Metamorphosis

Tony Jones M.ED., B.Ed.(Hons), Cert.Ed.Res., Cert.Ed.Man., Cert.Ed.

Comment & Contact Tony on form at end of this page / article

This is a complete version of an article published in the Communication Matters Journal.

Tony Jones M.ED., B.Ed.(Hons), Cert.Ed.Res., Cert.Ed.Man., Cert.Ed.

Comment & Contact Tony on form at end of this page / article

This is a complete version of an article published in the Communication Matters Journal.

I am a disabled man in my late sixties. Over a year ago, in August 2020, I had a major stroke that put me in hospital for several weeks. The stroke left me with a left hemiplegia, paralysed completely down the left-hand side of my body and extremely weak core muscle strength. It also meant that I became doubly incontinent and was fitted with a catheter. Full-time catheterisation meant that I was prone to bladder infections (which are not pleasant). It seemed that I was on a permanent prescription for bladder and urinary tract infections and the antibiotics added to the volume of pills and potions that I have to swallow every day. The problem is that, following the stroke, I found swallowing difficult and would often choke when eating or drinking.

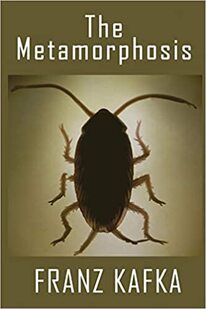

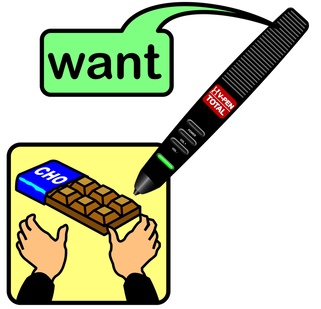

Thus, I had to have all my drinks thickened and avoid certain foods. The stroke also really affected my speech and talking became something of an effort with very limited results. Indeed, if I am emotional, or in pain, or my throat is dry, or I am not feeling well, or for reasons unknown, I cannot speak at all and have to resort to using my single handed version of Makaton (because my left hand is not functioning) sign language that I call Maka-One or, alternatively, my V-Pen and board. As if not all that was enough, I found myself having to cope with lengthy periods of pain and poor post-hospital provision. All of this was during the Covid lock-down, which further compounded my nightmare. Having a stroke made me feel like Gregor Samsa, the salesperson in Franz Kafka’s surreal book (‘The Metamorphosis’: Die Verwandlung. Original in German, 1915), awakening one morning, only to discover that he had inextricably transformed overnight into a very different, somewhat repulsive, being. I awoke, knowing I would have to learn to deal with a new reality; one in which many people might view and treat me differently.

Thus, I had to have all my drinks thickened and avoid certain foods. The stroke also really affected my speech and talking became something of an effort with very limited results. Indeed, if I am emotional, or in pain, or my throat is dry, or I am not feeling well, or for reasons unknown, I cannot speak at all and have to resort to using my single handed version of Makaton (because my left hand is not functioning) sign language that I call Maka-One or, alternatively, my V-Pen and board. As if not all that was enough, I found myself having to cope with lengthy periods of pain and poor post-hospital provision. All of this was during the Covid lock-down, which further compounded my nightmare. Having a stroke made me feel like Gregor Samsa, the salesperson in Franz Kafka’s surreal book (‘The Metamorphosis’: Die Verwandlung. Original in German, 1915), awakening one morning, only to discover that he had inextricably transformed overnight into a very different, somewhat repulsive, being. I awoke, knowing I would have to learn to deal with a new reality; one in which many people might view and treat me differently.

All my working life, I was involved, in one way or another, with People Of Disability (POD) and or learning difficulties. I also was involved in the provision of training for professionals and support workers. I worked alongside gifted Speech and Language Therapists, Occupational Therapists, and Physiotherapists as well as many talented teachers and support staff in many different countries. The focus of the training I provided concerned good practice in education and, support provision for staff working with individuals experiencing special needs. It now seems somewhat ironic that I am in need of that support myself! The irony is not lost on me. I had become an I.R.O.N. (Individual totally Reliant on Others for Needs) P.O.D. (Person Of Disability). In POD, the Person comes before the disability but the use of 'of' suggests that the disability defines the Person. Still, the Person comes first, the disability second. I am a POD. What type of POD am I? I am an IRON POD. In IRON the Individual comes first. The Reliance upon Others follows. Needs comes last but defines the Individual, an Individual with needs. The needs are supplied by Others. Thus, putting it all together, it assembles as IRON POD.

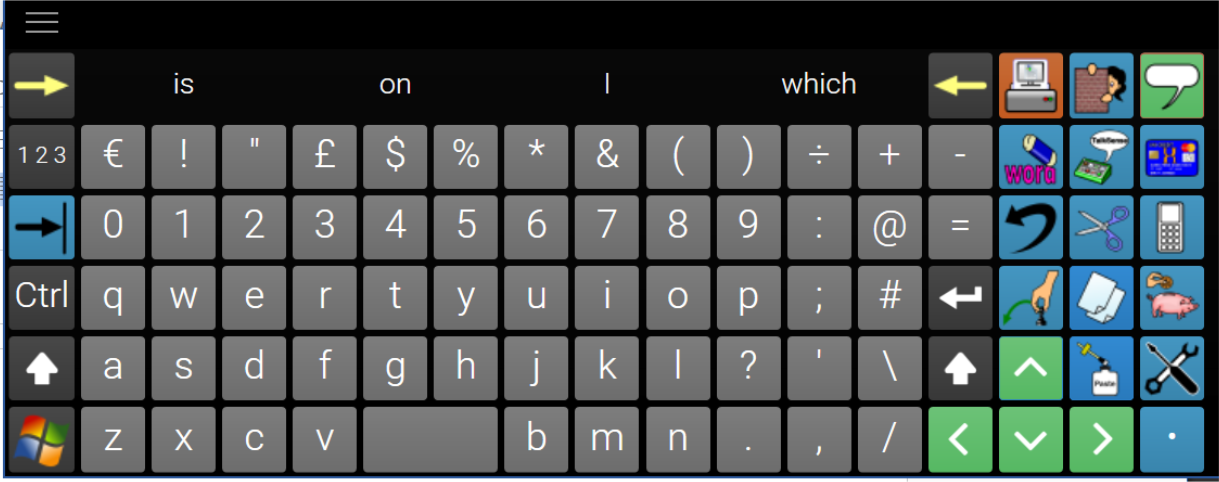

I write this article whilst in bed using a wireless trackball controlling my computer connected to a large television screen at the foot of the bed. I am using an on-screen keyboard to type. I have tried many on-screen keyboards but each did not meet my needs. The runner-up was Click2Speak which is very good and is free but, by far the best, is The Grid. I used The Grid to create my own on-screen keyboard (shown below). It can do just about everything that I need it to do. It can even speak any text that I highlight. I sometimes use it to communicate but my on-screen keyboard was not designed for that particular purpose.

I write this article whilst in bed using a wireless trackball controlling my computer connected to a large television screen at the foot of the bed. I am using an on-screen keyboard to type. I have tried many on-screen keyboards but each did not meet my needs. The runner-up was Click2Speak which is very good and is free but, by far the best, is The Grid. I used The Grid to create my own on-screen keyboard (shown below). It can do just about everything that I need it to do. It can even speak any text that I highlight. I sometimes use it to communicate but my on-screen keyboard was not designed for that particular purpose.

Communication is important:-

Speech is power in our society. Hence, it should surprise no one that freedom of speech is the first right guaranteed to all Americans in the Bill of Rights. Deprived of speech or another means of effective communication, individuals become invisible. They are simply not heard. They are silenced. And, when people are silenced, others quickly lose sight of their right to be a part of humanity! (Bryen D. 1993)

The limits of my language mean the limits of my world (Wittgenstein L. 1953)

No one in this day and age can possibly underestimate the importance of language. We are surrounded by talking (Jeffree D. & McConkey R. 1976)

Speech is the most important thing we have. It makes us a person and not a thing. No one should ever have to be a 'thing.' (Joseph D. 1986)

The ability to communicate, that is, to interact socially and to make needs and wants known, is central to the determination of an individual’s quality of life. The power of communication is especially important for the severely handicapped .... these individuals face a lifetime of substantial, if not total dependence on others; hence, their ability to communicate and establish some control over their environment must be recognized as a priority in their programming (Light J., McNaughton D., & Parnes P. 1986)

And to be defective in language, for a human being, is one of the most desperate of calamities, for it is only through language that we enter fully into our human estate and culture, communicate freely with our fellows, acquire and share information. If we cannot do this, we will be bizarrely disabled and cut off - whatever our desires, or endeavours, or native capacities. And indeed, we may be so little able to realize our intellectual capacities as to appear mentally defective. (Sacks O. 1989)

My basic problem was one I’ve encountered through my whole life. When you can’t talk, and people believe that your mind is as handicapped as your body, it’s awfully difficult to change their opinion. (Sienkiewicz‑Mercer R. & Kaplan S. B. 1989)

A communication handicap is quite different from other handicaps. It affects the manner in which you relate to other people and how they relate to you, it pervades everything you do (Oakley M. 1991)

Imagine a life without words! Trappist monks opt for it. But most of us would not give up words for anything. Every day we utter thousands and thousands of words. Communicating our joys, fears, opinions, fantasies, wishes, requests, demands, feelings - and the occasional threat or insult - is a very important aspect of being human. The air is always thick with our verbal emissions. There are so many things we want to tell the world. Some of them are important, some of them are not. But we talk anyway - even when we know that what we are saying is totally unimportant. We love chitchat and find silent encounters awkward, or even oppressive. A life without words would be a horrendous privation. (Katamba F. 1994)

Language is so tightly woven into human experience that it is scarcely possible to imagine life without it. Chances are that if you find two or more people together anywhere on earth, they will soon be exchanging words. When there is no on to talk with, people talk to themselves, to their dogs, even to their plants. In our social relations, the race is not to the swift but to the verbal - the spellbinding orator, the silver-tongued seducer, the persuasive child who wins the battle of wits against a brawnier parent. Aphasia, the loss of language following brain injury, is devastating, and in severe cases family members may feel that the whole person is lost forever. (Pinker S. 1994)

People with communications deficits face particular challenges unique to them. It is through communicative interactions that individuals are able to transcend the barriers erected by disability. Being unable to speak creates special problems. A well-used communication aid can be an effective tool for integrating people with communication disabilities into the culture of a particular workplace. (Dickerson L. 1995)

And language remains our greatest treasure, for without it we are confined to a world that, while not one of social isolation, is surely one that is a great deal less rich. Language makes us members of a community, providing us with the opportunity to share knowledge and experiences in a way no other species can. (Dunbar R. 1996)

Communication is the basis of learning. Communication is essential for the acquisition of knowledge. How are we to tell whether an individual (with severe physical impairment) has internalised language unless s/he can communicate? It is imperative that the neurological development of language skills are given every opportunity to proceed without impediment (Jones A.P. 1996)

Speech is power in our society. Hence, it should surprise no one that freedom of speech is the first right guaranteed to all Americans in the Bill of Rights. Deprived of speech or another means of effective communication, individuals become invisible. They are simply not heard. They are silenced. And, when people are silenced, others quickly lose sight of their right to be a part of humanity! (Bryen D. 1993)

The limits of my language mean the limits of my world (Wittgenstein L. 1953)

No one in this day and age can possibly underestimate the importance of language. We are surrounded by talking (Jeffree D. & McConkey R. 1976)

Speech is the most important thing we have. It makes us a person and not a thing. No one should ever have to be a 'thing.' (Joseph D. 1986)

The ability to communicate, that is, to interact socially and to make needs and wants known, is central to the determination of an individual’s quality of life. The power of communication is especially important for the severely handicapped .... these individuals face a lifetime of substantial, if not total dependence on others; hence, their ability to communicate and establish some control over their environment must be recognized as a priority in their programming (Light J., McNaughton D., & Parnes P. 1986)

And to be defective in language, for a human being, is one of the most desperate of calamities, for it is only through language that we enter fully into our human estate and culture, communicate freely with our fellows, acquire and share information. If we cannot do this, we will be bizarrely disabled and cut off - whatever our desires, or endeavours, or native capacities. And indeed, we may be so little able to realize our intellectual capacities as to appear mentally defective. (Sacks O. 1989)

My basic problem was one I’ve encountered through my whole life. When you can’t talk, and people believe that your mind is as handicapped as your body, it’s awfully difficult to change their opinion. (Sienkiewicz‑Mercer R. & Kaplan S. B. 1989)

A communication handicap is quite different from other handicaps. It affects the manner in which you relate to other people and how they relate to you, it pervades everything you do (Oakley M. 1991)

Imagine a life without words! Trappist monks opt for it. But most of us would not give up words for anything. Every day we utter thousands and thousands of words. Communicating our joys, fears, opinions, fantasies, wishes, requests, demands, feelings - and the occasional threat or insult - is a very important aspect of being human. The air is always thick with our verbal emissions. There are so many things we want to tell the world. Some of them are important, some of them are not. But we talk anyway - even when we know that what we are saying is totally unimportant. We love chitchat and find silent encounters awkward, or even oppressive. A life without words would be a horrendous privation. (Katamba F. 1994)

Language is so tightly woven into human experience that it is scarcely possible to imagine life without it. Chances are that if you find two or more people together anywhere on earth, they will soon be exchanging words. When there is no on to talk with, people talk to themselves, to their dogs, even to their plants. In our social relations, the race is not to the swift but to the verbal - the spellbinding orator, the silver-tongued seducer, the persuasive child who wins the battle of wits against a brawnier parent. Aphasia, the loss of language following brain injury, is devastating, and in severe cases family members may feel that the whole person is lost forever. (Pinker S. 1994)

People with communications deficits face particular challenges unique to them. It is through communicative interactions that individuals are able to transcend the barriers erected by disability. Being unable to speak creates special problems. A well-used communication aid can be an effective tool for integrating people with communication disabilities into the culture of a particular workplace. (Dickerson L. 1995)

And language remains our greatest treasure, for without it we are confined to a world that, while not one of social isolation, is surely one that is a great deal less rich. Language makes us members of a community, providing us with the opportunity to share knowledge and experiences in a way no other species can. (Dunbar R. 1996)

Communication is the basis of learning. Communication is essential for the acquisition of knowledge. How are we to tell whether an individual (with severe physical impairment) has internalised language unless s/he can communicate? It is imperative that the neurological development of language skills are given every opportunity to proceed without impediment (Jones A.P. 1996)

A stroke can take away the power of speech. My stroke left me with very poor speech. On good days, I can just about make myself understood but, on bad days, I have no speech at all. I have worked with AAC (Alternative and Augmentative Communication) throughout my working life. I have taught AAC, designed and developed AAC, marketed AAC, and lectured on AAC all over the world. After the stroke, I became a consumer of AAC. I am probably the only person in the world to have occupied each of those roles. The irony of becoming a user of AAC is not lost on me. While in hospital, I used a combination of very poor natural speech, my V-Pen and board, Makaton signing and, writing in a notebook at various times in order to communicate and get what I needed to say across to others. Makaton signing is tailored for use with two able hands, I only had one functioning upper limb following the stroke and even that was not very able. I had to use Makaton creatively, adapting signs made using two hands into a single handed form. It would not have mattered if I had the use of my left hand however, because none of my nurses knew any Makaton. I had to teach them some signs by signing a single word and then writing down its meaning in my notebook. A very slow way to communicate! I also used my V-Pen and board. The V-Pen is a clever pen-shaped device that can recognise symbols and speak their meaning when a symbol is touched. I was involved in the system's development when I worked for Unlimiter in Taipei, Taiwan. The nurses were more interested in the Pen, it's technology, and how it worked than what I was trying to say. Many times I forgot my intended message because I became distracted in performing to an audience of nurses showing them the Pen! I had built several communication boards for use with the Pen whilst in Taiwan which I had at home. These were brought for me to use but, while the V-Pen was a perfect AAC system for use in hospital, unfortunately the boards that I had designed were not! They did not have the vocabulary necessary for use on a hospital ward. I busied myself with the design of a board that would be highly suited for this purpose and could be available on every hospital ward throughout the world. The V-Pen system is perfect for that situation because it is small, portable, and requires virtually no learning; a person could learn to use it in seconds. The spelling board option can say virtually anything provided the Patient can spell. Put that together with a couple of symbol boards and you have a really good communication system for nurses to loan to Patients during their hospital stay. I should state, for the record, that I do not benefit financially from this system and have not worked for the company for ten years.

Yes, communication matters. My lack of effective communication let me down on several occasions both during my time in hospital and during the year afterwards spent at home. A few of those experiences are detailed in this article. I continue to have communication difficulties nearly a year post-stroke. I guess I will have them for the remainder of my life. Silence is not golden (despite what the song says). I am already beginning to notice subtle differences in the way I am treated by others. Others are not comfortable with silence and, as I take longer to respond to communication from other people, will 'jump in' and continue communicating in what, I presume, is an effort to ease the discomfort that I must be feeling not being able to communicate effectively.There have been other, some very noticeable, changes too:

Me (struggling to speak) "Don't call it a bib. I am an adult."

2nd Carer to 1st Carer: "What did he say?"

1st Carer to 2nd Carer: " I haven’t a clue"

(and then the Carers start the normal lunch visit procedure with no attempt to ask and clarify my statement.)

Adding ‘or something else’ makes possible a choice that puts the client in control. Of course, multiple options within a single question posed to a person without any means to communicate is, in itself, problematic. It is easily solved by presenting the options, one at a time, allowing the person to respond ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to each. If the person responds affirmatively to ‘something else’, you have the further issue of discovering which of all available drinks the person wants. However, that task is not so arduous as it might appear. The person is in a room within a building and there will be a finite number of drinks available. Once you get to know a person, you will also get to know the person’s preferences. Presenting personal preferences prioritising previously picked options will likely quickly reach a choice. Provision of real choice puts the individual in control and gives the person a voice.

• People think that they have the right to make decisions on my part for choices in my life. Again, taking over control and taking it away from me. You do not have the right to take control of another person just because they have an issue with communication or a learning difficulty. Ways must be found to involve the individual in her / his life choices, no matter how difficult that may be. My Carers were cleaning my bottom. I was screaming in pain. Eventually, I said, “stop please stop.” Over and over again. Did they stop? No, they continued cleaning my bottom despite my obvious distress. They took the decision to continue saying things to justify their actions, “we have got to get you clean otherwise you will be in more pain” and, “sorry just a little longer”, “nearly finished”, “almost there”, while I was begging them to stop. My decision was ignored, they took the decision for me.

Yes, communication matters. My lack of effective communication let me down on several occasions both during my time in hospital and during the year afterwards spent at home. A few of those experiences are detailed in this article. I continue to have communication difficulties nearly a year post-stroke. I guess I will have them for the remainder of my life. Silence is not golden (despite what the song says). I am already beginning to notice subtle differences in the way I am treated by others. Others are not comfortable with silence and, as I take longer to respond to communication from other people, will 'jump in' and continue communicating in what, I presume, is an effort to ease the discomfort that I must be feeling not being able to communicate effectively.There have been other, some very noticeable, changes too:

- People will invade my personal space and position their face a few inches from mine to talk to me.

- The prosody of the speech of others has changed.

- I am communicatively patronised by some.

- The speech of others has slowed.

- Sentences are shorter.

- The use of closed questions has increased.

- I have experienced the absence phenomenon in which people will talk together across me (even about me) as though I wasn’t there.

- Assumption, by others, that my physical disability equates with a cognitive impairment is reflected in the communication used by others, particularly those who do not know me. My Carers often leave me in a worse state than before they arrived. My bottom is sore and very sensitive. Yet, despite my screams of pain as the Carers clean my bottom, they just say "sorry" and carry on regardless of my feelings doing the same thing in the same way. Even when told to “stop”, I get platitudes like, "nearly finished ", "just a little bit more to do", "I have got to get you clean" and then continuing in wiping me in the same way. As far as I am concerned, when I scream in pain it is a clear indication that I need them to alter the methodology in use and adopt a gentler practice. When I say "Stop! ", I expect them to STOP what they are doing and try a different approach (with my approval). I am not intellectually impaired and I am not a child in need of direction, I am an intelligent adult and expect to be treated as such. I don't expect to feel worse after the Carers have finished than before they started.I do expect my communication, limited though it is, to be respected and for it not to be ignored.

- The ‘Does he take sugar?’ practice has occurred many times. It is truly demeaning to ignore an individual (experiencing communication difficulties) completely and address questions to others. It is a common issue (Wagner 1991; Hogg & Wilson 2004). Radio 4 used to broadcast a weekly series entitled ‘Does He Take Sugar?’ (It started in 1977 and ran for about twenty years) in which it covered the treatment of the disabled. The title of the program refers to an all-to-frequent occurrence, in which a person asks another (other than the person with the disability) a question about a topic avoiding talking to the person with the disability. People often discuss items concerning someone with a disability, while s/he is present, and do not include the person even though s/he can speak for him / herself. The radio series made this type of thing explicit and gave People Of Disability (POD) a voice.

- Asking me a question and then answering it for me.

- Asking a question and then immediately asking more questions without allowing me the time to respond to any of them. One morning the Carers asked me a quotation. By the time I had the chance to answer in sign, they had already asked several more questions. I signed "I don't know". The Carers hadn't got a clue what I was saying. They would have not known, to which of the questions they had asked, my signing was the response, because they had moved on so far beyond the original question. “Where’s it hurting?” - “Is it your leg?” - “Do you want me to get the doctor?” - “Do you want us to move you?” - “Are you feeling sick?” - “Do you feel hot?” - “What can we do to help?”

“STOP asking so many questions all at once!” - Increase in the use of ‘ terms of endearment. My Carers would often use ‘love’, ‘darling’, ‘me duck’ or some other term of endearment when addressing me until I told them to stop.

- Acting on erroneous assumptions of understanding of my communication without permission to act.

- Taking control. With no communication there is no control and ‘Control is the Goal’. While in hospital, I was in a bed with a faulty bed control. It was night and the lights were out. I was very uncomfortable but could do nothing to help myself except to try to use the bed control to reposition my body a little. In the poor light, I hit the ‘raise bed’ function thinking that I was raising the top of the bed just to sit up. When I realised that I had raised the whole bed by mistake, I tried to lower it but that particular function was faulty and not working on my control, so the bed remained raised in its highest position. A while later, a night duty nurse, on seeing my elevated position, came up to me and started to scold me like a little child. I tried to explain but my speech was bad following the stroke and I struggled to speak. The nurse made no effort to listen and comprehend my poor communication and continued to berate me. He used the separate bed control at the foot of the bed to lower the bed. He told me that I should go to sleep and stop messing with the bed control as it was not safe to be “way up in the air.” He then positioned my hand control out of my reach and left me completely helpless.

- Providing two or more alternatives to an initially closed question. “Do you want a drink?” ••• “would you like tea?” “Perhaps a cup of coffee?” Not comprehending that I should be given time to respond to the initial question and following with multiple closed questions did not allow me to simply sign “yes” or “no”. A further mix up was caused when my Carers asked if I wanted cream on my bottom and I told them that I wanted my bottom leaving alone. A while later, I had been rolled onto my left side and they asked if I was sure that I didn’t want them to do anything with my bottom because it needed wiping. I nodded as best as I could while on my side. The Carers took my nod to mean that I was now OK with them wiping my bottom when I was responding to their question, “was I sure ••• ?”. They then wiped my bottom and I was not pleased!

- The use of age inappropriate language. For example, “Good boy” is not appropriate for an adult male many years your senior. When I am eating , I usually have a tea towel across my chest such that, if I accidentally drop any hot food, it falls onto the towel and not my bare flesh. Once, the Carers arrived before I started my lunch but after the towel was in place:

1st Carer: "Oh! You've got your bib on ready for dinner."

Me (struggling to speak) "Don't call it a bib. I am an adult."

2nd Carer to 1st Carer: "What did he say?"

1st Carer to 2nd Carer: " I haven’t a clue"

(and then the Carers start the normal lunch visit procedure with no attempt to ask and clarify my statement.)

- Reluctance to relinquish control. Carers like to be in control. Early in my first period in hospital following the stroke, I had to call a nurse to look at my catheter bag, which was full. The nurse said,

“Oh Christ!”

and hurried to get a disposable bottle in which to empty it. I then asked the nurse for the bed control. She gave me a quizzical look and asked,

“What do you want that for?”

I explained that I wanted to raise the top of the bed. She asked,

“Do you want to sit up?”

and using the bed control herself proceeded to raise the top of the bed saying,

“Tell me when.”

I protested,

“No, give the control to me.”

My speech was very poor, affected by the stroke, and the nurse just carried on, in control, saying,

“Too high?”

and began lowering the top of the bed! I repeated, as clearly as I was able,

“No, give it to me.”

This time the nurse appeared to understand me and passed me the control stating,

“Fine, do it yourself.”

She was not pleased as she walked away. Carers like to be in control. It is not the Carer that needs to be in control, it is the Client. The goal is control. Give the Client, the Patient, the Learner the means to take control. Control of the Carers, the Clinicians, the environment, over the gadgets in the environment, over my own being, over Everything. Control is empowering. Take away control and you take away dignity. Loss of control is demeaning and handicapping in the true sense of the word. Another time, while in hospital, I found myself with no access to a nurse call button. I could not shout,as a result of the stroke I could hardly speak and, when I did manage to speak, it was barely intelligible. Needing assistance, I improvised and used the bed control pendant to bang on the bed frame. The unorthodox communication technique worked in that it got attention but I was scolded (banging was ‘inconsiderate of other patients’) and I had the bed control taken away and moved out of my reach! However, the nurse did give me the nurse call button but it was at the cost of losing my bed control. Ensure the Client always has an acceptable means of summoning assistance. Never punish a Client by removing control. The removal of a Patient's control is the removal of a Patient's dignity. When hoisting, ensure the hoist is in good working order (Health and Safety Executive 2011; Bainbridge 2019). If the Client is capable, put control of the hoist in the Client’s hands. Give control of the hoist to the person to be hoisted. The Carers can ensure that hoisting is undertaken safely even when they are not directly holding the hoist control. If the individual is physically and cognitively competent, the role of the Carer is to empower the Client and enable him / her to do it for him / herself. If there is no other option but for Carers to operate the hoist, it is important that they allow the Client to take charge of the situation by asking the person to give instructions on what actions to take and when to take them. Client instructions need not be verbal, sign or gesture are equally as good; these modes of communication still allow the Client control of the situation. Do not take control away from the Client, allow the Client gradually to take control away from you. The goal is control. Client control. Who is in charge in such situations? (Haug & Lavin 1981; Veatch 2008) A Carer entered my room while I was watching a film. She took the TV remote off my bed and paused the film without asking. I was somewhat annoyed! Her actions implied that she was in charge of the situation and, now that she was present, I was subject to her will. The question of who is in ultimate control of a situation can be contentious. If a Client is saying one thing and the Client’s spouse (or Significant Other) another and the Carer’s belief is yet a further option, whose rule is correct? Sometimes this can be problematic. As a general principle, the Client should always have the guiding voice, although it may prove very difficult to ignore the spouse! Suppose the Client is not cognitively competent, should the spouse’s wishes prevail? The answer is not a simple ‘yes’. The Client’s wishes should always be a priority but an other’s wishes may overrule a Client if the Client’s wish is D.U.B.I.O.U.S: - Dangerous,

- Unreasonable (impartial others would judge it to be so),

- Bad (for the Client), (who decides what is bad for the Client?!)

- Impossible to undertake,

- Outside your remit, (there may be rules that do not permit Carers to perform specific actions. This includes any directive written into the Client’s Care Plan),

- Unintelligible or Unworkable,

- Specialist (requires a professional – a person specifically qualified for that role).

- Choice is a voice. Always give the Client a choice (Dixon, Robertson et al 2010; Mulley, Trimble, & Elwyn 2012) but don’t constrain the Client to choices that Carers find acceptable: don’t ask,

“Would you like tea or coffee?”

rather ask,

”Would you like tea or coffee or something else?”.

Adding ‘or something else’ makes possible a choice that puts the client in control. Of course, multiple options within a single question posed to a person without any means to communicate is, in itself, problematic. It is easily solved by presenting the options, one at a time, allowing the person to respond ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to each. If the person responds affirmatively to ‘something else’, you have the further issue of discovering which of all available drinks the person wants. However, that task is not so arduous as it might appear. The person is in a room within a building and there will be a finite number of drinks available. Once you get to know a person, you will also get to know the person’s preferences. Presenting personal preferences prioritising previously picked options will likely quickly reach a choice. Provision of real choice puts the individual in control and gives the person a voice.

• People think that they have the right to make decisions on my part for choices in my life. Again, taking over control and taking it away from me. You do not have the right to take control of another person just because they have an issue with communication or a learning difficulty. Ways must be found to involve the individual in her / his life choices, no matter how difficult that may be. My Carers were cleaning my bottom. I was screaming in pain. Eventually, I said, “stop please stop.” Over and over again. Did they stop? No, they continued cleaning my bottom despite my obvious distress. They took the decision to continue saying things to justify their actions, “we have got to get you clean otherwise you will be in more pain” and, “sorry just a little longer”, “nearly finished”, “almost there”, while I was begging them to stop. My decision was ignored, they took the decision for me.

Bibliography and References

Bainbridge, L. (2019) .A Complete Guide on How to Use a Hoist Correctly https://www.beaucare.com/blog/a-complete-guide-on-how-to-use-a-hoist-for-correctly/

Bryen D.N. (1993) Augmentative Communication Mastery: One approach and some preliminary outcomes. The First Annual Pittsburgh Employment Conference for Augmented Communicators Proceedings. August 20-22: Shout Press: Pittsburgh

Dickerson, L. (1995) Techniques for the integration of people who use alternative communication devices in the workplace. 3rd Annual Pittsburgh Employment Conference. pp. 27 - 34. Pittsburgh: Shout Press

Dixon, A., Robertson, R., Appleby, J., Burge, P., Devlin, N., & Magee, H. (2010). Patient choice: how Patients choose and how providers respond. London: The King’s Fund. Available at: www.kingsfund.org.uk/ publications/Patient-choice

Dunbar, R. (1996) Grooming, gossip and the evolution of language. Faber and Faber ISBN 0-571-17396-9

Haug, M., & Lavin, B. (1981). Practitioner or Patient - Who's in Charge? Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, Volume 22(3), pp. 212-229.

Health and Safety Executive (2011) Getting to grips with hoisting people. HSE information sheet; Health Services Information Sheet No 3. This document is available at www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/ hsis3.pdf.

Hogg, G., & Wilson, E. (2004) Does he take sugar? The disabled consumer and identity. In British Academy of Management Conference Proceedings. St. Andrews, Scotland.

Jeffree, D., & McConkey, R. (1976) Let me speak. London: Human Horizons Series: Souvenir Press

Jones, A.P. (1996) Impact. Liberator Ltd. Swinstead, Lincolnshire.

Joseph, D. (1986) The morning. Communication Outlook. Volume 8 (2), Page 8

Katamba, F. (1994) English Words. London and New York: Routledge

Light, J., McNaughton, D., & Parnes, P. (1986) A protocol for the assessment of the communicative interaction skills of nonspeaking severely handicapped adults and their facilitators. Toronto: Hugh Macmillan Medical Centre

Mulley, A., Trimble, C., & Elwyn, G. (2012). Patients’ preferences matter: stop the silent misdiagnosis. London: The King’s Fund. Available at: www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/Patients-preferencesmatter

Oakley, M. (1991) Quoted in ‘The Hidden Handicap’ by Darby, S. Times Educational Supplement (No.3930) October 25 1991 page 38

Pinker, S. (1994) The language instinct. First published by William Morrow and Co. Penguin Press: ISBN 0-14-017529-6

Sacks, O. (1989) Seeing Voices University of California press. Picador Edition (1991) ISBN 0-330-31716-4

Sienkiewicz-Mercer, R. & Kaplan, S.B. (1989) I raise my eyes to say yes. Houghton Mifflin

Veatch, R.M. (2008) Patient, Heal Thyself: How the New Medicine Puts the Patient in Charge, Oxford University Press

Wagner, M.G. (1991). Does he take sugar? World health forum; Volume 12(1) : pp, 87 - 89 https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/49206

Wittgenstein, L.J.J. (1953) Philosophische Untersuchungen. English Translation by Ainscombe G. Oxford University Press 1958.

Bainbridge, L. (2019) .A Complete Guide on How to Use a Hoist Correctly https://www.beaucare.com/blog/a-complete-guide-on-how-to-use-a-hoist-for-correctly/

Bryen D.N. (1993) Augmentative Communication Mastery: One approach and some preliminary outcomes. The First Annual Pittsburgh Employment Conference for Augmented Communicators Proceedings. August 20-22: Shout Press: Pittsburgh

Dickerson, L. (1995) Techniques for the integration of people who use alternative communication devices in the workplace. 3rd Annual Pittsburgh Employment Conference. pp. 27 - 34. Pittsburgh: Shout Press

Dixon, A., Robertson, R., Appleby, J., Burge, P., Devlin, N., & Magee, H. (2010). Patient choice: how Patients choose and how providers respond. London: The King’s Fund. Available at: www.kingsfund.org.uk/ publications/Patient-choice

Dunbar, R. (1996) Grooming, gossip and the evolution of language. Faber and Faber ISBN 0-571-17396-9

Haug, M., & Lavin, B. (1981). Practitioner or Patient - Who's in Charge? Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, Volume 22(3), pp. 212-229.

Health and Safety Executive (2011) Getting to grips with hoisting people. HSE information sheet; Health Services Information Sheet No 3. This document is available at www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/ hsis3.pdf.

Hogg, G., & Wilson, E. (2004) Does he take sugar? The disabled consumer and identity. In British Academy of Management Conference Proceedings. St. Andrews, Scotland.

Jeffree, D., & McConkey, R. (1976) Let me speak. London: Human Horizons Series: Souvenir Press

Jones, A.P. (1996) Impact. Liberator Ltd. Swinstead, Lincolnshire.

Joseph, D. (1986) The morning. Communication Outlook. Volume 8 (2), Page 8

Katamba, F. (1994) English Words. London and New York: Routledge

Light, J., McNaughton, D., & Parnes, P. (1986) A protocol for the assessment of the communicative interaction skills of nonspeaking severely handicapped adults and their facilitators. Toronto: Hugh Macmillan Medical Centre

Mulley, A., Trimble, C., & Elwyn, G. (2012). Patients’ preferences matter: stop the silent misdiagnosis. London: The King’s Fund. Available at: www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/Patients-preferencesmatter

Oakley, M. (1991) Quoted in ‘The Hidden Handicap’ by Darby, S. Times Educational Supplement (No.3930) October 25 1991 page 38

Pinker, S. (1994) The language instinct. First published by William Morrow and Co. Penguin Press: ISBN 0-14-017529-6

Sacks, O. (1989) Seeing Voices University of California press. Picador Edition (1991) ISBN 0-330-31716-4

Sienkiewicz-Mercer, R. & Kaplan, S.B. (1989) I raise my eyes to say yes. Houghton Mifflin

Veatch, R.M. (2008) Patient, Heal Thyself: How the New Medicine Puts the Patient in Charge, Oxford University Press

Wagner, M.G. (1991). Does he take sugar? World health forum; Volume 12(1) : pp, 87 - 89 https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/49206

Wittgenstein, L.J.J. (1953) Philosophische Untersuchungen. English Translation by Ainscombe G. Oxford University Press 1958.