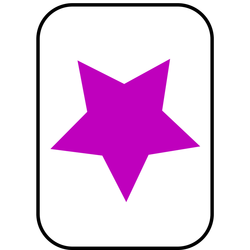

You might provide an intermediate stage in which the BIGmacks are presented but only one has a symbol attached as depicted in the illustration right. We are not trying to trick the Learner or make it difficult for him or her: we want the Learner to succeed and therefore you can provide as may intermediate stages as you think fit that will assist Learners on their way. Initially, for example, you might put the 'correct' BIGmack in the Learner's favoured position and then move it one place from there. You may also start with the Learner's preferred colour but this must be changed before the final stage of the procedure.

If a Learner can activate (on more than one occasion) the correct BIGmack by selecting a colour (and or a symbol) from three choices of colour (and or symbol) then it is party time! This a momentous achievement. Suppose all three BIGmacks are the same colour and all have symbols and yet the Learner still selects the reward (on more than one occasion) and with the BIGmacks in different relative position on each occasion - what can we now assert? The Learner must be discriminating between symbols! If a Learner can discriminate between symbols then the sky is the limit. Ensure you reward both yourself and your team for a job well done! |

For those that cannot touch (but can see): At least five cards may be prepared. Each of the cards depicts a different random shape which has no specific meaning. One of the cards is selected to represent the BEST. This is taught to the individual Learner through a combination of association and modelling (see below) until the Learner can select the card (without error) using a their own specific yes/no response in a 'blind' staff presentation.

In a blind presentation, the staff member concerned shuffles the cards and then presents them, one by one, face towards the Learner such that the Learner can see the card but the staff member cannot. In this way, there cannot be any unintentional cueing of the Learner as to when to respond. The Staff member continues to present the cards one by one, returning rejected cards to the back of the pack, until the Learner provides his/her 'yes response' to indicate this is the card selected. Only at this point can the staff member look at the face of the card at the front of the pack. If it is the card that has been selected as BEST then the reward must be provided. If it is any other card, then the opportunity to obtain BEST is withdrawn for a specified time (at least five minutes) while something else is done.

You're joking! That's way too advanced. My Learner will simply ignore the cards altogether.

Of course it is! That is why you have to begin with the single BEST card and teach the Learner it's meaning. Once you believe that the Learner has a grasp of the concept then you can add a second card into the mix and see if the Learner can select the one that represents the BEST. Selection of the other card should always lead to the withdrawal of the possibility of obtaining BEST for a specified

time period.

You're joking! My Learner cannot associate a card with a BEST. She'll just sit and rock.

You may be correct, but what are you doing in place of this? How do you know if you do not try? Each time you give the Learner the BEST for a whole term ensure that the card is presented just before. You could make the card shape tactile by drawing around the shape with a glue gun to raise its borders and then filling the shape with a sensory surface such as sand and glue and, when set, painting it the

appropriate colour. After a whole term you could try to ascertain if the Learner goes for that particular card when mixed in with a couple of plain cards. If that works then add a small dot to one of the plain cards and see if the Learner can still do it. Gradually increasing the distractors.

You're joking! My Learner cannot see.

In that case, why not try it with five distinct sounds (or with tactile tops to BIGmacks to make sensory surfaces as outlined earlier)? One of the sounds you have linked to the BEST.

Why does it have to be so abstract? Why can't I use real pictures of real things?

You can, at least for the BEST link. If you were to use pictures for the others then it might be claimed that the Learner was simply confused and is requesting the image on the card. If a Learner fails at the task as outline, it means nothing but if s/he repeatedly succeeds then it has a great deal of meaning!

My Learner loves stars so she always goes for that one even though it is incorrect.

What you're saying is that 'stars' are a BEST! Therefore, you should not be using a star image as one of the cards but one of the cards can lead to some starry reward!

You're joking! That's way too advanced. My Learner will simply ignore the cards altogether.

Of course it is! That is why you have to begin with the single BEST card and teach the Learner it's meaning. Once you believe that the Learner has a grasp of the concept then you can add a second card into the mix and see if the Learner can select the one that represents the BEST. Selection of the other card should always lead to the withdrawal of the possibility of obtaining BEST for a specified

time period.

You're joking! My Learner cannot associate a card with a BEST. She'll just sit and rock.

You may be correct, but what are you doing in place of this? How do you know if you do not try? Each time you give the Learner the BEST for a whole term ensure that the card is presented just before. You could make the card shape tactile by drawing around the shape with a glue gun to raise its borders and then filling the shape with a sensory surface such as sand and glue and, when set, painting it the

appropriate colour. After a whole term you could try to ascertain if the Learner goes for that particular card when mixed in with a couple of plain cards. If that works then add a small dot to one of the plain cards and see if the Learner can still do it. Gradually increasing the distractors.

You're joking! My Learner cannot see.

In that case, why not try it with five distinct sounds (or with tactile tops to BIGmacks to make sensory surfaces as outlined earlier)? One of the sounds you have linked to the BEST.

Why does it have to be so abstract? Why can't I use real pictures of real things?

You can, at least for the BEST link. If you were to use pictures for the others then it might be claimed that the Learner was simply confused and is requesting the image on the card. If a Learner fails at the task as outline, it means nothing but if s/he repeatedly succeeds then it has a great deal of meaning!

My Learner loves stars so she always goes for that one even though it is incorrect.

What you're saying is that 'stars' are a BEST! Therefore, you should not be using a star image as one of the cards but one of the cards can lead to some starry reward!

|

Not all our pupils have favourites.

Please do not say that! Yes, they do. It is just that with some individuals the BEST may be very hard to discover. I remember a school that told me they had thought that a particular Learner was not motivated by anything, until one day a group of musicians came to the school, and this young man was sat near to the tuba player and, every time he played, the young man's face lit up. It was a certain frequency of sounds that was motivating. Talk to Significant Others first - they are likely to know things that may be motivating or, at least, they may suggest a possible avenue of investigation. I am always concerned when a Learner is self harming as a form of stimulation. Trying to discover something that is more motivating than poking your own eyes or slapping your own face or biting yourself (and other such behaviours) is difficult (this is covered in greater detail in a following section). Thus don't say, 'This Learner is not motivated by anything' rather state more positively, 'We haven't yet discovered what motivates this Learner but we are still trying'. There will be something it just may not be obvious! |

What if a Learner's BEST is not age appropriate?

So what if it isn't? If it is a favourite, it is a place to start and an entry into their world. It is not that everything in the school day will be age inappropriate or that you will be treating them in an age inappropriate way - it is possible to use age inappropriate items in an age appropriate manner. Furthermore, the goal is not to remain with this item, the goal is to use the item as a springboard for moving forward. For me, providing it's ethical and it's a platform for development, then its an acceptable tool. Furthermore, the guiding factor should be 'Preference Not Deference' (see section on this below for further information). However, when the inspectors are around - I wouldn't recommend the use of age inappropriate things; some inspectors tend not to like them!

My Learner has no reaction to card presentation whatsoever even when paired with his BEST.

Try making the card more tactile. Use a glue gun to outline the shape and then infill it with some appropriate sensory surface. Present the card and assist the Learner to explore it before providing the BEST. Always provide the minimum amount of a BEST that will be still motivating to the Learner. Do this for an entire term! Try repeating the technique in the following term.

The staff are getting around the blind presentation by allowing the Learner to make multiple guesses until she gets it 'correct' and then rewarding this response. Is this wrong?

Yes! It may be OK for a short time in a teaching phase to help the Learner to see that only one specific card gets a reward but that should be a planned period of time. After this period, the staff must treat the selection of one of the other cards as a request (communicative act by the Learner) to stop the activity for (at least) five minutes and do something else instead.

My Learner's BEST is horse riding and we cannot provide that at any time.

In that instance, there are at least two things that you can do instead: select a second favourite (a second BEST) or, see if access to a short video of the Learner horse riding (or some other available connection) will act as a substitute.

The Learner gets it correct about 50% of the time but can have 'off periods'. What is the procedure in this eventuality?

The procedure is always consistent: if the Learner selects an incorrect card staff should treat it as though the Learner had said, "I'm fed up with this, let's stop for five minutes and do something else instead." If the Learner has had a seizure earlier or is known to be 'off' for whatever reason then perhaps you should not undertake the procedure, especially if it is likely that all choices at this time will not be correct. However, if you go ahead, an incorrect choice must always result in the termination of the procedure for a set period of time.

The Learner's BEST is chocolate. We can't keep feeding him chocolate all morning!

You need to review the Limiting Rules on the Fundamentals Page of this website. First, you need to establish what is the smallest amount of BEST that you can provide and yet still be motivating. Thus, it need not be a whole bar of chocolate as a reward but rather one square. Indeed, would a half of a square still suffice? What about a quarter? What about a quarter of a chocolate button? Also, once you have done this four times, perhaps it's time to stop and do something else instead. If the Learner has managed to get it correct four times then 'whoopee', what a success! Party time! Furthermore, that would equate to one whole chocolate button! That's not going to make him sick or ruin his appetite. Of course, if he chooses incorrectly, the process is terminated for a period of time and no reward is given. As such, it may take a whole session to get even a fraction of a chocolate button!

Stepping Up

So the Learner succeeds at one of the above techniques after quite a long period of time. What does that prove? And what then? Well, it shows that the Learning is capable of recalling - remembering a previous event and applying that knowledge to obtain another reward. Isn't that a form of contingency awareness? Maybe at a very basic level but isn't that where we are at?

What then? Ah! Now we leave an increasing time period between presentations of the technique: first, we may do it twice or more a day but then we limit it to once a day. Is the Learner still successful? OK. Now we present every two days, then three days, then once a week, once a month ... what does this tell us if the Learner is successful on each presentation? Suppose we left it an entire year and then we did it again with the Learner and s/he still got it correct?! Unlikely I know but not impossible. What we are assessing is the extent of a Learner's memory for a particular POLE.

You're crazy! My Learner will never manage any of this idea.

OK, I am crazy! If you do not believe that this has the slightest chance of succeeding no matter how it is modified for your circumstances then what about trying one of the other ideas on this page? Surely one of then has some merit for your Learner?

So what if it isn't? If it is a favourite, it is a place to start and an entry into their world. It is not that everything in the school day will be age inappropriate or that you will be treating them in an age inappropriate way - it is possible to use age inappropriate items in an age appropriate manner. Furthermore, the goal is not to remain with this item, the goal is to use the item as a springboard for moving forward. For me, providing it's ethical and it's a platform for development, then its an acceptable tool. Furthermore, the guiding factor should be 'Preference Not Deference' (see section on this below for further information). However, when the inspectors are around - I wouldn't recommend the use of age inappropriate things; some inspectors tend not to like them!

My Learner has no reaction to card presentation whatsoever even when paired with his BEST.

Try making the card more tactile. Use a glue gun to outline the shape and then infill it with some appropriate sensory surface. Present the card and assist the Learner to explore it before providing the BEST. Always provide the minimum amount of a BEST that will be still motivating to the Learner. Do this for an entire term! Try repeating the technique in the following term.

The staff are getting around the blind presentation by allowing the Learner to make multiple guesses until she gets it 'correct' and then rewarding this response. Is this wrong?

Yes! It may be OK for a short time in a teaching phase to help the Learner to see that only one specific card gets a reward but that should be a planned period of time. After this period, the staff must treat the selection of one of the other cards as a request (communicative act by the Learner) to stop the activity for (at least) five minutes and do something else instead.

My Learner's BEST is horse riding and we cannot provide that at any time.

In that instance, there are at least two things that you can do instead: select a second favourite (a second BEST) or, see if access to a short video of the Learner horse riding (or some other available connection) will act as a substitute.

The Learner gets it correct about 50% of the time but can have 'off periods'. What is the procedure in this eventuality?

The procedure is always consistent: if the Learner selects an incorrect card staff should treat it as though the Learner had said, "I'm fed up with this, let's stop for five minutes and do something else instead." If the Learner has had a seizure earlier or is known to be 'off' for whatever reason then perhaps you should not undertake the procedure, especially if it is likely that all choices at this time will not be correct. However, if you go ahead, an incorrect choice must always result in the termination of the procedure for a set period of time.

The Learner's BEST is chocolate. We can't keep feeding him chocolate all morning!

You need to review the Limiting Rules on the Fundamentals Page of this website. First, you need to establish what is the smallest amount of BEST that you can provide and yet still be motivating. Thus, it need not be a whole bar of chocolate as a reward but rather one square. Indeed, would a half of a square still suffice? What about a quarter? What about a quarter of a chocolate button? Also, once you have done this four times, perhaps it's time to stop and do something else instead. If the Learner has managed to get it correct four times then 'whoopee', what a success! Party time! Furthermore, that would equate to one whole chocolate button! That's not going to make him sick or ruin his appetite. Of course, if he chooses incorrectly, the process is terminated for a period of time and no reward is given. As such, it may take a whole session to get even a fraction of a chocolate button!

Stepping Up

So the Learner succeeds at one of the above techniques after quite a long period of time. What does that prove? And what then? Well, it shows that the Learning is capable of recalling - remembering a previous event and applying that knowledge to obtain another reward. Isn't that a form of contingency awareness? Maybe at a very basic level but isn't that where we are at?

What then? Ah! Now we leave an increasing time period between presentations of the technique: first, we may do it twice or more a day but then we limit it to once a day. Is the Learner still successful? OK. Now we present every two days, then three days, then once a week, once a month ... what does this tell us if the Learner is successful on each presentation? Suppose we left it an entire year and then we did it again with the Learner and s/he still got it correct?! Unlikely I know but not impossible. What we are assessing is the extent of a Learner's memory for a particular POLE.

You're crazy! My Learner will never manage any of this idea.

OK, I am crazy! If you do not believe that this has the slightest chance of succeeding no matter how it is modified for your circumstances then what about trying one of the other ideas on this page? Surely one of then has some merit for your Learner?

Preference Not Deference: a word on age-appropriateness

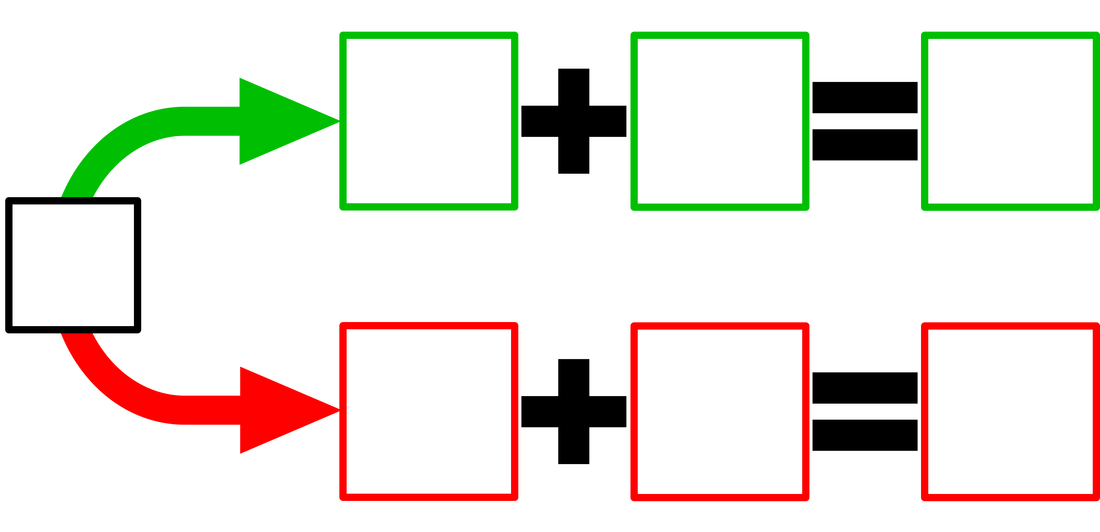

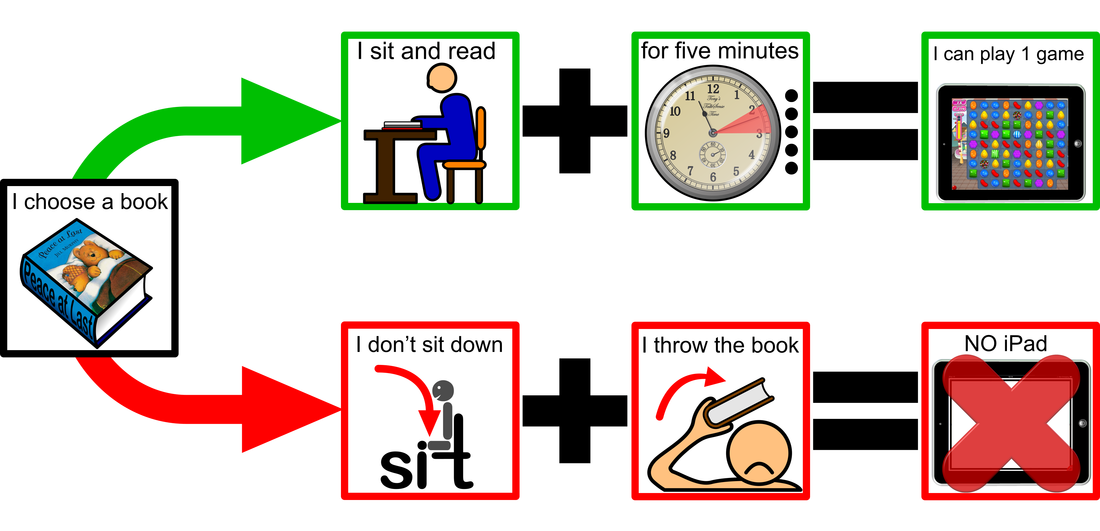

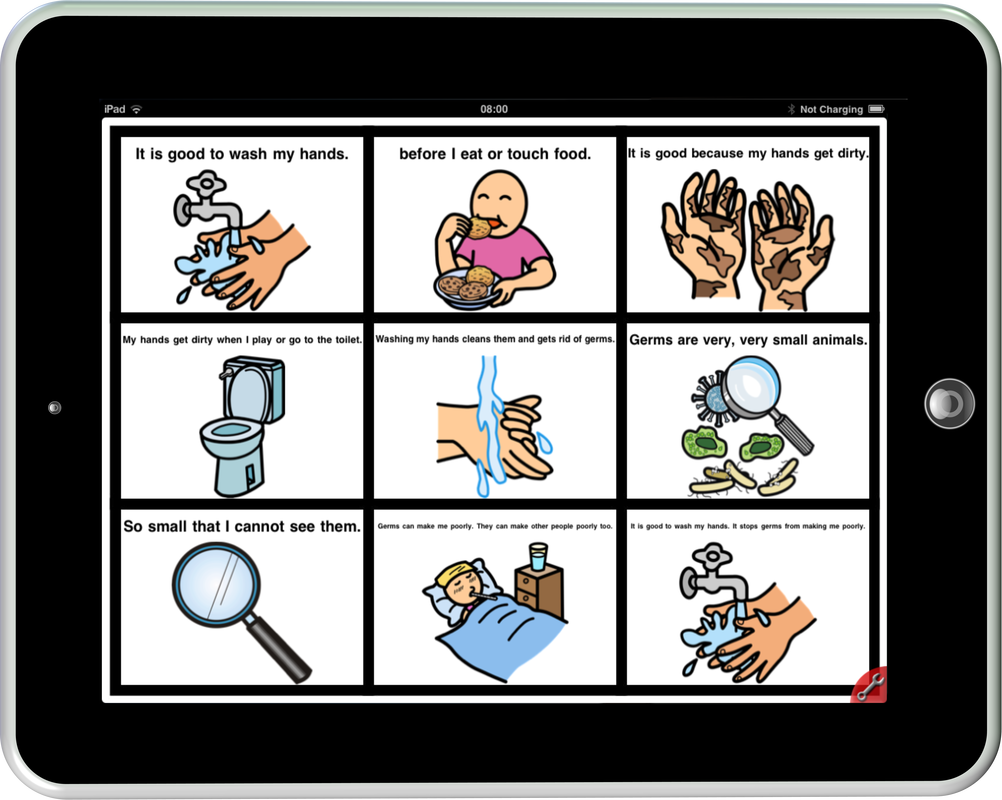

Click To Enlarge

Click To Enlarge

While age-appropriateness and developmental appropriateness are both important concerns, maybe we should concentrate more on what is ‘person-appropriate’" (Smith, 1996, page 79).

" ... stating that of course the chronological age of a person is one of the aspects of the person to be addressed in our education and care. However, we must not allow this issue to become paramount over the need to give regard to where the person is ‘at’ developmentally, psychologically, emotionally and communicatively. Additionally, people of whatever age can want or need physical stimulation and support." (Hewett, 2007, page 121)

"The storytelling has generated much discussion on what is age-appropriate material - for example, at what age, if any, do fairy tales become inappropriate?" (Birch et al., 2000, page 4)

"A principle operating in services throughout Australia, the UK, and the USA is that of age-appropriateness. The principle of age-appropriateness is widespread throughout government policy and non-government practice guidelines, but the exact meaning of the term is rarely defined. It is commonly assumed to mean activities and approaches commensurate with an individual’s chronological age. Dress, furnishing, object selection, and the style of interactions, are all supposed to be age-appropriate, according to many policies. However, when this principle is applied to people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities, I argue that instead of promoting a good life, the principle contributes to practices that compromise individuals’ health, well-being, quality of life, and their human rights." (Forster, 2010, page 129)

My guess is that everyone reading this webpage has something they like which is not particularly age appropriate. For example, I must admit to both watching and enjoying 'Sponge Bob Square Pants' from time to time. A friend (over 21) admits to taking a pink rabbit with her to bed. The issue is that we chose to like these things, they are our preferences. We did not defer to some other person's choice on our behalf (deference). Had I been taught Mandarin by using Sponge Bob when I had never seen him before or, had my friend been lectured on the curriculum in special education by use of a pink rabbit the, we might have questioned the (age) appropriateness. Actually, while working in Taiwan and trying to learn some Mandarin, I did watch children's cartoons because I thought that the language might be simpler for me to understand. However, again, it was by choice and my preference. There have been several studies and many papers concerning the use of dolls as therapy with older people with dementia that highlight the positive outcomes of such an approach and, which reflect and reinforce the notions made in the quote by Forster above (for a review of doll therapy see Turner and Shepherd 2010). However, the dolls are not imposed on the individuals. Indeed, Ellingford et al. (2007) argue that dolls should be introduced indirectly by leaving dolls in communal areas and on chairs, to allow for freedom of choice and free interaction.

In relation to Contingency Awareness practice therefore, items used should relate to Learner preference and Learners should not have to defer to another's choice that is not age appropriate. Thus, a reward provided to young adult might involve a doll (as in the cartoon) if that person has a preference for dolls. If dolls are this particular Learner's B.E.S.T. (Best Ever Stimulating Thing), their use in any contingency awareness program might help to captivate and engage the Learner in the process. B.E.S.T. practice, by definition, is highly motivating and may therefore be used within contingency awareness without fear of accusations of age inappropriateness (although some unenlightened individuals might claim otherwise!).

The Goal is Control

"Handicapped infants may begin to lose interest in a world that they do not expect to control" (Brinker & Lewis, 1982)

"Learned helplessness occurs when it is unclear to the learner that he or she is able to exert control over the environment.....For many learners, their social history has offered few opportunities to self-select desired objects, people, or activities. At meal times plates are prepared and distributed. Additional serving are provided automatically. Coats are handed out and doors opened when it is time to go. Thus, throughout the day, the caregivers do virtually everything for the learners. Initially, some learners may have attempted to self-select items of interest, but were actively encouraged not to do so." (Reichle, J. 1991 p.141)

"When children who are deafblind are young, and especially if they have additional difficulties, they may experience the world as much too large and complicated for them to exercise any control. Their experience may only be of having things done to them, not of doing things for themselves. They may have objects put in front of them to look at, but may not have any choice in the matter." (Wyman 2000 page 82)

"By providing people with PMLD the opportunities to exert control and actively participate we help to facilitate the development of contingency awareness; the knowledge that you are able to have some effect on the environment. ... If we are to prevent individuals either from resorting to self stimulatory behaviours or from withdrawing completely from the external world then it is essential that we ensure they are able to engage with their world in an active and meaningful way." (Hogg 2009. page 20)

While undoubtedly there are a plethora of goals for standard education, and many of these may have equal relevance to those experiencing PMLD, there is one particular goal that Talksense believes is a vital component of any curriculum designed to prepare Individuals Experiencing PMLD for a better quality of future life: that goal is 'control'.

"The provision of positive control experiences early in life will be a primary factor in helplessness immunization." (Sweeney, L. 1993)

"a high quality of life is one in which people receive individually tailored support to become full participants in the life of the community, develop skills and independence, be given appropriate choice and control over their lives, be treated with respect in a safe and secure environment”. (Emerson et al 1996)

"Empowerment occurs when control, or power, is passed to an individual or group. In rehabilitation, medicine, social work, psychology, education, and many allied disciplines, it is gradually becoming recognized that the healthiest and most effective individuals have personal control and make decisions for themselves with advice and input from others. The belief here is that, for best results overall, final decisions should be made by the individuals who are most closely affected by the decisions."

(Brown and Brown 2003 page 227)

"Students become empowered by taking control of their own learning." (Sutcliffe 1990 page 13)

"Good quality support is to do with giving people power." (Virginia Moffat 1996 page 37)

Generally speaking, the more independent people are and the less external control they receive from others, the more satisfied they are (higher quality of life) (See Legault 1992).Thus, a fundamental goal of all special education should be equipping Learners to live as independent a life as possible. This has long been recognised:

"... citizens with a mental retardation have a right to receive such individual habilitation as will give each of them a realistic opportunity to lead a more useful and meaningful life and to return to society." (Bannerman, Sheldon, Sherman, & Harchik 1990)

"even children with profound learning difficulties , given suitable conditions provided by modern technology, can make choices; in this case between sounds, voices, and rhymes provided on speakers. Moreover, they show enjoyment while so occupied and are motivated to further choice making. At the beginning of this chapter, the opinion was expressed that every step on the way to having more control over our lives is worth taking. In the case of these children, opportunity to exert control, however limited, appears to be leading to increased motivation and increasing self-regulation." (Beryl Smith 1994)(Page 5)

In order to meet this goal, staff within special education should be developing ways in which more and more control can be passed to Learners. Staff should rarely ever be doing it 'for' (there are some exceptions to this rule) and should hardly ever be doing it 'with' (again with some exceptions) but, rather, be facilitating individuals to do it for themselves. The goal of control therefore is one in which the Learner is at the centre of all that we do and the role of Significant Others is to help the Learner to take that control. An important aspect of taking control is an understanding that the things you do have an effect on both your environment and the people within the environment: in other words 'contingency awareness'.

While we may find a philosophical commitment to a particular idea or an approach fairly easy, often it is much more difficult to make that approach a reality. In observing any session involving Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties one should be constantly asking 'who is in control?' If the answer to that question, for the majority of the session, is other than the Learners involved then something is amiss. In observing any sessions involving Learners Experiencing PMLD look to see who is:

"Learned helplessness occurs when it is unclear to the learner that he or she is able to exert control over the environment.....For many learners, their social history has offered few opportunities to self-select desired objects, people, or activities. At meal times plates are prepared and distributed. Additional serving are provided automatically. Coats are handed out and doors opened when it is time to go. Thus, throughout the day, the caregivers do virtually everything for the learners. Initially, some learners may have attempted to self-select items of interest, but were actively encouraged not to do so." (Reichle, J. 1991 p.141)

"When children who are deafblind are young, and especially if they have additional difficulties, they may experience the world as much too large and complicated for them to exercise any control. Their experience may only be of having things done to them, not of doing things for themselves. They may have objects put in front of them to look at, but may not have any choice in the matter." (Wyman 2000 page 82)

"By providing people with PMLD the opportunities to exert control and actively participate we help to facilitate the development of contingency awareness; the knowledge that you are able to have some effect on the environment. ... If we are to prevent individuals either from resorting to self stimulatory behaviours or from withdrawing completely from the external world then it is essential that we ensure they are able to engage with their world in an active and meaningful way." (Hogg 2009. page 20)

While undoubtedly there are a plethora of goals for standard education, and many of these may have equal relevance to those experiencing PMLD, there is one particular goal that Talksense believes is a vital component of any curriculum designed to prepare Individuals Experiencing PMLD for a better quality of future life: that goal is 'control'.

"The provision of positive control experiences early in life will be a primary factor in helplessness immunization." (Sweeney, L. 1993)

"a high quality of life is one in which people receive individually tailored support to become full participants in the life of the community, develop skills and independence, be given appropriate choice and control over their lives, be treated with respect in a safe and secure environment”. (Emerson et al 1996)

"Empowerment occurs when control, or power, is passed to an individual or group. In rehabilitation, medicine, social work, psychology, education, and many allied disciplines, it is gradually becoming recognized that the healthiest and most effective individuals have personal control and make decisions for themselves with advice and input from others. The belief here is that, for best results overall, final decisions should be made by the individuals who are most closely affected by the decisions."

(Brown and Brown 2003 page 227)

"Students become empowered by taking control of their own learning." (Sutcliffe 1990 page 13)

"Good quality support is to do with giving people power." (Virginia Moffat 1996 page 37)

Generally speaking, the more independent people are and the less external control they receive from others, the more satisfied they are (higher quality of life) (See Legault 1992).Thus, a fundamental goal of all special education should be equipping Learners to live as independent a life as possible. This has long been recognised:

"... citizens with a mental retardation have a right to receive such individual habilitation as will give each of them a realistic opportunity to lead a more useful and meaningful life and to return to society." (Bannerman, Sheldon, Sherman, & Harchik 1990)

"even children with profound learning difficulties , given suitable conditions provided by modern technology, can make choices; in this case between sounds, voices, and rhymes provided on speakers. Moreover, they show enjoyment while so occupied and are motivated to further choice making. At the beginning of this chapter, the opinion was expressed that every step on the way to having more control over our lives is worth taking. In the case of these children, opportunity to exert control, however limited, appears to be leading to increased motivation and increasing self-regulation." (Beryl Smith 1994)(Page 5)

In order to meet this goal, staff within special education should be developing ways in which more and more control can be passed to Learners. Staff should rarely ever be doing it 'for' (there are some exceptions to this rule) and should hardly ever be doing it 'with' (again with some exceptions) but, rather, be facilitating individuals to do it for themselves. The goal of control therefore is one in which the Learner is at the centre of all that we do and the role of Significant Others is to help the Learner to take that control. An important aspect of taking control is an understanding that the things you do have an effect on both your environment and the people within the environment: in other words 'contingency awareness'.

While we may find a philosophical commitment to a particular idea or an approach fairly easy, often it is much more difficult to make that approach a reality. In observing any session involving Individuals Experiencing Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties one should be constantly asking 'who is in control?' If the answer to that question, for the majority of the session, is other than the Learners involved then something is amiss. In observing any sessions involving Learners Experiencing PMLD look to see who is:

- directing the action;

- operating any visual accompaniment (PowerPoint for example);

- activating the switches to create sound effects;

- operating the augmentative communication technology;

- making choices;

- mostly in control!

Accidental Awareness Award

During Piaget's Sensorimotor Stage of development which lasts from birth to approximately two years of age, the newborn is attempting to make some sense of the world that s/he has entered. The stage can be divided into six separate sub-stages through which each infant progress:

It is during the stages that involve circular reactions, the child gradually starts to make connections between his or her actions (body movements) and the things that happen in the environment. For example, a baby might accidentally hit a mobile in a cot and cause it to move or some music to play. If this pleases the child and it happens again, the child begins to understand that his/her movement is somehow linked to the reaction. The child will repeat approximations of the movement until s/he can consistently activate the mobile in a desired manner.

Our Learners, likewise may not understand they have an ability to control a favourite event (music playing, lights coming on, fan blowing). While they may show pleasurable responses when these events occur, their understanding of why they occur may be extremely limited (even non-existent). However, if we can:

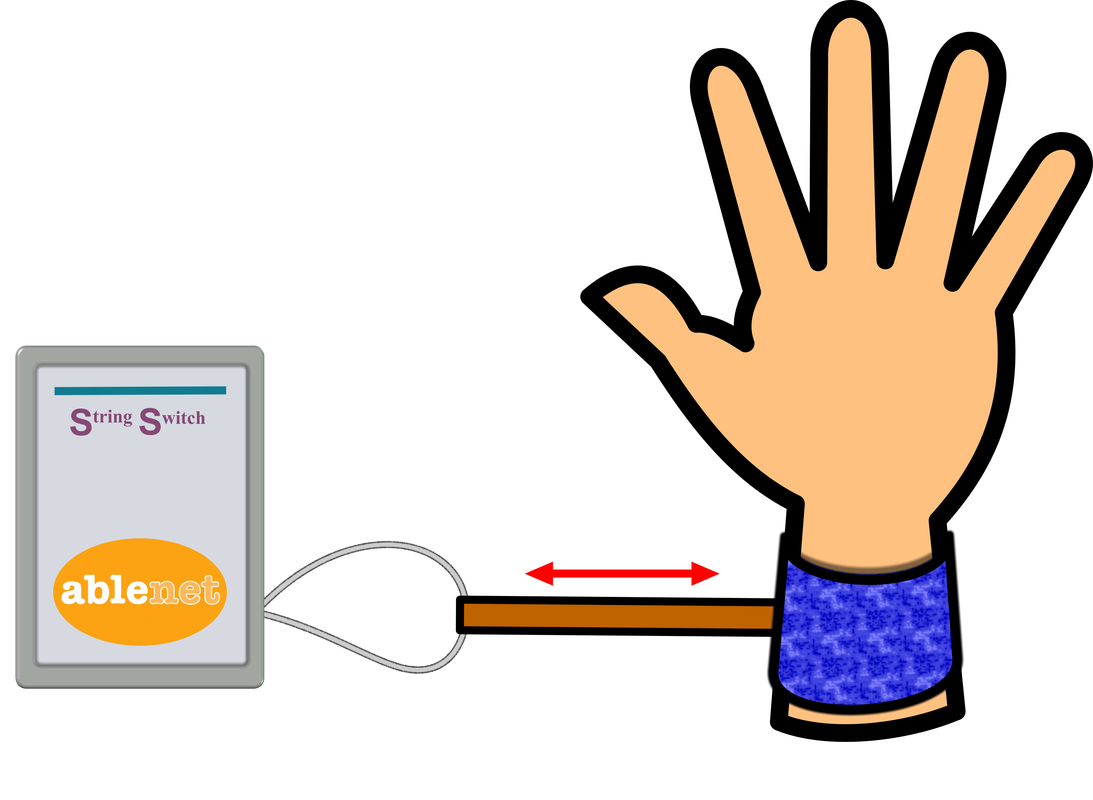

AbleNet's String Switch is but one tool that can be used to promote accidental awareness of cause and effect. It comprises a small plastic box from which protrudes a short loop of string. Pulling on the string causes a switch activation. Only a very slight force is required to pull the string to activate the switch. While the majority of other switches are directional, the String Switch is not. For example, to operate a Jelly Bean type of switch, a Learner has to target the switch and move his hand (or other body part) to the switch. However, by setting up the String Switch (for example, as illustrated below) it does not matter in which direction the Learner's arm moves (or other body part) as sufficient movement in any direction in any plane will activate the switch. What is sufficient movement? That can be set by the Significant Other involved! By attaching an elastic band (or conjoined elastic bands) to the string at one end and to a wrist band at the other, it is possible to vary the length of travel of the Learner's arm/hand before a switch activation is made. Thus, if the Learner is continually moving his/her arm a little, it would be possible to allow for this without any operation of the switch but, when the arm/hand moves slightly more beyond this allowable range the switch is activated! If the switch is plugged into a BEST (Best Ever Stimulating Thing: See section above) an accidental movement of the Learner's arm can cause a BEST to occur. As the BEST, by definition, is highly motivational for the Learner, it is likely that the Learner will want that to happen again. With repeated accidental activations of BEST over a period of time, the Learner may come to realise that s/he is in control of it through a movement of his or her arm. Activation of the switch should therefore increase over time from the ('accidental') baseline. The use of elastic bands as a joining agent between the switch and the Learner prevents a jarring sensation which might occur when the Learner's arm (or other body part) reaches the maximum distance of travel allowed by an alternative medium. The elastic also affords some protection to the switch itself. Please note that elastic bands and wrist bands are not supplied with the String Switch at purchase.

- Reflex (0 - 1 month);

- Primary Circular Reactions (1 - 4 months);

- Secondary Circular Reactions (4 - 8 months);

- Coordination of Reactions (8 - 12 months);

- Tertiary Circular Reactions (12 - 18 months);

- Early representational Thought (18- 24 months).

It is during the stages that involve circular reactions, the child gradually starts to make connections between his or her actions (body movements) and the things that happen in the environment. For example, a baby might accidentally hit a mobile in a cot and cause it to move or some music to play. If this pleases the child and it happens again, the child begins to understand that his/her movement is somehow linked to the reaction. The child will repeat approximations of the movement until s/he can consistently activate the mobile in a desired manner.

Our Learners, likewise may not understand they have an ability to control a favourite event (music playing, lights coming on, fan blowing). While they may show pleasurable responses when these events occur, their understanding of why they occur may be extremely limited (even non-existent). However, if we can:

- put a favourite event at the end of a switching system;

- position the switching system so that it is likely to be activated by a Learner by accident from time to time;

- establish a baseline measurement of how many times the event is triggered by accident alone in the first time period (few minutes);

- leave the Learner with the switching system;

- check to see if the number of events increases over time.

AbleNet's String Switch is but one tool that can be used to promote accidental awareness of cause and effect. It comprises a small plastic box from which protrudes a short loop of string. Pulling on the string causes a switch activation. Only a very slight force is required to pull the string to activate the switch. While the majority of other switches are directional, the String Switch is not. For example, to operate a Jelly Bean type of switch, a Learner has to target the switch and move his hand (or other body part) to the switch. However, by setting up the String Switch (for example, as illustrated below) it does not matter in which direction the Learner's arm moves (or other body part) as sufficient movement in any direction in any plane will activate the switch. What is sufficient movement? That can be set by the Significant Other involved! By attaching an elastic band (or conjoined elastic bands) to the string at one end and to a wrist band at the other, it is possible to vary the length of travel of the Learner's arm/hand before a switch activation is made. Thus, if the Learner is continually moving his/her arm a little, it would be possible to allow for this without any operation of the switch but, when the arm/hand moves slightly more beyond this allowable range the switch is activated! If the switch is plugged into a BEST (Best Ever Stimulating Thing: See section above) an accidental movement of the Learner's arm can cause a BEST to occur. As the BEST, by definition, is highly motivational for the Learner, it is likely that the Learner will want that to happen again. With repeated accidental activations of BEST over a period of time, the Learner may come to realise that s/he is in control of it through a movement of his or her arm. Activation of the switch should therefore increase over time from the ('accidental') baseline. The use of elastic bands as a joining agent between the switch and the Learner prevents a jarring sensation which might occur when the Learner's arm (or other body part) reaches the maximum distance of travel allowed by an alternative medium. The elastic also affords some protection to the switch itself. Please note that elastic bands and wrist bands are not supplied with the String Switch at purchase.

Learners exhibiting behaviours that staff may find challenging involving some form of self harm may also be assisted by this method. For example, a Learner self stimulated by eye poking, staff may splint arms in an attempt to reduce the behaviour (or strap Learner arms to wheelchairs). While such techniques do serve to reduce the instances of self harm they do little to eliminate its cause and, once the splints are removed, the behaviour returns. Why is this Learner poking himself in the eye? He must find it rewarding in some way. Either he gains attention from staff or he finds the sensation more stimulating than his environment. Suppose we could provide a means for this Learner to gain the same effect with less harmful consequences and, at the same time, develop contingency awareness? If we:

The elastic band does not have to be attached to a wrist band, it could be attached to a head band or be operated by a leg/ankle or some other body movement. Furthermore, the string does not have to be attached to a body part at all: It might be attached to a favourite object such that, as the Learner reaches for the object and attempts to take it, this action pulls on the string which, in turn. activates the switch. In the past, I have suspended a soft sponge ball from a string switch which dangled down in front of a Learner such that he could operate a device by grasping the ball and pulling down as in a light cord in a bathroom.

The string switch might be used in such a way that it does not have to be operated by the Learner at all! For example, it would be possible to set up a toy car (or other moving toy or object) under a Learner's control. The Learner would be tasked to move the car into some form of barrier. The string switch could then be attached to the barrier such that, when the car moved the barrier, the barrier operated the string switch which, in turn provided a reward for the Learner!

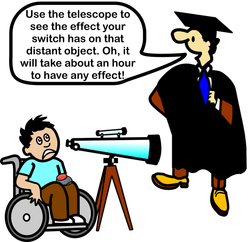

I like the idea of the string switch and the fan but what do we do when this has been established? How do we progress from here?

That is a good question! First you can try reducing the stimulation to see if you can get similar results from less input. For example, you can turn the fan setting down to a lesser speed and keep reducing its speed over several days if the results are positive. You can also start moving the fan further and further away from the Learner's face such that over time less reward is acceptable for a particular behaviour. Also, once established, you can trial other forms of stimulation via the switch to demonstrate to the Learner that he can control his environment through his actions.

We can't have him attached to a fan all the time. What do we do in other areas?

As suggested in the response to the previous question the fan serves more than one purpose: if successful, it can also lead to the use of a natural Learner movement in the control of items in the environment. For example, it might be used to turn on music in the Learner's bedroom. The fan is a means to an end. The possibilities are much greater.

- place a large fan directly in front of the Learner's face and set it to a high speed (the fan must be protected by a sturdy metal cage such that the Learner cannot put his fingers into the blades as they turn);

- attach the fan to a PowerLink (or equivalent system);

- add a wrist band to the Learner's wrist attached by a rubber band and a length of string to a string switch such that as the Learner moves his arm/hand upwards to poke his eyes the string switch is activated before his hand can reach his eye;

- attach the string switch to the PowerLink such that it operates whatever item is attached;

The elastic band does not have to be attached to a wrist band, it could be attached to a head band or be operated by a leg/ankle or some other body movement. Furthermore, the string does not have to be attached to a body part at all: It might be attached to a favourite object such that, as the Learner reaches for the object and attempts to take it, this action pulls on the string which, in turn. activates the switch. In the past, I have suspended a soft sponge ball from a string switch which dangled down in front of a Learner such that he could operate a device by grasping the ball and pulling down as in a light cord in a bathroom.

The string switch might be used in such a way that it does not have to be operated by the Learner at all! For example, it would be possible to set up a toy car (or other moving toy or object) under a Learner's control. The Learner would be tasked to move the car into some form of barrier. The string switch could then be attached to the barrier such that, when the car moved the barrier, the barrier operated the string switch which, in turn provided a reward for the Learner!

I like the idea of the string switch and the fan but what do we do when this has been established? How do we progress from here?

That is a good question! First you can try reducing the stimulation to see if you can get similar results from less input. For example, you can turn the fan setting down to a lesser speed and keep reducing its speed over several days if the results are positive. You can also start moving the fan further and further away from the Learner's face such that over time less reward is acceptable for a particular behaviour. Also, once established, you can trial other forms of stimulation via the switch to demonstrate to the Learner that he can control his environment through his actions.

We can't have him attached to a fan all the time. What do we do in other areas?

As suggested in the response to the previous question the fan serves more than one purpose: if successful, it can also lead to the use of a natural Learner movement in the control of items in the environment. For example, it might be used to turn on music in the Learner's bedroom. The fan is a means to an end. The possibilities are much greater.

Everyone's a Winner

Teaching an individual contingency awareness does not just bring benefits for the Learner but also for the the people involved in the teaching:

"Findings support the hypothesis that response-contingent learning, and a child’s recognition of his or her capabilities (contingency detection and awareness), evoked a sense of child pleasure and enjoyment, and that a caregiver providing a child learning opportunities that resulted in increased child competence derived gratification from both the child’s and her own efforts."

(Raab, Dunst, Wilson, & Parkey 2009)

Thus, the Learner not only acquires the skills but such learning also brings pleasure and enjoyment to the Learner and the Significant Others involved. The pleasure a Learner gains from becoming 'contingency aware' has also been reported by others:

"he reports pupils make clear gestures and indicate through smiles and laughs they are aware it is them who are creating and affecting the sounds they hear." (Williams, Petersson, Brooks 2006)

(see also Ellis 1995)

"Findings support the hypothesis that response-contingent learning, and a child’s recognition of his or her capabilities (contingency detection and awareness), evoked a sense of child pleasure and enjoyment, and that a caregiver providing a child learning opportunities that resulted in increased child competence derived gratification from both the child’s and her own efforts."

(Raab, Dunst, Wilson, & Parkey 2009)

Thus, the Learner not only acquires the skills but such learning also brings pleasure and enjoyment to the Learner and the Significant Others involved. The pleasure a Learner gains from becoming 'contingency aware' has also been reported by others:

"he reports pupils make clear gestures and indicate through smiles and laughs they are aware it is them who are creating and affecting the sounds they hear." (Williams, Petersson, Brooks 2006)

(see also Ellis 1995)

Adversity Bringeth Cognition

Individuals Experiencing PMLD often have a strong startle reflex:

Let us suppose that Johnny has a switch attached to a POLE event (Person Object Location Event) that causes him to startle as stated above. The first time he hits the switch he startles. The second time he hits the switch he startles. The third time, however, there is an obvious reduction in Johnny's reaction and, by the fourth switch activation, there is no discernible startle reaction whatsoever. What does this tell us? What can we state about Johnny after observing his behaviour? Surely, it must, at least, suggest that Johnny has become accustomed to the POLE action caused by activating the switch. If this is the case, how has he become accustomed? It is not by magic! He must be anticipating what is about to happen and if he is anticipating then:

Continuing with the example of Johnny. Let us suppose he interacts with the switch and the toy for ten minutes during the session, after which the switch and toy are removed so that he might participate in some other activity. Approximately 30 minutes later, the switch and the toy are re-presented and Johnny begins to activate the switch once more. The first time he startles. However, unlike his first experience, the startle response is absent on his second switch activation. Furthermore, when Johnny returns to the classroom after lunch and works with the switch and the toy for a third session, there is no startle response at all. What can we now begin to assume?

Suppose Johnny works with toy the following day still with no adverse reaction. Then, we let two days pass before we reintroduce the same toy to Johnny: still no adverse reaction. Indeed, it seems to require a week of absence from the toy before the startle reflex returns as strong as it was initially. Does this not suggest an observable means of establishing the retention of specific contingency awareness for an Individual experiencing PMLD over a period of time? Not only can we claim that Johnny is making a link but he is remembering it and we can also measure for how long!

Of course, we are not setting out to deliberately startle any individual (nor is this being recommended) but, if it happens in the course of a daily event (and it is my experience at least that it occasionally does), then we can turn the situation to our advantage as well as helping Johnny to work with a toy which we believe he will ultimately find pleasurable and also has educational merit.

- Johnny hits a switch and a toy rocket launcher makes a bang or a stationary toy suddenly springs into life;

- Johnny startles and his face shows signs of upset;

- Staff notice Johnny's state and remove the offending toy stating that he had an adverse reaction and they will find him something which will not scare him so.

Let us suppose that Johnny has a switch attached to a POLE event (Person Object Location Event) that causes him to startle as stated above. The first time he hits the switch he startles. The second time he hits the switch he startles. The third time, however, there is an obvious reduction in Johnny's reaction and, by the fourth switch activation, there is no discernible startle reaction whatsoever. What does this tell us? What can we state about Johnny after observing his behaviour? Surely, it must, at least, suggest that Johnny has become accustomed to the POLE action caused by activating the switch. If this is the case, how has he become accustomed? It is not by magic! He must be anticipating what is about to happen and if he is anticipating then:

- he must have linked the switch to the event (cause and effect - see cause and effect this page);

- he must be remembering previously encountered experiences.

Continuing with the example of Johnny. Let us suppose he interacts with the switch and the toy for ten minutes during the session, after which the switch and toy are removed so that he might participate in some other activity. Approximately 30 minutes later, the switch and the toy are re-presented and Johnny begins to activate the switch once more. The first time he startles. However, unlike his first experience, the startle response is absent on his second switch activation. Furthermore, when Johnny returns to the classroom after lunch and works with the switch and the toy for a third session, there is no startle response at all. What can we now begin to assume?