3. Selecting Vocabulary for Communication Books & Boards

Click on your browser back arrow, or the image left, or use the return arrow at the bottom of this page to return to the Main Creating Communication Books and Boards web page.

Vocabulary and symbol selection are on-going processes

Burkhart L. 1990 page 10

What is vocabulary selection?

Vocabulary selection can be viewed as the process of choosing a small list of appropriate words or items from a pool of all possibilities

Yorkston K., Dowden P., Honsinger M. , Marriner N., & Smith K. 1988 page 189

How do we select the vocabulary that is to be contained within an individual Learner’s communication system?

The selection of vocabulary for augmentative communication systems is one of the most important tasks facing AAC teams.

The communication success of the augmentative communicator will be determined, in part, by this vocabulary.

Morris K. & Newman K. 1993 page 85

Just how much vocabulary is sufficient?

Along with training issues, this presentation will focus on one area that can make or break a student’s success in mainstream education - the acquisition and control of language and vocabulary. It is critical that students included in mainstream education have access to a substantial amount vocabulary organized in a manner that promotes timely interaction and linguistic transparency

Van Tatenhove G.& Vertz S. 1993 page 128

A second reason for the board’s ineffectiveness was that Dawn’s vocabulary was much larger than the board could accommodate. This reinforced her belief that speech was more dependable: "The board doesn’t have the right stuff. It doesn’t have enough words to say what I want to say. It’s hard to use it when there are things you want to say and nothing is there. I might as well use my speech and take my

chances."

Smith-Lewis M. & Ford A. 1987

What about the development of linguistic skills?

AAC systems should support children’s developing language knowledge and skill. The topics, words, and phrases selected for use in children’s AACsystems must not only reflect current language abilities but also allow children to learn and use language forms that reflect

their evolving cognitive, semantic, syntactic, and pragmatic development.

Marvin C., Beukelman D., Brockhaus J., & Kast L.. 1994

Who is to make such decisions and what qualifications do they have to undertake this task?

Indeed, vocabulary selection during natural speech and written communication interactions is so automatic that most AAC specialists themselves have little experience selecting vocabulary items in advance of the act of speaking or writing. Even professionals who have regular contact with persons who experience communication disorders such as stuttering, voice problems, articulation problems, and cleft palate rarely need to pre-select messages to support conversational or written communication.

Beukelman D. & Mirenda P. 1992 page 159

There is always a danger that, in selecting vocabulary for an individual and without the individual’s input, elements are selected on the basis of the usefulness to Significant Others and not to the individual. Items, such as expletives, may be considered in very bad taste and simply left out. 'Yes I will' may be included but 'No I won’t' may not. It is important to be wary not to exercise some form of unconscious social control through the selection of 'positive' vocabulary elements.

Listen to me, angel tot,

Whom I love an awful lot ...

When I praise your

speech with glee

And claim you talk as well as me,

That’s the spirit, not the letter.

I know more words and say them

better.

Ogden Nash , ‘Thunder over the nursery’

Whom I love an awful lot ...

When I praise your

speech with glee

And claim you talk as well as me,

That’s the spirit, not the letter.

I know more words and say them

better.

Ogden Nash , ‘Thunder over the nursery’

How many words do children know?

Estimates of the personal vocabulary size of an individual at any point in his or her development vary enormously. Iit depends on what counts as a word and whether we are talking about expressive or receptive vocabularies. Pinker (1994) estimates that an average American high school graduate knows between 45,000 and 60,000 ‘listemes’ (the Di Sciullo A. & Williams E. 1987 definition of a word or word group root that has to be committed to memory and whose meaning cannot be deduced from its parts). Nagy & Anderson (1984) and Nagy & Herman (1987) estimate the reading vocabulary of an average American student at 40,000 words. However, Miller (1991) raises this figure to 60,000 - 80,000 if proper nouns and other expressions are included. Seashore& Eckerson (1940) calculated that the average adult knows 150,000 words (a word being defined as an item listed in the 1937 edition of Funk and Wagnell’s New Standard Dictionary of the English Language. See Aitchison J. 1994 and Pinker S. 1994 for descriptions of the methodologies used in such calculations) of which approximately 60,000 were basic words and 96,000 were derivations and compounds of these words. They suggested that the average adult actively uses 90% of their vocabulary store. However, when asked to estimate their vocabulary size people incorrectly guess at between 1% and 10% of the correct amount (Seashore R. & Eckerson L. 1940). Note that the figure of 60,000 keeps appearing. However, with the wide fluctuations in estimates of the size of cerebral lexicons, the figures quoted in texts should be not be treated as the final word in this matter (pun intended!). For example:

We can estimate that an average six-year-old commands about 13,000 words (Pinker S. 1994)

At two years of age the average vocabulary is 300 words. By the age of five it is five thousand. By twelve it is about 12,000 (Boutell J.,

Guardian, 12 August, 1986)

In English, there are about 500,000 words. About 20,000 of them are considered 'common' and used by everyday people. By the time speaking children are two years old, they use about 2,000 different words in a single day. By age ten, they might use as many as 5,000 - 7,000 different words in a single day. (Van Tatenhove G. 1994 with references to: 1 Odgen C. (1968); 2 Crystal D. (1986 - ISAAC in chains))

Compare these totals with the vocabulary of any of the ‘talking apes’, animals who have been taught a language-like system in which signs stand for words. The chimps Washoe and Nim actively used around 200 signs after several years of training, while Koko the gorilla supposedly uses around 400. None of these animals approaches the thousand mark, something which is normally achieved by children soon after the age of two. (Aitchison J. 1994 page 7)

Children pick up words like a magnet picks up pins - possibly over ten a day. Estimates vary as to vocabulary size at each age. On average, a two-year-old actively uses around 500 words, a three-year-old over 1,000, and a five-year-old up to 3,000. And this is far fewer than the number of words which can be understood. The passive vocabulary of a six-year-old has been estimated at 14,000 by one researcher. (Aitchison J. 1994 page 169)

A human baby produces its first real words at about eighteen months of age. By the age of two, it has become quite vocal and has a vocabulary of some fifty words. Over the next year it learns new words daily, and by the age of three it can use about 1000 words. ... Then the floodgates open. By the age of six, the average child has learned to use and understand around 13,000 words; by eighteen it will have a working vocabulary of about 60,000 words. (Dunbar R. 1996 page 3)

It has been estimated that a child must be learning new words at a rate of up to ten a day or, put another way, a new word every ninety waking minutes (Carey S. 1978; Ingram J. 1992; Jackendoff R. 1993 page 103; Aitchison J. 1994 page 169; Pinker S. 1994; Dunbar R. 1996 page 3)(although Miller G. & Gildea P. 1987 page 86 suggest 13 words and Chomsky N. 1988 page 27 suggests 12).

The standard estimate is that a five-year-old knows on the order of 10,000 words. This means that between the ages of two and five (three years, about a thousand days), the child has averaged ten new words a day, or close to one every waking hour! Since a word may take a period of time to master, this also means the child is probably working on dozens of words at a time. (Jackendoff R. 1993, page 103)

... normal children certainly have several thousands of words which are in some sense in their vocabulary by the age of five. (Donaldson M.

1987)

Smith’s study of the expressive vocabulary size of children (Smith M. E. 1926) detailed an increase from 1 word at 8 months to 272 words at 2 years, 896 at 3 years, and 1222 words at 42 months and to 2072 at five years. The five-year-old figure was supported by Jagger’s study (Jagger J. 1929) although by Watts’ (Watts A. 1944) calculations this figure is reached by most children at least a year earlier. Nice (Nice M. 1926) tabulated forty-seven published vocabularies of two-year-olds and found reported vocabularies varying between 5 and 1212 words with an average of 328. By 30 months the ranges had increase to between 30 to 1509 words with an average of 690. Von Tetzchner & Martinsen state that 2 to 3-year-olds have at least 1,000 words (three times the size of Bouttell’s estimate) at their command (Von Tetzchner S. & Martinsen H. p.182 1992). While I am personally inclined to agree with the Von Tetzchner figure, one thing is certain - a child’s seemingly effortless acquisition of language is truly amazing.

It is clear, I hope, that, by five years of age, the average child, and not necessarily the son or daughter of a linguistics professor, knows and is able to use many thousands of words. How can we hope to include all of these words in a communication system?

We can estimate that an average six-year-old commands about 13,000 words (Pinker S. 1994)

At two years of age the average vocabulary is 300 words. By the age of five it is five thousand. By twelve it is about 12,000 (Boutell J.,

Guardian, 12 August, 1986)

In English, there are about 500,000 words. About 20,000 of them are considered 'common' and used by everyday people. By the time speaking children are two years old, they use about 2,000 different words in a single day. By age ten, they might use as many as 5,000 - 7,000 different words in a single day. (Van Tatenhove G. 1994 with references to: 1 Odgen C. (1968); 2 Crystal D. (1986 - ISAAC in chains))

Compare these totals with the vocabulary of any of the ‘talking apes’, animals who have been taught a language-like system in which signs stand for words. The chimps Washoe and Nim actively used around 200 signs after several years of training, while Koko the gorilla supposedly uses around 400. None of these animals approaches the thousand mark, something which is normally achieved by children soon after the age of two. (Aitchison J. 1994 page 7)

Children pick up words like a magnet picks up pins - possibly over ten a day. Estimates vary as to vocabulary size at each age. On average, a two-year-old actively uses around 500 words, a three-year-old over 1,000, and a five-year-old up to 3,000. And this is far fewer than the number of words which can be understood. The passive vocabulary of a six-year-old has been estimated at 14,000 by one researcher. (Aitchison J. 1994 page 169)

A human baby produces its first real words at about eighteen months of age. By the age of two, it has become quite vocal and has a vocabulary of some fifty words. Over the next year it learns new words daily, and by the age of three it can use about 1000 words. ... Then the floodgates open. By the age of six, the average child has learned to use and understand around 13,000 words; by eighteen it will have a working vocabulary of about 60,000 words. (Dunbar R. 1996 page 3)

It has been estimated that a child must be learning new words at a rate of up to ten a day or, put another way, a new word every ninety waking minutes (Carey S. 1978; Ingram J. 1992; Jackendoff R. 1993 page 103; Aitchison J. 1994 page 169; Pinker S. 1994; Dunbar R. 1996 page 3)(although Miller G. & Gildea P. 1987 page 86 suggest 13 words and Chomsky N. 1988 page 27 suggests 12).

The standard estimate is that a five-year-old knows on the order of 10,000 words. This means that between the ages of two and five (three years, about a thousand days), the child has averaged ten new words a day, or close to one every waking hour! Since a word may take a period of time to master, this also means the child is probably working on dozens of words at a time. (Jackendoff R. 1993, page 103)

... normal children certainly have several thousands of words which are in some sense in their vocabulary by the age of five. (Donaldson M.

1987)

Smith’s study of the expressive vocabulary size of children (Smith M. E. 1926) detailed an increase from 1 word at 8 months to 272 words at 2 years, 896 at 3 years, and 1222 words at 42 months and to 2072 at five years. The five-year-old figure was supported by Jagger’s study (Jagger J. 1929) although by Watts’ (Watts A. 1944) calculations this figure is reached by most children at least a year earlier. Nice (Nice M. 1926) tabulated forty-seven published vocabularies of two-year-olds and found reported vocabularies varying between 5 and 1212 words with an average of 328. By 30 months the ranges had increase to between 30 to 1509 words with an average of 690. Von Tetzchner & Martinsen state that 2 to 3-year-olds have at least 1,000 words (three times the size of Bouttell’s estimate) at their command (Von Tetzchner S. & Martinsen H. p.182 1992). While I am personally inclined to agree with the Von Tetzchner figure, one thing is certain - a child’s seemingly effortless acquisition of language is truly amazing.

It is clear, I hope, that, by five years of age, the average child, and not necessarily the son or daughter of a linguistics professor, knows and is able to use many thousands of words. How can we hope to include all of these words in a communication system?

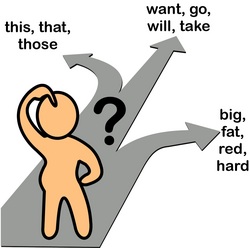

Core Vs Fringe Vocabulary

Core vocabulary is defined as:

The set of lemmas that make up the top 75% of speech when sampled across all environments, by all populations and, at all times (of day).

Research has shown that no matter what the age, occupation, time of day (or other parameter) that people tend to use the same words very frequently. Indeed, 25% of everything that we typically say is made up of just ten lemmas (the, a, and, be, I, in, of, to, that, have). A lemma is a root form; for example, ‘go’ is the lemma (root form) for the words ‘go’, ‘goes’, ‘going’, ‘gone’, ‘went’, and the colloquial forms ‘goer’ and ‘goner’.50% of what we say is made from 100 words and 75% from 1,000. This figure varies for different languages: for example, it has been suggested that Mandarin Chinese has a Core vocabulary of less than 200 words!

Our preliminary findings support the earlier attempts to identify Mandarin Chinese vocabulary using automated approaches or Mandarin Chinese databases. This early data analysis shows that a relatively small number of words (less than 200 words in this sample) will make up 80% of the spoken words used in conversation.These findings are similar to the vocabulary frequency studies in European languages and demonstrate that high frequency words or core vocabulary is consistent across different speakers and topics. (Chen, M.C., Hill, K.J., Yao. T. 2009)

If 75% of all the things we say in everyday speech is comprised of just 1,000 words then, surely, we should be aiming to include these words in any communication system worthy of that name? For listings of the frequencies of words in used in English go here:

http://www.ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/bncfreq/flists.html

However, it may also be reasonably argued that:

- there isn’t enough space for 1,000 entries within the communication system;

- the Learner is not cognitively ready for such a large vocabulary;

- the learner cannot physically access such a large vocabulary.

Even if we were to begin with the top 100 words we would be covering around 30% of everyday communication. With these words we

can create tens of thousands of unique sentences with a requirement only to Learn 100 things.

100 is still too many? A Learner has to begin somewhere and 100 may be a step too far. Could we use just the top ten lemmas?

the, a, and, be, I, in, of, to, that, have

What can a Learner say with these? The answer is not very much! Even though they are very frequently used in conversation they do not produce many everyday sentences/phrases on their own:

I have to, I had to, I have been in that, I had been in that, I have to be,

It is clear therefore that we cannot begin with just the first ten Core Vocabulary words. However if we could mix in a few of the higher frequency FRINGE vocabulary words then the possibilities expand dramatically.

Fringe Vocabulary is defined as that vocabulary which is NOT Core! That is the reminder of all the words in the large OED when the 1,000 Core Lemma forms are removed. The Second Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary contains full entries for 171,476 words in current use, and 47,156 obsolete words. To this may be added around 9,500 derivative words included as subentries. In total 228,132 word headings. If 1,000 (core items) are removed from this, it leaves 227,132 Fringe lemmas! You can see that Fringe Vocabulary easily overwhelms Core.

How do we decide which items of Fringe vocabulary are added into the mix? We could refer to word frequency tables (a web address has been provided earlier). If we did we would find that the earliest noun entries (for example) tend to be those to do with TIME and with PEOPLE. Perhaps we should add these into the mix. If we added just the lemmas ‘time’ and ‘people’ to the earlier ten core words we can now say:

‘I have the time’, ‘a person has been in that’, ‘Am I in time?’ ‘I was in time’. ‘I wasn’t in time’, ‘Aren’t I in time?’, ‘Wasn’t I in time’, ‘Had I the time’, ‘I haven’t the time’, ‘That is the time’, ‘That is the person’, ‘That is a person’, ‘I am a person’, ‘The times are in’, ‘That person is in time’

There are, of course, other ways to decide on what Fringe words to add into the mix. Some suggested strategies for doing this will be covered later in these sections of the web pages

The set of lemmas that make up the top 75% of speech when sampled across all environments, by all populations and, at all times (of day).

Research has shown that no matter what the age, occupation, time of day (or other parameter) that people tend to use the same words very frequently. Indeed, 25% of everything that we typically say is made up of just ten lemmas (the, a, and, be, I, in, of, to, that, have). A lemma is a root form; for example, ‘go’ is the lemma (root form) for the words ‘go’, ‘goes’, ‘going’, ‘gone’, ‘went’, and the colloquial forms ‘goer’ and ‘goner’.50% of what we say is made from 100 words and 75% from 1,000. This figure varies for different languages: for example, it has been suggested that Mandarin Chinese has a Core vocabulary of less than 200 words!

Our preliminary findings support the earlier attempts to identify Mandarin Chinese vocabulary using automated approaches or Mandarin Chinese databases. This early data analysis shows that a relatively small number of words (less than 200 words in this sample) will make up 80% of the spoken words used in conversation.These findings are similar to the vocabulary frequency studies in European languages and demonstrate that high frequency words or core vocabulary is consistent across different speakers and topics. (Chen, M.C., Hill, K.J., Yao. T. 2009)

If 75% of all the things we say in everyday speech is comprised of just 1,000 words then, surely, we should be aiming to include these words in any communication system worthy of that name? For listings of the frequencies of words in used in English go here:

http://www.ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/bncfreq/flists.html

However, it may also be reasonably argued that:

- there isn’t enough space for 1,000 entries within the communication system;

- the Learner is not cognitively ready for such a large vocabulary;

- the learner cannot physically access such a large vocabulary.

Even if we were to begin with the top 100 words we would be covering around 30% of everyday communication. With these words we

can create tens of thousands of unique sentences with a requirement only to Learn 100 things.

100 is still too many? A Learner has to begin somewhere and 100 may be a step too far. Could we use just the top ten lemmas?

the, a, and, be, I, in, of, to, that, have

What can a Learner say with these? The answer is not very much! Even though they are very frequently used in conversation they do not produce many everyday sentences/phrases on their own:

I have to, I had to, I have been in that, I had been in that, I have to be,

It is clear therefore that we cannot begin with just the first ten Core Vocabulary words. However if we could mix in a few of the higher frequency FRINGE vocabulary words then the possibilities expand dramatically.

Fringe Vocabulary is defined as that vocabulary which is NOT Core! That is the reminder of all the words in the large OED when the 1,000 Core Lemma forms are removed. The Second Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary contains full entries for 171,476 words in current use, and 47,156 obsolete words. To this may be added around 9,500 derivative words included as subentries. In total 228,132 word headings. If 1,000 (core items) are removed from this, it leaves 227,132 Fringe lemmas! You can see that Fringe Vocabulary easily overwhelms Core.

How do we decide which items of Fringe vocabulary are added into the mix? We could refer to word frequency tables (a web address has been provided earlier). If we did we would find that the earliest noun entries (for example) tend to be those to do with TIME and with PEOPLE. Perhaps we should add these into the mix. If we added just the lemmas ‘time’ and ‘people’ to the earlier ten core words we can now say:

‘I have the time’, ‘a person has been in that’, ‘Am I in time?’ ‘I was in time’. ‘I wasn’t in time’, ‘Aren’t I in time?’, ‘Wasn’t I in time’, ‘Had I the time’, ‘I haven’t the time’, ‘That is the time’, ‘That is the person’, ‘That is a person’, ‘I am a person’, ‘The times are in’, ‘That person is in time’

There are, of course, other ways to decide on what Fringe words to add into the mix. Some suggested strategies for doing this will be covered later in these sections of the web pages

|

With the inclusion and use of Core Vocabulary we can begin to use ‘language’ almost from day one. If we start with just a page of nouns then that is not possible. Even if we were to begin with just a one-word communication system we could build in the language component. Let’s consider a fictitious young Learner; we will call him Jon. When we study Jon we find out he is really motivated by chocolate! We therefore decide to provide him with a means to ask for his favourite snack. We arrange it so that another member of the staff uses the symbol in front of Jon to request a piece of chocolate. Jon is ‘permitted’ to view the member of staff being rewarded for using the symbol with a small piece of his favourite snack. The member of staff may have to do this a few times before Jon gets the idea! It is hoped that Jon will be motivated to use the symbol to make the request himself. If he does, then he is rewarded with a small piece of chocolate. There are two provisos to this example:

|

- we must use the smallest piece of chocolate that is still motivational to Jon (Half a chocolate button for example);

- we must limit the amount of the above that is available within a specific time frame.

It is not our intention to make Jon sick after eating so much chocolate he can barely move! The chocolate is simply the motivator in teaching the use of the symbol as a means of communicating. Therefore, we need to establish the smallest amount possible we can give in response to a request that still remains a motivational force.

It is important that we set limits otherwise Jon will be asking for chocolate over and over again. Thus, we can place pre-pare the scene and have a packet of chocolate buttons ready-opened that just contains (for example) six pieces. These are tipped onto a paper plate in Jon’s sight and the packet is shaken emphatically to demonstrate that is completely empty. Thus, Jon now can see (he still may not understand) that there are only six pieces of chocolate. As he uses the symbol he can see that a piece of chocolate is removed and the total amount available is reduced. Once he has made six requests the chocolate is gone. Hopefully, he will refrain from requesting any more chocolate! However, let’s assume that he makes another request. The staff member, working with Jon, should show him the empty plate and the empty packet and inform him that there is no more, ‘it has all gone’. However, the staff member can promise to buy/bring some more chocolate the next day (or whatever time period is considered appropriate). Again, during this next time period, the number of chocolate pieces available is as limited. Jon must see and be involved in this process for him to ever come to learn that there is a limit to his requests.

- we must limit the amount of the above that is available within a specific time frame.

It is not our intention to make Jon sick after eating so much chocolate he can barely move! The chocolate is simply the motivator in teaching the use of the symbol as a means of communicating. Therefore, we need to establish the smallest amount possible we can give in response to a request that still remains a motivational force.

It is important that we set limits otherwise Jon will be asking for chocolate over and over again. Thus, we can place pre-pare the scene and have a packet of chocolate buttons ready-opened that just contains (for example) six pieces. These are tipped onto a paper plate in Jon’s sight and the packet is shaken emphatically to demonstrate that is completely empty. Thus, Jon now can see (he still may not understand) that there are only six pieces of chocolate. As he uses the symbol he can see that a piece of chocolate is removed and the total amount available is reduced. Once he has made six requests the chocolate is gone. Hopefully, he will refrain from requesting any more chocolate! However, let’s assume that he makes another request. The staff member, working with Jon, should show him the empty plate and the empty packet and inform him that there is no more, ‘it has all gone’. However, the staff member can promise to buy/bring some more chocolate the next day (or whatever time period is considered appropriate). Again, during this next time period, the number of chocolate pieces available is as limited. Jon must see and be involved in this process for him to ever come to learn that there is a limit to his requests.

|

Once Jon has mastered the use of the chocolate symbol, we can step up the level! We can now add a second symbol ‘want’ and again, another member of staff can be used to model the desired behaviour (want chocolate). The process is then identical to that which was described earlier. However, Jon now is expected to combine two symbols to get to his favourite snack. What if he gets the symbols in the wrong order? It does not really matter at this stage; he is combining two symbols! That is a big step forward. We can help him with the order later. What if he continues to say just ‘chocolate’? We can ‘act stupid’ and pretend that we think he is just telling us that there is some chocolate “Yes, Jon, It’s chocolate” but then we can add “Do you WANT some CHOCOLATE Jon?” Indicating what he must do to now achieve his goal. If this still isn’t working, we can ask the modelling staff member to pop back and demonstrate the correct technique for Jon to view as many times as is necessary. Hand-under-hand prompting should be a last resort if all other avenues have failed. Always begin with the least intrusive prompts before proceeding to those that make actual physical contact UNLESS there is GOOD reason to do otherwise. Once the two word/symbol level has been achieved, we can add a further symbol into the mix, We can now say ‘I want chocolate’ and, eventually, we hope that Jon will be able to say this too! However, you would be right in saying that Jon might be just following the example without any real understanding of the parts of speech involved. Of course he might! In fact, it is very likely! However, if he is using the symbols in the correct order (even if they are sometimes mixed up) that might How do we go on to establish whether Jon has an understanding of the concepts being used and to provide that understanding if it is found that there is none? That is not the purpose of this section of the Sure Start Sheets: this will be covered in the teaching sections. |

Early inclusion of Core vocabulary is recommended with additional group and personal (motivational) Fringe vocabulary added into the

mix. Even if we can are beginning with a very limited number of locations we can include core vocabulary.

mix. Even if we can are beginning with a very limited number of locations we can include core vocabulary.

Should we be providing sentences rather than words?

... but as long as the individual is in an early stage of language development, the use of ready made sentences is not recommended. Single words may be interpreted in more ways than a sentence and will therefore provide more communicative opportunities ... The strategies for combining signs to form sentences are also based on single words, and the use of ready-made sentences may hinder the individual’s learning of the sentence making process. (Von Tetzchner S. & Martinsen H. 1992)

it is only with a word based system that conversation can become flexible enough to allow for true social interaction. (Morrris K. & Newman K. 1993 page 89)

In the field of AAC, much emphasis has been placed on the use of pre-programmed sentences to promote fast and efficient communication among nonspeaking children. However, Nelson’s (1992) information would suggest that dependence on full sentence production is not facilitating a child’s ability to understand single word meanings, word relationships, and altered meanings... For augmented communicators, there is a place for the use of pre-stored sentences and phrases to teach children the power of communication and allow for timely interaction; however, language and lexicon development may not occur when a child’s lexicon remains exclusively or primarily sentence and phrase based. (Van Tatenhove G. 1993b)

Augmented communicators need to be able to create their own novel utterances. It is my personal belief that the ability to create novel

utterances is as important for people with significant, cognitive impairments as it is for augmented communicators with college degrees. (CREECH R. 1995 page 12)

The answer to this question is clearly ‘No’. While there is a place for well-crafted generic sentence and phrasal forms in any communication system, the main body of vocabulary should be individual words that allow the Learner to build any phrase that s/he desires.

The sort of sentences that should be included will consist of:

- Every day (not everyday) sentences: that is, sentences that the Learner will use at least daily ( for example: ‘Hello, how are you?’,

‘I need to go to the bathroom’, A pint of beer and a packet of peanuts, will you adjust my waist strap for me please ...) While we

may think it necessary to provide phrases such as ‘I’d like a cup of tea with milk and two sugars please’, ask yourself how many

times you have actually said something like that? When people ask you if you’d like a drink, your typical response is probably ‘tea,

please’. You may occasionally say ‘Oh, I’d love a cup of tea’but that would not typical. Ensure that any stored phrase is used

frequently. Otherwise, it is occupying a valuable location that could be better used by an additional single word. If an everyday

sentence can easily be spoken in a couple of words then it is probably better not to include it. However, while I could probably ask

for the bathroom just by saying ‘toilet’ or ‘bathroom’, it is not deemed to be very polite to do so and therefore the phrasal from would

be a better choice.

- Starter phrases: these are the opening parts of sentences that can be finished easily with a few additional words

(I want to ..., Can I have ..., Will you get me)

- Idioms and expressions: On the face of it, Come to think of it, Up to my neck in it at the moment, By the way, On the other hand,

If you say so, Far be it from me, Put your foot down, You don’t say! Well, I never did! Get out of here! That’s real cool dude (or

whatever the current vernacular being used is!). Those idioms and expressions that are typically used by verbal peers and mark

an individual as part of a group are particularly important. These may change fairly regularly and so it is a good strategy to

considering updating communication systems on a regular time interval. If Memory cells are used then it is simply a matter of

recording over the outgoing ‘in-phrase’ with the new ‘up-and-coming’ phrase; a process that takes but seconds.

- Conversation Initiators and terminators: can I have a word with you?, What are you doing?, Well, It was lovely to see you but I

have got to be going now, It was great catching up with your news... see you again soon I hope. I am going to be late ...

- Comments: That’s brilliant! I didn’t know that! That’s a surprise! Oh shut up! What a load of rubbish! Don’t be so stupid!

- Getting the goods: Hi, I need to speak with you urgently, Yes, mine’s a pina colada with a twist of lemon and just a dash of ...

- Just joking: Do you know any good single word jokes? Of course, it is possible (and sometimes, in the teaching situation,

desirable) to tell a joke a word at a time but it may lose something in the telling.

- Long live lectures: Stephen Hawking would be at a disadvantage giving presentations word by word with his AACsystem.

- Presenting, poems, and playacting: Acting in a play, presenting the scout pledge, speaking a poem.

- Typical telephone talk: Who is it? What do you want? Hi, it’s Tony here. Can I help you?

- Speed Matters: A Learner trying to communicate with a person passing in a corridor may not command their attention by using

words to produce“Hello, have you got time to stop and talk to me about something?” By the time the first word is uttered, the

conversation partner may have responded with a cheery “Hello” and be moving rapidly towards the exit at the end of the corridor.

Had a full sentence been uttered (for example, “I need to speak with you”) the conversational partner may have stopped and

chatted and, thus, reinforced the Learner’s initiating remark.

The key point here is that these vocabulary choices must be frequently used. If they are unlikely to be used frequently do not add them in.

Consider the two sentences which may be among the sentences found on a typical communication board:

“I am too hot”

“I would like a drink of coffee please”

When is the use of one of these sentence forms appropriate? When the person is too hot or when the person would like a drink of coffee are the obvious answers. These are specific circumstances. They may occur on a daily basis and then, again, they may not. The ‘Saliency of Opportunity’ (SO) of any sentence is directly proportional to the frequency with which related events occur. If, for example, a person often feels thirsty and generally prefers coffee, the SO for the phrase ‘I would like a cup of coffee’ is high. However, if the preferred drink is not always coffee then the saliency is lowered. Of course, saliency may be raised by a generic sentence:

“I would like a drink, please”

It would necessitate that the person provide further information about the type of drink required. However, typically, the Significant Others,

with whom the person is most likely to interact, will known the drinks normally consumed and provide a verbal listing from which the individual can select. ‘Basic Need Sentences’ are those for which the saliency of opportunity is high. Where possible the sentence should be analysed to see if the SO can be raised by changing one or more vocabulary aspects: For example, consider the phrase:

“I absolutely detest brussel sprouts”.

While the individual may indeed have an aversion to these vegetables, if the sentence were to be changed to:

“I don’t like that”

then the SO is raised enormously and the phrase becomes more useful as an addition to a communication system. Note that ‘I don’t like that’ is comprised entirely from CORE Vocabulary words. It is a general rule that as the component vocabulary of a phrase approaches CORE status then the SO increases.

Phrase → CORE Then SO ↑

My dog has no nose

↓

My animal has no body part

↓

It has none

Therefore, while we should provide some phrasal entries within communication systems there are a few guidelines to deciding which are to be used:

- Frequency of likely use;

- Saliency of Opportunity;

- CORE vocabulary structure;

- Social acceptance amongst peers (this will affect the earlier points).

Probably the best way to provide phrasal components within boards created using the Voice Symbol software is to use Memory Cells. Please see the pages on the use of Memory Cells for further information.

A word of warning! Limit the use of sentences! It is almost self-evident that, if the human mind did store whole phrasal units, then it would have to be infinitely large, as the number of potential sentences a human may utter is limitless. This point is clearly argued in chapter two of Jackendoff’s (1993) book - ‘Patterns in the mind’:

And so it goes on, giving us 108 x 108 ‘ 1016 absolutely ridiculous sentences. Given that there are on the order of ten billion (1010) neurons

in the brain, this divides out to 106, or one million sentences per neuron. Thus, it would be impossible for us to store them all in our brains ...

In short, we can’t possibly keep in memory all the sentences we are likely to encounter or want to use. (Jackendoff R. 1993 page 12)

The single word, while meeting the base needs of the individual, has the potential to grow into a basic communication system of a couple of

hundred words. To achieve a similar versatility, the sentence format would have to contain hundreds of thousands of forms. The individual would then be required to sift through all the different sentence possibilities (and their encodings) to select the right form for a particular occasion. Evidence from already competent users of communication systems shows that they do not do work in this way.

An argument, which might be raised in opposition to a words-based approach, is that the sentence format models a good syntactic

structure to which an individual may aspire. There are a number of flaws in this argument, for it assumes:

- an individual may best develop syntactic skills through pointing to or selecting sentences;

- the individual is relating to the whole of the sentence and not to a key element (word?) within that sentence (quarrying)

- generating sentences of correct syntactic structures is sufficient for the development of similar structures by an individual with a

delayed or deviant language;

- without practice with elements of a syntax an individual, who has not yet developed age appropriate syntactic skills, may gain

an unconscious understanding of grammar;

- enough sentences may be encoded to give examples of syntax for the Learner to gain an insight;

- the presentation of full syntax (and/or literacy) to the listener is better than functional communication through a words-based approach.

None of the above can be assumed to be true (see, for example, AITCHISON J. 1989; BLOOM P. 1993; JACKENDOFF R. 1993). It may further be argued that the sentence is easier to comprehend than the word (especially for those with a learning difficulty), that it is easier to gain a gestalt of a whole rather than individual elements. However, the conclusions that may be drawn from work with animals (especially apes) would not appear to support this contention.

... but as long as the individual is in an early stage of language development, the use of readymade sentences is not recommended. Single

words may be interpreted in more ways than a sentence and will therefore provide more communicative opportunities ... The strategies for combining signs to form sentences are also based on single words, and the use of ready-made sentences may hinder the individual’s learning of the sentence making process. (Von Tetzchner S. & Martinsen H. 1992)

It is only with a word based system that conversation can become flexible enough to allow for true social interaction.

(Morris K. & Newman K. 1993 page 89)

In the field of AAC, much emphasis has been placed on the use of pre-programmed sentences to promote fast and efficient communication among nonspeaking children. However, Nelson’s (1992) information would suggest that dependence on full sentence production is not facilitating a child’s ability to understand single word meanings, word relationships, and altered meanings... For augmented communicators, there is a place for the use of pre-stored sentences and phrases to teach children the power of communication and allow for timely interaction; however, language and lexicon development may not occur when a child’s lexicon remains exclusively or primarily sentence and phrase based. (Van Tatenhove G. 1993b)

The first issue is whether to select a predominantly word-based message set or a predominantly sentence/phrase-based message set. When comparing the parameters of the flexibility of message composition with the speed of message generation, one is aware of a complex trade-off. Clearly, a word-based vocabulary allows maximum flexibility in the ability to compose novel messages, to compose messages reflecting a variety of semantic-syntactic forms, and to compose message of increasing mean length of utterance. However, in providing this flexibility, the trade-off is reduced speed of message generation. This is particularly seen as the mean length of utterance increases. When composing a message of more than three symbols, the augmented speaker tends to exhibit reduced motivation for lengthier symbol combinations and the speaking partner tends to exhibit reduced patience for waiting for message composition. (Elder P. & Goosens C. 1990 page 34)

There are yet other arguments that would seem to favour the use of a sentence-based approach. It may be argued that sentences are more

likely:

- to be perceived as communicatively competent by a communication partner;

- to guarantee a successful (and therefore more motivational) interchange.

However, In experiments by BEDROSIAN, HOAG, CALCULATOR, & MOLINEUX (1992) and BEDROSIAN, HOAG, JOHNSON, & CALCULATOR (1993) it was shown that, in all but one instance, the aided message length did not have a significant effect on the listener’s

rating of a Learner’s communicative competence. The exception to this finding, in both studies, was when the listener was a Speech and Language Therapist!:

Based on these findings, we suggested that speech-language pathologists should be more accepting of single-word messages by these

individuals in conversations .... (Bedrosian J. 1995)

It would appear that length of utterance is important to people professionally concerned with ability in this area. Why should this be? There

are a number of possible explanations. A speech professional:

- is trained to be more aware of a Learner’s potential and has therefore a greater expectation of competence;

- is more likely to empathise with a Learner and understands that others may react negatively to utterances that are qualitatively

and quantitatively different;

- may see a significant other’s reinforcement of a Learner as contingent upon length of utterance;

- may unconsciously see a Learner’s length of utterance as an indicator of their own competence;

- may be working with lower abilities were sentences are often seen as the most appropriate approach;

- may be new to the field of AAC. Often speech professionals begin with a sentence-based approach and then incorporate words.

While other professionals are concentrating on perhaps more evident aspects of an individual’s disability, the speech professional is concentrating on a hidden aspect - language. They may view others as judging their professional competence on an individual’s improved

ability in this area. The ‘evidence’ of such an improvement is in improved quality and quantity of speech. Do speech professionals unconsciously take on this ‘criteria’ for a judgement of professional competence and apply it to Learners of AAC?

The word is a powerful and versatile vehicle with which to express thought. It has the possibility of contextuality, unique combinations, and its number can grow with the individual. A word-based vocabulary should not only be seen as capable of growing with an individual but actually promoting and aiding that growth in a reciprocal relationship. However, the word form alone in preference to the use of sentences is not necessarily the better solution. The word is a powerful tool in AAC but the use of pre-stored sentences also has many advantages. There is no rule which states it must be one or the other. We can use both. Allow a system to grow with an individual and an individual to grow with a system. Anything else is counterproductive and is not worthy of the name augmented communication.

Speech is an arrangement of notes that will never be played again. F. SCOTT FITZGERALD from‘The Great Gatsby’, Ch. 1 (1925)

In order to maintain some impartiality and to demonstrate there are those who may not totally agree with the word-based approach, this section will end with a quote from a 1995 article:

In the light of this result, it is no longer tenable to claim that a pre-stored text approach to facilitating augmentative communication is

incapable of generating appropriate (from the point of view of an observer) content in free flowing conversation on a fairly broad topic. (Todman J., Elder L., & Alm N. 1995 page 233)

The Inclusion of negative statements

Isn’t the right to freedom of speech seen as a fundamental human right in the majority of all democratic nations? (In the United States, for example, this is safeguarded by the 1st Amendment to the Constitution.) It has even been suggested that chimpanzees are able to swear in sign (See - LINDEN E. 1975 page 8). Why should people be denied their freedom of speech because of a disability? It is not uncommon to hear people say that a particular word or phrase (or song) should be removed from a system because it is offensive, undesirable, unnecessary, unimportant, disruptive, or because it ‘may be used inappropriately’. As Voltaire is supposed to have said:

I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it

(Attributed to VOLTAIRE - See TALLENTYRE S. 907)

As a rule, if a system contains the phrase ‘Yes, I would like to do that’ then it should also contain the opposite, ‘No, I don’t want to do that’. However, isn’t that encouraging a Learner to refuse to co-operate? What if s/he should say it? Well, ask yourself what you would do if their vocal peer should say the same thing? You should respond exactly the same manner! The response should be both identical and appropriate to:

- a verbal peer who uttered a similar remark;

- to the situation.

If a Learner were to swear, the response would depend on the age of the Learner, the situation, and the presence of others. What is acceptable over a drink in a pub might not be acceptable from a junior in a classroom. A comment made in passing may help:

“Tim, I don’t like to hear you use those words. That word (say the word) is swearing (as the Learner may not know, its meaning might be made explicit) and it should only be used with care and thought. Some people would be upset by it. Do you understand what I am saying to you? This is not the time or the place to use that word.”

If Tim continued to use the word the response would be slightly stronger in tone and would become even stronger if this was ignored. At no time should you consider the removal of the word from the system! Can we take such words from the mind’s of verbal peers? Of course, not!

While no-one has any desire to see (or hear) a child utter profanities, I know what I would say if I dropped a house brick on my finger!

Sh... ugar!

I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it

(Attributed to VOLTAIRE - See TALLENTYRE S. 907)

As a rule, if a system contains the phrase ‘Yes, I would like to do that’ then it should also contain the opposite, ‘No, I don’t want to do that’. However, isn’t that encouraging a Learner to refuse to co-operate? What if s/he should say it? Well, ask yourself what you would do if their vocal peer should say the same thing? You should respond exactly the same manner! The response should be both identical and appropriate to:

- a verbal peer who uttered a similar remark;

- to the situation.

If a Learner were to swear, the response would depend on the age of the Learner, the situation, and the presence of others. What is acceptable over a drink in a pub might not be acceptable from a junior in a classroom. A comment made in passing may help:

“Tim, I don’t like to hear you use those words. That word (say the word) is swearing (as the Learner may not know, its meaning might be made explicit) and it should only be used with care and thought. Some people would be upset by it. Do you understand what I am saying to you? This is not the time or the place to use that word.”

If Tim continued to use the word the response would be slightly stronger in tone and would become even stronger if this was ignored. At no time should you consider the removal of the word from the system! Can we take such words from the mind’s of verbal peers? Of course, not!

While no-one has any desire to see (or hear) a child utter profanities, I know what I would say if I dropped a house brick on my finger!

Sh... ugar!

Targetting Small relevant areas of Fringe Vocabulary

While there is a great temptation to include masses of fringe vocabulary into a communication system, it is not necessary. It is very unlikely to be utilised and is not worth the extra effort by staff and the space that it occupiesadds bulk and complexity to the communication system.

The fringe vocabulary that is relevant to a 6-year-old child is unlikely to be the same vocabulary that is relevant to a 16-year-old adolescent. Indeed, the fringe vocabulary for a 16 year-old may be different to the fringe vocabulary suited to another person of the same age. We all have different tastes, experiences, daily routines, knowledge, and command of language. We should expect some differing aspects of fringe vocabularies.That is not to say we cannot or should not teach the same vocabulary to groups of individuals ( a chair is a chair to us al after all). However, the vocabulary should be specifically targeted for the particular group in question.

How do we discover what fringe vocabulary is relevant to a particular Learner?

There are a number of techniques:

Shadowing

Shadowing involves following a Learner through an average day recording all activities and communication interactions. This will

generate lots of information and many ideas for vocabulary tuition but it is a very tiring process for one person to undertake. If the

task can be broken down into stages, such that several people take it in turns throughout the day, the task is made less arduous.

More heads are better than one and the vocabulary list developed may more accurately reflect the needs of the individual. There is

a danger that the day chosen for shadowing the individual is not a particularly active one. Had the next day been selected, the team

might have seen the person interacting at the youth club. Parents too should be involved in the shadowing process. The task should

not be made arduous. Ask the parents to record (either verbally into a micro-recorder or by writing onto prepared sheets) what their

son or daughter is doing on the hour, every hour, through a typical weekend.

It should be stressed that this is a one-off event. They will not be asked to do this every weekend. Typical is highlighted because

there is a temptation to do something special such as taking a trip to Disney Land. What is required is typical vocabulary. It is

inevitable that some parents will record reams and others little. Working through the recorded notes with them will clarify matters

and expand on any recordings that are rather sparse.

This means that time must be spent assessing the environment and finding situations where communication can be used functionally

and that are also suitable for training purposes. (Von Tetzchner S. & Martinsen H. 1992)

Profiles

Profiles are another way of gathering information on a Learner to select the fringe vocabulary that will be introduced early in tuition.

They also help to discover more about a person. A profile is a questionnaire. Questions can cover all aspects of an individual’s life:

Family and friends; favourite items; likes and dislikes; schools, clubs, and events attended; etc.

What are John’s favourite drinks?

What does Susan like to do in the evening?

What are Sam’s favourite TV programmes?

What clubs does Kathy attend?

What is Susan’s taste in music?

Where does John like to go when he goes out?

Profile questionnaires may be developed for staff as well as parents:

What topic is Sam currently studying?

What vocabulary would help Susan to join in with your sessions?

Notebooks

Notebooks record the vocabulary a Learner wishes to say but has no means of making explicit. We have all experienced the

twenty- questions session in which a non-vocal person wants to make a point but others are unable to grasp his or her meaning.

It is to be hoped that, at the end of the twenty question routine, the person’s intent will have been established. This vocabulary

should be recorded. A notebook attached to the back of a wheelchair, or in a pocket on the back of a communication board

(be creative) allows the recording of new vocabulary - which may be neglected otherwise. It is difficult to think of an individual’s

fringe vocabulary needs on the spot. It is likely, as particular situations arise, people will think of new items of vocabulary not

included in the Learner’s original list. The notebook should be the responsibility of one member of the team who should add the

new vocabulary and liaise with tutors for a decision on introducing new symbol(s) to the Learner.

Monitoring Communication

The Learner is already likely to have developed some form of augmented communication system. For example, a person being

introduced to a VOCA may have a Bliss board. A person being introduced to Bliss may use gesture or body language or perhaps

may sign a little. It should be possible to monitor the vocabulary that is used via this system. This will give an idea of what words

and phrases the individual wants to use. These words can then be incorporated into the new system and may be among the first to

be taught.

The fringe vocabulary that is discovered as a result of one or more of the above strategies could be among the first to be taught via the new communication system. In should be noted, however, that teaching already acquired signs and symbol sets is somewhat controversial. Von

Tetzchner and Martinsen (1992) argue that already acquired personal (pages 129 and 144) signs should not be among the first to be taught because:

learning signs to express things the individual is already capable of communicating in other ways may lead to a confusion about their

purpose, and it is more expedient to begin with teaching other signs (Von Tetzchner S. & Martinsen H. 1992)

They give the example (page 144) of a boy who smacks his lips to communicate the word raisin. They argue that, if this is one of the first words chosen to teach the boy, he has to unlearn the already acquired personal sign in favour of the new method of communicating the

same thing. This would rob him of some of the communication skill he has already gained. However, they go on to state that:

In terms of sign or speech teaching, it is similarly easiest to begin with learning signs or words in known situations, where the function of

the signs or words is known (p. 148)

However, how do we know that an individual knows the function of the signs or words?

The question becomes, do we incorporate already acquired signs into teaching the new symbol set or not? The answer must take into account the ability of the individual. Some individuals may easily cope with two ways of expressing the same idea.

There is a further consideration. Suppose a person continues to use an earlier acquired idiosyncratic sign and not the new symbol(s). If the people to whom the person is talking understand the idiosyncratic sign, surely the individual has communicated effectively and this must be accepted. However, if the people are strangers what then? If it is assumed the individual cannot differentiate between those that do understand the idiosyncratic sign and those that do not then the individual is unable to make a conscious decision between the two alternatives. The sign which has a greater recognition value (a word generated through the use of the V-Pen, for example, would be recognised by more people than a word which was signed in ASL, BSL, Makaton, or other) gives the individual a greater potential for independence. If the Learner has the intelligence to discriminate between those that can understand his/her idiosyncratic sign and those that cannot then surely s/he can cope replacing an older less effective symbol for a newer one that is more effective. It will eventually replace or happily co-exist with the idiosyncratic sign. However, the replacements for idiosyncratic signs need not be among the first to be taught. If the Learner is likely to be confused by learning a symbol (set) for an already acquired sign or symbol, it is better to begin with training with other words until the new system naturally takes priority. If the Learner is not likely to be confused, then teaching already acquired signs and symbols in the new form is acceptable.

The fringe vocabulary that is relevant to a 6-year-old child is unlikely to be the same vocabulary that is relevant to a 16-year-old adolescent. Indeed, the fringe vocabulary for a 16 year-old may be different to the fringe vocabulary suited to another person of the same age. We all have different tastes, experiences, daily routines, knowledge, and command of language. We should expect some differing aspects of fringe vocabularies.That is not to say we cannot or should not teach the same vocabulary to groups of individuals ( a chair is a chair to us al after all). However, the vocabulary should be specifically targeted for the particular group in question.

How do we discover what fringe vocabulary is relevant to a particular Learner?

There are a number of techniques:

Shadowing

Shadowing involves following a Learner through an average day recording all activities and communication interactions. This will

generate lots of information and many ideas for vocabulary tuition but it is a very tiring process for one person to undertake. If the

task can be broken down into stages, such that several people take it in turns throughout the day, the task is made less arduous.

More heads are better than one and the vocabulary list developed may more accurately reflect the needs of the individual. There is

a danger that the day chosen for shadowing the individual is not a particularly active one. Had the next day been selected, the team

might have seen the person interacting at the youth club. Parents too should be involved in the shadowing process. The task should

not be made arduous. Ask the parents to record (either verbally into a micro-recorder or by writing onto prepared sheets) what their

son or daughter is doing on the hour, every hour, through a typical weekend.

It should be stressed that this is a one-off event. They will not be asked to do this every weekend. Typical is highlighted because

there is a temptation to do something special such as taking a trip to Disney Land. What is required is typical vocabulary. It is

inevitable that some parents will record reams and others little. Working through the recorded notes with them will clarify matters

and expand on any recordings that are rather sparse.

This means that time must be spent assessing the environment and finding situations where communication can be used functionally

and that are also suitable for training purposes. (Von Tetzchner S. & Martinsen H. 1992)

Profiles

Profiles are another way of gathering information on a Learner to select the fringe vocabulary that will be introduced early in tuition.

They also help to discover more about a person. A profile is a questionnaire. Questions can cover all aspects of an individual’s life:

Family and friends; favourite items; likes and dislikes; schools, clubs, and events attended; etc.

What are John’s favourite drinks?

What does Susan like to do in the evening?

What are Sam’s favourite TV programmes?

What clubs does Kathy attend?

What is Susan’s taste in music?

Where does John like to go when he goes out?

Profile questionnaires may be developed for staff as well as parents:

What topic is Sam currently studying?

What vocabulary would help Susan to join in with your sessions?

Notebooks

Notebooks record the vocabulary a Learner wishes to say but has no means of making explicit. We have all experienced the

twenty- questions session in which a non-vocal person wants to make a point but others are unable to grasp his or her meaning.

It is to be hoped that, at the end of the twenty question routine, the person’s intent will have been established. This vocabulary

should be recorded. A notebook attached to the back of a wheelchair, or in a pocket on the back of a communication board

(be creative) allows the recording of new vocabulary - which may be neglected otherwise. It is difficult to think of an individual’s

fringe vocabulary needs on the spot. It is likely, as particular situations arise, people will think of new items of vocabulary not

included in the Learner’s original list. The notebook should be the responsibility of one member of the team who should add the

new vocabulary and liaise with tutors for a decision on introducing new symbol(s) to the Learner.

Monitoring Communication

The Learner is already likely to have developed some form of augmented communication system. For example, a person being

introduced to a VOCA may have a Bliss board. A person being introduced to Bliss may use gesture or body language or perhaps

may sign a little. It should be possible to monitor the vocabulary that is used via this system. This will give an idea of what words

and phrases the individual wants to use. These words can then be incorporated into the new system and may be among the first to

be taught.

The fringe vocabulary that is discovered as a result of one or more of the above strategies could be among the first to be taught via the new communication system. In should be noted, however, that teaching already acquired signs and symbol sets is somewhat controversial. Von

Tetzchner and Martinsen (1992) argue that already acquired personal (pages 129 and 144) signs should not be among the first to be taught because:

learning signs to express things the individual is already capable of communicating in other ways may lead to a confusion about their

purpose, and it is more expedient to begin with teaching other signs (Von Tetzchner S. & Martinsen H. 1992)

They give the example (page 144) of a boy who smacks his lips to communicate the word raisin. They argue that, if this is one of the first words chosen to teach the boy, he has to unlearn the already acquired personal sign in favour of the new method of communicating the

same thing. This would rob him of some of the communication skill he has already gained. However, they go on to state that:

In terms of sign or speech teaching, it is similarly easiest to begin with learning signs or words in known situations, where the function of

the signs or words is known (p. 148)

However, how do we know that an individual knows the function of the signs or words?

The question becomes, do we incorporate already acquired signs into teaching the new symbol set or not? The answer must take into account the ability of the individual. Some individuals may easily cope with two ways of expressing the same idea.

There is a further consideration. Suppose a person continues to use an earlier acquired idiosyncratic sign and not the new symbol(s). If the people to whom the person is talking understand the idiosyncratic sign, surely the individual has communicated effectively and this must be accepted. However, if the people are strangers what then? If it is assumed the individual cannot differentiate between those that do understand the idiosyncratic sign and those that do not then the individual is unable to make a conscious decision between the two alternatives. The sign which has a greater recognition value (a word generated through the use of the V-Pen, for example, would be recognised by more people than a word which was signed in ASL, BSL, Makaton, or other) gives the individual a greater potential for independence. If the Learner has the intelligence to discriminate between those that can understand his/her idiosyncratic sign and those that cannot then surely s/he can cope replacing an older less effective symbol for a newer one that is more effective. It will eventually replace or happily co-exist with the idiosyncratic sign. However, the replacements for idiosyncratic signs need not be among the first to be taught. If the Learner is likely to be confused by learning a symbol (set) for an already acquired sign or symbol, it is better to begin with training with other words until the new system naturally takes priority. If the Learner is not likely to be confused, then teaching already acquired signs and symbols in the new form is acceptable.

TRVs: Temporarily Restricted Vocabularies

The second vocabulary and language barrier relates to ‘verbal’ classroom participation. All students, at all grade levels, are asked questions, ask questions of others, take oral examinations, and are called upon to recite information. In some classrooms, even shy

students who speak cannot get a word in edgewise. For augmented communicators, the possibilities of well timed speaking is even more remote. The pace of verbal exchanges is too fast to allow even the most efficient student using AAC to participate.

(Van Tatenhove G. & Vertz S. 993 page 129)

A TRV (Temporarily Restricted Vocabulary)(pronounced TREV) is a small subset of the vocabulary that may or may not be contained within any person’s AAC system. It allows a beginner to be involved in an activity on an equal footing with peers.

Trvs can be set up in a variety of ways: either with (typically) fringe words or, alternatively, with phrases:

“That’s right!”

“That’s wrong!”

“I need to think about it”

“I don’t know”

The class are told that they must use one of these phrases in response to the teacher’s questions in the session that will follow. For example, the maths teacher might say:

“If I am facing South and I turn two right angles clockwise. Am I now facing North?”

The pupil has to respond with one of the messages. People using an AAC system can usually access one of the responses in real time on a level footing with their verbal peers. There is a further benefit. In this instance, the messages are a useful addition to the Learner’s vocabulary: they may be used in other lessons and other situations they may encounter:

“Jane you’re 14 now , aren’t you?” “That’s right”

However, it is unlikely that many standard TRVs would be added to or already be a part of the Learner's vocabulary. This is because TRVs are typically comprised of fringe vocabulary.

Other TRV’s might include:

'Tudor' 'Jacobean' 'Stuart'

'heart' 'spleen' 'neuron' 'liver'

'hydrogen' 'helium' 'oxygen' 'nitrogen'

‘I agree’ ‘I don’t agree’ ‘I’m not sure’ ‘I don’t know’

‘True’ ‘False ‘Sometimes’

|

As can be seen from above, TRV’s can be noun sets. For example, a set of materials:

‘cloth’, ‘wood’, ‘metal’, ‘glass’, ‘paper’, ‘plastic’ In this instance, a staff member would require a response from the Learner who would select one of the given materials: “Which material is transparent?” “Which material is used to make books?” “Which material is made from sand?” “Which material is not man-made?” "From which material is this desk made?" "Which one is iron?" "From which one are most clothes made?" |

TRVs should always be contained on an overlay of, at least, two words or phrases. If a person is tested for comprehension, the larger the TRVthe less opportunity of obtaining a right answer by chance alone. At the other extreme, there is a limit to the size of any TRV. Too big a set becomes a sub-vocabulary or a category in its own right and does not allow a user to interact with peers on an equal footing in a classroom interchange. Ideally, a TRV is more than one but less than seven.

|

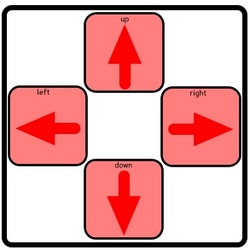

A TRV could be set up to give directions to a staff member in a treasure trail game or a game of hide and seek. For example: ‘Right’, ‘Left’, ‘Forward’, ‘Backwards’, ‘Stop’ ‘Up’, ‘Down’, ‘Right’, ‘Left’ TRVs are ideal for games: Each player starts with one point. Using a pack of cards the user has to state whether the next card is ‘higher’ or ‘lower’ or‘red’ or ‘black’ for a doubling of their points total - OR - ‘hearts’, ‘spades’, ‘clubs’, or ‘diamonds’ to treble their points total. The user may stop at any time by saying ‘stop’. The person with the highest points at the end is the winner. |

The TRVs give control to the augmented communicator with minimum effort and without the need for many hours of vocabulary instruction. Temporarily Restricted Vocabularies:

- allow augmented communicators to participate in lessons on an equal footing with peers;

- answer the requirement of some teachers for access to special vocabulary;

- are not necessarily a part of the Learner’s regular communication system but available for use as and when necessary;

- may be easily spoken in real time; the class is not made to wait for long periods while a user generates a response;

- focus Learner thinking on the answer rather than where a particular word is located in their communication system;

- can ease the pressure felt when asked a question;

- ensure users are not singled out as special - everyone is the same;

- are easy to set up; vocabulary may be quickly added into some systems if generally useful;

- involve subject tutors in the responsibility for the preparation and tuition of new vocabulary;

- are created, kept and maintained by individual tutors. As such tutors understand them;

- do not require many hours of vocabulary tuition before their use;

- may be categorised or themed;

- speed access to vocabulary for switch users;

- allow symbols to be displayed at a larger size to ease selection. If appropriate to do so, these can be added to a Learner's

symbol board at the standard size;

- may be used to teach and test key concepts;

- are best used with all pupils or students in a class or group;

- should be stored into a Learner's communication system only if they are considered of general use;

- should always use the same symbols as in a Learner's communication system (if they are present);

- may be used to engineer the environment;

- take fringe vocabularies out of personal communication systems (PCS); PCS becomes leaner, lighter and easier;

- are always >1 but typically <7.

As suggested above, a TRV may be used to engineer the environment. In this instance, the TRV becomes a permanent or semi-permanent part of the surroundings. For example there are a set of things that may be need to be said while having a bath which are not really needed elsewhere. The TRV for these things could be on the wall by the bath. There are things which are said at meal times which may not be generally needed at other times of the day. These could be displayed on a menu board or on a table menu.

In Summary

Some ideas for the selection of words and phrases to be included in the Starter Vocabulary for an individual Learner or group of Learners are detailed below. Decide on a set of words that:

Realistically represent the current needs of the Learner of the AACsystem.

The needs of different individuals are diverse and a portion of their vocabularies will be unique although there may be much overlap especially within any one frame of reference in any one particular setting. Teaching abstract and non-functional vocabularies is likely to result in frustration for the Learner, a lack of motivation, poor system use, and ultimate failure. The vocabulary chosen must be functional and taught in a functional manner:

For example, matching or naming colour cards has little practical impact on the daily living needs and experiences of a severely developmentally delayed 16-year-old student. However, learning to appropriately match the colours of a shirt and pants he intends to wear to school will have an impact on his social competence. It is of equal importance that functionally relevant communication training must become the standard in intervention programs for AAC users who are developmentally delayed. (Elder P. & Goosens C. 1993 page 34)

Are functional and met daily by the Learner.

Frequency of encounter and of use is important (For frequency & familiarity studies see - HOWES D. & SOLOMAN R. 1951; GOLDIAMOND I. & HAWKINS W. 1958; FORSTER K. & CHAMBERS S. 1973; WHALEY C. 1978; MORTON J. 1979; GERNSBACHER M. 1984; BRADLEY D. & FORSTER K. 1987). Words that are only used once a week (or less frequently) which might be motivating are less useful than words used every day. We tend to remember those which we encounter and use on a daily basis (see references above). The symbols for words and phrases that will be used frequently will be remembered. Indeed, it is likely that their selection will become automatic. Select high frequency words which are functionally important to the Learner and leave others to later if possible. Some words and phrases are important but will not be needed each day- words like doctor and nurse for example. These are functionally important but may not have a high frequency rating. However there is no hard and fast rule which states you cannot introduce low frequency functionally important vocabulary items early in training. Perhaps creative environmental engineering can turn a low frequency functionally important vocabulary item into a temporarily high frequency functionally important vocabulary item. This does not mean injuring a Learner! However, role playing a visit to a doctor, a theme of medicine, asking the nurse to make a daily appearance for a week, and other such creative ideas may help a Learner to work with this vocabulary.

Are within the linguistic and cognitive abilities of the Learner.

Begin teaching words that are simple for the Learner to grasp and to work with: words that are relevant to the Learner’s needs. The easier these are for the Learner to understand, the greater the chance of success with any communication system.

Will be rewarding and motivating for the Learner.

Vocabulary that is motivating to Significant Others is not necessarily motivating for the Learner. That is not to say thisvocabulary should be ignored in the early stages. However, within the starter Vocabulary, there should be more than a sprinkling of words and phrases that are

highly motivating to the Learner.

There is a tendency to select words which are seen as pragmatic within residential situations or those which involve care or nursing. Be wary of this vocabulary because it may not be very motivating for the Learner:

However, in many instances, too much emphasis is given to signs for care, nursing, etc., despite the fact that the individuals themselves seldom talk of these things... the individuals need signs that can be used in a large variety of situations, signs that reflect their interests and make it possible for them to converse about a great number of subjects. (Von Tetzchner S. & Martinsen H.1992)

Allow work to begin on the syntactic and pragmatic structures of language use.

The vocabulary Significant Others initially select for Learners are mostly nouns. First words tend to be the names of things. As soon as is feasible other words should be introduced so that work may begin on syntactic structures and aspects of pragmatics.

Allows the Learner to work in known territory with, in the main, known words.

If the Learner already is communicating using another form of AAC, or uses unaided communication to make his or her wishes known (pointing at a drink for example), these items can be monitored such that the vocabulary-in-use forms the basis for the introduction