Preventing Poor and Promoting Positive Practice in Special Education

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge

Sigelman et al (1982) considered some issues involved in interviewing people experiencing a Learning Difficulty. They evaluated a range different questioning techniques according to the extent to which:

"Communication is a two-way process, and the ability of mentally retarded persons to respond to a question might depend heavily on the form, clarity, and salience of the question. Thus we sought not only to understand the limits of retarded people's abilities to participate in interviews but also to identify more and less effective ways of asking questions of them." (Sigelman et al 1983 page 1.3)

I am often asked to observe and feedback on sessions within special education. I have been lucky enough to have done this in many different countries. I dislike intensely criticising any staff member who is obviously trying to do a good job; I see my role to assist the person address any issues in their practice without questioning their ability or undermining their confidence. While there is generally no one 'correct' approach and I witness only a very few examples of really poor practice, what I generally note are several issues that crop up again and again which fall under the broad category of 'assumptions of understanding'. These issues revolve around a staff notion that Learners are gaining from specific experiences on scant evidence. For example, a staff member,

Sigelman et al (1983 page 2.3) appear to believe (based on Baroff's 1974 work) that the use of questioning techniques of any kind are inappropriate for Learners who have a mental age of below four years of age:

"The ability to respond to questions is not evident prior to mental age four or five.Therefore, efforts directed at interviewing retarded persons below this mental age may be inadvisable and of limited value." (Sigelman et al 1983)

As those experiencing a significant learning difficulty might, indeed, be classified in such a manner, should the staff in specialist educational establishments simply give up? Should they simply teach but refrain from any inquiry as to the efficacy of their instruction? Of course not! Seligman et al state that it may be inadvisable, not that it definitely is. Indeed, more than 30 years on from this work, I think we can safely say that we know a thing or two more about how this population works and how to work with them.

This webpage covers issues involved in the practice of teaching and learning within special education provision using evidence based research to reinforce any claims that are made. It offers:

At the end of the page there is a comprehensive bibliography and references session and a section in which you may have your say on any of the issues raised.

As nearly all the pages on this website are updated from time to time I am now including a date counter such that it is possible to see if there have been any changes since a previous visit.

This page was last updated on 19th May 2014

- Learners could provide answers;

- Learner answers agreed with parallel responses given by Significant Others;

- Learner answers were free of systematic response bias.

- open questions (those that required more than a yes/no response) were unanswerable by many of those in the study;

- supplementing open questions with clarifying examples and probes for additional information only exacerbated response bias.

- yes-no checklists led to greater responsiveness but introduced serious acquiescence bias (the tendency to answer 'yes' to all questions);

- multiple choice questions, particularly those with accompanying pictures, produced better results from a high proportions of Learners.

"Communication is a two-way process, and the ability of mentally retarded persons to respond to a question might depend heavily on the form, clarity, and salience of the question. Thus we sought not only to understand the limits of retarded people's abilities to participate in interviews but also to identify more and less effective ways of asking questions of them." (Sigelman et al 1983 page 1.3)

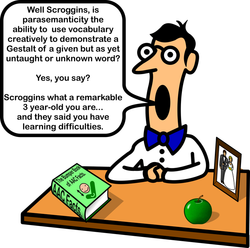

I am often asked to observe and feedback on sessions within special education. I have been lucky enough to have done this in many different countries. I dislike intensely criticising any staff member who is obviously trying to do a good job; I see my role to assist the person address any issues in their practice without questioning their ability or undermining their confidence. While there is generally no one 'correct' approach and I witness only a very few examples of really poor practice, what I generally note are several issues that crop up again and again which fall under the broad category of 'assumptions of understanding'. These issues revolve around a staff notion that Learners are gaining from specific experiences on scant evidence. For example, a staff member,

- asks a yes no question (closed question format) to which the Learner responds 'yes'. Staff praise the Learner and move on;

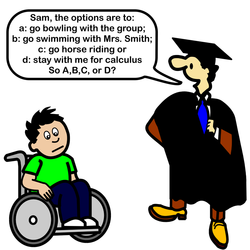

- provides a verbal listing of alternatives and asks a learner to choose;

- holds up two objects and asks a Learner to choose the one that s/he wants. The Learner indicates one item;

- holds up two symbol or photographic cards and, as above, asks the Learner to indicate a choice.

- asks referential type of questions with no Learner response;

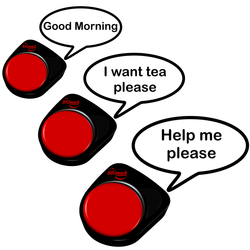

- takes a BIGmack and moves around a group saying and signing 'good morning' to each member one at a time permitting the group members to respond by activating the simple AAC system.

Sigelman et al (1983 page 2.3) appear to believe (based on Baroff's 1974 work) that the use of questioning techniques of any kind are inappropriate for Learners who have a mental age of below four years of age:

"The ability to respond to questions is not evident prior to mental age four or five.Therefore, efforts directed at interviewing retarded persons below this mental age may be inadvisable and of limited value." (Sigelman et al 1983)

As those experiencing a significant learning difficulty might, indeed, be classified in such a manner, should the staff in specialist educational establishments simply give up? Should they simply teach but refrain from any inquiry as to the efficacy of their instruction? Of course not! Seligman et al state that it may be inadvisable, not that it definitely is. Indeed, more than 30 years on from this work, I think we can safely say that we know a thing or two more about how this population works and how to work with them.

This webpage covers issues involved in the practice of teaching and learning within special education provision using evidence based research to reinforce any claims that are made. It offers:

- suggested checks to avoid potential pitfalls;

- alternate positive practices.

At the end of the page there is a comprehensive bibliography and references session and a section in which you may have your say on any of the issues raised.

As nearly all the pages on this website are updated from time to time I am now including a date counter such that it is possible to see if there have been any changes since a previous visit.

This page was last updated on 19th May 2014

PAGE IN DEVELOPMENT

This page is in development. That means it is incomplete. While you are free to investigate what is already here please note that it is:

When the page is nearing completion I will remove this warning.

- incomplete;

- liable to extensive changes and updates;

- out of order: I may move things around;

- likely to contain typos and other errors.

When the page is nearing completion I will remove this warning.

1. Assumptions of Understanding

click to enlarge

click to enlarge

"Mentally retarded respondents may tend to report attitudes and behaviors which they believe will meet approval, especially if they perceive the interviewer as having power."

(Sigelman et al 1983)

"A second strategy for evaluation of response validity has been to ask questions to which the correct answer is known. This technique reduces the ambiguity inherent in the first 7.1 strategy. If, in response to such questions, mentally retarded persons are able to provide accurate information, we have sound evidence of their ability to give accurate responses to at least some interview questions." (Sigelman et al 1983 page 7.1)

"These data regarding the validity of the responses of mentally retarded persons are not encouraging. It is clear that information drawn from interviews with retarded persons must be evaluated critically. Children's responses frequently fail to correspond closely to the responses of their parents. It is particularly notable that this lack of agreement exists for some simple questions regarding factual information which should be readily available to most persons." (Sigelman et al 1983 page 7.11)

"The verbal method is likely to be least useful of all the possible formats for individuals with communication deficits, even if the individual has a vocal repertoire. Nonetheless, parents, teachers, and other caregivers frequently offer verbal choices to individuals with developmental disabilities who have vocal skills, apparently overlooking this important limitation. Even individuals with a vocal repertoire have some degree of communication difficulty that affects their ability to accurately understand or respond to verbal statements or questions regarding their preferences" (Vorndran 2005 page 10)

We may believe, if we ask a simple and straightforward question and get a simple and straightforward answer then we can assume understanding on the part of the Learner. However, in their 1983 study, Sigelman et al listed at least 7 reasons why this assumption might be problematic:

A. The wording of questions can influence the answer :

The structure of a question can influence the answer provided by a person experiencing a Learning difficulty. It is thus difficult to establish validity in an answer given to almost any seemingly straightforward question. Even small changes in question wording can have major effects on responses:

"We found that retarded persons were far more likely to say certain unacceptable behaviors (e.g., hitting others) were prohibited if the question was phrased, "Are you allowed to. than if the question was phrased "is it against the rules to. We even found, thanks to a typographical error in the interview schedule, that responses to "Who decides what chores you do?" and "Who decides what chores to do?" differed. "

(Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.41)

The same research found that responses to oppositely worded questions (which should produce different responses as a person cannot logically agree with one while, at the same time, be in agreement with the other) is also problematic with Individuals experiencing .Learning Difficulties often providing contradictory answers. Sigelman et al (op cit) also state that questions including examples may also make a Learner more likely to use those examples in his/her answer even if they are not what s/he actually does or thinks:

"if a question calling for an enumeration of activities in a given category (e.g., sports) mentions examples (e.g., football and baseball), retarded persons will be more likely than usual to name the very activities used as examples."

(Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.40)

Indeed, there were so many issues emanating form the structure of questions that they went on to say:

"We can only recommend that there be extensive piloting of interview schedules to determine whether respondents understand and, if so, how they interpret alternatively phrased questions." (Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.41)

B. Using probing techniques to elicit further information is problematic:

"When interviewees are asked open-ended questions calling for an enumeration of activities, many cannot respond at all and those who can are likely to name very few activities. On the other hand, the strategy of probing indefinitely with "What else?" solves that problem but creates another that is more serious: over-reporting of activities in response to the implied demand to do so to the extent that answers lose validity. "

(Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.41)

"If one interviewer chooses to follow up an unclear answer with a simple yes-no questions while another chooses to use an either-or question to

pursue the matter, we can predict that the two interviewers are likely to get different answers. This is by no means a trivial issue, for our experience suggests that no matter how well original questions are designed, there is likely to be some need to follow-up or clarify vague or confusing answers." (Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.41)

C. Multiple choice questions with qualitative responses are typically unreliable:

"Multiple choice questions that call for responses along a quantitative dimension (e.g., a lot, some, not much, and not at all) appear to be generally useless as sources of information. They are relatively difficult for retarded persons to answer, in the first place; but more importantly, respondents appear to have difficulty attaching consistent meanings to such terms."

(Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.41)

"Unfortunately, we have no constructive advice for interviewers who seek quantitative information about such things as extent of involvement in various activities." (Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.44)

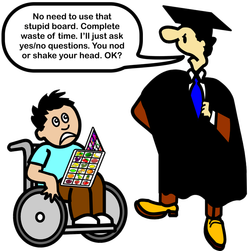

D. Closed Question format responses may be misleading:

Even before reading this research, I have been saying for many years that the use of the closed question format is problematic withing special education. This is covered further below in the section on closed questions. While such questions are quick and easy to use and seemingly to answer, Sigelman et al show throughout their 1983 study that this view is mistaken:

"Yes-no questions, despite the fact that they are easily answered by most retarded persons, are not useful in interviewing retarded persons. While this statement may seem strong, we have devoted more attention to yes-no questions than to any other format and we have found, with few exceptions, that retarded persons are highly likely to answer "yes" regardless of question content. "

(Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.44)

E. Open ended questions prove more difficult for people experiencing learning difficulties:

"Open-ended questions have one overriding limitation: they cannot be answered by very many retarded persons. As a result, they are not very useful at all in interviewing more severely retarded persons. " (Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.44)

However, they did find that open-ended questions which required a single response (for example: What drink did you have at break time?) were relatively well answered. Thus, question requiring a single word open-ended response is likely to be a more sound approach than the use of the closed question format.

So to overcome problems in checking for understanding what question forms are likely to be the more reliable?

"Multiple choice questions offering discrete response alternatives, however, may have promise. In asking respondents what type of dwelling they lived in and how they got to school, we found that questions of this type worked well; better than open-ended questions on the same topics, for they enhanced responsiveness without sacrificing validity."

(Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.44)

Even though they suggest this as a better form of questioning, they do warn of the the dangers of response biases (see later this page). It should also be noted that Sigelman et al go on to report that the use of picture card based versions of the above may not be that advantageous :

"We are not confident that pictures provide enough of an advantage to warrant the effort involved in producing them."

However, when working with those who cannot respond to a question verbally, there is a definitely advantage in this approach and thuse it is one that I support in seeming contradiction to the above quote.

"Of all the question formats we have tested, either-or questions, particularly those accompanied by pictorial representations of the alternatives, appear to be the best way of optimizing responsiveness and response validity."

(Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.45)

However, it should not be assumed that, even in using this methodology, it cannot be affected by a positional bias (see section below) and therefore this should always be kept in mind whilst undertaking the technique.

While Sigelman et al do not state this explicitly, it might be inferred that the use of real objects as choice items in an array (as opposed to pictures or symbols) would be the easiest method with which Learners could cope.

(Sigelman et al 1983)

"A second strategy for evaluation of response validity has been to ask questions to which the correct answer is known. This technique reduces the ambiguity inherent in the first 7.1 strategy. If, in response to such questions, mentally retarded persons are able to provide accurate information, we have sound evidence of their ability to give accurate responses to at least some interview questions." (Sigelman et al 1983 page 7.1)

"These data regarding the validity of the responses of mentally retarded persons are not encouraging. It is clear that information drawn from interviews with retarded persons must be evaluated critically. Children's responses frequently fail to correspond closely to the responses of their parents. It is particularly notable that this lack of agreement exists for some simple questions regarding factual information which should be readily available to most persons." (Sigelman et al 1983 page 7.11)

"The verbal method is likely to be least useful of all the possible formats for individuals with communication deficits, even if the individual has a vocal repertoire. Nonetheless, parents, teachers, and other caregivers frequently offer verbal choices to individuals with developmental disabilities who have vocal skills, apparently overlooking this important limitation. Even individuals with a vocal repertoire have some degree of communication difficulty that affects their ability to accurately understand or respond to verbal statements or questions regarding their preferences" (Vorndran 2005 page 10)

We may believe, if we ask a simple and straightforward question and get a simple and straightforward answer then we can assume understanding on the part of the Learner. However, in their 1983 study, Sigelman et al listed at least 7 reasons why this assumption might be problematic:

A. The wording of questions can influence the answer :

The structure of a question can influence the answer provided by a person experiencing a Learning difficulty. It is thus difficult to establish validity in an answer given to almost any seemingly straightforward question. Even small changes in question wording can have major effects on responses:

"We found that retarded persons were far more likely to say certain unacceptable behaviors (e.g., hitting others) were prohibited if the question was phrased, "Are you allowed to. than if the question was phrased "is it against the rules to. We even found, thanks to a typographical error in the interview schedule, that responses to "Who decides what chores you do?" and "Who decides what chores to do?" differed. "

(Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.41)

The same research found that responses to oppositely worded questions (which should produce different responses as a person cannot logically agree with one while, at the same time, be in agreement with the other) is also problematic with Individuals experiencing .Learning Difficulties often providing contradictory answers. Sigelman et al (op cit) also state that questions including examples may also make a Learner more likely to use those examples in his/her answer even if they are not what s/he actually does or thinks:

"if a question calling for an enumeration of activities in a given category (e.g., sports) mentions examples (e.g., football and baseball), retarded persons will be more likely than usual to name the very activities used as examples."

(Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.40)

Indeed, there were so many issues emanating form the structure of questions that they went on to say:

"We can only recommend that there be extensive piloting of interview schedules to determine whether respondents understand and, if so, how they interpret alternatively phrased questions." (Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.41)

B. Using probing techniques to elicit further information is problematic:

"When interviewees are asked open-ended questions calling for an enumeration of activities, many cannot respond at all and those who can are likely to name very few activities. On the other hand, the strategy of probing indefinitely with "What else?" solves that problem but creates another that is more serious: over-reporting of activities in response to the implied demand to do so to the extent that answers lose validity. "

(Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.41)

"If one interviewer chooses to follow up an unclear answer with a simple yes-no questions while another chooses to use an either-or question to

pursue the matter, we can predict that the two interviewers are likely to get different answers. This is by no means a trivial issue, for our experience suggests that no matter how well original questions are designed, there is likely to be some need to follow-up or clarify vague or confusing answers." (Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.41)

C. Multiple choice questions with qualitative responses are typically unreliable:

"Multiple choice questions that call for responses along a quantitative dimension (e.g., a lot, some, not much, and not at all) appear to be generally useless as sources of information. They are relatively difficult for retarded persons to answer, in the first place; but more importantly, respondents appear to have difficulty attaching consistent meanings to such terms."

(Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.41)

"Unfortunately, we have no constructive advice for interviewers who seek quantitative information about such things as extent of involvement in various activities." (Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.44)

D. Closed Question format responses may be misleading:

Even before reading this research, I have been saying for many years that the use of the closed question format is problematic withing special education. This is covered further below in the section on closed questions. While such questions are quick and easy to use and seemingly to answer, Sigelman et al show throughout their 1983 study that this view is mistaken:

"Yes-no questions, despite the fact that they are easily answered by most retarded persons, are not useful in interviewing retarded persons. While this statement may seem strong, we have devoted more attention to yes-no questions than to any other format and we have found, with few exceptions, that retarded persons are highly likely to answer "yes" regardless of question content. "

(Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.44)

E. Open ended questions prove more difficult for people experiencing learning difficulties:

"Open-ended questions have one overriding limitation: they cannot be answered by very many retarded persons. As a result, they are not very useful at all in interviewing more severely retarded persons. " (Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.44)

However, they did find that open-ended questions which required a single response (for example: What drink did you have at break time?) were relatively well answered. Thus, question requiring a single word open-ended response is likely to be a more sound approach than the use of the closed question format.

So to overcome problems in checking for understanding what question forms are likely to be the more reliable?

- Multiple Choice Questions with quantifiable answers:

"Multiple choice questions offering discrete response alternatives, however, may have promise. In asking respondents what type of dwelling they lived in and how they got to school, we found that questions of this type worked well; better than open-ended questions on the same topics, for they enhanced responsiveness without sacrificing validity."

(Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.44)

Even though they suggest this as a better form of questioning, they do warn of the the dangers of response biases (see later this page). It should also be noted that Sigelman et al go on to report that the use of picture card based versions of the above may not be that advantageous :

"We are not confident that pictures provide enough of an advantage to warrant the effort involved in producing them."

However, when working with those who cannot respond to a question verbally, there is a definitely advantage in this approach and thuse it is one that I support in seeming contradiction to the above quote.

- either or questions using pictures or symbols:

"Of all the question formats we have tested, either-or questions, particularly those accompanied by pictorial representations of the alternatives, appear to be the best way of optimizing responsiveness and response validity."

(Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.45)

However, it should not be assumed that, even in using this methodology, it cannot be affected by a positional bias (see section below) and therefore this should always be kept in mind whilst undertaking the technique.

While Sigelman et al do not state this explicitly, it might be inferred that the use of real objects as choice items in an array (as opposed to pictures or symbols) would be the easiest method with which Learners could cope.

2. Closed Questions: Acquiescence and Other Issues

click to enlarge

click to enlarge

"However, the way in which a question is posed can influence the accuracy of the reports of child witnesses with disabilities (Bull, 1995; Bull & Cullen, 1992; Clare & Gudjonsson, 1993; Dent, 1986; Gordon, Jens, Hollings, & Watson, 1994; Gudjonsson & Gunn, 1982; Milne & Bull, 1999; Milne et al., 1999; Perlman et al., 1994). As suggested with children without disabilities, children’s responses tend to be most accurate when asked open-ended questions. The findings of a study conducted by Milne et al. concur with other research suggesting that specific, closed-ended questions, such as yes/no questions, resulted in the least reliable information."

(Nathanson & Crank 2004)

"The studies they reviewed showed that responsiveness increased with IQ, and that yes-no questions were easier to answer than either-or or multiple choice questions. They found that interview test-retest reliability was high when yes-no questions were asked. This was due to respondents being more likely on each occasion to acquiesce, that is say “yes”, rather than “no” regardless of the content of the question. Consistency of response to multiple choice questions was much lower. With either-or or questions such as “are you usually happy or sad”, there seemed to be a recency bias, with respondents choosing the second option regardless of which order the question was asked."

(Hensel 2000 page 18)

"There is a striking body of evidence attesting to the fact that interview data can be invalidated by a tendency on the part of respondents to give agreement responses independently of the content of the question.." (Sigelman et al 1983 page 2.31)

"The impact of acquiescence is so strong that we feel yes-no questions should be avoided entirely. " (Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.44)

"People with an intellectual disability at times have a desire to please others perceived to be in an authority role, including, possibly, the interviewer. Therefore, individuals may not answer questions truthfully, instead they may respond to questions in a certain way because they think that it is the “desired” response." (D'Eath et al 2005 page 2)

A closed question is one that can be answered using either a 'yes' or a 'no' ("Do you want tea?"). The opposite is an open question which cannot be answered in such a manner ("What do you want to drink?") and, thus, requires a more reliable response. It might be thought that in answering a closed question (with either a 'yes' or a 'no') offers a 50% chance of being correct but this would be wrong! As the majority of Individuals 'learn' to respond with a 'yes' (Sigelman et al 1981a) (are taught to answer yes is perhaps a more appropriate way of putting it) and the questions that are typically asked within educational settings require the 'yes' response then, in responding in the affirmative, the learner is likely to be correct above 80% of the time.

It has been known for over 40 years that Individuals Experiencing Learning Difficulties tend to use more positive words such as 'yes' and 'OK' (Beir, Starkweather, & Lambert 1969) although the aetiology of such behaviours was more likely to be seen as resulting from the individual and not as a didagenic factor (see Kohl 1973). It will be postulated (see Fly-swatting, this web page) that such a preponderance of positive forms may result as an unintentional (and unrecognised) outcome of interactions with Significant Others (including educational staff!).

"Overall, picture choice questions appear to hold promise greater than that of any other technique we have used as a method of gaining information from more severely retarded persons. " (Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.40)

(Nathanson & Crank 2004)

"The studies they reviewed showed that responsiveness increased with IQ, and that yes-no questions were easier to answer than either-or or multiple choice questions. They found that interview test-retest reliability was high when yes-no questions were asked. This was due to respondents being more likely on each occasion to acquiesce, that is say “yes”, rather than “no” regardless of the content of the question. Consistency of response to multiple choice questions was much lower. With either-or or questions such as “are you usually happy or sad”, there seemed to be a recency bias, with respondents choosing the second option regardless of which order the question was asked."

(Hensel 2000 page 18)

"There is a striking body of evidence attesting to the fact that interview data can be invalidated by a tendency on the part of respondents to give agreement responses independently of the content of the question.." (Sigelman et al 1983 page 2.31)

"The impact of acquiescence is so strong that we feel yes-no questions should be avoided entirely. " (Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.44)

"People with an intellectual disability at times have a desire to please others perceived to be in an authority role, including, possibly, the interviewer. Therefore, individuals may not answer questions truthfully, instead they may respond to questions in a certain way because they think that it is the “desired” response." (D'Eath et al 2005 page 2)

A closed question is one that can be answered using either a 'yes' or a 'no' ("Do you want tea?"). The opposite is an open question which cannot be answered in such a manner ("What do you want to drink?") and, thus, requires a more reliable response. It might be thought that in answering a closed question (with either a 'yes' or a 'no') offers a 50% chance of being correct but this would be wrong! As the majority of Individuals 'learn' to respond with a 'yes' (Sigelman et al 1981a) (are taught to answer yes is perhaps a more appropriate way of putting it) and the questions that are typically asked within educational settings require the 'yes' response then, in responding in the affirmative, the learner is likely to be correct above 80% of the time.

It has been known for over 40 years that Individuals Experiencing Learning Difficulties tend to use more positive words such as 'yes' and 'OK' (Beir, Starkweather, & Lambert 1969) although the aetiology of such behaviours was more likely to be seen as resulting from the individual and not as a didagenic factor (see Kohl 1973). It will be postulated (see Fly-swatting, this web page) that such a preponderance of positive forms may result as an unintentional (and unrecognised) outcome of interactions with Significant Others (including educational staff!).

"Overall, picture choice questions appear to hold promise greater than that of any other technique we have used as a method of gaining information from more severely retarded persons. " (Sigelman et al 1983 page 8.40)

3. Confabulation

Confabulation is a memory disorder that is defined as the spontaneous production of false memories -- either memories or events that never occurred, or of actual events that are displaced in time or space.

3. Fly-Swatting: The Occurrence of Learned Acquiescence in

Individuals Experiencing Significant Learning difficulties

click to enlarge

click to enlarge

4. Positional Preference, Positional Bias

click to enlarge

click to enlarge

"Response biases are patterns of behavior that do not conform to prevailing contingencies but instead are controlled by some idiosyncratic influence. These patterns presumably may be acquired and maintained in a number of ways. Some individuals may enter into a given procedure with a particular inherited disposition (e.g., being right handed and reaching out toward the right instead of across the body to the left when making selections). Others may have a history of reinforcement in which positional responding was reinforced explicitly (e.g., placing the fork on the left and the knife on the right) or adventitiously if responding in a particular position happens to contact reinforcement and thus becomes more likely in the future."

(Bourret 2012)

Positional Bias is a tendency for a Learner to make a selection from an array on the basis of its position rather than a conscious choice of the object itself. For example, a right handed person might always select the item on the right of any presented array. This behaviour may even be maintained if the array is presented in a different orientation: for example if the array were to be presented vertically rather than horizontally. The Learner will rotate his/her preference through 90 degrees to make the 'choice'.

Positional bias can also switch sides! For example, if the sun is shining through a window from the right in the morning, it might catch the rightmost item and illuminate it slightly more than the item on the left. However, as the sun moves during the day, in the afternoon it may illuminate the leftmost item slightly more. The Learner (especially one experiencing problems with visual acuity) may select on the basis of perceived illumination of the object.

The danger with positional bias is that staff may assume a selection has been made on the basis of comprehension of the choice itself. This may be especially the case if the selection of any item in the array is acceptable or if the known 'correct' response happens to coincide with the Learner's positional bias.

In the following YouTube video Bethany is working with Ashley. You will note that Bethany appears to have a positional right side preference. As such, is it it possible to claim any understanding of the letters themselves? No, Bethany always goes for the option on the right even when it's rotated through 90 degrees into a vertical orientation. Thus, when she appears to have made the correct choice, it is because the item happened to be presented in her preferred position. What can we state as a fact just from watching the video? Bethany is able to:

(Bourret 2012)

Positional Bias is a tendency for a Learner to make a selection from an array on the basis of its position rather than a conscious choice of the object itself. For example, a right handed person might always select the item on the right of any presented array. This behaviour may even be maintained if the array is presented in a different orientation: for example if the array were to be presented vertically rather than horizontally. The Learner will rotate his/her preference through 90 degrees to make the 'choice'.

Positional bias can also switch sides! For example, if the sun is shining through a window from the right in the morning, it might catch the rightmost item and illuminate it slightly more than the item on the left. However, as the sun moves during the day, in the afternoon it may illuminate the leftmost item slightly more. The Learner (especially one experiencing problems with visual acuity) may select on the basis of perceived illumination of the object.

The danger with positional bias is that staff may assume a selection has been made on the basis of comprehension of the choice itself. This may be especially the case if the selection of any item in the array is acceptable or if the known 'correct' response happens to coincide with the Learner's positional bias.

In the following YouTube video Bethany is working with Ashley. You will note that Bethany appears to have a positional right side preference. As such, is it it possible to claim any understanding of the letters themselves? No, Bethany always goes for the option on the right even when it's rotated through 90 degrees into a vertical orientation. Thus, when she appears to have made the correct choice, it is because the item happened to be presented in her preferred position. What can we state as a fact just from watching the video? Bethany is able to:

- repeat some sounds;

- reach out and take an item from a presented array;

Bourret (2012) showed that positional bias can be addressed through, at least, three methodologies:

"In summary, results of this study showed that position biases observed during preference assessments can be eliminated with contingencies that favor unbiased responding and that these changes are reflected under the prevailing (original) contingencies associated with assessment."

It should be noted that a positional preference or bias is not indicative of an ability to comprehend the situation. Although this might be the case it is only an assumption on our part. Where a Learner can make selections without positional bias, such selections are more indicative of understanding especially if the Learner continues to select correctly. However, while incorrect selections (without positional bias) are indicative of a lack of comprehension they cannot be held as fully indicative (the Learner may be having a joke, having an off day, refusing to cooperate for some reason, or some other explanation). Thus, while we can never prove a Learners lack of understanding (although we may infer it) ,we can positively show comprehension.

- Quality Training: In quality training a preferred item is paired with a non-preferred item (an item of lesser quality) such that the selection of the preferred item is the more likely.

- Magnitude Training: in magnitude training two preferred items are available in the choice but one of them is reinforced by presenting with a higher magnitude. Thus, there might be five of one item and only one of the other (five grapes as opposed to one piece of apple, for example).

- MagnitudeTraining plus error correction: As magnitude training plus blocking of an 'incorrect' choice and manual guidance to select the 'correct' option.

"In summary, results of this study showed that position biases observed during preference assessments can be eliminated with contingencies that favor unbiased responding and that these changes are reflected under the prevailing (original) contingencies associated with assessment."

It should be noted that a positional preference or bias is not indicative of an ability to comprehend the situation. Although this might be the case it is only an assumption on our part. Where a Learner can make selections without positional bias, such selections are more indicative of understanding especially if the Learner continues to select correctly. However, while incorrect selections (without positional bias) are indicative of a lack of comprehension they cannot be held as fully indicative (the Learner may be having a joke, having an off day, refusing to cooperate for some reason, or some other explanation). Thus, while we can never prove a Learners lack of understanding (although we may infer it) ,we can positively show comprehension.

5. Recency Bias

click to enlarge

click to enlarge

"Consistency of response to multiple choice questions was much lower. With either-or or questions such as “are you usually happy or sad”, there seemed to be a recency bias, with respondents choosing the second option regardless of which order the question was asked."

(Hensel 2000 page 18)

It has long been recognised that individuals with significant learning difficulties, when compared with others of the same age, have an impaired primacy but normal recency effect in memory (Bauer 1977; Newman & Hagen 1981, Sigelman et al. 1983). It is therefore, perhaps, unsurprising to find a 'recency bias' evident in their selection from verbally listed arrays. While this situation may be ameliorated somewhat through the use of symbol or photographic cue cards (March 1992), it does not follow that a Learner indication of a card from an array implies:

(Hensel 2000 page 18)

It has long been recognised that individuals with significant learning difficulties, when compared with others of the same age, have an impaired primacy but normal recency effect in memory (Bauer 1977; Newman & Hagen 1981, Sigelman et al. 1983). It is therefore, perhaps, unsurprising to find a 'recency bias' evident in their selection from verbally listed arrays. While this situation may be ameliorated somewhat through the use of symbol or photographic cue cards (March 1992), it does not follow that a Learner indication of a card from an array implies:

- knowledge or understanding of any of the items in the array;

- comprehension of the choice itself;

6. Referential Questioning

click to enlarge

click to enlarge

7. Sensory Tsunamis

8. Waiting Worries

click to enlarge

click to enlarge

Bibliography and References

Andre-Barron, D., Strydom, A., & Hassiotis, A. (2008). What to tell and how to tell: A qualitative study of information sharing in research for adults with intellectual disability. Journal of Medical Ethics, Volume 34, pp. 501 – 506.

Atkinson, D. (1988). Research interviews with people with mental handicaps, Mental Handicap Research, Volume 1 (1), pp. 75 – 90,

Balcazar, F.E., Keys, C.B., Kaplan, D.L., & Suarez-Balcazar, Y. (1998). Participatory

action research and people with disabilities: Principles and challenges. Canadian Journal of Rehabilitation, Volume 12, pp. 105 – 112.

Baroff, G.S. (1974). Mental retardation: Nature, cause, and management. Washington, DC: Hemisphere Publishing Corp.

Bauer, R.H. (1977). Memory processes in children with learning disabilities: Evidence for deficient rehearsal. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, Volume 24, pp. 415 - 430.

Bauer, R.H. (1979). Memory, acquisition, and category clustering in learning-disabled children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, Volume 27, pp. 365 - 383.

Beier, E.G., Starkweather, J.A., and Lambert, M.J. (1969). Vocabulary usage of mentally retarded children. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, Volume 73, pp. 928 - 934.

Bourret, J.C. (2012). Elimination Of Position-Biased Responding In Individuals With Autism And Intellectual Disabilities, Journal of Applied Behavioral Analysis. Volume 45(2): pp. 241 – 250.

Bowles, P.V., & Sharman, S.J. (2014). The Effect of Different Types of Leading Questions on Adult Eyewitnesses with Mild Intellectual Disabilities, Applied Cognitive Psychology, Volume 28 (1), pp. 129 – 134

Bravo, G., Paquet, M. & Dubois, M.F. (2003) 'Opinions regarding who should consent to research on behalf of an older adult suffering from dementia', Dementia, Volume 2, pp. 49 - 65.

Brown, M. (2007). Conducting focus groups with people with learning disabilities: Theoretical and practical issues. Journal of Research in Nursing, Volume 12, pp. 127–128.

Bull, R. (1995). Interviewing witnesses with communicative disability. In R. Bull & D. Carson (eds.), Handbook of psychology in legal contexts. Chichester: Wiley.

Bull, R. & Cullen, C. (1992). Witnesses who have mental handicaps. Edinburgh: Crown Office.

Cameron, L. & Murphy, J. (2006) 'Obtaining consent to participate in research: the issues involved in including people with a range of learning and communication disabilities', British Journal of Learning Disabilities, Volume 35, pp. 113 - 120.

Cardone, D. (1995). Interviewing people with a learning disability: A case study. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Birmingham University, Psychology Training Course.

Cardone, D. & Dent, H.R. (1996). Memory and interrogative suggestibility: The effects of modality of information presentation and retrieval conditions upon the suggestibility scores of people with learning disabilities, Legal and Criminological Psychology, Volume 1 (2), pp. 165 – 177

Cardone, D. (1999).. Exploring the Use of Question Methods: Pictures Do Not Always Help People with Learning Disabilities. The British Journal of Developmental Disabilities, Volume 45 (89), pp. 93 - 98.

Clare, I.C.H., & Gudjonsson, G.H. (1993). Interrogative suggestibility, confabulation, and acquiescence in people with mild learning disabilities (mental handicap): Implications for reliability during police interrogations, British Journal of Clinical Psychology, Volume 32 (3), pp. 295 – 301

Clare, I.C.H., & Gudjonsson, G.H. (1995). The Vulnerability Of Suspects With Intellectual Disabilities During Police Interviews: A Review And Experimental Study Of Decision-Making,

Mental Handicap Research, Volume 8 (2), pp. 110 – 128

Cooke, P. & Davies, G. (2001). Achieving best evidence from witnesses with learning disabilities: New guidance. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, Volume 29, pp. 84 - 87.

Coons, K.D., & Watson, S.L. (2013). Conducting Research with Individuals Who Have Intellectual Disabilities: Ethical and Practical Implications for Qualitative Research, Journal on Developmental Disabilities, Volume 19 (2), pp. 14 -24

D’Eath, M., McCormack, B., Blitz, N., Fay, B., Kelly, A., McCarthy, A., Magliocco, G., Morris, K., Swinburne, J., Tierney, E., & Walls, M. (2005). Guidelines for Researchers when Interviewing People with an Intellectual Disability, National Federation of Voluntary Bodies

Dagnan, D.J.,, Dennis, S., & Wood, H. (1994). A pilot study of the satisfaction of people with learning disabilities with the services they receive from Community Psychology services. The British Journal of Developmental Disabilities, Volume 40, pp. 38 - 44.

Dagnan, D.J., & Ruddick, L. (1995). The use of analogue scales and personal questionnaires for interviewing people with learning disabilities. Clinical Psychology Forum, Volume 69, pp. 21 - 24

Dattilo, J., Hoge, G., & Malley, S.M. (1996). Interviewing People with Mental Retardation: Validity and Reliability Strategies, Therapeutic Recreation Journal, Volume 30 (3), pp. 163 - 178

Dent, H.R. (1986). Experimental study of the effectiveness of different techniques of questioning mentally handicapped child witnesses. British Journal of Child Psychology, Volume 25, pp. 13 - 17.

Detheridge, T. (2000). Research Involving Children with Severe Learning Difficulties. In Researching Children’s Perspectives. Eds Lewis, A. & Lindsay, G. Open University Press Buckingham.

Dowse, L. (2009). “It’s like being in a zoo.” Researching with people with intellectual disability. Journal of Research in Special Education Needs, Volume 9, pp. 141 – 153.

Emerson, E., Hatton, C., Thompson, T., & Parmenter, T.R. (2008). Interviewing People with Intellectual Disabilities, The International Handbook Of Applied Research In Intellectual Disabilities, pp. 115 – 131

Felce, D. (2002). Gaining views from people with learning disabilities: Authenticity, validity and reliability, Presentation at ESRC seminar series: Methodological issues in interviewing children and young people with learning difficulties. School of Education, University of Birmingham. March

Finlay, W.M.L. & Lyons, E. (2001) Methodological issues in interviewing and using self-report questionnaires with people with mental retardation. Psychological Assessment, Volume 13, pp. 313 - 335

Finlay, W.M L. & Lyons, E. (2002) Acquiescence in Interviews With People Who Have Mental Retardation. Mental Retardation: Volume 40 (1), pp. 14 - 29.

Fisher, W., Piazza, C.C., Bowman, L.G., Hagopian, L.P., Owens, J.C., Slevin, I. (1992). A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. Volume 25 (2): pp. 491 – 498

Freedman, R.I. (2001). Ethical Challenges in the Conduct of research Involving persons with mental retardation, Mental Retardation, Volume 39 (2), pp. 130 - 141.

Galloway, C. (1967) Modification of a response bias through differential amount of reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. Volume 10 (4): pp. 375 – 382.

Gilbert, T. (2004). Involving people with learning disabilities in research: Issues and possibilities. Health and Social Care in the Community, Volume 12, pp. 298 – 308.

Godley, D. (1996). Tales of Hidden Lives: A Critical Examination of Life History Research with People who have Learning Difficulties. Disability and Society, Volume 11, pp. 333 - 348.

Gordon, B.N., Jens, K.G., Hollings, R., & Watson, T.E. (1994). Remembering activities performed versus those imagined: Implications for testimony of children with mental retardation. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, Volume 23, pp. 239 - 248.

Grove, N., Porter, J., Bunning, K., & Olsson, C. (1999) See What I Mean: Interpreting the Meaning of Communication by People with Severe and Profound Learning Difficulties: Theoretical and Methodological Issues. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, Volume 12 (3), pp. 190 - 203.

Gudjonsson, G.H. (1988). The relationship of intelligence and memory to interrogative suggestibility: The importance of range effects, British Journal Of Clinical Psychology, Volume 27 (2), pp. 185 – 187

Gudjonsson, G.H. (1990). The Relationship of Intellectual Skills to Suggestibility, Compliance and Acquiescence. Personality and Individual Differences, Volume 11, pp. 227 - 231

Gudjonsson, G.H. & Clare, I.C.H. (1995). The relationship between confabulation and intellectual ability, memory, interrogative suggestibility, and acquiescence. Personality Individual Differences, Volume 19, pp. 333 - 338

Gudjonsson G.H., & Henry, L. (2010). Child and adult witnesses with intellectual disability: The importance of suggestibility. Legal and Criminological Psychology, Volume 8 (2). pp. 241 -252

Gudjonsson G.H., & Young, S. (2011). Personality and deception. Are suggestibility, compliance and acquiescence related to socially desirable responding? Personality and Individual Differences, Volume 50 (2), pp. 192 – 195

Guess D., Benson H. & Sigel-Causey E. (1985). Concepts and Issues Related to Choice-Making and Autonomy among Persons with Severe Disabilities. Journal of the Association of Persons with Severe Handicaps, Volume 10, pp. 79 - 86.

Hartley, S.L., & MacLean W.E. Jr. (2006). A review of the reliability and validity of Likert-type scales for people with intellectual disability, Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, Volume 50 (11). pp. 813 – 827

Heal, L.W., & Sigelman, C.K. (1990). Methodological issues in measuring the quality of life of individuals with mental retardation. In R.L. Schalock & M.J. Begab (Eds.), Quality of Life:Perspectives and Issues (pp. 161-176). Washington, DC: American Association on Mental

Retardation.

Heal, L.W., & Sigelman, C.K. (1995). Response biases in interviews of individuals with limited mental ability, Journal Of Intellectual Disability Research, Volume 39 (4), pp. 331 – 340

Henry, L.A. & Gudjonsson, G.H. (1999). Eyewitness memory and suggestibility in children with mental retardation. American Journal on Mental Retardation, Volume 104 (6). pp. 491 - 508.

Henry L.A., & Gudjonsson, G.H. (2007), Individual and developmental differences in eyewitness recall and suggestibility in children with intellectual disabilities, Applied Cognitive Psychology, Volume 21 (3), pp. 361 – 381,

Howard, T.J., & Tyrer, S.P. (1998). Editorial: People with learning disabilities in the criminal justice system in England and Wales: a challenge to complacency, Criminal Behaviour And Mental Health, Volume 8 (3), pp. 171 – 177

Huang, S.F. & Oi, M. (2013). Responses to Wh-, Yes/No-, A-not-A, and choice questions in Taiwanese children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, Volume 27 (12) , pp. 969 - 985

Irvine, A. (2010). Conducting qualitative research with individuals with developmental disabilities: Methodological and ethical considerations. Developmental Disabilities Bulletin, Volume 38, pp. 21 – 34.

Kangas B.D, & Branch M.N. (2008), Empirical validation of a procedure to correct position and stimulus biases in matching-to-sample. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. Volume 90: pp. 103 – 112.

Kebbell, M.R. & Hatton, C. (1999). People with mental retardation as witnesses in court: A review. Mental Retardation, Volume 37, pp.179 - 187.

Kebbell, M.R., Hatton, C., Johnson, S.D. & O’Kelly, M.E. (2001). People with learning disabilities as witnesses in court: What questions should lawyers ask? British Journal of Learning Disabilities, Volume 29, pp. 98 - 102.

Kellett, M., & M. Nind, M. (2001). Ethics in quasi-experimental research on people with severe learning disabilities: dilemmas and compromises. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, Volume 29: pp. 51-55.

Kiernan, C. (1999). Participation in Research by People with Learning Disability: Origins and Issues, British Journal of Learning Disabilities, Volume 27 (2), pp. 43 – 47

Kitchin, R. (2000). The researched opinions on research: Disabled people and disability research. Disability & Society, Volume 15 (1), pp. 25 – 47.

Knox, M., Mok, M., & Parmenter, T.R. (2000). Working with the Experts: Collaborative Research with People with an Intellectual Disability. Disability and Society, Volume 15, pp. 49 - 61.

Kohl, H. (1973). Reading, how to. Harmondsworth, Penguin.

Kramer, J.M., Kramer, J.C., Garcia-Iriarte, E., & Hammel, J. (2011). Following through to the end: The use of inclusive strategies to analyse and interpret data in participatory action research with individuals with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, Volume 24, pp. 263 – 273.

Lamb, M.E., Hershkowitz, I., Orbach, Y., & Esplin, P.W. (2009). Interviewing Children with Intellectual and Communicative Difficulties, Chapter 9, Tell Me What Happened: Structured Investigative Interviews Of Child Victims And Witnesses, pp. 243 – 251

Lawrence, J. (2011), Agreement or acquiescence? Issues of informed consent within research working with vulnerable adults & the Mental Capacity Act (2005) (learning disabilities) , in: European Conference for Social Work Research, 23rd - 25th March 2011, Oxford, UK.

Lewis, A. (2002) Accessing Children’s views about inclusion and integration, Support for Learning, Volume 17 (3), pp. 110 - 116.

Lewis, A. (2004). ‘And When did You Last See Your Father?’ Exploring the Views of Children with Learning Difficulties/Disabilities, British Journal of Special Education, Volume 31 (1), pp. 3 – 9

Lewis, A., & Porter, J. (2004) Interviewing children and young people with learning disabilities:Guidelines for researchers and multi-professional practice, British Journal of Learning Disabilities, Volume 32 (4), pp. 191 – 197

Mactavish, J.B., Mahon, M.J., & Lutfiyya, Z.M. (2000). “I can speak for myself”: Involving individuals with intellectual disabilities as research participants. Mental Retardation, Volume 38, pp. 216 – 227.

Malik, P.B., Ashton-Shaeffer, C, & Kleiber, D.A. (1991). Interviewing young adults with mental retardation: A seldom used research method. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, Volume 25, pp. 60 - 73.

March, P. (1992). Do photographs help adults with severe mental handicaps make choices?, The British Journal of Mental Subnormality, Volume 38 (2), pp. 122 - 128

Matysiak, B. (2001). Interpretive research and people with intellectual disabilities: Politics and practicalities. Research in Social Science and Disability, Volume 2, pp. 185 – 207.

Miles, K.L.. Powell, M.B., Gignac, G.G., & Thomson, D.M. (2007), How well does the Gudjonsson Suggestibility Scale for Children, version 2 predict the recall of false details among children with and without intellectual disabilities? Legal And Criminological Psychology, Volume 12 (2), pp. 217 – 232

Milne, R. & Bull, R. (1996). Interviewing children with mild learning disability with the cognitive interview. Issues in Criminological and Legal Psychology, Volume 26, pp. 44 - 51.

Milne, R. & Bull, R. (2001). Interviewing witnesses with learning disability for legal purposes. British Journal of Learning disabilities, Volume 29, pp. 93 - 97.

Milne, R., Clare, I.C.H., & Bull, R. (1999). Interviewing adults with learning disability with cognitive interview. Psychology, Crime Law, Volume 5, pp. 81 - 100.

Nathanson, R. & Crank, J.N. (2001). Increasing accurate responses in children with disabilities during forensic questioning. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco, CA.

Nathanson, R. & Crank, J.N. (2002). Facilitating comprehension monitoring in children with learning disabilities. Paper presented at the 2002 Council for Exceptional Children Annual Convention, Charlotte, NC.

Nathanson, R., Crank, J.N., & Saywitz, K. (2002). Enhancing narrative discourse in children with learning disabilities. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Nathanson, R. & Crank, J.N. (2004). Interviewing Children with Disabilities, In - NACC Children’s Law Manual – 2004 Edition, Chapter 4

Nathanson, R. & Platt, M. (2004). Attorneys’ perceptions of child witnesses with mental retardation. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Nathanson, R. & Saywitz, K. (2002). The effects of the courtroom context on children’s memory and anxiety. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Newman, R.S., & Hagen, J.W. (1981). Memory Strategies in Children with Learning Disabilities, Journal Of Applied Developmental Psychology, Volume 1, pp. 297 - 312

Nind, M. (2008). Conducting qualitative research with people with learning, communication and other disabilities: Methodological challenges. National Centre for Research Methods

Oi, M. (2010). Do Japanese children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder respond differently to Wh-questions and Yes/No-questions? Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, Volume 24 (9), pp. 691 - 705

Paterson, B., & Scott-Findlay, S. (2002). Critical issues in interviewing people with traumatic brain injury. Qualitative Health Research, Volume 12, pp. 399 – 409.

Perlman, N.B., Ericson, K.I., Esses, V.M., & Isaacs, B.J. (1994). The developmentally handicapped witness: Competency as a function of question format. Law and Human Behavior, Volume 18, pp. 171 - 187.

Prosser, H., & Bromley, J. (2012). Interviewing People with Intellectual Disabilities, In - Eric Emerson, Chris Hatton, Kate Dickson, Rupa Gone, Amanda Caine, & Jo Bromley (Eds). Clinical Psychology and People with Intellectual Disabilities, Second Edition, pp. 105 - 120, Wiley and Sons Ltd

Ramirez, S.Z. ( 2005), Evaluating Acquiescence to Yes–No Questions in Fear Assessment of Children With and Without Mental Retardation, Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities Volume 17 (4), pp. 337 - 343

Rapley, M. & Antaki, C. (1996). A Conversation Analysis of the ‘Acquiescence’ of People with Learning Disabilities, Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, Volume 6 (3), pp. 207 – 227

Rodgers, J. (1999). Trying to get it Right: Undertaking Research Involving People with Difficulties. Disability & Society, Volume 14 (4), pp. 421 - 433.

Rosen, M., Floor, L., & Zisfein, L. (1974). Investigating the phenomena of acquiescence in the mentally handicapped: 1. Theoretical model, test development, and normative data, British Journal of Mental Subnormality, Volume 20, pp. 56 - 68

Scott, J., Wishart, J., & Bowyer, D. (2006) 'Do consent and confidentiality requirements impede or enhance research with children with learning disabilities', Disability and Society, Volume 21 (3), pp. 273 - 287

Sigelman, C.K., Schoenrock, C.J., Spanhel, C.L., Hromas, S.G., Winer, J.L., Budd, E.C., & Martin, P.W. (1980). Surveying Mentally Retarded Persons: Responsiveness and Response Validity in Three Samples. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, Volume 84 (5), pp. 479 - 486.

Sigelman, C.K., Budd, E.C., Spanhel, C.L. & Schoenrock, C.J. (1981a) When in doubt say yes: acquiescence in interviews with mentally retarded persons. Mental Retardation. Volume 19, pp. 53 - 58.

Sigelman, C.K., Budd, E.C., Spanhel, C.L. & Schoenrock, C.J. (1981b). Asking questions of mentally retarded persons: a comparison of yes-no and either-or formats, Applied Research in Mental Retardation, Volume 2, pp. 347 - 357

Sigelman, C.K., Schoenrock, C.J.,Winer, J.L., Spanhel, C.L., Hromas, S.G., Martin, P.W., Budd, E.C., & Bensberg, G.J. (1981). Issues in interviewing mentally retarded persons: An empirical study. In R.H. Bruininks, C.E. Meyers, B.B. Sigford, & K.C. Lakin (Eds.), Deinstitutionalization and community adjustment of mentally retarded people (Monograph No. 4). Washington, D.C.: American Association on Mental Deficiency.

Sigelman, C.K., Budd, E.C., Winer, J.L., Schoenrock, C.J., & Martin, P.W. (1982). Evaluating Alternative Techniques of Questioning Mentally Retarded Persons. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, Volume 86 (5), 1982, pp. 511-518.

Sigelman, C.K., Winer, J.L. & Schoenrock, C.J. (1982). The responsiveness of mentally retarded persons to questions. Education and Training of the Mentally Retarded, Volume 17, pp. 120 - 124.

Sigelman, C.K., Schoenrock, C.J., Budd, E.C., Winer, J.L., Spanhel, C.L., Martin, P.W., Hromas, S.G., & Bensberg, G.J. (1983). Communicating with Mentally Retarded Persons: Asking Questions and Getting Answers, Research and Training Center in Mental Retardation, Texas Tech University

Sigelman, C.K., & Budd, E.C. (1986). Pictures as an aid in questioning mentally retarded persons, Rehabilitation Counselling Bulletin, Volume 29, pp. 173 - 181

Stalker, K. (1998). Some Ethical and Methodological Issues in Research with People with Learning Difficulties. Disability and Society, Volume 13 (1), pp. 5 - 19.

Sudman, S., & Bradburn, N.M. (1974) Response effects in surveys: A review and synthesis. Chicago: Aldine.

Swanson, H.L. (1979). Developmental recall lag in learning-disabled children: Perceptual deficit or verbal mediation deficiency? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, Volume 7 (2), pp. 199.-.210

Tarver, S.G., Hallahan, D.P., Cohen, S.B., & Kauffman, J.M. (1977). The development of visual selective attention and verbal rehearsal in learning disabled boys. Journal of Learning Disabilities, Volume 10 (8), pp. 491 - 500.

Tarver, S.G., Hallahan, D.P., Kauffman, J.M., & Ball, D.W. (1976). Verbal rehearsal and selective attention in children with learning disabilities: A developmental lag. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, Volume 22 (3), pp. 375 - 385.

Vorndran, C.M. (2005). The effects of discrimination training on choice-making accuracy during symbolic preference assessment formats, Doctoral Dissertation submitted to Louisiana State University

Wadsworth, J.S., & Harper, D.C. (1991). Increasing the reliability of self-report by adults with moderate mental retardation. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, Volume 16 (4), pp.228 - 232.

Walmsley, J. (2001). Normalisation, Emancipatory Research and Inclusive Research in Learning Disability, Disability & Society, Volume 16 (2),

pp. 187 - 205.

Ward, L. (1996). Seen and Heard: Involving disabled children and young people in research and development projects. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Ward, L. (1998). Practising partnership: Involving people with learning difficulties in research. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, Volume 26, pp. 128 - 132.

Ward, K. and Trigler J.S. (2001) Reflections on Participatory Action Research with People who have Developmental Disabilities, Mental Retardation, Volume 39 (1), pp. 57 - 59.

Have Your Say

If you wish to make a comment about any issue raised on this page or ask for further information, please use the form below

Return To Top of the Page

Click on the arrow button left to return to the top of this page