AAC INTERCHANGE ISSUES

This page attempts to catalogue and illustrate 20 of the issues that exist in communicative interchanges between the general population and an AAC Speaker. It does not claim to be comprehensive although it will strive to be thorough. If it is your belief that an issue is not feature here, please use the form provided at the foot of this page to get in contact and let us know. If we agree with your claim, we will update the list.

This list has been compiled by AAC Speakers from their experiences with such interchanges. There is no claim that the items are in an order of importance. All are equally valid.

All the images may be enlarged if you click on them. They may not be downloaded from this page. If you would like a cartoon or any image (s), please use the form provided at the foot of this page to make your request.

This page was last updated on January 26th 2023

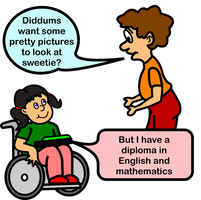

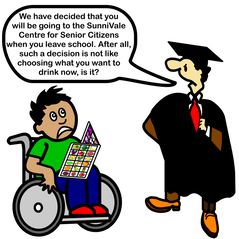

1. Intellectual Assumptions

There is a tendency for others to assume any POD (Person Of Disability) is intellectually deficient and, as such, communicate as with an infant. The suggestion is that you assume intelligence until you have evidence that an other situation is, in fact, the case. The majority of AAC Speakers are not intellectually impaired. Unfortunately, "dumb" meaning an inability to speak carries an alternate meaning of 'lacking in intelligence'. AAC Speakers are not dumb. Far from it! They are able to speak / communicate. AAC Speakers do not have a lack of intellectual perspicuity.

Assumption, by others, that my physical disability equates with a cognitive impairment is reflected in the communication used by others to me as well, particularly by those who do not know me. My Carers often leave me in a worse state than before they arrived. My bottom is sore and very sensitive. Yet, despite my screams of pain, as the Carers clean my bottom, they just say "sorry" and carry on regardless of my feelings doing the same thing in the same way. Even when told to “stop”, I get platitudes like, "nearly finished ", "just a little bit more to do", "I have got to get you clean" and then continuing in wiping me in the same way. As far as I am concerned, when I scream in pain it is a clear indication that I need them to alter the methodology in use and adopt a gentler practice. When I say "Stop! ", I expect them to STOP what they are doing and try a different approach (with my approval). I am not intellectually impaired and I am not an infant in need of direction, I am an intelligent adult and expect to be treated as such. I don't expect to feel worse after the Carers have finished than before they started.I do expect my communication, limited though it is, to be respected and for it not to be ignored.

Assumption, by others, that my physical disability equates with a cognitive impairment is reflected in the communication used by others to me as well, particularly by those who do not know me. My Carers often leave me in a worse state than before they arrived. My bottom is sore and very sensitive. Yet, despite my screams of pain, as the Carers clean my bottom, they just say "sorry" and carry on regardless of my feelings doing the same thing in the same way. Even when told to “stop”, I get platitudes like, "nearly finished ", "just a little bit more to do", "I have got to get you clean" and then continuing in wiping me in the same way. As far as I am concerned, when I scream in pain it is a clear indication that I need them to alter the methodology in use and adopt a gentler practice. When I say "Stop! ", I expect them to STOP what they are doing and try a different approach (with my approval). I am not intellectually impaired and I am not an infant in need of direction, I am an intelligent adult and expect to be treated as such. I don't expect to feel worse after the Carers have finished than before they started.I do expect my communication, limited though it is, to be respected and for it not to be ignored.

2. Personal Space

People assume that it is okay to invade your personal space and choose to communicate in close proximity. This would not be acceptable in 'typical' communicative interactions.

3. Negating Negativity

Being able to communicate means an ability to say "NO". This can be viewed as going too far by the unenlightened. What should you do in response to a refusal to act as requested? How would you react to anyone else who behaved in the same fashion? Do the same! The issue is being unable to accept the inclusion of specific items of vocabulary.

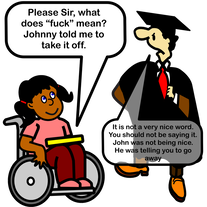

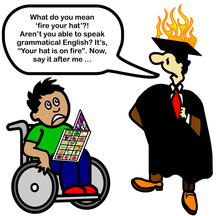

4. Preventing Profanity

Should an AAC Speaker be able to swear? Of course s/he should! However, what if that individual was 7 years old? It's not so clear cut now, is it? At what age does it become acceptable to swear? 10? 15? 18? 21? Never? Different people will have different opinions. At what age is a child that can talk able to swear? As soon as s/he is able to speak! S/he may utter an expletive. There should be no difference. How does the average child learn that it isn't OK to swear? Someone teaches them that it is wrong. Usually an adult provides guidance. Is a five year old able to swear? Of course s/he is! Why don't they? They have learnt that it is not okay to use expletives in certain circumstances. Why should an AAC Speaker be any different? Answer = S/he shouldn't! Provide profanities but engage in expletive explanation. React to their use as you would to any other person of the same age saying the same thing. AAC Speakers have to learn the pragmatics of language use too.

5. Can't Control Communication Completely

The goal is control.

"Handicapped infants may begin to lose interest in a world that they do not expect to control" (Brinker & Lewis, 1982)

"Learned helplessness occurs when it is unclear to the learner that he or she is able to exert control over the environment.....For many learners, their social history has offered few opportunities to self-select desired objects, people, or activities. At meal times plates are prepared and distributed. Additional serving are provided automatically. Coats are handed out and doors opened when it is time to go. Thus, throughout the day, the caregivers do virtually everything for the learners. Initially, some learners may have attempted to self-select items of interest, but were actively encouraged not to do so." (Reichle, J. 1991 p.141)

"When children who are deafblind are young, and especially if they have additional difficulties, they may experience the world as much too large and complicated for them to exercise any control. Their experience may only be of having things done to them, not of doing things for themselves. They may have objects put in front of them to look at, but may not have any choice in the matter." (Wyman 2000 page 82)

"By providing people with PMLD the opportunities to exert control and actively participate we help to facilitate the development of contingency awareness; the knowledge that you are able to have some effect on the environment. ... If we are to prevent individuals either from resorting to self stimulatory behaviours or from withdrawing completely from the external world then it is essential that we ensure they are able to engage with their world in an active and meaningful way." (Hogg 2009. page 20)

While undoubtedly there are a plethora of goals for standard education, and many of these will have equal relevance to those experiencing a disability, there is one particular goal that Talksense believes is a vital component of any curriculum designed to prepare Individuals Experiencing any form of disability for a better quality of future life: that goal is 'control'. Communication provides an individual with a means of control.

"The provision of positive control experiences early in life will be a primary factor in helplessness immunization." (Sweeney, L. 1993)

"a high quality of life is one in which people receive individually tailored support to become full participants in the life of the community, develop skills and independence, be given appropriate choice and control over their lives, be treated with respect in a safe and secure environment”. (Emerson et al 1996)

"Empowerment occurs when control, or power, is passed to an individual or group. In rehabilitation, medicine, social work, psychology, education, and many allied disciplines, it is gradually becoming recognized that the healthiest and most effective individuals have personal control and make decisions for themselves with advice and input from others. The belief here is that, for best results overall, final decisions should be made by the individuals who are most closely affected by the decisions."

(Brown and Brown 2003 page 227)

"Students become empowered by taking control of their own learning." (Sutcliffe 1990 page 13)

"Good quality support is to do with giving people power." (Virginia Moffat 1996 page 37)

Generally speaking, the more independent people are and the less external control they receive from others, the more satisfied they are (higher quality of life) (See Legault 1992).Thus, a fundamental goal of all special education should be equipping Learners to live as independent a life as possible. This has long been recognised:

"... citizens with a mental retardation have a right to receive such individual habilitation as will give each of them a realistic opportunity to lead a more useful and meaningful life and to return to society." (Bannerman, Sheldon, Sherman, & Harchik 1990)

"even children with profound learning difficulties , given suitable conditions provided by modern technology, can make choices; in this case between sounds, voices, and rhymes provided on speakers. Moreover, they show enjoyment while so occupied and are motivated to further choice making. At the beginning of this chapter, the opinion was expressed that every step on the way to having more control over our lives is worth taking. In the case of these children, opportunity to exert control, however limited, appears to be leading to increased motivation and increasing self-regulation." (Beryl Smith 1994)(Page 5)

In order to meet this goal, staff within special education should be developing ways in which more and more control can be passed to Learners. Staff should rarely ever be doing it 'for' (there are some exceptions to this rule) and should hardly ever be doing it 'with' (again with some exceptions) but, rather, be facilitating individuals to do it for themselves. The goal of control therefore is one in which the Learner is at the centre of all that we do and the role of Significant Others is to help the Learner to take that control. An important aspect of taking control is an understanding that the things you do have an effect on both your environment and the people within the environment: in other words 'contingency awareness'. Communication provides a means to control others.

While we may find a philosophical commitment to a particular idea or an approach fairly easy, often it is much more difficult to make that approach a reality. In observing any session involving individuals experiencing any disability one should be constantly asking 'who is in control?' If the answer to that question, for the majority of the session, is other than the Learners involved then something is amiss. In observing any sessions involving AAC Speakers look to see who is:

"Handicapped infants may begin to lose interest in a world that they do not expect to control" (Brinker & Lewis, 1982)

"Learned helplessness occurs when it is unclear to the learner that he or she is able to exert control over the environment.....For many learners, their social history has offered few opportunities to self-select desired objects, people, or activities. At meal times plates are prepared and distributed. Additional serving are provided automatically. Coats are handed out and doors opened when it is time to go. Thus, throughout the day, the caregivers do virtually everything for the learners. Initially, some learners may have attempted to self-select items of interest, but were actively encouraged not to do so." (Reichle, J. 1991 p.141)

"When children who are deafblind are young, and especially if they have additional difficulties, they may experience the world as much too large and complicated for them to exercise any control. Their experience may only be of having things done to them, not of doing things for themselves. They may have objects put in front of them to look at, but may not have any choice in the matter." (Wyman 2000 page 82)

"By providing people with PMLD the opportunities to exert control and actively participate we help to facilitate the development of contingency awareness; the knowledge that you are able to have some effect on the environment. ... If we are to prevent individuals either from resorting to self stimulatory behaviours or from withdrawing completely from the external world then it is essential that we ensure they are able to engage with their world in an active and meaningful way." (Hogg 2009. page 20)

While undoubtedly there are a plethora of goals for standard education, and many of these will have equal relevance to those experiencing a disability, there is one particular goal that Talksense believes is a vital component of any curriculum designed to prepare Individuals Experiencing any form of disability for a better quality of future life: that goal is 'control'. Communication provides an individual with a means of control.

"The provision of positive control experiences early in life will be a primary factor in helplessness immunization." (Sweeney, L. 1993)

"a high quality of life is one in which people receive individually tailored support to become full participants in the life of the community, develop skills and independence, be given appropriate choice and control over their lives, be treated with respect in a safe and secure environment”. (Emerson et al 1996)

"Empowerment occurs when control, or power, is passed to an individual or group. In rehabilitation, medicine, social work, psychology, education, and many allied disciplines, it is gradually becoming recognized that the healthiest and most effective individuals have personal control and make decisions for themselves with advice and input from others. The belief here is that, for best results overall, final decisions should be made by the individuals who are most closely affected by the decisions."

(Brown and Brown 2003 page 227)

"Students become empowered by taking control of their own learning." (Sutcliffe 1990 page 13)

"Good quality support is to do with giving people power." (Virginia Moffat 1996 page 37)

Generally speaking, the more independent people are and the less external control they receive from others, the more satisfied they are (higher quality of life) (See Legault 1992).Thus, a fundamental goal of all special education should be equipping Learners to live as independent a life as possible. This has long been recognised:

"... citizens with a mental retardation have a right to receive such individual habilitation as will give each of them a realistic opportunity to lead a more useful and meaningful life and to return to society." (Bannerman, Sheldon, Sherman, & Harchik 1990)

"even children with profound learning difficulties , given suitable conditions provided by modern technology, can make choices; in this case between sounds, voices, and rhymes provided on speakers. Moreover, they show enjoyment while so occupied and are motivated to further choice making. At the beginning of this chapter, the opinion was expressed that every step on the way to having more control over our lives is worth taking. In the case of these children, opportunity to exert control, however limited, appears to be leading to increased motivation and increasing self-regulation." (Beryl Smith 1994)(Page 5)

In order to meet this goal, staff within special education should be developing ways in which more and more control can be passed to Learners. Staff should rarely ever be doing it 'for' (there are some exceptions to this rule) and should hardly ever be doing it 'with' (again with some exceptions) but, rather, be facilitating individuals to do it for themselves. The goal of control therefore is one in which the Learner is at the centre of all that we do and the role of Significant Others is to help the Learner to take that control. An important aspect of taking control is an understanding that the things you do have an effect on both your environment and the people within the environment: in other words 'contingency awareness'. Communication provides a means to control others.

While we may find a philosophical commitment to a particular idea or an approach fairly easy, often it is much more difficult to make that approach a reality. In observing any session involving individuals experiencing any disability one should be constantly asking 'who is in control?' If the answer to that question, for the majority of the session, is other than the Learners involved then something is amiss. In observing any sessions involving AAC Speakers look to see who is:

- directing the action;

- operating any visual accompaniment (PowerPoint for example);

- activating the any switches;

- operating the augmentative / alternative communication technology;

- making choices;

- mostly in control!

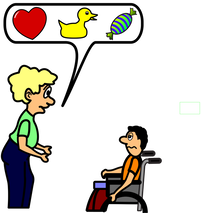

6. Sugary Speaking Surprises Series

The ‘Does He Take Sugar?’ phenomenon has occurred many times. It is truly demeaning to ignore an individual (experiencing communication difficulties) completely and address questions to others. It is a common issue (Wagner 1991; Hogg & Wilson 2004). Radio 4 used to broadcast a weekly series entitled ‘Does He Take Sugar?’ (It started in 1977 and ran for about twenty years) in which it covered the treatment of the disabled. The title of the program refers to an all-to-frequent occurrence, in which a person asks another (other than the person with the disability) a question about a topic avoiding talking to the person with the disability. People often discuss items concerning someone with a disability, while s/he is present, and do not include the person even though s/he can speak for him / herself. The radio series made this type of thing explicit and gave People Of Disability (POD) a voice.

7. Too many questions

Asking a question and then immediately asking more questions without allowing the time to respond to any of them. One morning the Carers asked me a question. By the time I had the chance to answer in sign, they had already asked several more questions. I signed "I don't know". The Carers hadn't got a clue what I was saying. They would have not known, to which of the questions they had asked, my signing was the response, because they had moved on so far beyond the original question. “Where’s it hurting?” - “Is it your leg?” - “Do you want me to get the doctor?” - “Do you want us to move you?” - “Are you feeling sick?” - “Do you feel hot?” - “What can we do to help?”

“STOP asking so many questions all at once!”

Ask only one question. Wait for a response before asking another.

“STOP asking so many questions all at once!”

Ask only one question. Wait for a response before asking another.

8. Terms of endearment

Love, Duckie, Sweetie

Love, Duckie, Sweetie

Increase in the use of ‘terms of endearment'. My Carers would often use ‘love’, ‘darling’, 'sweetheart', ‘me duck’ or some other term of endearment when addressing me until I told them to stop. I am not in a romantic relationship with any of these others, so why don't they address me by my proper name? I am old, severely disabled, and not particularly handsome. I am under no illusions that anyone would be attracted to me. There is no reason that I would warrant being addressed as 'sweetheart'. For some reason, the use of such 'terms of endearment' has increased since I became an IRON POD and needed to use AAC.

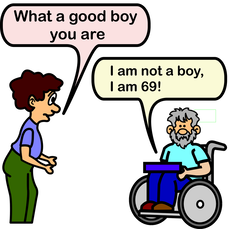

9. Inappropriate language

The use of age inappropriate language. For example, “Good boy” is not appropriate for an adult male many years your senior. When I am eating , I usually have a tea towel across my chest such that, if I accidentally drop any hot food, it falls onto the towel and not my bare flesh. Once, the Carers arrived before I started my lunch but after the towel was in place:

1st Carer: "Oh! You've got your bib on ready for dinner."

Me (struggling to speak) "Don't call it a bib. I am an adult."

2nd Carer to 1st Carer: "What did he say?"

1st Carer to 2nd Carer: " I haven’t a clue"

(and then the Carers start the normal lunch visit procedure with no attempt to ask and clarify my statement.)

1st Carer: "Oh! You've got your bib on ready for dinner."

Me (struggling to speak) "Don't call it a bib. I am an adult."

2nd Carer to 1st Carer: "What did he say?"

1st Carer to 2nd Carer: " I haven’t a clue"

(and then the Carers start the normal lunch visit procedure with no attempt to ask and clarify my statement.)

10. Choice Pickings

People think that they have the right to make decisions on my part for choices in my life. Again, taking over control and taking it away from me. You do not have the right to take control of another person just because they have an issue with communication or a learning difficulty. Ways must be found to involve the individual in her / his life choices, no matter how difficult that may be. My Carers were cleaning my bottom. I was screaming in pain. Eventually, I said, “stop please stop.” Over and over again. Did they stop? No, they continued cleaning my bottom despite my obvious distress. They took the decision to continue saying things to justify their actions, “we have got to get you clean otherwise you will be in more pain” and, “sorry just a little longer”, “nearly finished”, “almost there”, while I was begging them to stop. My decision was ignored, they took the decision for me.

"It was a common experience for people living in hospital to suffer physical and verbal abuse, be denied choices and rights, and have few educational, social or employment opportunities. Those people who lived in the community fared little better. They too had restricted choices, went to institutionalised day centres and had limited opportunities for employment and education"

(Virginia Moffat 1996 page 13)

"One of the most basic building blocks leading to enhanced self-determination is the ability to make informed choices for opportunities within one’s daily life. Considering the skills involved in becoming self-determined, choice making is one of the first and most basic skills to develop and build upon."

(Wolf, J., & Joannou, K. 2012)

The MCA (Mental Capacity Act 2005) which came into force in 2007:

"The Mental Capacity Act 2005 is the first piece of legislation to clearly state that people can no longer make decisions on behalf of others without following a process." (Fulton, Woodley, & Sanderson 2008 page 5)

Many other countries have similar legislation. This means that choice is not just a right, it is the law and we all need to understand what is considered best practice in this area.

The MCA is governed by five core principles:

"It was a common experience for people living in hospital to suffer physical and verbal abuse, be denied choices and rights, and have few educational, social or employment opportunities. Those people who lived in the community fared little better. They too had restricted choices, went to institutionalised day centres and had limited opportunities for employment and education"

(Virginia Moffat 1996 page 13)

"One of the most basic building blocks leading to enhanced self-determination is the ability to make informed choices for opportunities within one’s daily life. Considering the skills involved in becoming self-determined, choice making is one of the first and most basic skills to develop and build upon."

(Wolf, J., & Joannou, K. 2012)

The MCA (Mental Capacity Act 2005) which came into force in 2007:

"The Mental Capacity Act 2005 is the first piece of legislation to clearly state that people can no longer make decisions on behalf of others without following a process." (Fulton, Woodley, & Sanderson 2008 page 5)

Many other countries have similar legislation. This means that choice is not just a right, it is the law and we all need to understand what is considered best practice in this area.

The MCA is governed by five core principles:

- Presumption of capacity. Learners have the right to make their own decisions if they are able. Significant Others must assume that a person is able to do so unless it can be shown that the Learner is unable.

- Maximising decision making capacity. Learners should always get the necessary support to help them make their own decisions. It is important to take the necessary steps to help Learners decide for themselves before any assertion of incapacity to make a decision.

- Right to make unwise decisions. Learners have a right to make decisions others may think are not wise. Just because others may think a decision is unwise does not mean that the Learner is incapable of making a decision

- Best interests. Any act of substituted decision-making must be in the best interest of the Learner. That is, if someone other than the Learner makes a decision on his or her part, it must be in their best interest.

- Least restrictive option. Any substituted decision made should be the least restrictive option possible for the Learner.

11. Absence Phenomenon

An increase in the occurrence of the Absence Phenomenon in which people will talk together across a POD (even about the POD) as though not present. I have experienced this phenomenon myself while in hospital. Nursing staff discussing me without my involvement. I was present and absent at one and the same time! No attempt was made to include me and the nurses simply left my room without saying a word to me.

Absence Phenomenon includes but is not limited to: -

• talking between staff with no acknowledgement of the AAC Speaker;

• talking about an AAC Speaker without inclusion in the narrative;

• remaining silent and not engaging the AAC Speaker in conversation;

• treating an AAC Speaker as if s/he were not present;

• focusing on work without communicating with the AAC Speaker;

• ignoring any communication from an AAC Speaker;

• belittling / insulting an AAC Speaker while they are present;

• "does s/he take sugar?" attitude, where the AAC Speaker is overlooked in favour of the support worker;

• focusing on anything but the message from the AAC Speaker. Complaining about the quality of the voice,

for example, or focusing on the grammar rather than the communication.

I recently received a message from Megan, who said,

"I live in a ventilator hospital. I cannot speak. It's amazing the things. staff will talk about in front of me like I'm not there. Not only about me , but their personal lives, issues they have with other staff, new hospital policies, etc. I could write a book."

Absence Phenomenon includes but is not limited to: -

• talking between staff with no acknowledgement of the AAC Speaker;

• talking about an AAC Speaker without inclusion in the narrative;

• remaining silent and not engaging the AAC Speaker in conversation;

• treating an AAC Speaker as if s/he were not present;

• focusing on work without communicating with the AAC Speaker;

• ignoring any communication from an AAC Speaker;

• belittling / insulting an AAC Speaker while they are present;

• "does s/he take sugar?" attitude, where the AAC Speaker is overlooked in favour of the support worker;

• focusing on anything but the message from the AAC Speaker. Complaining about the quality of the voice,

for example, or focusing on the grammar rather than the communication.

I recently received a message from Megan, who said,

"I live in a ventilator hospital. I cannot speak. It's amazing the things. staff will talk about in front of me like I'm not there. Not only about me , but their personal lives, issues they have with other staff, new hospital policies, etc. I could write a book."

12. RSVP

Not giving an AAC Speaker enough time to respond to a question asked (or take a turn in the communication) before answering it yourself. Perhaps, asking another further question or just continuing chatting. The conversation (if you can call it that!), therefore, is primarily one-sided. The communication partner is active and dominant and the AAC Speaker is passive and submissive.

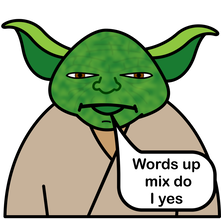

13. Grammar rules OK?

The focus is other than the content of the AAC Speaker's message. Iwas once in a school talking with a senior member of the staff when a pupil (an AAC Speaker) approached. He said carefully and slowly, word by word, "greenhouse go now want please". His message was obvious and clear but, instead of responding to fantastic use of an AAC system, the staff member said, "when you can say it properly, I will allow you to go. It's 'Please may I go to the greenhouse sir?' ". I was appalled but I failed to chastise that senior staff member. In hindsight, I was in the wrong too; I should have spoken up on behalf of the AAC Speaker but, I was younger and inexperienced. No excuse!

14. Cannot Cope with Clarifying Communication

Some people are too embarrassed to ask an AAC Speaker for clarification of her / his message if its meaning wasn't clear. They will just act upon their assumed understanding of what was said. If you're unsure of an AAC Speaker's meaning, it is alright to say, "sorry, I was confused by what you just said. Can you say it another way?" or, "sorry, I'm stupid, I don't understand what you mean".

15. Passivity

Passivity is commonplace amongst people with a severe communication impairment. In a study by Sweeney (SWEENEY L. 1991) 42 out of 50 AAC Speakers showed some level of learned helplessness when interacting with one or more significant others. The more severe the communication impairment the greater the degree of helplessness. It would appear that, the development of an individual’s ability to communicate also effects an improvement in an individual’s desire to act independently. The factors that are involved in creating an atmosphere that is supportive of communication are also the factors that tend to demand more interactive skills of an individual. The relationship is reciprocal: greater communicative ability may lead to greater independence and greater independence may lead to greater communicative ability. However, prevention is better than cure: the role of communication in the avoidance of personal passivity should be stressed:

"Without an effective means of communication during childhood development of autonomy, exploratory / experiential opportunity, and relative strength of self-image/esteem will be compromised." (SWEENEY L. 1993)

However well written, structured, or sound a programme of work and study may be, without the right attitude of the people who have to implement the strategies developed, it will be doomed to failure. It is one of the facilitator’s primary roles to ensure the correct attitude and understanding of all significant others. It is the attitudes, knowledge, understanding, and abilities of significant others that will contribute most to the success (or failure) of the cognitive and linguistic development of the user. Candappa and Burgess (1989) have shown how the perceptions and attitudes of significant others play a primary role in the normalisation of people with a cognitive impairment. They argue:

"Our own study, ... strongly suggests that addressing the values and perceptions of carers is one of the primary tasks of normalisation." (CANDAPPA M. & BURGESS R. 1989)

This is supported by SWEENEY (1993):

"All children are dependent upon adult caretakers for fulfilment of their physical and emotional needs. In the process of becoming autonomous, children explore and test their world and begin signalling their growing independence to caretakers through physical actions and spoken messages. If provided with an adequate climate for growth, an increasingly solid foundation for independence in adult life will be formed. However, for children with severe communication and/or physical limitations this process of self growth may be overlooked or suppressed. Because many children experiencing the aforementioned challenges are not able to signal their readiness for exploration or independence in traditional ways, parents and other caretakers (e.g. professional service providers, educators, etc.) are inclined to continue to act as direct or indirect agents for fulfilling the child’s needs. When later provided with adequate means to express, query, or explore, (e.g. assistive technology) the child may persist in a more passive state due to learned helplessness or learned dependency."

For communication users to be successful, they have to have a desire to communicate. The very institutionalisation of some settings may, however, reinforce user passivity. Only when there is a change in institutional practices, reflected through the attitudes of the staff, will any progress be made. A person for whom all needs are provided (according to a timetable) will find it difficult to put communication to positive use. It may only be through the creation of anomaly, of discord in the daily routine, that the need for communication is created. The normalisation principle may provide just such anomaly and discord creating the desire to communicate in some users (or, at least, allowing those with the responsibility for this process to see the urgency for the development of communication skills).

"...but to consider the part played by speech in all this. The more a learner controls his own language strategies, and the more he is enabled to think aloud, the more he can take responsibility for formulating explanatory hypotheses and evaluating them. It is not easy to make this possible in a typical lesson: my contention at this point is that ... pupils ... are capable of this if they are placed in a social context which supports it." (BARNES D. 1976)

Change is not easy. However, it will be made more difficult if the primary facilitator lacks belief in the potential of the user, the staff, the system and perhaps, most importantly, belief in his or herself (See SELIGMAN M. 1992). A positive outgoing character, committed to alternative communication and the benefits it can bring, may be more important than the quality of the system being used. Sheer guts and determination coupled with a weaker system will triumph over the best system coupled with indolence and apathy.

"... many adult AAC users may unconsciously choose to be passive." (MERCHEN M. 1990)

"Many users of augmentative communicative systems have learned to refrain from independently engaging in regular daily activities because they have received assistance in virtually every aspect of their life." (REICHLE J. 1991 p. 151) (See also SELIGMAN M. 1975; GUESS D., BENSON H., & SIEGEL-CAUSEY E., 1985)

"For children who grow up with motor disorders, the difficulties they experience in moving and speaking and the influence from their environment both contribute to the development of a passive style. These children often place great demands on their parents. Training, feeding and washing take up a lot of time, and there are few activities that the children and their parents can take part in together. Even when the children are small, their parents consider them to be happiest when they are passive. "She’s as quiet as an angel”, and, "She is so good”, are typical remarks made by mothers about their small children with cerebral palsy."

(VON TETZCHNER S. & MARTINSEN H. 1992) (See also SHERE B. & KASTENBAUM R. 1966)

The cartoon makes the point that passive children grow into passive adults. There are many reasons for doing things for children who are capable of doing them for themselves:

- guilt;

- lack of time;

- wanting to help;

- a belief that a disability equates with inability.

There are also many reasons for the growth of passivity:

- failure to see the long-term consequences of short-term actions (What does it matter if I help a little?);

- the use of closed rather than open questions;

- failure to involve;

- lack of options;

- lack of choice;

- immobility;

- failure to present experience of the world;

- failure to realise that whole sections of standard patterns of language acquisition are being missed;

- failure to check on conceptual development.

"Without an effective means of communication during childhood development of autonomy, exploratory / experiential opportunity, and relative strength of self-image/esteem will be compromised." (SWEENEY L. 1993)

However well written, structured, or sound a programme of work and study may be, without the right attitude of the people who have to implement the strategies developed, it will be doomed to failure. It is one of the facilitator’s primary roles to ensure the correct attitude and understanding of all significant others. It is the attitudes, knowledge, understanding, and abilities of significant others that will contribute most to the success (or failure) of the cognitive and linguistic development of the user. Candappa and Burgess (1989) have shown how the perceptions and attitudes of significant others play a primary role in the normalisation of people with a cognitive impairment. They argue:

"Our own study, ... strongly suggests that addressing the values and perceptions of carers is one of the primary tasks of normalisation." (CANDAPPA M. & BURGESS R. 1989)

This is supported by SWEENEY (1993):

"All children are dependent upon adult caretakers for fulfilment of their physical and emotional needs. In the process of becoming autonomous, children explore and test their world and begin signalling their growing independence to caretakers through physical actions and spoken messages. If provided with an adequate climate for growth, an increasingly solid foundation for independence in adult life will be formed. However, for children with severe communication and/or physical limitations this process of self growth may be overlooked or suppressed. Because many children experiencing the aforementioned challenges are not able to signal their readiness for exploration or independence in traditional ways, parents and other caretakers (e.g. professional service providers, educators, etc.) are inclined to continue to act as direct or indirect agents for fulfilling the child’s needs. When later provided with adequate means to express, query, or explore, (e.g. assistive technology) the child may persist in a more passive state due to learned helplessness or learned dependency."

For communication users to be successful, they have to have a desire to communicate. The very institutionalisation of some settings may, however, reinforce user passivity. Only when there is a change in institutional practices, reflected through the attitudes of the staff, will any progress be made. A person for whom all needs are provided (according to a timetable) will find it difficult to put communication to positive use. It may only be through the creation of anomaly, of discord in the daily routine, that the need for communication is created. The normalisation principle may provide just such anomaly and discord creating the desire to communicate in some users (or, at least, allowing those with the responsibility for this process to see the urgency for the development of communication skills).

"...but to consider the part played by speech in all this. The more a learner controls his own language strategies, and the more he is enabled to think aloud, the more he can take responsibility for formulating explanatory hypotheses and evaluating them. It is not easy to make this possible in a typical lesson: my contention at this point is that ... pupils ... are capable of this if they are placed in a social context which supports it." (BARNES D. 1976)

Change is not easy. However, it will be made more difficult if the primary facilitator lacks belief in the potential of the user, the staff, the system and perhaps, most importantly, belief in his or herself (See SELIGMAN M. 1992). A positive outgoing character, committed to alternative communication and the benefits it can bring, may be more important than the quality of the system being used. Sheer guts and determination coupled with a weaker system will triumph over the best system coupled with indolence and apathy.

"... many adult AAC users may unconsciously choose to be passive." (MERCHEN M. 1990)

"Many users of augmentative communicative systems have learned to refrain from independently engaging in regular daily activities because they have received assistance in virtually every aspect of their life." (REICHLE J. 1991 p. 151) (See also SELIGMAN M. 1975; GUESS D., BENSON H., & SIEGEL-CAUSEY E., 1985)

"For children who grow up with motor disorders, the difficulties they experience in moving and speaking and the influence from their environment both contribute to the development of a passive style. These children often place great demands on their parents. Training, feeding and washing take up a lot of time, and there are few activities that the children and their parents can take part in together. Even when the children are small, their parents consider them to be happiest when they are passive. "She’s as quiet as an angel”, and, "She is so good”, are typical remarks made by mothers about their small children with cerebral palsy."

(VON TETZCHNER S. & MARTINSEN H. 1992) (See also SHERE B. & KASTENBAUM R. 1966)

The cartoon makes the point that passive children grow into passive adults. There are many reasons for doing things for children who are capable of doing them for themselves:

- guilt;

- lack of time;

- wanting to help;

- a belief that a disability equates with inability.

There are also many reasons for the growth of passivity:

- failure to see the long-term consequences of short-term actions (What does it matter if I help a little?);

- the use of closed rather than open questions;

- failure to involve;

- lack of options;

- lack of choice;

- immobility;

- failure to present experience of the world;

- failure to realise that whole sections of standard patterns of language acquisition are being missed;

- failure to check on conceptual development.

16. SHACKLE

"There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is being talked for." (JONES A.P. 1994 with apologies to OSCAR WILDE!)

Surrogate Human Augmentative Communicator - Keeping Learners Enslaved

The cartoon makes the point that it is possible to increase passivity by continuing to talk for a person long past the time when this ceases to be necessary:

"We would not, for example, expect a normally developing two year old to accurately report detailed symptomatology of an illness to their paediatrician. However, when surrogate communicating and other cultivators of dependency extend beyond the time of relevant need, learned helpless may result."

(SWEENEY L. 1993)

"The view of oneself as dependent, even as ‘helpless’ can be hard for many children to shake off. Those with a communication problem may be even more entrenched in patterns of looking to others to speak for them, decide for them and of setting up their parents, siblings and friends as more competent and more responsible than themselves. In some ways it makes for an easier life. It also detracts from the child’s potential. Because of a communication problem a child may hang back from many everyday interactions and lack not only the skills but the experience of fending for themselves. If mother has always asked for things in shops or answered the telephone or spoken for the child to teachers, family members and strangers, the child will not know how to begin." (DALTON P. 1994, page 133)

A surrogate communicator is defined as:

"An individual who assumes one or more communicative roles or provides one or more communication functions for another person regardless of the necessity to do so." (SWEENEY L. 1991)

This is not likely to be a deliberate act of malice by the surrogate communicator but occurs for a number of other reasons:

- habit;

- care;

- a desire for success;

- embarrassment;

- impatience;

- failure to perceive potential;

- an assumption that the listener will not understand.

The shackle, in this case, has the long-term effect of promoting or maintaining passivity or both in an otherwise active person. We must not be tempted to answer for a person unless that person has given permission. There is a danger. A passive person may continually give permission for someone else to answer. In this instance, it is better the user initiates the request on each occasion. This may be a subtle signal between the augmented communicator and the person being asked to respond. Yet again, there are problems. First, a subtle signal may not be obvious to the listener. The listener may learn to answer on behalf of an augmented communicator without being given permission. Second, a passive person may learn to give the signal for another person to communicate on her or his behalf and never attempt to communicate for her or himself.

"It is not uncommon for children with delayed language development to ask their parents to speak for them when strangers approach them, even after their speech is understood by others."

(VON TETZCHNER S. & MARTINSEN H. 1992)

Being aware of the pitfalls may help in avoiding these sorts of problems before they arise.

Surrogate Human Augmentative Communicator - Keeping Learners Enslaved

The cartoon makes the point that it is possible to increase passivity by continuing to talk for a person long past the time when this ceases to be necessary:

"We would not, for example, expect a normally developing two year old to accurately report detailed symptomatology of an illness to their paediatrician. However, when surrogate communicating and other cultivators of dependency extend beyond the time of relevant need, learned helpless may result."

(SWEENEY L. 1993)

"The view of oneself as dependent, even as ‘helpless’ can be hard for many children to shake off. Those with a communication problem may be even more entrenched in patterns of looking to others to speak for them, decide for them and of setting up their parents, siblings and friends as more competent and more responsible than themselves. In some ways it makes for an easier life. It also detracts from the child’s potential. Because of a communication problem a child may hang back from many everyday interactions and lack not only the skills but the experience of fending for themselves. If mother has always asked for things in shops or answered the telephone or spoken for the child to teachers, family members and strangers, the child will not know how to begin." (DALTON P. 1994, page 133)

A surrogate communicator is defined as:

"An individual who assumes one or more communicative roles or provides one or more communication functions for another person regardless of the necessity to do so." (SWEENEY L. 1991)

This is not likely to be a deliberate act of malice by the surrogate communicator but occurs for a number of other reasons:

- habit;

- care;

- a desire for success;

- embarrassment;

- impatience;

- failure to perceive potential;

- an assumption that the listener will not understand.

The shackle, in this case, has the long-term effect of promoting or maintaining passivity or both in an otherwise active person. We must not be tempted to answer for a person unless that person has given permission. There is a danger. A passive person may continually give permission for someone else to answer. In this instance, it is better the user initiates the request on each occasion. This may be a subtle signal between the augmented communicator and the person being asked to respond. Yet again, there are problems. First, a subtle signal may not be obvious to the listener. The listener may learn to answer on behalf of an augmented communicator without being given permission. Second, a passive person may learn to give the signal for another person to communicate on her or his behalf and never attempt to communicate for her or himself.

"It is not uncommon for children with delayed language development to ask their parents to speak for them when strangers approach them, even after their speech is understood by others."

(VON TETZCHNER S. & MARTINSEN H. 1992)

Being aware of the pitfalls may help in avoiding these sorts of problems before they arise.

17. I hear that...

Assumptions that an AAC Speaker must be hard of hearing. People often raise the level of their voice although my auditory acuity is very good. It is good practice to speak in normal tones; the individual will always let you know if you need to speak up.

18. Shortening Dread

There is a tendency to avoid conversations with people whom we: -

• don't like;

• find embarrassing;

• feel make us awkward;

• don't understand;

• find tedious;

• think speak too slowly;

• believe will take too much of our time;

• xxx.

For whatever reason, an AAC Speaker might be seen to fall into one or more of the above criteria. As such, potential communication partners might actively avoid any interactions with the AAC Speaker. This may lead to the Potential Communication Partner (PCP): -

• keeping conversations short;

• failing to use language that would encourage an extension of the conversation;

• taking control / dominating the interchange;

• xxx

with a potential of the AAC Speaker: -

• lacking in real-time use of the AAC system;

• not retaining vocabulary;

• having problematic pragmatic abilities;

• undervaluing the AAC system;

• failing to use the AAC system;

• rejecting the AAC system;

• becoming socially isolated;

• increasing in behaviour that others might find challenging.

• don't like;

• find embarrassing;

• feel make us awkward;

• don't understand;

• find tedious;

• think speak too slowly;

• believe will take too much of our time;

• xxx.

For whatever reason, an AAC Speaker might be seen to fall into one or more of the above criteria. As such, potential communication partners might actively avoid any interactions with the AAC Speaker. This may lead to the Potential Communication Partner (PCP): -

• keeping conversations short;

• failing to use language that would encourage an extension of the conversation;

• taking control / dominating the interchange;

• xxx

with a potential of the AAC Speaker: -

• lacking in real-time use of the AAC system;

• not retaining vocabulary;

• having problematic pragmatic abilities;

• undervaluing the AAC system;

• failing to use the AAC system;

• rejecting the AAC system;

• becoming socially isolated;

• increasing in behaviour that others might find challenging.

19. Baby Talk

What is age appropriate language?

Age-appropriate language. This means:

• using language that can be understood by the person with whom you are communicating;

• not using language that is inappropriate for the individual with whom you are communicating, neither too old nor too young.

While you should not utilise the vernacular / idioms of the person with whom you are speaking, you sould speak using a level of language that is appropriate for their age and level of cognition.

Are there components of appropriate language?

The 5 domains of language include: phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics.

Age-appropriate language. This means:

• using language that can be understood by the person with whom you are communicating;

• not using language that is inappropriate for the individual with whom you are communicating, neither too old nor too young.

While you should not utilise the vernacular / idioms of the person with whom you are speaking, you sould speak using a level of language that is appropriate for their age and level of cognition.

Are there components of appropriate language?

The 5 domains of language include: phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics.

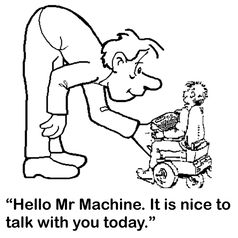

20. Machine Mistakes

I have been told by long time AAC Speakers that occasionally they encounter a person who will talk to the communication device rather than them. As though the device was sentient. While AI is progressing with each passing year, we are not yet at the time of AAC system sentience! Although, I am sure that day will come.

Bibliography and References

The following list does not claim to be comprehensive on the topic area.

If you feel that a particular reference is missing, please get in touch using the form provided at the foot of this page.

Bannerman, D.J., Sheldon, J.B., Sherman, J.A., & Harchik, A.E., (1990). Balancing the right to habilitation with the right to personal liberties: The rights of people with developmental disabilities to eat too many doughnuts and take a nap. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, Volume 23; pp. 79 - 89.

Barnes, D., (1966). Presentation at an Anglo-American conference on English teaching in 1966 at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire

Quoted in - Growth through English. Dixon, J., Oxford University Press, 1969.

Barnes, D., Britton, J., & Rosen, H., (1971). Language, the learner and the school. Penguin. Revised edition

Barnes, D., (1976). From Communication to Curriculum. Penguin

Bigby, C., Clement, T., Mansell, J. & Beadle‐Brown, J., (2009). ‘It's pretty hard with our ones, they can't talk, the more able bodied can participate’: Staff attitudes about the applicability of disability policies to people with severe and profound intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, Volume 53(4), pp.363 - 376.

Brinker, R.P., & Lewis, M.L., (1982). Discovering the competent handicapped infant: a process approach to assessment and intervention.Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, Volume 2, pp. 1 - 16.

Brown, I., & Brown, R.I., (2003). Quality of Life and Disability. Jessica Kingsley.

Candappa, M., & Burgess, R., (1989) . I’m not handicapped ‑ I’m Different: ‘Normalisation’, hospital care, and mental handicap.

In ‑ Disability and dependency. Barton, L. (Ed.) Falmer Press

Dalton, P., (1988). Personal Construct psychology and speech therapy in Britain. A time of transition. Clinical Uses of Personal Construct Psychology. London: Routledge & Kegan.

Dalton, P., (1994). Counselling people with communication problems. London: Sage Publications. ISBN 0-8039-8895-8

Emerson, E., Cullen, C., Hatton, C., & Cross, B., (1996). Residential Provision for People with Learning Disabilities: Summary Report. Manchester: Hester Adrian Research Centre, Manchester University.

Fried-Oken, M., Beukelman, D.R., and Hux, K., (2012). Current and future AAC research considerations for adults with acquired cognitive and communication impairments. Assistive Technology, Volume 24(1), pp. 56 - 66.

Fulton, K., Woodley, K., & Sanderson, H., (2008). Supported Decision Making: A guide for supporters, Paradigm

Hagstrom, F., (2004). Expanding Consideration of the Personal When Considering AAC. Perspectives on Gerontology,

Volume 9(2), pp.13 - 16.

Hogg, G., & Wilson, E., (2004). Does he take sugar? The disabled consumer and identity. In British Academy of Management Conference Proceedings. St. Andrews, Scotland.

Hog, R., (2009). Using switch-technology to facilitate the development of contingency-awareness in people with PMLD, PMLD Link, Volume 21, No. 2, Issue 63.

García Iriarte, E., O'Brien, P., McConkey, R., Wolfe, M., & O'Doherty, S., (2014). Identifying the Key Concerns of Irish Persons with Intellectual Disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, Volume 27(6), pp.564 - 575.

Guess, D., Benson, H., & Siegel-Causey, E., (1985). Concepts and issues related to choice making and autonomy among persons with severe disabilities. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, Volume 10, (2), pp. 79 - 86.

Jeffree, D., & McConkey, R., (1976). Let me speak. London: Human Horizons Series: Souvenir Press

Jones, A.P., (1996). Impact. Liberator Ltd. Swinstead, Lincolnshire.

Legault, J.R., (1992). A study of the relationship of community living situation to independence and satisfaction on the lives of mentally retarded adults. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. Volume 36: pp. 129 - 141.

Merchen, M.A., (1984). Technology and people. Communication Outlook. Volume 6, Number 2, pp. 12 - 13.

Merchen, M.A., (1985a). A lucky accident: I discover a better handpiece. Communication Outlook. Volume 6 (4), pp. 6 - 8.

Merchen, M.A., (1985b). Writing is a big help. Communication Outlook. Volume 6, (4), page 2.

Merchen, M.A., (1985c). Some thoughts concerning communication and individuals experiencing handicaps. Communication Outlook,

Volume 7, (2), Fall 1985, pp. 11 - 12.

Merchen, M.A., (1986). Enabling more people to take advantage of the computer age. Communication Outlook. Volume 7, (4), pp. 13.

Merchen, M.A., (1987). Blowing off steam in hopes of being of a little assistance. Communicating Together. Volume 5, Number 2, page 11.

Merchen, M.A., (1989). A bittersweet experience. The ISAAC Bulletin. Number 19, November 1989, page 22.

Merchen, M.A., (1990). Some reasons for being passive from a personal perspective. Communication Outlook, Volume 12, (1), pp. 10 - 11.

Moffat, V., (1996). Life Without Jargon: How to Help People with Learning Difficulties Understand What You Are Saying. Choice Press.

Reichle, J., (1991). Developing communicative exchanges, In - Implementing Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Strategies for Learners with Severe Disabilities, pp. 133 - 156, Reichle, J., York, J., & Sigafoos, J. (Eds.). Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Ryan, S., (2005). ‘People don't do odd, do they?’Mothers making sense of the reactions of others towards their learning disabled children in public places. Children's Geographies, Volume 3(3), pp.291 - 305.

Seligman, M.,(1984). Helplessness: On depression, development and death. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

Seligman, M., (1992). Learned Optimism. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Shere, B., & Kastenbaum, R., (1966). Mother child interaction in cerebral palsy: Environment and psychosocial obstacles to cognitive development. Genetic Psychology Monographs. Volume 73, pp. 255 - 335.

Smith, B., (1994). Handing over control to people with learning difficulties. In J. Coupe-O'Kane and B. Smith - Taking Control: Enabling people with learning difficulties. David Fulton Publishers.

Smith, B., (1996). Discussion: Age-appropriate or Developmentally appropriate Activities? In - Coupe O’Kane, J. & Goldbart, J. (eds)

Whose Choice? - Contentious Issues For Those Working With People With Learning Difficulties. London: David Fulton.

Sutcliffe, J., (1990). Adults with learning difficulties: Education for choice and empowerment. National Institute for Adult Continuing Education (NIACE) in association with the Open University Press.

Sweeney, L.A., (1991). Learned dependency and co-dependency among potential users of augmentative communication.

American Speech Language Hearing Association, Miniseminar, Atlanta, Georgia.

Sweeney, L.A., (1993). Helplessness, dependency, an explanatory style as variables of employment potential among Augmented Communicators. First Annual Pittsburgh Employment Conference for Augmented Communicators Proceedings. August 20-22: Shout Press: Pittsburgh.

Therrien, M.C., (2019). Perspectives and experiences of adults who use AAC on making and keeping friends. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 35(3), pp. 205 - 216.

Von Tetzchner, S., & Martinsen, H., (1992a). Introduction to Sign Teaching and the Use of Communication Aids. Whurr Publishers.

ISBN 1-870332-28-8

Von Tetzchner, S., & Martinsen, H., (1992b). Introduction to symbolic and augmentative communication. San Diego: CA: Singular Publishing.

Wagner, M.G., (1991). Does he take sugar? World health forum; Volume 12(1) : pp, 87 - 89 https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/49206

Wilson‐Kovacs, D., Ryan, M.K., Haslam, S.A., & Rabinovich, A., (2008). ‘Just because you can get a wheelchair in the building doesn't necessarily mean that you can still participate’: barriers to the career advancement of disabled professionals. Disability & Society, Volume 23(7), pp.705 - 717.

Wyman, R., (2000). Making Sense Together: Practical approaches to supporting children who have multisensory impairments. Human Horizons Series, Souvenir Press

Barnes, D., (1966). Presentation at an Anglo-American conference on English teaching in 1966 at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire

Quoted in - Growth through English. Dixon, J., Oxford University Press, 1969.

Barnes, D., Britton, J., & Rosen, H., (1971). Language, the learner and the school. Penguin. Revised edition

Barnes, D., (1976). From Communication to Curriculum. Penguin

Bigby, C., Clement, T., Mansell, J. & Beadle‐Brown, J., (2009). ‘It's pretty hard with our ones, they can't talk, the more able bodied can participate’: Staff attitudes about the applicability of disability policies to people with severe and profound intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, Volume 53(4), pp.363 - 376.

Brinker, R.P., & Lewis, M.L., (1982). Discovering the competent handicapped infant: a process approach to assessment and intervention.Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, Volume 2, pp. 1 - 16.

Brown, I., & Brown, R.I., (2003). Quality of Life and Disability. Jessica Kingsley.

Candappa, M., & Burgess, R., (1989) . I’m not handicapped ‑ I’m Different: ‘Normalisation’, hospital care, and mental handicap.

In ‑ Disability and dependency. Barton, L. (Ed.) Falmer Press

Dalton, P., (1988). Personal Construct psychology and speech therapy in Britain. A time of transition. Clinical Uses of Personal Construct Psychology. London: Routledge & Kegan.

Dalton, P., (1994). Counselling people with communication problems. London: Sage Publications. ISBN 0-8039-8895-8

Emerson, E., Cullen, C., Hatton, C., & Cross, B., (1996). Residential Provision for People with Learning Disabilities: Summary Report. Manchester: Hester Adrian Research Centre, Manchester University.

Fried-Oken, M., Beukelman, D.R., and Hux, K., (2012). Current and future AAC research considerations for adults with acquired cognitive and communication impairments. Assistive Technology, Volume 24(1), pp. 56 - 66.

Fulton, K., Woodley, K., & Sanderson, H., (2008). Supported Decision Making: A guide for supporters, Paradigm

Hagstrom, F., (2004). Expanding Consideration of the Personal When Considering AAC. Perspectives on Gerontology,

Volume 9(2), pp.13 - 16.

Hogg, G., & Wilson, E., (2004). Does he take sugar? The disabled consumer and identity. In British Academy of Management Conference Proceedings. St. Andrews, Scotland.

Hog, R., (2009). Using switch-technology to facilitate the development of contingency-awareness in people with PMLD, PMLD Link, Volume 21, No. 2, Issue 63.

García Iriarte, E., O'Brien, P., McConkey, R., Wolfe, M., & O'Doherty, S., (2014). Identifying the Key Concerns of Irish Persons with Intellectual Disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, Volume 27(6), pp.564 - 575.

Guess, D., Benson, H., & Siegel-Causey, E., (1985). Concepts and issues related to choice making and autonomy among persons with severe disabilities. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, Volume 10, (2), pp. 79 - 86.

Jeffree, D., & McConkey, R., (1976). Let me speak. London: Human Horizons Series: Souvenir Press

Jones, A.P., (1996). Impact. Liberator Ltd. Swinstead, Lincolnshire.

Legault, J.R., (1992). A study of the relationship of community living situation to independence and satisfaction on the lives of mentally retarded adults. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. Volume 36: pp. 129 - 141.

Merchen, M.A., (1984). Technology and people. Communication Outlook. Volume 6, Number 2, pp. 12 - 13.

Merchen, M.A., (1985a). A lucky accident: I discover a better handpiece. Communication Outlook. Volume 6 (4), pp. 6 - 8.

Merchen, M.A., (1985b). Writing is a big help. Communication Outlook. Volume 6, (4), page 2.

Merchen, M.A., (1985c). Some thoughts concerning communication and individuals experiencing handicaps. Communication Outlook,

Volume 7, (2), Fall 1985, pp. 11 - 12.

Merchen, M.A., (1986). Enabling more people to take advantage of the computer age. Communication Outlook. Volume 7, (4), pp. 13.

Merchen, M.A., (1987). Blowing off steam in hopes of being of a little assistance. Communicating Together. Volume 5, Number 2, page 11.

Merchen, M.A., (1989). A bittersweet experience. The ISAAC Bulletin. Number 19, November 1989, page 22.

Merchen, M.A., (1990). Some reasons for being passive from a personal perspective. Communication Outlook, Volume 12, (1), pp. 10 - 11.

Moffat, V., (1996). Life Without Jargon: How to Help People with Learning Difficulties Understand What You Are Saying. Choice Press.

Reichle, J., (1991). Developing communicative exchanges, In - Implementing Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Strategies for Learners with Severe Disabilities, pp. 133 - 156, Reichle, J., York, J., & Sigafoos, J. (Eds.). Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Ryan, S., (2005). ‘People don't do odd, do they?’Mothers making sense of the reactions of others towards their learning disabled children in public places. Children's Geographies, Volume 3(3), pp.291 - 305.

Seligman, M.,(1984). Helplessness: On depression, development and death. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

Seligman, M., (1992). Learned Optimism. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Shere, B., & Kastenbaum, R., (1966). Mother child interaction in cerebral palsy: Environment and psychosocial obstacles to cognitive development. Genetic Psychology Monographs. Volume 73, pp. 255 - 335.

Smith, B., (1994). Handing over control to people with learning difficulties. In J. Coupe-O'Kane and B. Smith - Taking Control: Enabling people with learning difficulties. David Fulton Publishers.

Smith, B., (1996). Discussion: Age-appropriate or Developmentally appropriate Activities? In - Coupe O’Kane, J. & Goldbart, J. (eds)

Whose Choice? - Contentious Issues For Those Working With People With Learning Difficulties. London: David Fulton.

Sutcliffe, J., (1990). Adults with learning difficulties: Education for choice and empowerment. National Institute for Adult Continuing Education (NIACE) in association with the Open University Press.

Sweeney, L.A., (1991). Learned dependency and co-dependency among potential users of augmentative communication.

American Speech Language Hearing Association, Miniseminar, Atlanta, Georgia.

Sweeney, L.A., (1993). Helplessness, dependency, an explanatory style as variables of employment potential among Augmented Communicators. First Annual Pittsburgh Employment Conference for Augmented Communicators Proceedings. August 20-22: Shout Press: Pittsburgh.

Therrien, M.C., (2019). Perspectives and experiences of adults who use AAC on making and keeping friends. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Volume 35(3), pp. 205 - 216.

Von Tetzchner, S., & Martinsen, H., (1992a). Introduction to Sign Teaching and the Use of Communication Aids. Whurr Publishers.

ISBN 1-870332-28-8

Von Tetzchner, S., & Martinsen, H., (1992b). Introduction to symbolic and augmentative communication. San Diego: CA: Singular Publishing.

Wagner, M.G., (1991). Does he take sugar? World health forum; Volume 12(1) : pp, 87 - 89 https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/49206

Wilson‐Kovacs, D., Ryan, M.K., Haslam, S.A., & Rabinovich, A., (2008). ‘Just because you can get a wheelchair in the building doesn't necessarily mean that you can still participate’: barriers to the career advancement of disabled professionals. Disability & Society, Volume 23(7), pp.705 - 717.

Wyman, R., (2000). Making Sense Together: Practical approaches to supporting children who have multisensory impairments. Human Horizons Series, Souvenir Press

Enquiry form

Please use this form to: -

• make contact;

• comment on this page;

• request cartoons, images, symbols.

• make enquiries.

Navigation

Return to the top of the page.